FIRST CENTURY AVANT-GARDE FILM RUTH NOVACZEK a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Proquest Dissertations

AFTERIMAGES AND AFTERTHOUGHTS ABOUT THE AFTERLIFE OF FILM A MEMORY OF RESISTANCE Gerda Johanna Cammaer A Research-Creation Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2009 © Gerda Johanna Cammaer, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-67380-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-67380-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Full Program (Pdf)

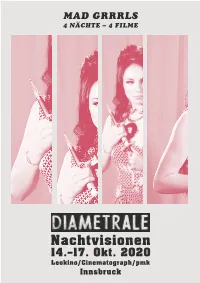

MAD GRRRLS 4 NÄCHTE – 4 FILME Nachtvisionen 14.–17. Okt. 2020 Leokino/Cinematograph/pmk Innsbruck 2. DIAMETRALE Nachtvisionen 14. – 17. Oktober 2020 im Leokino/Cinematograph/p.m.k MAD GRRRLS – transgressiv, transaggressiv, transfantastisch! Die Nachtvisionen beleben die Tradition der Spätvorstellungen in Innsbruck wieder – und bringen damit die dazugehörenden Genrefilme ins Leokino! Ob Klassiker oder moderne Produktionen, die nächtlichen Visionen widmen sich transgressiven Nischen- kategorien: B-Movies, Undergroundfilme, Exploitation-, Trash-, Genrekino... Kurz gesagt alles, was damals noch mit einem X versehen war, heute in der Kultfilmlade schlummert und nur darauf wartet, euch nächtens zu berauschen. Das diesjährige Programm der Nachtvisionen nimmt starke, selbst- bewusste Frauen in den Fokus. Unter dem Motto MAD GRRRLS wird Frauen- und Freiheitskampf verhandelt, feministischer Lust- mord und fetischisierte Rachlust thematisiert und Hedonismus und weibliche Selbstbestimmtheit gefeiert. Die Zusammenstellung von 2 Klassikern und 2 Neuproduktionen, jeweils von 2 Regisseurinnen und von 2 Regisseuren, ermöglicht nicht nur interessante, filmge- schichtliche Vergleiche, sondern befeuert die vielfältige Imagination von starken Frauen. Wir wünschen schrillfeministische und transfantastische Kinonächte! Verein zur Förderung experimenteller und komischer FilmKunst 3 Informationen Tickets Einzeltickets Kino 9,50 EUR ermäßigt 7,90 EUR*) *) Studierende und alle unter 25. Do 15.10. p.m.k 7,00 EUR –Einzeltickets für die Filme sind an der Kasse im Leokino und Cinematograph erhältlich. –Tickets für die Veranstaltung in der p.m.k sind nur an der Abendkasse erhältlich. COVID-19 Alle Veranstaltungen finden unter Berück- sichtigung der geltenden COVID-19-Verord- nung statt. Infos: www.diametrale.at/tickets Reservierung Leokino/Cinematograph Tel. +43 512 560470/-50 oder ein charmantes Mail an [email protected] Karten müssen 15 Minuten vor den Screenings abgeholt werden. -

Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic

SOFIA COPPOLA AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AN APPEALING AESTHETIC by LEILA OZERAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Leila Ozeran for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2016 Title: Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic Approved: r--~ ~ Professor Priscilla Pena Ovalle This thesis grew out of an interest in the films of female directors, producers, and writers and the substantially lower opportunities for such filmmakers in Hollywood and Independent film. The particular look and atmosphere which Sofia Coppola is able to compose in her five films is a point of interest and a viable course of study. This project uses her fifth and latest film, Bling Ring (2013), to showcase Coppola's merits as a filmmaker at the intersection of box office and critical appeal. I first describe the current filmmaking landscape in terms of gender. Using studies by Dr. Martha Lauzen from San Diego State University and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to illustrate the statistical lack of a female presence in creative film roles and also why it is important to have women represented in above-the-line positions. Then I used close readings of Bling Ring to analyze formal aspects of Sofia Coppola's filmmaking style namely her use of distinct color palettes, provocative soundtracks, car shots, and tableaus. Third and lastly I went on to describe the sociocultural aspects of Coppola's interpretation of the "Sling Ring." The way the film explores the relationships between characters, portrays parents as absent or misguided, and through film form shows the pervasiveness of celebrity culture, Sofia Coppola has given Bling Ring has a central ii message, substance, and meaning: glamorous contemporary celebrity culture can have dangerous consequences on unchecked youth. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Astria Suparak Is an Independent Curator and Artist Based in Oakland, California. Her Cross

Astria Suparak is an independent curator and artist based in Oakland, California. Her cross- disciplinary projects often address urgent political issues and have been widely acclaimed for their high-level concepts made accessible through a popular culture lens. Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art institutions and festivals across ten countries, including The Liverpool Biennial, MoMA PS1, Museo Rufino Tamayo, Eyebeam, The Kitchen, Carnegie Mellon, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, and Expo Chicago, as well as for unconventional spaces such as roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, sports bars, and rock clubs. Her current research interests include sci-fi, diasporas, food histories, and linguistics. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE (selected) . Independent Curator, 1999 – 2006, 2014 – Present Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art, film, music, and academic institutions and festivals across 10 countries, as well as for unconventional spaces like roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, elementary schools, sports bars, and rock clubs. • ART SPACES, BIENNIALS, FAIRS (selected): The Kitchen, MoMA PS1, Eyebeam, Participant Inc., Smack Mellon, New York; The Liverpool Biennial 2004, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), England; Museo Rufino Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; FotoFest Biennial 2004, Houston; Space 1026, Vox Populi, Philadelphia; National -

From Surrealism to Now

WHAT WE CALL LOVE FROM SURREALISM TO NOW IMMA, Dublin catalogue under the direction of Christine Macel and Rachael Thomas [Cover] Wolfgang Tillmans, Central Nervous System, 2013, inkjet print on paper mounted on aluminium in artist’s frame, frame: 97 × 82 cm, edition of 3 + 1 AP Andy Warhol, Kiss, 1964, 16mm print, black and white, silent, approx. 54 min at 16 frames per second © 2015 THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM, PITTSBURG, PA, COURTESY MAUREEN PALEY, LONDON. © WOLFGANG TILLMANS A MUSEUM OF CARNEGIE INSTITUTE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. FILM STILL COURTESY OF THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM. PHOTO © CENTRE POMPIDOU, MNAM-CCI, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / GEORGES MEGUERDITCHIAN CONTENTS E 1 FOREWORD Sarah Glennie 6 WHAT WE CALL LOVE Christine Macel 13 SURREALISM AND L’AMOUR FOU FROM ANDRÉ BRETON TO HENRIK OLESEN / FROM THE 1920s TO NOW 18 ANDRÉ BRETON AND MAD LOVE George Sebbag 39 CONCEPTUAL ART / PERFORMANCE ART FROM YOKO ONO TO ELMGREEN AND DRAGSET / FROM THE 1960s TO NOW 63 NEW COUPLES FROM LOUISE BOURGEOIS TO JIM HODGES / FROM THE 1980s TO NOW 64 AGAINST DESIRE: A MANIFESTO FOR CHARLES BOVARY? Eva Illouz 84 THE NEUROBIOLOGY OF LOVE Semir Zeki 96 LOVE ACTION Rachael Thomas WHAT 100 LIST OF WORKS 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY WE CALL LOVE CHAPTER TITLE F FOREWORD SARAH GLENNIE, DIRECTOR The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) is pleased to present this publication, which accompanies the large scale group exhibition, What We Call Love: From Surrealism to Now. This exhibition was initially proposed by Christine Macel (Chief Curator, Centre Pompidou), who has thoughtfully curated the exhibition alongside IMMA’s Rachael Thomas (Senior Curator: Head of Exhibitions). -

Female Improvisational Poets: Challenges and Achievements in the Twentieth Century

FEMALE .... improvisational - ,I: t -,· POETS ...~1 Challenges and Achievements in the Twentieth Century In December 2009, 14,500 people met at the Bilbao Exhibi tion Centre in the Basque Country to attend an improvised poetry contest.Forty-four poets took part in the 2009 literary tournament, and eight of them made it to the final. After a long day of literary competition, Maialen Lujanbio won and received the award: a big black txapela or Basque beret. That day the Basques achieved a triple triumph. First, thou sands of people had gathered for an entire day to follow a lite rary contest, and many more had attended the event via the web all over the world. Second, all these people had followed this event entirely in Basque, a language that had been prohi bited for decades during the harsh years of the Francoist dic tatorship.And third, Lujanbio had become the first woman to win the championship in the history of the Basques. After being crowned with the txapela, Lujanbio stepped up to the microphone and sung a bertso or improvised poem refe rring to the struggle of the Basques for their language and the struggle of Basque women for their rights. It was a unique moment in the history of an ancient nation that counts its past in tens of millennia: I remember the laundry that grandmothers of earlier times carried on the cushion [ on their heads J I remember the grandmother of old times and today's mothers and daughters.... • pr .. Center for Basque Studies # avisatiana University of Nevada, Reno ISBN 978-1-949805-04-8 90000 9 781949 805048 ■ .~--- t _:~A) Conference Papers Series No. -

My Name Is Corrina and I'm the Founder of Bechdel Test Fest

My name is Corrina and I’m the founder of Bechdel Test Fest - an ongoing celebration of women in film. I’m also a freelance critic for Empire Magazine and most recently have produced a documentary on Ava Duvernay for the BBC and have had the pleasure of working with debbie tucker green on the release of her forthcoming new film. In addition I am the resident film critic for Sunday Brunch once a month on Channel 4. I previously worked for Picturehouse Entertainment distribution company but now... My name is corrina and I’m the founder of Bechdel Test Fest - an ongoing celebration of women in film. I’m also a freelance critic for Empire Magazine and most recently have produced a documentary on Ava Duvernay for the BBC and have had the pleasure of working with debbie tucker green on the release of her forthcoming new film. In addition I am the resident film critic for Sunday Brunch once a month on Channel 4 I previously worked for Picturehouse Entertainment distribution company but now.... ...For the day job, I am the arts and culture comms officer for Hackney Council which has me working on events such as Windrush Festival, Hackney’s Anti Racism Plan, Carnival, Black History Season, Hackney Black History Curriculum and the forthcoming Census. I’m Hackney born and bred so... Right now, due to the pandemic, Bechdel Test Fest has been unable to screen films of course but we are still committed to celebrating the work of female-identifying women in film via our Friday newsletter and social which promotes all the week’s new releases and our podcast Who Is She which spotlights and usually interviews a brilliant female filmmaker. -

Political Goals Versus Commercial Goals: Emile De Antonio's Rush To

Media Industries 6.2 (2019) Political Goals versus Commercial Goals: Emile de Antonio’s Rush to Judgment on the Market Nora Stone1 UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS AT LITTLE ROCK norastone [AT] gmail.com Abstract Emile de Antonio had reason to hope that his second documentary, Rush to Judgment (1967), would be as popular as his first, Point of Order! (1963). Made with bestselling author and political commentator Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment was one of the very first films to question the Warren Commission’s conclusion about the Kennedy assassination. However, despite its topicality, Rush to Judgment did not entice exhibitors or audiences. While de Antonio and others attributed the film’s commercial failure to politically motivated censorship and intimidation, this explanation does not account for other factors in the documentary’s release. Using trade journals and Emile de Antonio’s archive, this article finds that Rush to Judgment’s release was hobbled by an inexperienced and dysfunctional distribution company and by de Antonio and Lane’s divergent goals. Most of all, though, the instability of the independent film market in the mid-1960s sunk the release of Rush to Judgment. Keywords: Film Distribution, Documentary, Committed Documentary, Political Emile de Antonio’s first film, Point of Order!, was a surprise success at the box office in 1964. Made with Dan Talbot, owner of the recently opened arthouse New Yorker Theater and later founder of distribution company New Yorker Films, Point of Order! tells the story of the infa- mous Army–McCarthy hearings of 1954. Distributor Walter Reade-Sterling booked Point of Order! in over one hundred cinemas, as well as numerous college campuses. -

Identifying Missing Component in the Bechdel Test Using Principal Component Analysis Method Raghav Lakhotia, Chandra Kanth Nagesh, Krishna Madgula

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Computer and Systems Engineering Vol:13, No:6, 2019 Identifying Missing Component in the Bechdel Test Using Principal Component Analysis Method Raghav Lakhotia, Chandra Kanth Nagesh, Krishna Madgula about how women are under-represented on screen. According Abstract—A lot has been said and discussed regarding the to the report "Celluloid Ceiling" [3], "women comprised only rationale and significance of the Bechdel Score. It became a digital 18% of all the directors, writers, producers, editors, executive sensation in 2013, when Swedish cinemas began to showcase the and cinematographers working on the top 250 domestic Bechdel test score of a film alongside its rating. The test has drawn grossing films in 2017". While in 2016, only 12% of films out criticism from experts and the film fraternity regarding its use to rate the female presence in a movie. The pundits believe that the score is of 900 had a balanced cast [4]. Men outnumber women in the too simplified and the underlying criteria of a film to pass the test film industry as well. The issue has long prevailed in the must include 1) at least two women, 2) who have at least one industry since, but the question arises; did we highlight this dialogue, 3) about something other than a man, is egregious. In this gender bias to the extent that we should have? research, we have considered a few more parameters which highlight In 1985, Alison Bechdel, an American cartoonist, invented how we represent females in film, like the number of female a score [5] to gauge gender equality on screen. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films,