The Production and Distribution of Roman Military Equipment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Materials for a Rejang-Indonesian-English Dictionary

PACIFIC LING U1STICS Series D - No. 58 MATERIALS FOR A REJANG - INDONESIAN - ENGLISH DICTIONARY collected by M.A. Jaspan With a fragmentary sketch of the . Rejang language by W. Aichele, and a preface and additional annotations by P. Voorhoeve (MATERIALS IN LANGUAGES OF INDONESIA, No. 27) W.A.L. Stokhof, Series Editor Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Jaspan, M.A. editor. Materials for a Rejang-Indonesian-English dictionary. D-58, x + 172 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1984. DOI:10.15144/PL-D58.cover ©1984 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A - Occasional Papers SERIES B - Monographs SERIES C - Books SERIES D - Special Publications EDITOR: S.A. Wurm ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W. Bender K.A. McElhanon University of Hawaii University of Texas David Bradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii A. Capell P. MUhlhiiusler University of Sydney Linacre College, Oxford Michael G. Clyne G.N. O'Grady Monash University University of Victoria, B.C. S.H. Elbert A.K. Pawley University of Hawaii University of Auckland K.J. Franklin K.L. Pike University of Michigan; Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W. Grace Malcolm Ross University of Hawaii University of Papua New Guinea M.A.K. -

BASE BALL, TRAP SHOOTING and GENERAL SPORTS Tills Registered in IT

DEVOTED TO BASE BALL, TRAP SHOOTING AND GENERAL SPORTS Tills Registered in IT. S. Patent OBce. Copyright. 1914, by the Sporting Life PnblisMue Company. Vol. 54-No. 21 Philadelphia, January 29, 1910 Price 5 Cents E PLAYING RULES! Are Being Given B. Johnson With a Complete Over a View to Sub hauling by Two mission to the Experts at the In Joint Rules Com stance of Ban. mittee Next Month BY I. E. SANBORN. former guides the rules stated a bstrauni TOP entitled to first base -without being pa* oui HIOAGO, ILL., January 24. By r«- in such a case, and the omission, accidental quest of President Johnson, of the in itself, has been overlooked. Saci. imper American League, his secretary, fections are not freqxtent, but their discovery Robert McRoy and Assistant Sec is possible only by careful^ inspection, for retary A. J. Flanner are engaged which the members of the joint rules com in a thorough revision of the code mittee will not have time at the coming meat- ing. Any suggestions of radical changes will, of playing rules, primarily with a of course, be left to the committees. riew to correcting mistakes that have crept into them and avoiding apparent conflicts and AS TO "BATTERY ERRORS." misinterpretations through imperfect wording. One of minor importance which probably Incidentally changes not of a radical nature will be suggested by the American League, will be suggested, and their work will be put however, affects the scoring rules in that wild pitches and passed balls should ba in definite form to be presented to the credited as errors in all cases. -

New Series. Norwalk, Conn

AT TWO DOLLARS PER ANNUM—IN ADVANCE. JSSJRFSD EVERY TUESDA^ MORNING, BY A. HOMER BYINGTON, itt 1800. |1oIitus, ^gritnltatt, Mttbanits, ftt fUts, titration;, &. &.- % J»% Btfes^cr.—gcbdcij to f«al S*te f* Iittesfs> ©mtal gsfeJIijorct, fitainrc, VOLUME XXXVI.—NUMBER 28. -^= NORWALK, CONN DAY, JULY 12, 1853. fairest expectations with a suicidal rash XUMBEB S89---NEW SERIES. Iter—and, giving "her birth, her mother while he was employed with his studies hiding her face in tns lap, while the curls ness. O, God! why was I so reckless ?" had died, "if she left bim, he would be W. E. 2 P B o& & 4'a & c feigning a siesta, but in reality watching of her shining hair swept the floor. "O, The idea of meeting with Lelia seemed a lone, childless old mail, fc>r llkely he OULD invite the alention of this and As clsitscture. and loving him. Slle was jealous of Herman, my husband, do not leave me, infinitely worse than death. In his the neighboring coiBiiunity to his vast FriemtdsM??. should' never see her again. Bes.,,les'lie A. H. SYHTS-TOS, Editor & Proprietor. W his slightest attentions to others, and she dear Herman! do not go again to that dreams he nightly beheld her, but she stock of goods.\t 6 which artlitions are weekly [We copy below, from Barry's "Hor- IIow oft the burdened heart would sink had required this pledge before marriage, being made.) comprising araill and general as Office West Side the .Bridge in Leonard s ticulturis," a very valuable essay on a In fathomless despair, delighted in lavishing costly gifts upon cold country. -

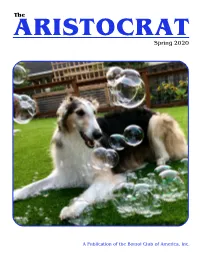

The Spring 2020

The ARISTOCRAT Spring 2020 A Publication of the Borzoi Club of America, Inc. Executive Officers President: Ron Williams, 155 Libertyville Rd., Wantage, NJ 07461, 973-721-4146, [email protected] Vice-President: Carol Enz, Box 876, Ramah, NM 87321-0876, 505-783-4743, [email protected] Treasurer: Janis A. Leikam, PO Box 2328, Shelton WA 98584, 360-427-0417, [email protected] Recording Secretary: Joy Windle, 2255 Strasburg Rd., Coatesville, PA 19320-4437, 610-380-0850, [email protected] Corresponding Secretary: Barbara Danieli, 3431 Eagle Drive, Troy, MI 48083, 248-761-8409, [email protected] AKC Delegate: Prudence Hlatky, 4511 CR 121, Rosharon, TX 77583-59591979, 281-840-2753, [email protected] Regional Governors Region 1 Kari McCloskey, 152 Neill Run Road, Delta, PA 17314, 443-243-5241, [email protected] Region 2: Elizabeth Tolley, 875 Mockingbird Drive, Brighton, TN 38011-6889, 901-497-4594 [email protected] Region 3: Shirley McFadden PO Box 454 Axtell, TX 76624-0454, 254-315-4166, [email protected] Region 4: Lorrie Scott 1728 Hanson Lane Ramona, CA 92065-3311, 760-789-6848, [email protected] Region 5: Karen Ackerman, PO Box 507 Upton, WY 82730-0507, 307-468-2696, [email protected] Region 6: Joyce Katona, 7617 Pelham Drive, Chesterland, OH 44026-2011, [email protected] 2019 Standing Committee Chairs Annual Awards Nancy Katsarelas, [email protected] Annual Top 5 Awards Leonore Abordo, [email protected] Annual Versatility Award & Versatility Hall Of Fame Kay Novotny, [email protected] Archivist K.C. Artley, [email protected] Aristocrat Helen W. Lee, Editor, [email protected] ASFA Delegate Sandra Moore, [email protected] Beverly C. -

Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, 11-11-1865 William E

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe Gazette, 1852-1869 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 11-11-1865 Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, 11-11-1865 William E. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sf_gazette_news Recommended Citation Jones, William E.. "Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, 11-11-1865." (1865). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sf_gazette_news/371 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe Gazette, 1852-1869 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CTA'Tvrm a "creí proa í lira 1 uAalü l ia "INDEPENDENT. IN ALL THINGS, NEUTRAL IN NOTHING." Volume VIL SANTA FE, ISTEW MEXICO. NOVEMBER 11, 1S65. Number 22. ahtrtistiiitntj. Sania Jt Mcclili ttt, Ihutisniuiits. aiincrtinnitnts. bbtrtistiwnts. lerlistiiifnis. PTBUSHU) EVERY SATURDAY HORNING AT IWAIRICK KIEt KD.U'II. M. D., UNITED STATUS M AHA rocuivotl before tb last dnjr for Z. STAAB & BRO. othor routes whore tho mnilo of convoyanrt dated nd SANTA FE, HEW MEXICO. SURGEON AN'D ntimiU ot'it.'tlio .jpocittl ;ont of tho Post retielvin propufiiL. PHYSICIAN, lliiví1 by two - ríi ftlvodaiiJ keep cnunuiilly uu lmul a largo Office depttrtinunt, also post otlico blanks, Each bid must be ctnrantmd ri- iWHurtnienl of TKRIIITORY OF KEW IH EllC'O. M.i. ... iti.a 1.; anA wtinr.nt.il OBSTETRICIAN. mail bite, locks and keys, aro to be con- COLLINS, with th. full nm JAMK3 L. voyed without extra charge. -

Schaller's Book Store

The Ann Arbor VOL. XXIV. NO. 18. ANN AKBOB, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, MAY 5.1808. WHOLE NO. 1219. A GENEROUS_GIFT THE I'MVIiHMTV RECEIVES $142, QUEER CASE OF SIX OOO Flion THE I'UOPERTY OF A 8THANGI5K. LADIES, LISTEN! Dr. Elizabeth II. Bates, a New York Reported that County and City Officers Capture a Half Dozen Lady, the Douer. Bauker D. H. If you will come into our store while down Smith, o! IIHuoes, Brought the Selfishness town we will show you a large selection of.... Boys-Are All Locked in Jail Then All Are Set Free Rood News. The Univtrsity authorities had a most pleasant and unexpected surprise is not considered one of the cardi- last Monday. A fino looking old gen- nal virtues, yet nearly all our METALIC BELTS tleman came up the walk to the main actions in life are governed by self- FOR A VALUABLE MONEY CONSIDERATION hall and asked for Mr. Wade. Upon ish considerations. It is self inter- est that makes people look after of the latest designs. being taken to the president's office to the money they are spending very ntroduced himself as D. H. Smith, a carefully these days; and we are Our spring styles of Shirt Waist Buttons, No Justice Courts Show Records of Trial-Boys Claim They banker from Princeton, 111., and execu- free to confess that it is also self tor of the estate of Dr. Elizabeth H. interest that moves us when we Cuff Buttons, etc., has also arrived. Were Told They Must Pay a Certain Amount or Stay Bates, of Port Chester, New York. -

2019 Submitted by K.C

New Title Holders Earned January, February & March 2019 Submitted by K.C. Artley, [email protected] AKC Conformation Champion (CH) CH Journey Of Matrioshka (D) Evermore At Majenkir, br/ow: Karen CH Bella Luna Land O’ Lakes (D) HP55272801, 09-Aug-2017, by Staudt-Cartabona HP43304807, 05-Jun-2012, by CH Octavian Z Bilmy & Afternoon Delight CH Morozova Rey’s Foreign Affair @ Laureate Bella Luna Fly Me To The Matrioshka, br: Vendula Svobodova, Joshua (B) HP48314001, 21-Aug- Moon CD RN JC & Adrienne Zooropa ow: Nancy Harvey & Heidi Smith 2014, by Am/Can CH Taugo’s Ulric La Paloma, br: Elizabeth Moon & CH Kelcorov’s Winter Is Coming SC & GCH Morozova’s Emmalyne, br: Janis Leikam, ow: Elizabeth Moon (B) HP45380002, 10-Jun-2013, by Janet Adams & Kathleen Novotny, ow: CH Bella Luna Moon Goddess Of Golightly By Daylight SC & CH Cynthia Tellefsen & Beverly Peck Dakamar (B) HP55648402, 03-May- Kelcorov’s Vashda Nirada, br/ow: CH Morozova Rey’s California Poppy (B) 2018, by GCHB Laureate Higgs Boson Bunny Kelley HP51513502, 15-Mar-2016, by CH & CH Adrienne Bella Luna Once In CH Justart Birdsong At Majenkir (B) Hemlock Hollow Aruzia The Journey A Lifetime, br: Elizabeth Moon, ow: HP49004205, 24-Jan-2015, by Am/ Continues JC & GCHS Morozova Debra Maldonado Can CH Taugo’s Ulric & CH Majenkir Sierra Sunrise At Rey JC ROM-C, br/ CH C’Lestial Bachelors Button JC (D) Hunter’s Dawn, br/ow: Stuart McGraw ow: Kathleen Novotny & Janet Adams HP40426314, 14-May-2011, by & Justine Spiers & Karen Staudt- CH Oxota Molodezovna Manika SC C’Lestial Pure Perfection -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

Eastern Shoshone Working Dictionary

Eastern Shoshone Working Dictionary Compiled by David Leedom Shaul This is a working dictionary based of the published and publicly accessible sources for Eastern Shoshone. The NSF DEL Eastern Shoshone project is to accumulate all of the known information about Eastern Shoshone words into a database. This has included gathering together several major sources, from both published sources and manuscripts. The project was slated to work with native speakers, but because the Shoshone Business Council was not able to identify a Shoshone coordinator as a liaison, this phase has not been possible. Instead, a large database has been accumulated of Eastern Shoshone words and phrases. A list was first made of all published dictionaries and vocabularies of Shoshone (Idaho, Utah, Nevada). In this way, it is possible to tell if a Eastern Shoshone word is shared with the other dialects of the language. This pan-Shoshone list was originally made as a checklist for work with Eastern Shoshone speakers so that no word would be overlooked. Sources for Eastern Shoshone Words and Phrases The main published and publicly accessible sources for Eastern Shoshone are listed below, along with the abbreviations used in the working dictionary. E Eastern Shoshone Cultural Center (2004) Geb Gebow (1869, 1868) Hi Hill (n.d.) Hul Hultkrantz (1987); Trehero and Hultkrantz (2009) Mor Moore (n.d.) Rob Roberts (n.d.) S St. Clair ( [1901] ) S dis Shimkin (1953; published version) Sh Shimkin field notes (n.d.) SG Shimkin grammar sketch (n.d.) SGE Shimkin ethnogeography (1947a) SM Shimkin morpheme list (1949a, 1949b) T Tidzump (n.d.; 1970); Tidzump and Kosin 1 (1967a, 1967b) Van Vander (1978) One major source of data is the morpheme list from the the Eastern Shoshone texts collected in 1901 by Harry Hull St. -

Arjiy Will Take Over Air Mails Feb. 19

. -‘ r : 4 ' ' ' ■ ■ ■ ............ '.* • • : t:4 4TSBAGE DAILY dBCDLATION for ttie Month of iramisry, 19S4 Poreeaat of p. 8. Wenther 5 , 3 6 7 Snrtford Member of the Antflt Fair, not quite so eold tonlgltt; Snodmj iaereMliif AiniMWi.*— BoroM of dreiilntioiis. 7mZT^ mow at nlj^t. VOL. u n . NO. 112. (CbMolfled Advertlalng on Page 10.) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 10,1934. (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE (^ENTB RIOTS PU RE ANEW Figures In Bremer Kidnaping EATHS, BLAZES OLLOW STATES ARJIY WILL TAKE OVER IN PARIS STREETS COLDEST SPELL Commimist Bands Start AIR MAILS FEB. 19 CONNOR MAKES Man, Exposure Victim, Wom Trouble; Several Fatali Private Fliers Stripped of an Bamed to Death; Big Expect Arrest Today ties, 1,000 Injured; Dou- ANOTHER PLEA Their Contracts by One Fire in Hartford, Another mergne Issues Appeal. TO MOTORISTS Of Former Air Chief Swift Government B lo w - Reported in New Britain. Washington, Feb. 10.— (AP)—The^court proceedings to test the right Some Companies Say It Paris, Feb. 10— (AP)—Commun Encouraged by Last Week’s arrest of William P. MacCraeken ! of the Senate to arrest a private ist bands which had created a night By ASSOCIATED PRESS. was expected momentarily today by citizen. Arramgements were under- Will Force Them Ont of of terror were cleared from miles of Success, State Official officieils, following his defiance of stood to have been made for him to riot-ridden streets just before dawn Slowly rising temperatures todav the Senate by refusing to appear to give himself up to Chesley W. Jur- today. brought relief from the Intense cold face contempt charges. -

Native American Sourcebook: a Teacher's Resource on New England Native Peoples. INSTITUTION Concord Museum, MA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 406 321 SO 028 033 AUTHOR Robinson, Barbara TITLE Native American Sourcebook: A Teacher's Resource on New England Native Peoples. INSTITUTION Concord Museum, MA. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 238p. AVAILABLE FROMConcord Museum, 200 Lexington Road, Concord, MA 01742 ($16 plus $4.95 shipping and handling). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; American Indian History; *American Indian Studies; *Archaeology; Cultural Background; Cultural Context; *Cultural Education; Elementary Secondary Education; Instructional Materials; Social Studies; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Algonquin (Tribe); Concord River Basin; Native Americans; *New England ABSTRACT A major aim of this source book is to provide a basic historical perspective on the Native American cultures of New England and promote a sensitive understanding of contemporary American Indian peoples. An emphasis is upon cultures which originated and/or are presently existent in the Concord River Basin. Locally found artifacts are used in the reconstruction of past life ways. This archaeological study is presented side by side with current concerns of New England Native Americans. The sourcebook is organized in six curriculum units, which include:(1) "Archaeology: People and the Land";(2) "Archaeology: Methods and Discoveries";(3) "Cultural Lifeways: Basic Needs";(4) "Cultural Lifeways: Basic Relationships"; (5) "Cultural Lifeways: Creative Expression"; and (6) "Cultural Lifeways: Native Americans Today." Background information, activities, and references are provided for each unit. Many of the lessons are written out step-by-step, but ideas and references also allow for creative adaptations. A list of material sources, resource organizations and individuals, and an index conclude the book.