Vuillaume: Reality and Myth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B&F Magazine Issue 31

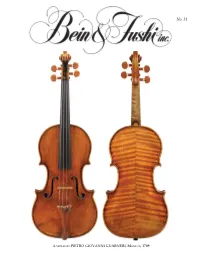

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

World Flavors & Fragrances

R Industry Study Freedonia forecasts to 2008 & 2013 for 17 countries & 6 regions World Flavors & Fragrances Study # 1886 January 2005 $5100 Global demand to cially strong, advancing 7.3 percent per year through Western Europe increase 4.4% per 2008. Growth in the world’s 29% year through 2008 most developed markets will continue to be moder- Global demand for flavors ate, restrained by market and fragrances is forecast maturity, consolidation in North America to increase 4.4 percent per flavor and fragrance using 28% year to US$18.6 billion in industries and strong 2008. Developing nations downward pressure on will continue to record prices. better growth than industri- Asia/Pacific 27% alized regions such as Historically, flavor and Western Europe, North fragrance production has World Flavors America and Japan; and been dominated by the US, & Fragrances blends will grow faster than Japan and Western Europe Other Regions 16% Demand both aroma chemicals and -- in particular, France, the essential oils. Pricing United Kingdom, Germany (US$18.6 billion, 2008) pressures will also remain and Switzerland. However, an issue primarily due to a these areas will lose chemicals than more basic foods, health foods and shrinking customer base. market share through 2008 foodstuffs. Demand for nutraceuticals, confections, However, some slight to developing areas of the fragrance blends and cosmetics and skin care easing is expected due to world, where producers are essential oils will benefit products, pharmaceuticals, growing requirements for attracted to above-average from increased interest in and niche markets such as better quality, higher value growth in flavor and natural and exotic aromas, aromatherapy. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

45 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Labels mentions an early form of Del Gesù label, 98 later re - jected by the Hills as spurious. 99 The strongest evi - Before closing the body of the instrument, Del dence for its existence is found in the earlier Gesù fixed his label on the inside of the back, beneath notebooks of Count Cozio Di Salabue, who mentions the bass soundhole and roughly parallel to the centre four violins by the younger Giuseppe, all labelled and line. The labels which remain in their original posi - dated, from the period 1727 to 1730. -

Countries Supported by the Solaredge Inverters

August 2021 Countries Supported by the SolarEdge Inverters The SolarEdge inverters can be used in many different countries. This document details countries where SolarEdge approves installation of its inverters. Installation should always be done in compliance with local regulations, and in case of a conflict between local regulations and this document, local regulations apply. Summary The SolarEdge inverters may be installed in the following countries. Unless stated otherwise, the approval refers to low voltage installations. For medium voltage installations, please contact SolarEdge support. Please refer to the country details below for more information, as in some countries not all grids are supported or not all inverter models are supported. In supported countries, connection of supported inverters to non-supported grids is permitted through a transformer, if the secondary connection (transformer connection to the inverter) is identical to a supported grid. NOTE Transformer procurement, installation, maintenance and support are the responsibility of the installer. Damage to the inverter due to incorrect transformer installation or use of a transformer that is incompatible with the SolarEdge system will render the SolarEdge warranty invalid. NOTE Prior to purchasing a StorEdge system verify battery availablity and service in the country. Availability of SolarEdge StorEdge products does not guarantee battery availabllity. A country listed in bold indicates that StorEdge Inverters with backup are approved for installation in that country. -

The Strad Magazine

FRESH THINKING WOOD DENSITOMETRY MATERIAL Were the old Cremonese luthiers really using better woods than those available to other makers FACTS in Europe? TERRY BORMAN and BEREND STOEL present a study of density that seems to suggest otherwise Violins await testing on a CT scanner gantry S ALL LUTHIERS ARE WELL AWARE, of Stradivari. To test this conjecture, we set out to compare the business of making an instrument of the the wood employed by the classical Cremonese makers with violin family is fraught with pitfalls. There that used by other makers, during the same time period but are countless ways to ruin the sound of the from various regions across Europe. This would eliminate one fi nished product, starting with possibly the variable – the ageing of the wood – and allow the tracking of Amost fundamental decision of all: what wood to use. In the past geographical and topographical variation. In particular, we 35 years we have seen our knowledge of the available options wanted to investigate the densities of the woods involved, which expand greatly – and as we learn more about the different wood we felt could be the key to unlocking these secrets. choices, it is increasingly hard not to agonise over the decision. What are the characteristics we need as makers? Should we just WHY DENSITY? look for a specifi c grain line spacing, or a good split? Those were The three key properties of wood, from an instrument maker’s the characteristics that makers were once taught to watch out perspective, are density, stiffness (‘Young’s modulus’) and for, and yet results are diffi cult to repeat from instrument to damping (in its simplest terms, a measure of how long an object instrument when using the same pattern – suggesting these are will vibrate after being set in motion). -

Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 Knightsbridge, London

Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 Knightsbridge, London Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 at 12pm Knightsbridge, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services Please see back of catalogue Montpelier Street Director of Department Monday to Friday for Notice to Bidders Knightsbridge Philip Scott 8.30am to 6pm London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3855 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 New bidders must also provide proof www.bonhams.com [email protected] of identity when submitting bids. Illustrations Failure to do this may result in your Viewing Specialist Front cover: Lot 273 & 274 bids not being processed. Friday 9 May Thomas Palmer Back cover: Lot 118 +44 (0) 20 7393 3849 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] IMPORTANT Saturday 10 May INFORMATION 11am to 5pm The United States Government Department Fax has banned the import of ivory Sunday 11 May +44 (0) 20 7393 3820 11am to 5pm Live online bidding is into the USA. Lots containing available for this sale ivory are indicated by the symbol Customer Services Ф printed beside the lot number Bids Please email [email protected] Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm with “Live bidding” in the in this catalogue. +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax subject line 48 hours before To bid via the internet the auction to register for Please register and obtain your this service. please visit www.bonhams.com customer number/ condition report for this auction at Please provide details of the lots [email protected] on which you wish to place bids at least 24 hours prior to the sale. -

Countries Supported by the Solaredge Inverters the Solaredge Inverters Can Be Used in Many Different Countries

Last update: Nov. 2016 Countries Supported by the SolarEdge Inverters The SolarEdge inverters can be used in many different countries. This document details countries where SolarEdge approves installation of its inverters. Installation should always be done in compliance with local regulations, and in case of a conflict between local regulations and this document, local regulations apply. Summary The SolarEdge inverters may be installed in the following countries. Unless stated otherwise, the approval refers to low voltage installations. For medium voltage installations, please contact SolarEdge support. Please refer to the country details below for more information, as in some countries not all grids are supported or not all inverter models are supported. In supported countries, connection of supported inverters to non-supported grids is permitted through a transformer, if the secondary connection (transformer connection to the inverter) is identical to a supported grid. NOTE Transformer procurement, installation, maintenance and support are the responsibility of the installer. Damage to the inverter due to incorrect transformer installation or use of a transformer that is incompatible with the SolarEdge system will render the SolarEdge warranty invalid. NOTE Prior to purchasing a StorEdge system verify battery availablity and service in the country. Availability of SolarEdge StorEdge products does not guarantee battery availabllity. A country listed in bold indicates that StorEdge inverters with backup are approved for installation -

Musical Instruments, 30 October 2013, Knightsbridge, London

Wednesday 30 October 2013 at 11am 30 October 2013 at Wednesday London Knightsbridge, Instruments Musical Musical 20770 Musical Instruments, 30 October 2013, Knightsbridge, London Musical Instruments Wednesday 30 October 2013 at 11am Knightsbridge, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services Please see back of catalogue Montpelier Street Director of Department Monday to Friday for Notice to Bidders Knightsbridge Philip Scott 8.30am to 6pm London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3855 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 New bidders must also provide proof www.bonhams.com [email protected] of identity when submitting bids. Illustrations Failure to do this may result in your Viewing Specialist Front cover: Lot 230 bids not being processed. Sunday 27 October Thomas Palmer Back cover: Lot 3 +44 (0) 20 7393 3849 11am to 3pm [email protected] Monday 28 October 9am to 4.30pm Department Fax Tuesday 29 October +44 (0) 20 7393 3820 9am to 4.30pm Live online bidding is available for this sale Customer Services Bids Please email [email protected] Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm with “Live bidding” in the +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax subject line 48 hours before To bid via the internet the auction to register for Please register and obtain your this service. please visit www.bonhams.com customer number/ condition report for this auction at Please provide details of the lots [email protected] on which you wish to place bids at least 24 hours prior to the sale. New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting bids. -

Photo Report

Richard Nixon Presidential Library: Photo Report ● 1895-1. Richard Nixon's Mother, Hannah Milhous Nixon. Jennings Co., Indiana. B&W. Source: copied into White House Photo Office. Alternate Numer: B-0141 Hannah Milhous Nixon ● 18xx-1. Richard Nixon's paternal grandfather, Samuel Brady Nixon. B&W. Samuel Brady Nixon ● 1916-1. Family portrait with Richard Nixon (age 3). 1916. California. B&W. Harold Nixon, Frank Nixon, Donald Nixon, Hannah Nixon, Richard Nixon ● 1917-1. Portrait of Richard Nixon (age 4). 1917. California. B&W. Richard Nixon, Portrait ● 1930-1. Richard Nixon senior portrait (age 17), as appeared in the Whittier High School annual. 1930. Whittier, California. B&W. Richard Nixon, Yearbook, Portrait, Senior, High School, Whittier High School ● 1945-1. Formal portrait of Richard Nixon in uniform (Lieutenant Commander, USN). Between October, 1945 (date of rank) and March, 1946 (date of discharge). B&W. Richard Nixon, Portrait, Navy, USN, Uniform ● 1946-1. Richard Nixon, candidate for Congress, discusses the election with the Republican candidates for Attorney General Fred Howser and for California State Assemblyman Montivel A. Burke at a GOP rally in honor of Senator Knowland (R-Ca). 1946. El Monte, California. B&W. Source: Photo by Dot and Larry, 2548 Ivar Avenue, Garvey, California, Phone Atlantic 15610 Richard Nixon, Fred Howser, Montivel Burke, Campaign, Knowland ● 1946-2. Congressman Carl Hinshaw and Richard Nixon shake hands during a campaign. 1946. B&W. Carl Hinshaw, Richard Nixon, Campaign, Handshake ● 1946-3. Senator William F. Knowland (R-CA) being greeted by Claude Larrimer (seated) of Whittier at a GOP rally (barbeque/entertainment) in honor of the former.