Reproducing and Resisting the Binary: Discursive Conceptualizations of Gender Variance in Children’S Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flourishing of Transgender Studies

BOOK REVIEW The Flourishing of Transgender Studies REGINA KUNZEL Transfeminist Perspectives in and beyond Transgender and Gender Studies Edited by A. Finn Enke Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012. 260 pp. ‘‘Transgender France’’ Edited by Todd W. Reeser Special issue, L’Espirit Createur 53, no. 1 (2013). 172 pp. ‘‘Race and Transgender’’ Edited by Matt Richardson and Leisa Meyer Special issue, Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (2011). 147 pp. The Transgender Studies Reader 2 Edited by Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura New York: Routledge, 2013. 694 pp. For the past decade or so, ‘‘emergent’’ has often appeared alongside ‘‘transgender studies’’ to describe a growing scholarly field. As of 2014, transgender studies can boast several conferences, a number of edited collections and thematic journal issues, courses in some college curricula, and—with this inaugural issue of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly—an academic journal with a premier university press. But while the scholarly trope of emergence conjures the cutting edge, it can also be an infantilizing temporality that communicates (and con- tributes to) perpetual marginalization. An emergent field is always on the verge of becoming, but it may never arrive. The recent publication of several new edited collections and special issues of journals dedicated to transgender studies makes manifest the arrival of a vibrant, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly * Volume 1, Numbers 1–2 * May 2014 285 DOI 10.1215/23289252-2399461 ª 2014 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/tsq/article-pdf/1/1-2/285/485795/285.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 286 TSQ * Transgender Studies Quarterly diverse, and flourishing interdisciplinary field. -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

Transgender Representation on American Narrative Television from 2004-2014

TRANSJACKING TELEVISION: TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION ON AMERICAN NARRATIVE TELEVISION FROM 2004-2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Kelly K. Ryan May 2021 Examining Committee Members: Jan Fernback, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Ron Becker, External Member, Miami University ABSTRACT This study considers the case of representation of transgender people and issues on American fictional television from 2004 to 2014, a period which represents a steady surge in transgender television characters relative to what came before, and prefigures a more recent burgeoning of transgender characters since 2014. The study thus positions the period of analysis as an historical period in the changing representation of transgender characters. A discourse analysis is employed that not only assesses the way that transgender characters have been represented, but contextualizes American fictional television depictions of transgender people within the broader sociopolitical landscape in which those depictions have emerged and which they likely inform. Television representations and the social milieu in which they are situated are considered as parallel, mutually informing discourses, including the ways in which those representations have been engaged discursively through reviews, news coverage and, in some cases, blogs. ii To Desmond, Oonagh and Eamonn For everything. And to my mother, Elaine Keisling, Who would have read the whole thing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the research and writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance, and therefore offer many thanks. To my Dissertation Chair, Jan Fernback, whose feedback on my writing and continued support and encouragement were invaluable to the completion of this project. -

Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. INCLUSIVE STORIES Although scholars of LGBTQ history have generally been inclusive of women, the working classes, and gender-nonconforming people, the narrative that is found in mainstream media and that many people think of when they think of LGBTQ history is overwhelmingly white, middle-class, male, and has been focused on urban communities. While these are important histories, they do not present a full picture of LGBTQ history. To include other communities, we asked the authors to look beyond the more well-known stories. Inclusion within each chapter, however, isn’t enough to describe the geographic, economic, legal, and other cultural factors that shaped these diverse histories. Therefore, we commissioned chapters providing broad historical contexts for two spirit, transgender, Latino/a, African American Pacific Islander, and bisexual communities. -

Police Department Model Policy on Interactions with Transgender People

POLICE DEPARTMENT MODEL POLICY ON INTERACTIONS WITH TRANSGENDER PEOPLE National Center for TRANSGENDER EQUALITY This model policy document reflects national best policies and practices for police officers’ interactions with transgender people. The majority of these policies were originally developed by the National LGBT/HIV Criminal Justice Working Group along with a broader set of model policies addressing issues including police sexual misconduct and issues faced by people living with HIV. Specific areas of the original model policy were updated and modified for use as the foundation for NCTE’s publication “Failing to Protect and Serve: Police Department Policies Towards Transgender People,” which also evaluates the policies of the largest 25 police departments in the U.S. This publication contains model language for police department policies, as well as other criteria about policies that should be met for police departments that seek to implement best practices. The larger Working Group’s model policies developed by Andrea J. Ritchie and the National LGBTQ/HIV Criminal Justice Working Group, a coalition of nearly 40 organizations including NCTE, can be found in the appendices of the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) “Gender, Sexuality, and 21st Century Policing” report. While these are presented as model policies, they should be adapted by police departments in collaboration with local transgender leaders to better serve their community. For assistance in policy development and review, please contact Racial and Economic Justice Policy Advocate, Mateo De La Torre, at [email protected] or 202-804-6045, or [email protected] or 202-642-4542. NCTE does not charge for these services. -

Make Education Fair Senate Submission

August 08 Senate Submission: Academic Freedom ACADEMIC FREEDOM MAKE EDUCATION FAIR 13th August 2008 Committee Secretary Senate Education, Employment and Workplace Relations Committee Department of the Senate SUBMISSION TO SENATE INQUIRY INTO ACADEMIC FREEDOM The Young Liberal movement and the Australian Liberal Students Federation are gravely concerned about fairness in education. We welcome the opportunity to provide a submission into the inquiry into Academic Freedom, representing the voice of mainstream students across the country. Make Education Fair Campaign Bias at our high schools and university campuses has reached epidemic proportions. Many of our student members have approached us with numerous stories of this bias being expressed by teachers, reflected in the curriculum or in a hostile atmosphere for students who cannot freely express their views. We would like to ensure that all students continue to have the right to exercise freedom of thought and expression, without fear of reprisal or penalty. Over the past few months, the Make Education Fair campaign has actively sourced examples from students who have experienced bias on university campuses. The depth of academic bias uncovered by this campaign, most notably in the arts faculties of Australia’s major universities, is gravely disturbing and poses significant challenges for diversity within the education sector. The examples that have been provided to us indicate the following problems with academic freedom within Australia: • A lack of diversity amongst academics and the -

Online Questionnaires

Online Questionnaires Re-thinking Transgenderism The Trans Research Review • Understanding online trans communities. • Comprehending present-day transvestism. • Inconsistent definitions of ‘transgenderism’ and the connected terms. • !Information regarding • Transphobia. • Family matters with trans people. • Employment issues concerning trans people. • Presentations of trans people within media. The Questionnaires • ‘Male-To-Female’ (‘MTF’) transsexual people [84 questions] ! • ‘MTF’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [83 questions] ! • ‘Significant Others’ (Partners of trans people) [49 questions] ! • ‘Female To Male’ (‘FTM’) transsexual people [80 questions] ! • ‘FTM’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [75 questions] ! • ‘Trans Admirers’ (Individuals attracted to trans people) • [50 questions] The Questionnaires 2nd Jan. 2007 to ~ 12th Dec. 2010 on the international Gender Society website and gained 390,227 inputs worldwide ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 204 ‘Female-To-Male’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 0.58 1 - Understanding online trans communities. Transgender Support/Help Websites ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: (679 responses) Always 41 Often 206 Sometimes 365 Never 67 0 100 200 300 400 1 - Understanding -

From Civil Rights to Women's Liberation: Women's Rights in SDS

From Civil Rights to Women’s Liberation: Women’s Rights in SDS and SNCC, 1960-1969 Anna Manogue History 4997: Honors Thesis Seminar 6 May 2019 2 “I had heard there was some infighting in the Women’s March between Jewish women and Black women, and I’m a Native American woman and I think it’s ridiculous that we’re dividing ourselves like this. We’re all women,” proclaimed Barbara McIlvaine Smith as she prepared to attend the third annual Women’s March in January of 2019.1 Smith’s comments succinctly summarized the ideological controversy over the intersection of race and gender— known since 1991 as intersectionality or intersectional feminism—that has plagued feminist activism since the emergence of the Women’s Liberation Movement in 1968.2 The concept of interactions between racial and sexual forms of oppression first emerged in the early 1960s, when women in the Civil Rights Movement began to identify similarities between the racial oppression they were fighting and the unequal treatment of women within their organizations. Many women asserted that their experiences as civil rights activists refined their understanding of gender inequality, improved their community organizing skills, and inspired their support of feminism.3 Historians have long acknowledged that women in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) first contemplated the connection between women’s rights and civil rights in the early 1960s and ultimately inspired their fellow women in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) to instigate the Women’s Liberation Movement in 1968.4 During the 1960s, SNCC and SDS both gained reputations as staunchly democratic organizations dedicated to empowering students and creating a more equal society. -

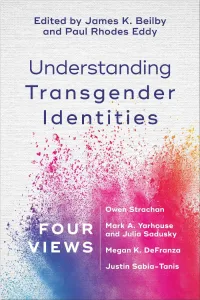

Understanding Transgender Identities

Understanding Transgender Identities FOUR VIEWS Edited by James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy K James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 3 9/11/19 8:21 AM Contents Acknowledgments ix Understanding Transgender Experiences and Identities: An Introduction Paul Rhodes Eddy and James K. Beilby 1 Transgender Experiences and Identities: A History 3 Transgender Experiences and Identities Today: Some Issues and Controversies 13 Transgender Experiences and Identities in Christian Perspective 44 Introducing Our Conversation 53 1. Transition or Transformation? A Moral- Theological Exploration of Christianity and Gender Dysphoria Owen Strachan 55 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 84 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 90 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 95 2. The Complexities of Gender Identity: Toward a More Nuanced Response to the Transgender Experience Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 101 Response by Owen Strachan 131 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 136 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 142 3. Good News for Gender Minorities Megan K. DeFranza 147 Response by Owen Strachan 179 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 184 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 190 vii James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 7 9/11/19 8:21 AM viii Contents 4. Holy Creation, Wholly Creative: God’s Intention for Gender Diversity Justin Sabia- Tanis 195 Response by Owen Strachan 223 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 228 Response by Megan K. -

Unsw's Student Magazine / May 2017

UNSW'S STUDENT MAGAZINE / MAY 2017 WOMEN C CREATIVE WE'D LOVE FOR YOU TO JOIN US ON THE INTERNET. THARUNKA 10 MY BODY IS POWERFUL @THARUNKAUNSW @THARUNKA 23 BLEMISH GIVE US A LIKE AND A FOLLOW AND A RETWEET AND SEND 24 THE TRUTH WHATEVER YOU HAVE TO SAY TO [email protected] THE TEAM (WRITING, ARTWORK, IDEAS, FEEDBACK, LOVE LETTERS, PICTURES OF / 25 THEY TOLD US TO WEAR RED CUTE DOGS – WE WANT IT ALL). MANAGING EDITOR 26 NECESSARY AND DESIRABLE. BRITTNEY RIGBY O 28 HBO’S BIG LITTLE LIES TELLS A LOT OF TRUTHS FOR WOMEN SUB-EDITORS ALICIA D'ARCY, SHARON WONG, 29 HOW TO PLAN FOR IMMINENT DEATH CONTENT WARNING DOMINIC GIANNINI 30 YOU DO YOU THIS ISSUE DEALS WITH THEMES OF: DESIGNER 32 TO THREE WOMEN I'VE MET LEO TSAO -DOMESTIC VIOLENCE / -SEXUAL ASSAULT CONTRIBUTORS ABBY BUTLER, AMY GE, CATHERINE -TRANSPHOBIC VIOLENCE MACAROUNAS, CATHY TAN, ELLA CANNON, EMMA KATE WILSON, HANNAH WOOTTON, -SUICIDE HERSHA GUPTA, ISABELLA OLSSON, JENI N ROHWER, JUMAANA ABDU, KAIT POLKINGHORNE, LARA ROBERTSON, LIZZIE BUTTERWORTH, MICHELLE WANG, OLIVIA INWOOD, ROSE COX, SABEENA MOZAFFAR, SARAH HORT FEATURES / 09 WHY THEORY ISN'T EVERYTHING: THARUNKA ACKNOWLEDGES THE TRADITIONAL COMPLACENCY AND THE CASE OF THE CUSTODIANS OF THIS LAND, THE GADIGAL AND DISAPPEARING MAN BEDIGAL PEOPLE OF THE EORA NATION, ON WHICH OUR UNIVERSITY NOW STANDS. BLOODY WOMEN N 11 T www.tharunka.arc.unsw.edu.au O T 12 ARE COLLEGES SEXIST OR SAFE? THARUNKA IS PUBLISHED PERIODICALLY BY Arc @ UNSW. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED HEREIN 18 THE MANIC PIXIE DREAM GIRL AND ME E C ARE NOT NECESSARILY THE VIEWS OF ARC, THE E 19 A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A "PERIOD C REPRESENTATIVE COUNCIL OR THE THARUNKA REGULARS N SKIPPER" EDITING TEAM, UNLESS EXPRESSLY STATED. -

Terminology Packet

This symbol recognizes that the term is a caution term. This term may be a derogatory term or should be used with caution. Terminology Packet This is a packet full of LGBTQIA+ terminology. This packet was composed from multiple sources and can be found at the end of the packet. *Please note: This is not an exhaustive list of terms. This is a living terminology packet, as it will continue to grow as language expands. This symbol recognizes that the term is a caution term. This term may be a derogatory term or should be used with caution. A/Ace: The abbreviation for asexual. Aesthetic Attraction: Attraction to someone’s appearance without it being romantic or sexual. AFAB/AMAB: Abbreviation for “Assigned Female at Birth/Assigned Male at Birth” Affectionional Orientation: Refers to variations in object of emotional and sexual attraction. The term is preferred by some over "sexual orientation" because it indicates that the feelings and commitments involved are not solely (or even primarily, for some people) sexual. The term stresses the affective emotional component of attractions and relationships, including heterosexual as well as LGBT orientation. Can also be referred to as romantic orientation. AG/Aggressive: See “Stud” Agender: Some agender people would define their identity as not being a man or a woman and other agender people may define their identity as having no gender. Ally: A person who supports and honors sexual diversity, acts accordingly to challenge homophobic, transphobic, heteronormative, and heterosexist remarks and behaviors, and is willing to explore and understand these forms of bias within themself. -

Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Undergraduate Engineering Students: Perspectives, Resiliency, and Suggestions for Improving Engineering Education

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Andrea Evelyn Haverkamp for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Engineering presented on January 22, 2021. Title: Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Undergraduate Engineering Students: Perspectives, Resiliency, and Suggestions for Improving Engineering Education Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Michelle K. Bothwell Gender has been the subject of study in engineering education and science social research for decades. However, little attention has been given to transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) experiences or perspectives. The role of cisgender or gender conforming status has not been investigated nor considered in prevailing frameworks of gender dynamics in engineering. The overwhelming majority of literature in the field remains within a reductive gender binary. TGNC students and professionals are largely invisible in engineering education research and theory and this exclusion causes harm to individuals as well as our community as a whole. Such exclusion is not limited to engineering contexts but is found to be a central component of systemic TGNC marginalization in higher education and in the United States. This dissertation presents literature analysis and results from a national research project which uses queer theory and community collaborative feminist methodologies to record, examine, and share the diversity of experiences within the TGNC undergraduate engineering student community, and to further generate community-informed suggestions for increased support and inclusion within engineering education programs. Transgender and gender nonconforming participants and researchers were involved at every phase of the study. An online questionnaire, follow-up interviews, and virtual community input provided insight into TGNC experiences in engineering contexts, with relationships between race, gender, ability, and region identified.