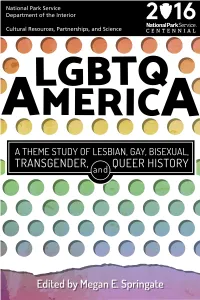

Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cold War Beginnings

GROWTH AND TURMOIL, 1948-1977 Cold War Beginnings Resource: Life Story: Christine Jorgensen (1926-1989) Christine Jorgensen was born on May 30, 1926, in the Bronx, New York. She was assigned male at birth, but always felt like a girl. She wanted to wear girls’ clothes and play with girls’ toys. As a teenager, she developed crushes on boys and struggled to understand her own feelings. After she graduated from high school in 1945, Christine was drafted by the U.S. Army. Christine served as a military clerical worker for a year. After World War II ended, Christine pursued a career in photography. In her free time, she read about medical procedures to help people who felt that their gender or sexual identity did not align with society’s expectations. In 1950, she traveled to Denmark for a series of surgeries and hormone treatments that transformed her body into that of a woman. The process took nearly two years. She chose the name Christine in honor of her surgeon, Dr. Christian Hamburger. Christine intended for her transition to remain private. However, an unidentified person who knew about the procedures she had contacted the press. On December 1, 1952, the New York Daily News published photographs of Christine before and after her transition with the headline “Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty: Operations Transform Bronx Youth.” Within days, Christine Jorgensen was both a national and international celebrity. When she returned to the United States in 1953, Christine arranged with the press to make her arrival a public spectacle. Hundreds of reporters greeted her at the airport in New York City. -

“Jorgensen Enjoys Being Christine”: Christine Jorgensen's Public Image

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC 2021 Undergraduate Presentations Research Day 2021 2021 “Jorgensen Enjoys Being Christine”: Christine Jorgensen’s Public Image and How It Shaped a Movement Giovanni Esparza Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/ug_pres_2021 “Jorgensen Enjoys Being Christine”: Christine Jorgensen’s Public Image and How It Shaped a Movement By: Giovanni Esparza Mentors: Joan Clinefelter and Chris Talbot Historical Questions Key Terms 1. In what ways did Jorgensen both positively progress and negatively complicate the transsexual movement? - Transvestite: By their terms, was a person who dressed in clothes of the opposite gender. 2. How did Jorgensen articulate her understanding of gender? - Transsexual: Someone who changes their body in order to match the gender they identify with. 3. And in so doing, how did she become a key figure of social movements concerned with issues of sexuality - Transgender: An umbrella term that means having a gender identity or gender expression that differs and gender? from the sex that they were assigned at birth. Humble Beginnings Book, Movie, and Lectures • Jorgensen joined the military in 1945, but never saw war. • Jorgensen decided to write an autobiography about her • Jorgensen, still a male, tried to get a career in Hollywood life and publish it in 1967. but never managed to do so, eventually moving back to • Jorgensen then decided to produce a movie on her life New York to attend college where she read The Male based on the book. Hormone by Paul de Kruif. • The book sold thousands of copies around the United • In 1950, she decided to travel to Copenhagen, Denmark States and the world and the movie was also widely where she would officially change her gender. -

Affirmative Practice with Transgender Clients

Affirmative Practice with Transgender Clients lore m. dickey, PhD Assistant Professor Department of Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Louisiana Tech University Dedication In memory of trans* people who are no longer with us. Kyle Scanlon Overview of Presentation Professional standards Foundational knowledge Addressing risk & trauma Addressing resilience Internalized transprejudice Advocacy with TGNC Clients Historical Perspective Christine Jorgensen In truth Fa’afafine Hijra Two Spirit Kathoey Burnesha Mahu Professional Standards What we have so far … Professional Standards, Competencies, & Guidelines World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH, 2011) Standards of Care (SOC) American Counseling Association (ACA, 2010) Training Competencies American Psychological Association (APA) Practice Guidelines WPATH SOC First published in 1979 7th version published 2011 Topics covered Epidemiological concerns Therapeutic approaches Children, Adolescents, & Adults Mental Health WPATH SOC “The SOC are intended to be flexible in order to meet the diverse health care needs of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people.” (p. 2) WPATH SOC “… the expression of gender characteristics, including identities that are not stereotypically associated with one’s assigned sex at birth, is a common and culturally-diverse human phenomenon [that] should not be judged as inherently pathological or negative.” (p. 4.) ACA Competencies Published in 2010 Written from multicultural, social justice, and feminist perspective -

Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War

History in the Making Volume 9 Article 5 January 2016 Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War Heather K. Garrett CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Heather K. (2016) "Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War," History in the Making: Vol. 9 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War By Heather K. Garrett Abstract: When asked of their memory of the American Revolution, most would reference George Washington or Paul Revere, but probably not Molly Pitcher, Lydia Darragh, or Deborah Sampson. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to demonstrate not only the lack of inclusivity of women in the memory of the Revolutionary War, but also why the women that did achieve recognition surpassed the rest. Women contributed to the war effort in multiple ways, including serving as cooks, laundresses, nurses, spies, and even as soldiers on the battlefields. Unfortunately, due to the large number of female participants, it would be impossible to include the narratives of all of the women involved in the war. -

A Photo Essay of Transgender Community in the United States

Sexuality Research & Social Policy Journal of NSRC http://nsrc.sfsu.edu December 2007 Vol. 4, No. 4 Momentum: A Photo Essay of the Transgender Community in the United States Over 30 Years, 1978–2007 Mariette Pathy Allen As a photographer, writer, advocate, and ally of the Figure 1. Vicky West (in center of photograph) at the transgender community, I have presented slide shows at hotel swimming pool, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1978. a variety of conferences during the past 30 years. I have varied the slide shows according to the audience and, to challenge myself, asked various questions about my art. What fresh visual connections can I make? How do my newest images relate to earlier series? Shall I focus on indi- vidual heroes and heroines—community leaders—or on dramatic historical events that galvanized people to rethink their lives and demand policy changes? Is it appro- priate to show body images and surgery? Should I focus on youth and relationships? What about speaking of my life as an artist and how it connects to the transgender community? Long before I knowingly met a transgender person, I pondered such questions as, Why are certain character traits assigned to men or to women? and Are these traits in different directions except for one person, Vicky West, immutable or culturally defined? My cultural anthropol- who focused straight back at me. As I peered through the ogy studies offered some theories, but it was not until camera lens, I had the feeling that I was looking at nei- 1978, when I visited New Orleans for Mardi Gras, that I ther a man nor a woman but at the essence of a human came face to face with the opportunity to explore gender being; right then, I decided that I must have this person identity issues through personal experience. -

MASTERCLASS Meet

MASTERCLASS Meet uPaul Charles’s chameleonic qualities have made him a television icon, spiritual guide, and R the most commercially successful drag queen in United States history. Over a nearly three-decade career, he’s ushered in a new era of visibility for drag, upended gender norms, and highlighted queer talent from across the world—all while dressed as a fierce glamazon. “Be willing to become the shape-shifter that you absolutely are.” Born in San Diego, California, RuPaul first experienced mainstream success when a dance track he wrote called “Supermodel (You Better Work)” became an unexpected MTV hit (Ru stars in the music video). The song led to a modeling contract with MAC Cosmetics and a talk show on VH1, which saw RuPaul interviewing everyone from Nirvana to the Backstreet Boys and Diana Ross to Bea Arthur. He has since appeared in more than three dozen films and TV shows, including Broad City, The Simpsons, But I’m a Cheerleader!, and To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar. RuPaul’s Drag Race, Ru’s decade-old, Emmy-winning reality drag competition, has gone international, with spin-offs set in the U.K. and Thailand. He’s also published three books: 2 RuPaul 1995’s Lettin’ It All Hang Out, 2010’s Workin’ It!, and 2018’s GuRu, which features a foreword from Jane Fonda. Recently, he became the first drag queen to land the cover of Vanity Fair. His Netflix debut, AJ and the Queen, premiered on the streaming service in January 2020. RuPaul saw drag as a tool that would guide his punk rock, anti-establishment ethos. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-81478-2

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-81478-2 - The New York Concert Saloon: The Devil’s Own Nights Brooks Mcnamara Index More information Index NOTE: The Society for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency is abbreviated to SPJD. Abbey, The 120 temperance and abstinence Abe, the Pioneer, or the Mad Hunter of Arizona movements 12 (melodrama) 39 in theatres 20–1, 35 Academy of Fun, The 48, 56, 63 Alhambra Theatre 39 acrobats 16, 31, 48, 54, 118–19 Allen, John 109 Actors’ Fund 28 Allen, Robert C. xix. 3 acts 41–60 Allen, William (“Billy”) 43, 66, 81 as advertising device 29, 59, 76 amateur performances 32–3, 117 ethnic performers 4–5, 79–80 American Concert Hall 28 and immorality charges 2, 12, 17–18, 20 American Hall 49 professional 49–50, 77–8, 117, 130–1 amusement parks 9 range before Concert Bill 15–16 Arion 128, 130, 131 SPJD documents on 57–60, 130–1 Arizona Star 119 see also acrobats; child actors; circus; dance Asbury, Herbert xvi, xx, 82, 107, 110–11 acts; drag acts; magic acts; minstrelsy; “Asmodeus” 75, 81, 85, 86 musical entertainments; puppet shows; Assembly 23–4 sketches; songs; women (performers); and assignations 25, 83, 119–20 under beer gardens, German; dance Athenaeum 585, 37, 39 houses; variety theatre Atlantic Garden 27, 100, 101–3, 104, 127 advertising xiii, 9, 62–4 Audran, Edmond 36 of “bar maids” 31 entertainments as 26, 59, 76 Bailey, James 8 handbills 62, 110 Baker’s Central Hall 33 medicine shows and xiii, 9, 33 balconies in newspapers 28, 37, 42, 62 concert saloons 73–4, 76 sandwich boards 62 dance houses 106, 107, 112, 113 signs 63–4, 107 flat floor opera houses 117 stock poster 71, 72 German beer gardens 98, 102 transparencies 25, 62–3 San Francisco box houses 119–20 African Americans 79–80 Ballard’s What Is It 42, 61, 63, 75, 90, 92 afterpieces 6–7, 57 ballet girls 20, 85 alcohol Baltimore 77, 117 in German beer gardens 96, 99 bar maids 31 and immorality 2, 12, 17–18, 20 Barnum, P. -

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lvovsky, Anna. 2015. Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463142 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 A dissertation presented by Anna Lvovsky to The Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of American Civilization Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Anna Lvovsky All rights reserved. Advisor: Nancy Cott Anna Lvovsky Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 Abstract This dissertation tracks how urban police tactics against homosexuality participated in the construction, ratification, and dissemination of authoritative public knowledge about gay men in the -

The Female Review

The Female Review wife and children; soon after, mother Deborah Bradford Sampson The Female Review (1797) put five-year-old Deborah out to service in various Massachusetts Herman Mann households. An indentured servant until age eighteen, Sampson, now a “masterless woman,” became a weaver (“one of the very few androgynous trades in New England,” notes biographer Text prepared by Ed White (Tulane University) and Duncan Faherty (Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center). We want to thank Paul Erickson and Alfred Young [40]), then a rural schoolteacher, then, near age the American Antiquarian Society for their tremendous support, and Jodi twenty-one, a soldier in the Continental Army (37). Donning Schorb (University of Florida) for contributing the following introduction. men’s clothes (not for the first time, as it turns out) and adopting the generic name “Robert Shurtliff,” the soldier fought in several skirmishes, suffered battle injuries (to either the groin or upper Mann Seeking Woman: body), and was eventually promoted to serving as “waiter” (an Reading The Female Review officer’s orderly) to brigadier general John Paterson. Sampson’s military career has been most carefully Jodi Schorb reconstructed by Alfred F. Young in Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier. Although The Female Review In the wake of the American Revolution and beyond, claims Sampson/Shurtliff enlisted in 1781 and fought at the Battle Deborah Sampson was both celebrity and enigma, capturing the of Yorktown (September-October, 1781), Sampson/Shurtliff 1 imagination of a nation that had successfully won their actually served in the Continental Army from May, 1782 until independence from England. -

Bourbon, Ray (1892?-1971) by Claude J

Bourbon, Ray (1892?-1971) by Claude J. Summers Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Legendary drag performer and recording artist Ray (or Rae) Bourbon appeared in silent movies, vaudeville acts, Broadway plays, and, from the 1930s through the 1960s, performed across the United States in a gay nightclub circuit. Often arrested by the police for his "indecent" performances and for dressing in drag, Bourbon was ultimately convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and died in prison. Bourbon deliberately obscured his origins, sometimes even claiming that he was "the last of the Hapsburg Bourbons," but he was probably born Hal Waddell in Texarkana, Texas sometime around 1892. In the early 1920s, Bourbon worked as a stuntman in Hollywood and appeared in several silent films, sometimes in drag. He then teamed up with Bert Sherry in a successful vaudeville act, "Bourbon and Sherry," in which Sherry played the straight man to Bourbon's flamboyant drag persona. He soon attracted the attention of Mae West, who in 1927 cast him in two of her plays--Sex and Pleasure Man. Both were raided by police who were attempting to "clean up" Broadway. Bourbon later appeared as an extra in West's movies and in supporting roles in productions of her plays. In the early 1930s, Bourbon recorded the first of his many risqué records. He also began to appear in the "pansy clubs" that sprouted in Hollywood in an attempt to capitalize on the "pansy craze" in New York during the late 1920s. Bourbon created and starred in a drag revue called "Boys Will Be Girls." After the police shut down the Los Angeles establishments, he moved his show to San Francisco. -

Chapter Six: Activist Agendas and Visions After Stonewall (1969-1973)

Chapter Six: Activist Agendas and Visions after Stonewall (1969-1973) Documents 103-108: Gay Liberation Manifestos, 1969-1970 The documents reprinted in The Stonewall Riots are “Gay Revolution Comes Out,” Rat, 12 Aug. 1969, 7; North American Conference of Homophile Organizations Committee on Youth, “A Radical Manifesto—The Homophile Movement Must Be Radicalized!” 28 Aug. 1969, reprinted in Stephen Donaldson, “Student Homophile League News,” Gay Power (1.2), c. Sep. 1969, 16, 19-20; Preamble, Gay Activists Alliance Constitution, 21 Dec. 1969, Gay Activists Alliance Records, Box 18, Folder 2, New York Public Library; Carl Wittman, “Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto,” San Francisco Free Press, 22 Dec. 1969, 3-5; Martha Shelley, “Gay is Good,” Rat, 24 Feb. 1970, 11; Steve Kuromiya, “Come Out, Wherever You Are! Come Out,” Philadelphia Free Press, 27 July 1970, 6-7. For related early sources on gay liberation agendas and philosophies in New York, see “Come Out for Freedom,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 1; Bob Fontanella, “Sexuality and the American Male,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 15; Lois Hart, “Community Center,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 15; Leo Louis Martello, “A Positive Image for the Homosexual,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 16; “An Interview with New York City Liberationists,” San Francisco Free Press, 7 Dec. 1969, 5; Bob Martin, “Radicalism and Homosexuality,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. 1970, 4; Allan Warshawsky and Ellen Bedoz, “G.L.F. and the Movement,” Come Out!,” 10 Jan. 1970, 4-5; Red Butterfly, “Red Butterfly,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. 1970, 4-5; Bob Kohler, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. QUEEREST28 LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD: LGBTQ RENO John Jeffrey Auer IV Introduction Researchers of LGBTQ history in the United States have focused predominantly on major cities such as San Francisco and New York City. This focus has led researchers to overlook a rich tradition of LGBTQ communities and individuals in small to mid-sized American cities that date from at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century.