Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Female Review

The Female Review wife and children; soon after, mother Deborah Bradford Sampson The Female Review (1797) put five-year-old Deborah out to service in various Massachusetts Herman Mann households. An indentured servant until age eighteen, Sampson, now a “masterless woman,” became a weaver (“one of the very few androgynous trades in New England,” notes biographer Text prepared by Ed White (Tulane University) and Duncan Faherty (Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center). We want to thank Paul Erickson and Alfred Young [40]), then a rural schoolteacher, then, near age the American Antiquarian Society for their tremendous support, and Jodi twenty-one, a soldier in the Continental Army (37). Donning Schorb (University of Florida) for contributing the following introduction. men’s clothes (not for the first time, as it turns out) and adopting the generic name “Robert Shurtliff,” the soldier fought in several skirmishes, suffered battle injuries (to either the groin or upper Mann Seeking Woman: body), and was eventually promoted to serving as “waiter” (an Reading The Female Review officer’s orderly) to brigadier general John Paterson. Sampson’s military career has been most carefully Jodi Schorb reconstructed by Alfred F. Young in Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier. Although The Female Review In the wake of the American Revolution and beyond, claims Sampson/Shurtliff enlisted in 1781 and fought at the Battle Deborah Sampson was both celebrity and enigma, capturing the of Yorktown (September-October, 1781), Sampson/Shurtliff 1 imagination of a nation that had successfully won their actually served in the Continental Army from May, 1782 until independence from England. -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

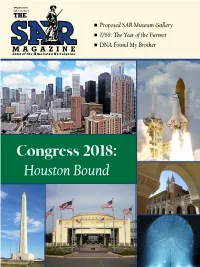

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. INCLUSIVE STORIES Although scholars of LGBTQ history have generally been inclusive of women, the working classes, and gender-nonconforming people, the narrative that is found in mainstream media and that many people think of when they think of LGBTQ history is overwhelmingly white, middle-class, male, and has been focused on urban communities. While these are important histories, they do not present a full picture of LGBTQ history. To include other communities, we asked the authors to look beyond the more well-known stories. Inclusion within each chapter, however, isn’t enough to describe the geographic, economic, legal, and other cultural factors that shaped these diverse histories. Therefore, we commissioned chapters providing broad historical contexts for two spirit, transgender, Latino/a, African American Pacific Islander, and bisexual communities. -

American Ha the Midnight Ride of Dr

t’s B ha B g in os r? W rewin ton rbo RevolutionAmerican Ha The Midnight Ride of Dr. Prescott ? Hey, Guys! Wait a PITCHER’S Minute! PETTICOAT PERILS IN PARTNERSHIP WITH American_Revolution_FC.indd 1 3/13/17 12:57 PM 2 and coming to America. They did so for many reasons: religious freedom, making Americans Revolt! money, and a new life, among others. Ma- If you sometimes don’t want to do what ny colonists had their differences with your parents tell you, then you have an Britain. But most still considered them- idea of how Great Britain’s 13 American selves loyal subjects of the Crown. colonies felt in the 1770s. Since the 16th Starting around 1763, after the end of century, people had been leaving Britain the rench an nian War con ict in Their tax protests But, in fact, they might make you had the highest think the American per capita (per colonists suffered person) income of financially (in any people in the terms of money). world. American_Revolution_2-3.indd 2 3/13/17 12:58 PM 3 creased between Britain and the colonies. representation in Parliament. The British Great Britain had fought to drive the offered to let the colonists elect represen- French from the continent. Britain won tatives to Parliament. The colonists reject- but had huge war debts. Parliament (the ed that idea. They thought they would nev- lawmaking body of Britain) said the colo- er get enough votes to have any real power. nies should help pay these debts. The Conict beteen the colonists an ritain Americans resisted. -

ID Key Words Folder Name Cabinet 21 American Revolution, Historic

ID key words folder name cabinet 21 american revolution, historic gleanings, jacob reed, virginia dare, papers by Minnie Stewart Just 1 fredriksburg, epaulettes francis hopkins, burnes rose, buchannan, keasbey and mattison, boro council, tennis club, athletic club 22 clifton house, acession notes, ambler gazette, firefighting, east-end papers by Minnie Stewart Just 1 republcan, mary hough, history 23 faust tannery, historical society of montgomery county, Yerkes, Hovenden, ambler borough 1 clockmakers, conrad, ambler family, houpt, first presbyterian church, robbery, ordinance, McNulty, Mauchly, watershed 24 mattison, atkinson, directory, deeds 602 bethlehem pike, fire company, ambler borough 1 butler ave, downs-amey, william harmer will, mount pleasant baptist, St. Anthony fire, newt howard, ambler borough charter 25 colonial estates, hart tract, fchoolorest ave, talese, sheeleigh, opera house, ambler borough 1 golden jubilee, high s 26 mattison, asbestos, Newton Howard, Lindenwold, theatre, ambler theater, ambler/ambler borough 1 Dr. Reed, Mrs. Arthur Iliff, flute and drum, Duryea, St. Marys, conestoga, 1913 map, post office mural, public school, parade 27 street plan, mellon, Ditter, letter carriers, chamber of commerce, ambler ambler/ambler borough 1 directory 1928, Wiliam Urban, fife and drum, Wissahickon Fire Company, taprooms, prohibition, shoemaker, Jago, colony club, 28 charter, post cards, fire company, bridge, depot, library, methodist, church, ambler binder 1 colony club, fife and drum, bicentennial, biddle map, ambler park -

Notes and Queries Historical, Biographical, and Genealogical

3 Genet 1 Class BookE^^V \ VOLU M E Pi- Pennsylvania State Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https ://archive, org/details/ notesquerieshist00unse_1 .. M J L U Q 17 & 3 I at N . L3 11^ i- Ail ; ' ^ cu^,/ t ; <Uj M. 7 \ \ > t\ v .^JU V-^> 1 4 NOTES AXD QUERIES. and Mrs. Herman A1 ricks were born upon this land. David Cook, Sr., married a j Historical, Biographical and Geneal- Stewart. Samuel Fulton probably left i ogical. daughters. His executors were James Kerr and Ephraim Moore who resided LXL near Donegal church. Robert Fulton, the father of the in- Bcried in Maryland. — In Beard’s ventor who married Mary Smith, sister of Lutheran graveyard, Washington county, Colonel Robert Smith, of Chester county, Maryland, located about one-fourth of a was not of the Donegal family. There mile from Beard’s church, near Chews- seems to be two families of Fultons, and ville, stands an old time worn and dis- are certainly located in the wrong place, j colored tombstone. The following ap- Some of the descendants of Samuel Ful- pears upon its surface: ton move to the western part of Pennsyl- “Epitaphium of Anna Christina vania, and others to New York State. Geiserin, Born March 6, 1761, in the Robert Fulton, the father of the in- province of Pennsylvania, in Lancaster ventor, was a merchant tailor in Lancaster county. -

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania WASHINGTON by JOSEPH WRIGHT, 1784 the Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania WASHINGTON BY JOSEPH WRIGHT, 1784 THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Powel Portrait of Washington by Joseph Wright N THE EARLY 1930's when the selection of the best likeness of Washington for official use during the Washington Bicentennial I was being made, the choice narrowed down to a portrait painted by Joseph Wright for Mrs. Samuel Powel and the bust by Houdon. Though the experts agreed that the portrait was probably the better likeness, the bust was selected since it had long been nationally known. The portrait, on the other hand, had never been on public display and had been seen only by generations of Powels and their friends.1 It was not until the 1930's that it emerged from that state of privacy. Its history dates back to the autumn of 1783 and the arrival at Washington's headquarters at Rocky Hill, near Princeton, New Jersey, of a young artist, Joseph Wright. Born in nearby Borden- town in 1756, the son of Patience Wright, who was probably America's first sculptress, Wright had accompanied his mother to England in 1772. There he studied painting under Benjamin West 1 John C. Fitzpatrick, editor of The Writings of George Washington, told Mr. Powel this anecdote. Robert J. H. Powel, Notes on the "Wright" Portrait of General George Washington, copy provided by the Newport Historical Society. 419 420 NICHOLAS B. WAINWRIGHT October and John Hoppner, who married his sister. After a brief stay in France, where he painted Franklin, he returned to America intent on capturing a likeness of Washington. -

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 184 Margaret Cochran Corbin: Revolutionary Soldier Lead: During the Battle of Fort Washington in November, 1776

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 184 Margaret Cochran Corbin: Revolutionary Soldier Lead: During the Battle of Fort Washington in November, 1776 Molly Corbin fought the British as hard as any man. Intro.: "A Moment in Time" with Dan Roberts. Content: Margaret Corbin was a camp follower. At that time women were not allowed to join military units as combatants but most armies allowed a large number of women to accompany units on military campaigns. They performed tasks such as cleaning and cooking and due to their proximity to battle often got caught up in actual fighting. Mrs. Washington was a highly ranked camp follower. She often accompanied the General on his campaigns and was at his side during the dark winter of 1777 at Valley Forge. Many of these women were married, some were not and occasionally performing those rather dubious social duties associated with a large number of men alone far from home. Margaret Corbin was born on the far western frontier of Pennsylvania. Her parents were killed in an Indian raid and she was raised in the home of her uncle. In 1772 she married John Corbin who, at the outbreak of hostilities in 1776, enlisted in the First Pennsylvania Artillery. He was a matross (as in mattress), an assistant to a gunner. Margaret accompanied her husband having learned his duties when his unit was posted to Fort Washington on Manhattan Island near present day 183rd Street in New York City. They were assigned to a small gun battery at an outpost on Laurel Hill, northeast of the Fort on an out- cropping above the Harlem River. -

Deborah Sampson Gannett (1760 – 1827)

Deborah Sampson Gannett (1760 – 1827) A Local Guide Sharon Public Library 11 North Main Street Sharon, MA 02067 (781) 784-1578 sharonpubliclibrary.org About Deborah Deborah Sampson was born on December 17, 1760 in Plympton, MA to Jonathan and Deborah Sampson. An impoverished family, the Sampsons had 7 children. Deborah’s father, Jonathan, abandoned the family. Deborah worked as an indentured servant, then as a teacher. Physically, she is described as being tall, strong, and agile but plain, with brown hair and eyes. She was intelligent, with a strong knowledge of politics, theology, and war. In 1782, Deborah enlisted in the 4th Massachusetts Regiment under the name Robert Shurtlieff. She saw action in New York against Loyalists and Native Americans. That same year, she was injured in Tarrytown, but escaped discovery by removing a musket ball from her own leg. In 1793, she contracted brain fever in Philadelphia; Dr Barnabas Binney discovered that she was a woman. Though he did not expose her, he did make arrangements for her discharge. As a result, she was honorably discharged in October 1783. While Deborah was away at war, she was expelled from her Baptist congregation for dressing in men’s clothing and enlisting as a soldier. After her discharge, Deborah moved in with her aunt, Alice Walker, in Stoughton. She continued to dress as a man, passing herself off as her “brother, Ephraim,” until she met local farmer Benjamin Gannet. The two married in April 1785 and raised four children: three of their own (Earl Bradford, Mary, and Patience) and one adopted child (Susanna Shepard, a local orphan). -

Deborah Sampson and the Legacy of Herman Mann's the Female Review Judith Hiltner

"The Example of our Heroine": Deborah Sampson and the Legacy of Herman Mann's The Female Review Judith Hiltner Since its first publication in 1797, Herman Mann's The Female Review has been the primary source for information about the childhood and military career of Deborah Sampson, who served for eighteen months in the Continental Army during the American Revolution disguised as a male. Bolstered in part by Mann' s publication of her career, Sampson won some recognition in her lifetime as a pioneering female soldier and public speaker, and has been honored in the twentieth century as namesake for a Liberty Ship (1944), and as Massachusetts State Heroine (1982). But the most substantial legacy of Mann's appropriation of Sampson's career has been its generation of a two-hundred-year Deborah Sampson print industry. Edited and reprinted repeatedly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in lieu of any definitive account of her life, Mann's 1797 "memoirs," along with his and his nineteenth-century editors' subsequent revi sions of her story, have been tapped, selectively and frequently, to tailor a Sampson designed to accommodate a range of competing cultural projects.1 This essay traces Mann's initial project to make of Deborah Sampson a chaste Minerva—a "genteel" and nonthreatening Amazon tailored to embody early national ideology. I show that his 1797 Sampson was a textual creation, with merely a contingent relation to the actual Middleboro, Massachusetts, woman who enlisted for unknown reasons near the end of the Revolutionary War. He shaped Sampson into an icon of "male" patriotism and "female" chastity, responding to his culture's longing for a more androgynous model of early American character.2 As Republican newspaper editor Mann regarded himself as a crucial cultural voice promulgating, among other agendas, the acceptable limits 0026-3079/2000/4101-093$2.50/0 American Studies, 41:1 (Spring 2000): 93-113 93 94 Judith Hiltner for female energy. -

Spies, Saboteurs, Couriers, and Other Heroines Jennifer Batchler and Heather Price

“It Was I Who Did It”: Spies, Saboteurs, Couriers, and Other Heroines Jennifer Batchler and Heather Price Although women and girls supported the war effort in traditional ways, some seized opportunities to serve in ways generally performed by men. The special circumstances of war allowed women to step out of traditional roles and act in ways that were heroic and unexpected for their time. 1. Positions in Occupied Cities, Military Camps, Homes and Offices During the Revolutionary War women worked around common soldiers and commanders alike. They were cooks, laundresses, peddlers, maids and hostesses. With such easy access and the prevailing attitude that women’s minds’ weren’t capable of understanding military concepts, women could gather a great deal of important information. They were able to eavesdrop on conversations regarding troop movements, strategies and strengths as well as gather information on army size, supplies, fortifications and ammunition counts. Washington called these women “Agents in Place” (“Clandestine Women”). One of the most well-known of these women was Anna Smith Strong. She was a member of the Culper Spy Ring which relied on local patriots to gather information for General Washington about the British occupation. Anna devised a system of hanging clothes on her wash line in a code that identified the locations of key British commanders and troop movements. In particular, a black petticoat signaled that operative Caleb Brewster was in town and the number and order of handkerchiefs identified the specific cove in which his boat was moored (Allen 56). Another famous member of the Culper Spy Ring has never been identified. -

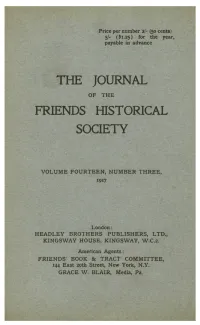

For the Year, Payable in Advance American Agents

Price per number 2/- (50 cents) 5/- ($1.25) for the year, payable in advance THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME FOURTEEN, NUMBER THREE, 1917 London: HEADLEY BROTHERS PUBLISHERS, LTD., KINGSWAY HOUSE, KINGSWAY, W.C.2. American Agents: FRIENDS' BOOK & TRACT COMMITT 144 East 20th Street, New York, N.Y. GRACE W. BLAIR, Media, Pa. CONTENTS Annual Meeting A Private View of London Yearly Meeting in Sessions of 1818 and 1825 97 Presentations in Episcopal Visitations, 1662-1679. Extracted by Prof. G. Lyon Turner, M.A. 105 Richard Smith and his Journal. VI. Compiled by John Dymond Crosfield •. .. .. *. 108 Books Wanted. II... 121 Betsy Ross and the American Flag. By John W. Jordan, LL.D. 122 "Life and Writings of Charles Leslie, M.A., Nonjuring Divine" 123 Friends and Current Literature 127 Recent Accessions to D 132 Notes and Queries:— Quakerism and Pugilism—The Ackworth Scholars—Friends Assist Needy Anglicans— Joseph Liddle, of Preston—Lindley Murray— Attendances at Yearly Meeting—George Logan —Reports of London Y.M.—-Thomas Garrett— James Dickinson—Lydia Darragh and General Washington—Was it Margaret Fell?—Then as Now 136 List of Officers and Financial Statements 142 Vol. XIV. No. 3 W7 THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY For Table of Contents see page two of cover was held on 24th May, when a considerable number of members and others listened with close attention to an address by the President (R. H. Marsh) on the history of the Michael Yoakley Charity. The address, with illustrations, will appear, it is hoped, in the next number of THE JOURNAL.