Women's Involvement in the American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About Women/Loyalists/Patriot

CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 183 Teaching Idea Encourage students to practice read- ing parts of the Declaration of Independence and possibly even Women in the Revolution memorize the famous second section. “Remember the ladies,” wrote Abigail Adams to her husband, John, who was attending the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. While the delegates did not name women in the Declaration of Independence, the “ladies” worked hard for independence. The Daughters of Liberty wove cloth and sewed clothing for the Continental army. Before the war, they had boycotted British imports, including Teaching Idea tea and cloth. The success of these boycotts depended on the support of women, Some women acted as spies during who were responsible for producing most of the household goods. the Revolutionary War. Have students Phillis Wheatley was born in Africa, kidnapped by slavers when she was make invisible ink for getting mes- about seven or eight, and brought to North America. John Wheatley, a rich Boston sages back and forth across enemy merchant, bought her as a servant. His wife, Susannah, taught Wheatley to read lines. For each student, you will need: and write, and she began composing poems as a teenager. Her first book of poet- 4 drops of onion juice, 4 drops of ry was published in London in 1773. The Revolution moved her deeply because lemon juice, a pinch of sugar in a of her own position as a slave, and she composed several poems with patriotic plastic cup, a toothpick to be used as themes, such as “On the Affray [Fighting] in King Street on the Evening of the a writing instrument, and a lamp with 5th of March 1770,” which commemorates the Boston Massacre, and one about an exposed lightbulb. -

Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War

History in the Making Volume 9 Article 5 January 2016 Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War Heather K. Garrett CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Heather K. (2016) "Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War," History in the Making: Vol. 9 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War By Heather K. Garrett Abstract: When asked of their memory of the American Revolution, most would reference George Washington or Paul Revere, but probably not Molly Pitcher, Lydia Darragh, or Deborah Sampson. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to demonstrate not only the lack of inclusivity of women in the memory of the Revolutionary War, but also why the women that did achieve recognition surpassed the rest. Women contributed to the war effort in multiple ways, including serving as cooks, laundresses, nurses, spies, and even as soldiers on the battlefields. Unfortunately, due to the large number of female participants, it would be impossible to include the narratives of all of the women involved in the war. -

Who Has the 2 President of the United States?

I have Benjamin Franklin. I have Paul Revere. I have the first card. Who has a prominent member of the Continental Congress Benjamin Franklin was a prominent that helped with the member of the Continental Declaration of Congress, who helped with the Paul Revere was a Patriot who Declaration of Independence. warned the British were coming. Independence? Who has a patriot who made a daring ride to warn Who has the ruler who colonists of British soldier’s taxed on the colonies? arriving? I have King George III I have the Daughters of Liberty. I have Loyalist. Loyalists were colonists who remained loyal to England King George III taxed the during the Revolutionary The Daughters of Liberty spun colonies. period. Who has the group that cloth in support or the boycott of English goods. Who has the group formed included Martha Washington Who has the term for a in response to the Stamp that spun cloth to support colonist that remained loyal to Act, which is responsible for the boycott of English England? the Boston Tea Party? goods? I have the Sons of Liberty. I have Nathan Hale. I have Patriot. The Sons of Liberty were formed in response to the Stamp Act. Nathan Hale was a Patriot spy that Patriots were in favor of They were responsible for the was hung by the British. independence from England. Boston Tea Party. Who has the American Who has the term for a nd colonist in favor of Who has the 2 spy who was hung by independence from president of the the British? England? United States? I have the John Adams. -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

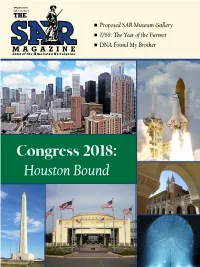

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

How Did Women Support the Patriots During the American Revolutionary War?

Educational materials developed through the Howard County History Labs Program, a partnership between the Howard County Public School System and the UMBC Center for History Education. How did Women Support the Patriots During the American Revolutionary War? Historical Thinking Skills Assessed: Sourcing, Critical Reading, Contextualization Author/School/System: Barbara Baker and Drew DiMaggio, Howard County School Public School System, Maryland Course: United States History Level: Elementary Task Question: How did women support the Patriots during the American Revolutionary War? Learning Outcomes: Students will be able to contextualize and corroborate two sources to draw conclusions about women’s contributions to the American Revolution. Standards Alignment: Common Core Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy RI.5.3 Explain the relationships or interactions between two or more individuals, events, ideas, or concepts in a historical, scientific, or technical text based on specific information in the text. W.5.1 Write opinion pieces on topics or texts, supporting a point of view with reasons and information. SL.5.1 Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions with diverse partners on grade 5 topics and texts, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly. SL.5.1a Come to discussions prepared, having read or studied required material; explicitly draw on that preparation and other information known about the topic to explore ideas under discussion. SL.5.1d Review the key ideas expressed and draw conclusions in light of information and knowledge gained from the discussions. National History Standards Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s) Standard 2: The impact of the American Revolution on politics, economy, and society College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies Standards D2.His.5.3-5 Explain connections among historical contexts and people’s perspectives at the time. -

American Ha the Midnight Ride of Dr

t’s B ha B g in os r? W rewin ton rbo RevolutionAmerican Ha The Midnight Ride of Dr. Prescott ? Hey, Guys! Wait a PITCHER’S Minute! PETTICOAT PERILS IN PARTNERSHIP WITH American_Revolution_FC.indd 1 3/13/17 12:57 PM 2 and coming to America. They did so for many reasons: religious freedom, making Americans Revolt! money, and a new life, among others. Ma- If you sometimes don’t want to do what ny colonists had their differences with your parents tell you, then you have an Britain. But most still considered them- idea of how Great Britain’s 13 American selves loyal subjects of the Crown. colonies felt in the 1770s. Since the 16th Starting around 1763, after the end of century, people had been leaving Britain the rench an nian War con ict in Their tax protests But, in fact, they might make you had the highest think the American per capita (per colonists suffered person) income of financially (in any people in the terms of money). world. American_Revolution_2-3.indd 2 3/13/17 12:58 PM 3 creased between Britain and the colonies. representation in Parliament. The British Great Britain had fought to drive the offered to let the colonists elect represen- French from the continent. Britain won tatives to Parliament. The colonists reject- but had huge war debts. Parliament (the ed that idea. They thought they would nev- lawmaking body of Britain) said the colo- er get enough votes to have any real power. nies should help pay these debts. The Conict beteen the colonists an ritain Americans resisted. -

ID Key Words Folder Name Cabinet 21 American Revolution, Historic

ID key words folder name cabinet 21 american revolution, historic gleanings, jacob reed, virginia dare, papers by Minnie Stewart Just 1 fredriksburg, epaulettes francis hopkins, burnes rose, buchannan, keasbey and mattison, boro council, tennis club, athletic club 22 clifton house, acession notes, ambler gazette, firefighting, east-end papers by Minnie Stewart Just 1 republcan, mary hough, history 23 faust tannery, historical society of montgomery county, Yerkes, Hovenden, ambler borough 1 clockmakers, conrad, ambler family, houpt, first presbyterian church, robbery, ordinance, McNulty, Mauchly, watershed 24 mattison, atkinson, directory, deeds 602 bethlehem pike, fire company, ambler borough 1 butler ave, downs-amey, william harmer will, mount pleasant baptist, St. Anthony fire, newt howard, ambler borough charter 25 colonial estates, hart tract, fchoolorest ave, talese, sheeleigh, opera house, ambler borough 1 golden jubilee, high s 26 mattison, asbestos, Newton Howard, Lindenwold, theatre, ambler theater, ambler/ambler borough 1 Dr. Reed, Mrs. Arthur Iliff, flute and drum, Duryea, St. Marys, conestoga, 1913 map, post office mural, public school, parade 27 street plan, mellon, Ditter, letter carriers, chamber of commerce, ambler ambler/ambler borough 1 directory 1928, Wiliam Urban, fife and drum, Wissahickon Fire Company, taprooms, prohibition, shoemaker, Jago, colony club, 28 charter, post cards, fire company, bridge, depot, library, methodist, church, ambler binder 1 colony club, fife and drum, bicentennial, biddle map, ambler park -

Notes and Queries Historical, Biographical, and Genealogical

3 Genet 1 Class BookE^^V \ VOLU M E Pi- Pennsylvania State Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https ://archive, org/details/ notesquerieshist00unse_1 .. M J L U Q 17 & 3 I at N . L3 11^ i- Ail ; ' ^ cu^,/ t ; <Uj M. 7 \ \ > t\ v .^JU V-^> 1 4 NOTES AXD QUERIES. and Mrs. Herman A1 ricks were born upon this land. David Cook, Sr., married a j Historical, Biographical and Geneal- Stewart. Samuel Fulton probably left i ogical. daughters. His executors were James Kerr and Ephraim Moore who resided LXL near Donegal church. Robert Fulton, the father of the in- Bcried in Maryland. — In Beard’s ventor who married Mary Smith, sister of Lutheran graveyard, Washington county, Colonel Robert Smith, of Chester county, Maryland, located about one-fourth of a was not of the Donegal family. There mile from Beard’s church, near Chews- seems to be two families of Fultons, and ville, stands an old time worn and dis- are certainly located in the wrong place, j colored tombstone. The following ap- Some of the descendants of Samuel Ful- pears upon its surface: ton move to the western part of Pennsyl- “Epitaphium of Anna Christina vania, and others to New York State. Geiserin, Born March 6, 1761, in the Robert Fulton, the father of the in- province of Pennsylvania, in Lancaster ventor, was a merchant tailor in Lancaster county. -

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 184 Margaret Cochran Corbin: Revolutionary Soldier Lead: During the Battle of Fort Washington in November, 1776

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 184 Margaret Cochran Corbin: Revolutionary Soldier Lead: During the Battle of Fort Washington in November, 1776 Molly Corbin fought the British as hard as any man. Intro.: "A Moment in Time" with Dan Roberts. Content: Margaret Corbin was a camp follower. At that time women were not allowed to join military units as combatants but most armies allowed a large number of women to accompany units on military campaigns. They performed tasks such as cleaning and cooking and due to their proximity to battle often got caught up in actual fighting. Mrs. Washington was a highly ranked camp follower. She often accompanied the General on his campaigns and was at his side during the dark winter of 1777 at Valley Forge. Many of these women were married, some were not and occasionally performing those rather dubious social duties associated with a large number of men alone far from home. Margaret Corbin was born on the far western frontier of Pennsylvania. Her parents were killed in an Indian raid and she was raised in the home of her uncle. In 1772 she married John Corbin who, at the outbreak of hostilities in 1776, enlisted in the First Pennsylvania Artillery. He was a matross (as in mattress), an assistant to a gunner. Margaret accompanied her husband having learned his duties when his unit was posted to Fort Washington on Manhattan Island near present day 183rd Street in New York City. They were assigned to a small gun battery at an outpost on Laurel Hill, northeast of the Fort on an out- cropping above the Harlem River. -

DIFFERENTIATING INSTRUCTION Economic Interference

CHAPTER 6 • SECTION 2 On March 5, 1770, a group of colo- nists—mostly youths and dockwork- ers—surrounded some soldiers in front of the State House. Soon, the two groups More About . began trading insults, shouting at each other and even throwing snowballs. The Boston Massacre As the crowd grew larger, the soldiers began to fear for their safety. Thinking The animosity of the American dockworkers they were about to be attacked, the sol- toward the British soldiers was about more diers fired into the crowd. Five people, than political issues. Men who worked on including Crispus Attucks, were killed. the docks and ships feared impressment— The people of Boston were outraged being forced into the British navy. Also, at what came to be known as the Boston many British soldiers would work during Massacre. In the weeks that followed, the their off-hours at the docks—increasing colonies were flooded with anti-British propaganda in newspapers, pamphlets, competition for jobs and driving down and political posters. Attucks and the wages. In the days just preceding the four victims were depicted as heroes Boston Massacre, several confrontations who had given their lives for the cause Paul Revere’s etching had occurred between British soldiers and of the Boston Massacre of freedom. The British soldiers, on the other hand, were portrayed as evil American dockworkers over these issues. fueled anger in the and menacing villains. colonies. At the same time, the soldiers who had fired the shots were arrested and Are the soldiers represented fairly in charged with murder. John Adams, a lawyer and cousin of Samuel Adams, Revere’s etching? agreed to defend the soldiers in court. -

Social Studies Vocabulary Chapter 8 Pages 268-291 20 Words Parliament-Britain's Law-Making Assembly

Social Studies Vocabulary Chapter 8 Pages 268-291 20 Words Parliament-Britain's law-making assembly. Stamp Act-law passed by Parliament in 1765 that taxed printed materials in the 13 Colonies. repeal-to cancel Sons of Liberty-groups of Patriots who worked to oppose British rule before the American Revolution. Townshend Acts-laws passed by Parliament in 1767 that taxed goods imported by the 13 Colonies from Britain. tariff-tax on imported goods. boycott-organized refusal to buy goods. Daughters of Liberty-groups of American women Patriots who wove cloth to replace boycotted British goods. Boston Massacre-event in 1770 in Boston which British soldiers killed five colonist who were part of an angry group that had surrounded them. Committee of Correspondence-groups of colonists formed in 1770's to spread news quickly about protests against the British. Tea Act-law passed by Parliament in the early 1770's stating that only the East India Company, a British business, could sell tea to the 13 Colonies. Boston Tea Party-Protests against British taxes in which the Sons of Liberty boarded British ships and dumped tea into Boston Harbor in 1773. Intolerable Acts-laws passed by British Parliament to punish the people of Boston following the Boston Tea Party. Patriots-American colonists who opposed British rule. Loyalists-colonists who remained loyal to the British during the American Revolution. First Continental Congress-meetings of representatives from every colony except Georgia held in Philadelphia in 1774 to discuss actions to take in response to the Intolerable Acts. militia-volunteer armies. minutemen-colonial militia groups that could be ready to fight at a minute's notice. -

American Revolution Vocabulary

American Revolution Vocabulary 1) abolish: To formally put an end to. 2) charter: A written document from a government or ruler that grants certain rights to an individual, group organization, or to people in general. In colonial times, a charter granted land to a person or a company along with the right to start a colony on that land. 3) committees of correspondence: Committees that began as voluntary associations and were eventually established by most of the colonial governments. Their mission was to make sure that each colony knew about events and opinions in the other colonies. They helped to unite the people against the British. 4) common good: The good of the community as a whole. 5) consent: To agree and accept something, approve of something, or allow something to take place. 6) Daughters of Liberty: An organization formed by women prior to the American Revolution. They got together to protest treatment of the colonies by their British rulers. They helped make the boycott of British trade effective by making their own materials instead of using British imports. 7) diplomacy: The practice of carrying on formal relationships with governments of other countries. 8) First Continental Congress: The body of colonial delegates who convened to represent the interests of the colonists and protest British rule. The First Continental Congress met in 1774 and drafted a Declaration of Rights. 9) Founders: The political leaders of the thirteen original colonies. They were key figures in the establishment of the United States of America. 10) government: The people and institutions with authority to make and enforce laws and manage disputes about laws.