Fall 2019 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obituary 1967

OBITUARY INDEX 1967 You can search by clicking on the binoculars on the adobe toolbar or by Pressing Shift-Control-F Request Form LAST NAME FIRST NAME DATE PAGE # Abbate Barbara F. 6/6/1967 p.1 Abbott William W. 9/22/1967 p.30 Abel Dean 11/27/1967 p.24 Abel Francis E. 9/25/1967 p.24 Abel Francis E. 9/27/1967 p.10 Abel Frederick B. 11/11/1967 p.26 Abel John Hawk 12/7/1967 p.42 Abel John Hawk 12/11/1967 p.26 Abel William E. 7/10/1967 p.28 Abel William E. 7/12/1967 p.12 Aber George W. 3/14/1967 p.24 Abert Esther F. 7/26/1967 p.14 Abrams Laura R. Hoffman 8/14/1967 p.28 Abrams Laura R. Hoffman 8/17/1967 p.28 Abrams Pearl E. 10/19/1967 p.28 Abrams Pearl E. 10/20/1967 p.10 Achenbach Helen S. 11/6/1967 p.36 Achenbach Helen S. 11/8/1967 p.15 Ackerman Calvin 5/22/1967 p.34 Ackerman Calvin 5/25/1967 p.38 Ackerman Fritz 11/27/1967 p.24 Ackerman Harold 10/27/1967 p.26 Ackerman Harold 10/28/1967 p.26 Ackerman Hattie Mann 4/14/1967 p.21 Ackerman Hattie Mann 4/19/1967 p.14 Adamczyk Bennie 5/3/1967 p.14 Adamo Margaret M. 3/15/1967 p.15 Adamo Margaret M. 3/20/1967 p.28 Adams Anna 6/17/1967 p.22 Adams Anna 6/20/1967 p.17 Adams Harriet C. -

T a Unacorrdda De Toros, Li.Ene Momen.To.S

LA PRIMERA AUTOPISTA IN TERNACIONAL DE ESPAÑA (A CCESO A MA DRID POR LA CARRETERA DE VALENCIA) ABIERTA AL TRAFICO UN AÑO ANTES DEL PLAZO PREVISTO Reflexiones ligeras antes de la gran' co rrida A fase i~e~alam~nleá.llle d()t a unacorrdda de toros, li.ene m om en.to.s de p.o"ItIVo mteres, aunqued~eUo,'i. no di.sfruteel público, lo que, Lgenéricamente, .se ha dado en llamar «Ia aficlón», So.D. Ios organiz.s;do. res, los empresarios, Ieaprotagorrístase interpretes d:e ese 'destajo previo, LQsq:ue tenell1Ósa ·nuestro cargo la función de regir los destinos de la Asociaoión de, La Prensa, tipo! couverrimoaen empreseríos taurinos una vez al año•.La entidad profesional r heriéric,a: de Ios periodiE.la$ .madzileños ha dado corrfdasdesd» casi inmedünamenle de'spuél>' de su funda ción, eu 1$95, Sólo hUho un paréntesis. - que no lo fue del todo--- con motivo de la guerra Civil. Lo s prufe-iouul"S ( )lit' nos haltúhalllo"', pa ra nu estra ven tu ru y '".a u rl ciad. e u la zona nac ional, :"t" II1iIllO'< (a p r ocupaci ón d e prepat ar la legada a J\ lad rid r lo mi smo q ue :'(: l' ltgi,', lllla Junta I i ruct iva para eucurgur se dCI znhiern» d e la Aso 'iac llill cuand o la cnpi lal lue ' 1; rcscntad u por las fu crzus na cro uu lc-, se hizo lo posib!e por 11 0 in te rru m p ir la trudic i ún y, upartu lItr o~ cs pecuieu los , se rlicron dos co rridus d e turos, unu ' 11 Zaruuozn )' ot ra 'm Hurgo:", Liberado i\la d r i(1. -

Dorothy Weir^Tawb "Dorothy L

Dorothy Weir^taWb "Dorothy L. Weir, 75, West Wheeling, Bellaire, died Saturday, Aug. 19, 1995, in East Ohio Regional Hospital at Martins Ferry. She was born Dec. 2, 1919 in Bridgeport, daughter of the late Thomas and Mary Butler Secrist. She was a Nazarene. She was preceded in death by her husband, Edward W. Weir; four brothers and three sisters. Surviving are a son, William Thomas Weir of Gnadenhutten; a daughter, Carol Lee Ramey of Mooresville, N.C.; a sister, Marie Pugh of Tucson, Ariz.; 10 grand children; four great-grandchildren. Friends will be received 2 to 4 and 7 to 9 p.m. today at the Bauknecht Funeral Home, Bellaire, where services will be held at 11 a.m. Tuesday, with the Rev. Michael Adkins officiating. Burial follows in Holly Memorial Gar dens, Pleasant Grove. a Edward yVe i r / i fi'f'UC / i 7 3 WEIR, Edward William, 75, of 67160 The Point, West Wheeling, Bellaire, died Friday in Ohio Valley Medical Center, Wheeling. He was a retired coal miner of Cravat Coal Co. and attended St. John Catholic Church, Bellaire. He was an Army veteran of World War II. He was preceded in death by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. William E. Weir. Surviving are his wife, Dorothy Sccrist Weir; a son, William T. of Gnadenhuttcn, Ohio; a daughter, Carol W. Ramey of Mooresville, N.C.; two sisters, Catherine White and Ann Rose, both of Bellaire; 10 grandchildren; two great-grandchil dren. Friends received 7-9 p.m. today and 2-4 and 7-9 p.m. -

Pdf (Boe-A-1990-5014

5656 Lunes 26 febrero 1990 BOE núm. 49 B. OPOSICIONES Y CONCURSOS tacta mediante certificación expedida por el órgano competente del MINISTERIO DE JUSTICIA Ministeno de Educación y Ciencia. c) Certi.ficado expedido por el Registro de Penados y Rebeldes. d) CertlÍicado médico acreditativo de no padecer enfermedad ni 5014 RESOLUCION de 19 defebrero de 1990, de la Subsecreta defecto físico q':le imposibilite para el ejercicio de la función, expedido r(a, por la que se hace pública la relación definitiva de por el Facultat,lvo de Medicina General de la Seguridad Social que aspirantes aprobados en. las· pruebas selectivas para ingreso corresponda al mteresado y, en caso de que no este acogido a cualquier en el Cuerpo de A.uxiliares-de la Administración de Justicia. régimen de la Seguridad Social, se expedirá por los Servicios Provincia turno libre. remitida por el Tribunal numero 1 de Madrid. les del Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, u Organismos correspondien tes de [as Comunidades Autónomas. Ilmo. Sr.: Concluido el plazo fijado en el apartado segundo del I;-os a~plrantes que tengan la condición de minusválidos presentarán Acuerdo de 28 de diciembre de 1989 ((Boletín Oficial del Estado» de 6 certlficactón de los órganos competentes del Ministerio de Trabajo y de enero de 1990). del" Tribunal numero 1 de Madrid. y resueltas las Seguridad Social que acredite tal condición y su capacidad para reclamaciones presentadas. dicho Tribunal ha propuesto a este Ministe desempeñar las funciones que corresponden al Cuerpo de Auxiliares de rio la relación definitiva de aspirantes que han superado las pruebas la Administración de Justicia. -

Catarrhcuredho- Yarns Tnn Arilla J

y Y t I II yr If i I vJ jf < y > r I t 1u 4 t 4il fr It d iA 4 I 1 I < I jII I I > t r JIo < l4- I 1 i o < 1 I J I t I VI II A I i i I T ifTij iaii I > X tN d fJtqL- utFiOOAS fGHT DEATH rxsitr 108f- Mkt YoddgloTet noutoq who tnn BHHBZH ORMEI MEET I l tt JEW + r- t Mfl11EESA UNttedglateeaityedareiCOaptltgetrt jail smite ttbo it t1iow U nde lloula I It IleMaaaget1V = bo ye pose r p t Wrecked ilpl Organ of VakI ci ltyFJnrli- manage their husbands stn better 4- 1- A Washtgtpn spacial e < we dtS Didive Do 1V r tiftBQ VhkZ hktDA- DIOnUILDIri COVRSE- 0 plostonandA OI3 tEctlEfipUlISlly SSrtiOYV < r Ir satlttAI- 1 13rgok I atternditii i they aveattfnpolittsba i Xe AltAlIS Itdl <nrHied1lrrynager- CllNSTEUCTION COLLAPSES wre th e AT OTjiXF OCEAN- it J l I lyn Life- x room l114 the l fm1 Xi pOl UILTnFrIOIUD- V7 J + t 21w joining on thepsinfldor of tb IMp V1iat Cuba r1efaMeaae to 8pahl itgL Ape at tho Poatoi1h at Craw The tlantago is enormous t oT ie- load qt Juba iwaame toSpain the Icwot ftrnteral VICTIMS IRE GRUSUEO BY DEBRIS WRECKED BY A F RIOUS STORM lotilvUlQlJ SOOU1l olass lUaU ulattor- entiro eastern part of the great th me1aenanHt1Ieli ii A teIMIJl < i<j her dddda people file marble pile + from main floor a tx min ttu II iiithe saute t9cbili r OtittYear In Advancp 01 On tb9 bt rral basement Is praott- ° meaneporrtae4btarvatlontt- 150donte- ueeltler Those 1Illeq El liteeoEtnployeii- wane WasUettirTowe t to Norfolk JiiV Ztian- yanttedy six j po pally a of ruina- I 7 otu Jltpel1fJahs L Syoro More ur gerloaiy eo- dFrom Cabs Crow ConstrlhY- tobo -

^UEVA ENTREVISTA RU8K - CASTIELLA Golpe De Estado

^UEVA ENTREVISTA RU8K - CASTIELLA Golpe de Estado «Estamos más adelantados que ayer» en la República Dominicana Su reinado viene siendo -declaró después el ministro español «una época de hechos Han sido derrocados por el mando militar y pensamientos», dice el presidente Bosch y su Gobierno «L'Osservatore Romano» Vueva Vork.—El ministro cs- Disolución de las dos Cámaras y proscripción legó ñol de Asuntos Exteriores, J8 í,ernando Alaría Castiella, del comunismp, castrismo y demás grupos extremista. í!" celebrado una segunda re- inion con el secretario de Es• Santo Domingo — El presidente Juan Bosch. de la República Dominicana, y su tado. Dean Kusk, cuando sola- Gobierno, han sido' derribados por un golpe militar, según ha informado un alto ofi• Lente faltan veinticuatro ho• cial del Gobierno. , « . • T ras para que expire el acuerdo El funcionario dijo que los dirigentes del golpe eran los generales Antonio Im-. hispano - norteamericano sobre bert y Luis Amiana, únicos supervivientes del grupo qúe atentó contra el presidente L bases conjuntas, con obje• Rafael Leónidas Trujillo. Agregó el funcionarlo que el golpe se produjo a las tres de to de llegar a una solución. la madrugada. ' .. jl^. ,. Después de la reunión del lu- De fuente autorizada se dice que el presidente y su Gobierno presentaron la di• Les, en los círculos norteame• misión anoche a consecuencia de la presión ejercida sobre el .presidente por oficiales ricanos se creía que el señor de alto rango, en el curso de una reunión mantenida la noche pasada en la base ae• Castiella no volvería a reunirse rea de San Isidro. -

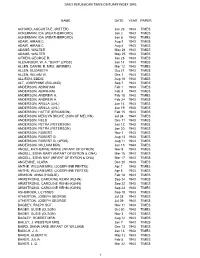

AKRON BEACON JOURNAL Index to Obituaries

AKRON BEACON JOURNAL Index to Obituaries 1962 - 1979 S Compiled by the staff of the Language, Literature and History Division, Akron-Summit County Public Library Name Date Saaffidi, Alice 3-3 1-70 Saal. Emma R. 2-3-67 Saal. Teresa 8-5-68 Saalfield. Arthur J. 4-1 3-78 Saalfield. Elizabeth R. 8-23-71 Saalfield. Hulda Jacobs 6-30-71 Saalfield. Margaret 9-2-68 Saalfield. Robert Sutton 3-1 8-63 Saari , mary C. 7-28-67 Saba, Frederick J. 5- 17-76 Sabad, James 12-28-65 Sabad. Rose 6-4-74 Sabados., Julia 4- 14-63 Sabat ino, Karen 9-30-68 Sabatino. Sara Louise 12-23-68 Sabek, Charles J. 2-28-66 Saber, Jeff 9-26-fi6 Sabetay, Evelyn S. 3-28-7Y Sabetay. Frances 10-25-71 Sabetay , Phoebe . 3-4-76 Sabetta, Arthur J. 1 1-26-76 Sabetta, William 9- 16-62 Sabin, Foster W. 7- I 9-78 Sabin, Hannah C. ’ 3-3-63 Sabin, Harriet 9- 18-62 Sabin, John : 1-20-74 Sabin, Leon li. 12-25-68 Sabine, Jennie 9-1 1-69 Sabino. Mary 9-4-79 Sabistina, Joseph 1-2-72 Sabistina. Theresa 7-1 1-74 Sable, Anna Rose 2-3-69 Sable, Joseph J. 7-20-65 Sablic, John F. 7- 12-63 Sabo. Anna 12-1 2-77 Sabo, Carrie T. 9-7-76 Sabo. Charles 9-6-63 Sabo, Dessie 11. 10-28-74 Sabo. Elizabeth 1-23-75 Sabo, Elizabeth T. 2-7-74 Sabo. Ellis 10-6-69 Sabo, Frank 8-9-75 Sabo, Gregory 3-27-69 Sabo, James 5-28-64 Sabo. -

OBIT 1943.Xlsx

DAILY REPUBLICAN TIMES OBITUARY INDEX 1943 NAME DATE YEAR PAPER ACHARD, AUGUSTA E. (RITTER) Jun 26 1943 TIMES ACKERMAN, IDA (WEATHERFORD) Jan 2 1943 TIMES ACKERMAN, IDA (WEATHERFORD) Jan 5 1943 TIMES ADAIR, HIRAM C. Aug 2 1943 TIMES ADAIR, HIRAM C. Aug 4 1943 TIMES ADAMS, WALTER May 24 1943 TIMES ADAMS, WALTER May 25 1943 TIMES AITKEN, GEORGE R. Jan 28 1943 TIMES ALEXANDER, W. A. "BURT" (2PGS) Jan 14 1943 TIMES ALLEN, DANIEL E. MRS. (BRINER) Mar 12 1943 TIMES ALLEN, ELIZABETH Oct 21 1943 TIMES ALLEN, WILIAM W. Dec 1 1943 TIMES ALLISON, EDDIE Aug 16 1943 TIMES ALT, JOSEPHINE (BOLAND) Sep 7 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ABRAHAM Feb 1 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ABRAHAM Feb 3 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ANDREW A. Feb 18 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ANDREW A. Feb 24 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ARILLA (UHL) Jun 14 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ARILLA (UHL) Jun 19 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, HATTIE (ERICKSON) Feb 15 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, MERLYN BRUCE (SON OF MELVIN) Jul 24 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, NELS Dec 11 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, PETRA (PETERSON) Jan 12 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, PETRA (PETERSON) Jan 20 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ROBERT Nov 1 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ROBERT G. Aug 13 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, ROBERT G. (2PGS) Aug 11 1943 TIMES ANDERSON, WILLIAM MRS. Jun 15 1943 TIMES ANGEL, KATHERINE MARIE (INFANT OF BYRON) Nov 9 1943 TIMES ANGELL, EDNA MARY (INFANT OF BYRON & ONA) Mar 15 1943 TIMES ANGELL, EDNA MAY (INFANT OF BYRON & ONA) Mar 17 1943 TIMES ANGEVINE, CLARA Dec 20 1943 TIMES ANTHE, WILLIAM MRS. (JOSEPHINE FERTIG) Apr 1 1943 TIMES ANTHE, WILLIAM MRS. -

Pdf (Boe-A-1978-49914

y con los emolumentos que, según liquidación reglamentaria, el 30 de septiembre de 1941, Profesor agregado de «Química le correspondan, de acuerdo con la Ley 31/1965, do 4 de Orgánica» de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad Autó mayo, sobre retribuciones de los Func.onarios de la Admi noma do Barcelona, con las condiciones establecidas en los nistración Civil del Estado y demás disposiciones complemen artículos 8.° y 9.° de la Ley 83/1965, de 17 de julio, sobre tarias. estructura de las Facultades Universitarias y su Profesorado, Lo digo a V. I. para su conocimiento y efectos. y con los emolumentos que, según liquidación reglamentaria, Dios guarde a V. I. muchos años. lo correspondan, de acuerdo con la Ley 31/1965, de 4. de Madrid, 23 de noviembre de 1977.—P. D-, el Director general mayo, sobre retribuciones de los Funcionarios de la Adminis de Universidades, Manuel Cobo del Rosall. tración Civil del Estado y demás disposiciones complemen tarias. Ilmo. Sr. Director general de Universidades. Lo digo a V. I. para su conocimiento y efectos. Dios guarde a-V. I. muchos años. Madrid, 25 de noviembre de 1977.—P. D., el-Director general de Universidades, Manuel Cobo del Rosal. ORDEN de 25 de noviembre de 1977 por la que Ilmo. Sr. Director general de Universidades. 768 se nombra a don Julio Delgado Martín Profesor agregado de «Química Orgánica» de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de La Laguna. Ilmo. Sr.: En virtud de concurso-oposición, ORDEN de 25 de noviembre de 1977 por la que Este Ministerio ha resuelto nombrar a don Julio Delgado 770 se nombra a don José Fuentes Mota Profesor agre Martín, número de Registro de Personal A42EC/1144, nacido gado de «Química Orgánica» de la Facultad de el ~12 de marzo de 1942, Profesor agregado de «Química Or Ciencias de la Universidad de Málaga. -

Copy of the Index

Index of Persons 407 (___) Jennie E. 131 Armour Cathleen Mary 335 Abby E. 151 Johanna E. 150 Abigail (Fales) 380 Colleen Ann 335 Abigail 81 , 98 Joyce 296 Abbot Cynthia Ann (Fales) 335 Almira L. 160 Judith 282 Mary E. 75 Dennis Michael 335 Ann (Gates) 155 Julia June 307 Abbott Lauren (Niblock) 335 Anna W. 264 Katherine 148 , 250 Lizzie S. 75 Marene Linda 335 Ardis 345 Kathy 238 , 303 Achard Margaret (Mole) 335 Avis 90 Kim 348 Albion G. 119 Mary Cobb8 (Edgarton) 177 Barbara 332 , 333 Kimberly Dawn 346 Bianca (Partridge) 119 Neva (Richard) 335 Barbara Jo 296 Laura 83 , 338 Lucy G. (Partridge) 119 Timothy George 335 Bernice 337 Leila 302 Ackerman William 335 Bettie 330 Leontyne 295 (___) 184 William John 335 Betty 340 , 365 Lois 383 Anna Vosler 238 Ahlstrom Bev 340 Louisa R. 87 Elizabeth (Concklin) 184 Lena 315 Beverly 333 Louise 241 Ella Rose7 (Shaw) 184 Albee Bill 155 Lydia 105 George Shaw8 184 , 238 Alice Vose8 175 Birdie 381 Margaret 107 Grace Marion (Keefe) 238 Anna (Briggs) 375 Bonnie 303 , 340 Margery 109 Jean Willis 238 Annie Laura (Hammond) 375 Carita 199 Marie 148 John Willis 184 , 238 Christopher Charles 376 Caroline 261 Marjorie H. 286 Louis 332 Colette (___) 376 Carrie B. 240 Marlene 333 Mary Michelle (Malone) 332 Courtney 376 Celia 161 Martha 136 , 340 Sara Elizabeth8 184 Doreen Elizabeth 376 Charles 176 Martha L. 237 Seth Padelford8 184 Edith Winifred 375 Charlotte Alice 311 Mary 146 , 287 , 297 , 368 Simeon 184 Edward 174 Chloe 31 Mary A. -

Bridgton Reporter Office Has Facllii!- >Od for Sale by S

/' nent ^VO LD on the Hill, to her ' Ò 5 , ìr customers ns to the SS, ÏBONS, *C. V O L . I . BRIDaTON, ME., FRIDAY, AUGUST 26, 1859. >rk K O . 4,2. ^ V C llO r it r other- Next winter you will chat with oth- withered face : that is a. comfort For us ty. Bat no ! do not let me say that—it is! husband. (Dinner’s the time to bring ’em! with them, but every skool boy nose PRESSED* nose our ka- J C r i ery; now and then, perhaps, I will be re- women to live after youth is passed, is not in my weakness itself that I should find home.) He sat down, said nothing, looked reer has been tremeniis OT;i Igs’ Store. IS PRINTEDPRrv-rcn EVERYfvvnv romFRIDAY i v MORNING BY I____1.. ., . ... i ... .... _ I ° ».vnaitiytremenjis. is. iuaYou nilwill excuse tf31 membered in the conversation, and some one living; that sorrow will be spared me. I strength ; for if I lose my philosophy and my j daggers, aDd pretended to quarrel with the me if 1 don't prase the erlv settlers of the S. H. NOYES, will say, »That poor Countess D. was a good will have had nothing but enjoyment Since ’ courage in facing death, I should lose it tenderest of tenderloins. The fact was how- Kobnies. People which hung idiotic old PUBLISHER ASD PROPRIETOR. little woman—very pretty, very gay; we the age of fifteen I have had three beautiful still more before wrinkled and gray hairs, ever, that he was preserving an enormous wimmin fur witches, burnt holes in Qurker’s BRIDGTON, ME. -

Roll of Successful Examinees in the NURSE LICENSURE EXAMINATION Held on DECEMBER 1 & 2, 2007 Released on FEBRUARY 20, 2008

Roll of Successful Examinees in the NURSE LICENSURE EXAMINATION Held on DECEMBER 1 & 2, 2007 Released on FEBRUARY 20, 2008 Roll of Successful Examinees in the NURSE LICENSURE EXAMINATION Held on DECEMBER 1 & 2, 2007 Page: 2 of 596 Released on FEBRUARY 20, 2008 Seq. No. N a m e 1 ABA, ADRIAN AGUILAR 2 ABA, LONI CASTILLON 3 ABAA, MARJORIE MENDOZA 4 ABABA, KHRISTHEA MAE SACRAMED 5 ABABAO, JOANNA ROSE MANA-AY 6 ABAC, FERMIN CATAQUIS 7 ABACHE, NELVIE DEJINO 8 ABAD, APRILROSE CERNA 9 ABAD, CIELO MAE DULINAYAN 10 ABAD, ELSA POJAS 11 ABAD, FRANCIS ARJELLE SANTOS 12 ABAD, JAKE VINCENT TABAY 13 ABAD, JAN RONALD ROMERO 14 ABAD, JENNIFER AMBAY 15 ABAD, JUANITA BLANCA FELICIANO 16 ABAD, JULIE ALBERT TAMAYO 17 ABAD, KATHLEEN EMIE TAN 18 ABAD, KENT FRANCIS NEGOSA 19 ABAD, KRISTINE MICHELLE SANTOS 20 ABAD, LESLIE JANE CACUT 21 ABAD, MA NICA BALISALISA 22 ABAD, MARIA CRISTINA CARI 23 ABAD, MARIA KRISABELLE GONZALES 24 ABAD, MARIANNE HAZEL BEÑAS 25 ABAD, MARK CHRISTIAN SANTOS 26 ABAD, MERALYN TAPON 27 ABAD, NESTER MANTILLA 28 ABAD, RACHELL ANN BIGLANG-AWA 29 ABAD SANTOS, JENA CLARISSE NUNAG 30 ABADA, CLARENCE ALFERI 31 ABADA, HENRY ALVAREZ 32 ABADAY, KIRSTIENNE HULAPONG 33 ABADIANO, CLARICE JUSTINIANI 34 ABADIANO, ROSANNA TORREVILLAS 35 ABADICIO, HADRIAN RIVAS 36 ABADIES, MARICEL CORRE 37 ABADILLA, AGNES RACAZA 38 ABADILLA, CARMICHELLE ORTIZ 39 ABADILLA, CRISTIANNE MARI AVERIA 40 ABADILLA, MARIA ODESSA JURIA 41 ABADOD, SHEENNA JUBELLE CABAY 42 ABAG, LUCILLE WALLACE 43 ABAGON, MARCHEL DEDAL 44 ABAINZA, CAMILLE ERICA ALDAY 45 ABAIS, IRENE SALUTAN 46 ABALDONADO, RACHEL GAPASIN 47 ABALES, FRANZ MACARILAY 48 ABALLE, ANIEWAY VERRA 49 ABALOS, GLENA MURIEL SUPAN 50 ABALOS, JOEL DE GUZMAN Roll of Successful Examinees in the NURSE LICENSURE EXAMINATION Held on DECEMBER 1 & 2, 2007 Page: 3 of 596 Released on FEBRUARY 20, 2008 Seq.