The Harmonious Conclusions of Peony Pavilion & the Lute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

From Story to Script: Towards a Morphology of the Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China

From Story to Script: towards a Morphology of The Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China Xiaohuan Zhao University of Otago, Donghua University This article is an attempt to analyze the dramatic structure of the Mudan ting 牡丹 亭 (Peony Pavilion) as a piece of fantasy which Tang Xianzu 湯顯祖 (1550–1616) created through the utilisation of structural devices and techniques of magic tales. The particular model adopted for the textual analysis is that formulated by Vladimir Propp in Morphology of Russian Folktale. This paper starts with a comparison of Russian magic tales Propp investigated for his morphological study and Chinese zhiguai 志怪 tales which provide the prototype for the Mudan ting with a view of justifying the application of the Proppian model. The second part of this paper is devoted to a critical review of the Proppian model and method in terms of function versus non-function, tale versus move, and character versus tale / theatrical role. Further information is also given in this part as a response to challenges and criticisms this article may incur as regards the applicability of the Proppian model in inter-cultural and inter-generic studies. Part Three is a morphological analysis of the dramatic text with a focus on the main storyline revolving around the hero and heroine. In the course of textual analysis, the particular form and sequence of functions is identified, the functional scheme of each move presented, and the distribution of dramatis personae in accordance with the sphere(s) of action of characters delineated. Finally this paper concludes with a presentation of the overall dramatic structure and strategy of this play. -

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES in CHINA by Hui Meng Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the Un

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA By Copyright 2012 Hui Meng Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa ________________________________ Misty Schieberle ________________________________ Jonathan Lamb Date Defended: April 3, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Hui Meng certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa Date approved: April 3, 2012 iii Abstract: Different from Germany, Japan and India, China has its own unique relation with Shakespeare. Since Shakespeare’s works were first introduced into China in 1904, Shakespeare in China has witnessed several phases of developments. In each phase, the characteristic of Shakespeare studies in China is closely associated with the political and cultural situation of the time. This thesis chronicles and analyzes noteworthy scholarship of Shakespeare studies in China, especially since the 1990s, in terms of translation, literary criticism, and performances, and forecasts new territory for future studies of Shakespeare in China. iv Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………1 Section 1 Oriental and Localized Shakespeare: Translation of Shakespeare’s Plays in China …………………………………………………………………... 3 Section 2 Interpretation and Decoding: Contemporary Chinese Shakespeare Criticism………………………………………………………………. -

Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China

Review of Educational Theory | Volume 02 | Issue 04 | October 2019 Review of Educational Theory https://ojs.bilpublishing.com/index.php/ret REVIEW Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China Yue Wang* The University of Milan, Milan, 20122, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Kunqu, literally means kun melody, is one of the most ancient forms of Received: 26 September 2019 Chinese opera. Originally her melody derives from Kunshan zone of Jiangsu province therefore it has been named Kunshan melody before, Revised: 15 October 2019 now Kunqu also known as Kunju, which means Kunqu opera. This paper Accepted: 21 October 2019 mainly focuses on the development of Kunqu in the past 100 years and the Published Online: 31 October 2019 influence of historical social and humanistic changes behind the special era on Kunqu, and compares the attitudes of scholars of different schools Keywords: of thought in different eras to Kunqu and the social public to compare and analyze the degree of love of Kunqu. Kunqu Last hundred years Development Inuence 1. Introduction opera have been developed on the basis of Kunqu. It is the most complete type of drama in the history of Chinese The original name of Kunqu is “tune of KunShan”, is opera, the biggest feature is the lyrical and delicate move- the ancient Chinese opera intonation type of drama, now ments, the combination of singing and dancing is inge- known as the “Kun drama”. Originated from the Yuan nious and harmonious ,in the costumes and make-up, the Dynasty (the middle of the 14th century), it’s a traditional generals have various kinds of costumes, the civil servants Chinese culture and art of the Han ethnic group. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

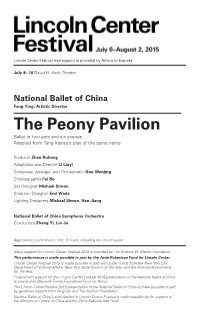

National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director the Peony Pavilion Ballet in Two Acts and Six Scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’S Play of the Same Name

07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 8 – 10 David H. Koch Theater National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director The Peony Pavilion Ballet in two acts and six scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’s play of the same name Producer Zhao Ruheng Adaptation and Director Li Liuyi Composer, Arranger, and Orchestrator Guo Wenjing Choreographer Fei Bo Set Designer Michael Simon Costume Designer Emi Wada Lighting Designers Michael Simon, Han Jiang National Ballet of China Symphony Orchestra Conductors Zhang Yi, Liu Ju Approximate performance time: 2 hours, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is made possible in part by generous support from Yang Lan and The Joelson Foundation. National Ballet of China’s participation in Lincoln Center Festival is made possible by the support of the Ministry of Culture of China and the China National Arts Fund. 07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 THE PEONY PAVILION July 8, 2015, at 8:00 p.m. -

How I Enjoyed the Peony Pavilion!

FEATURE How I Enjoyed The Peony Pavilion! By Chia-Hui Shih I enjoyed the performance of The Peony Pavilion so much that I wrote of my experiences with the show in two parts: first my overall impression as a layman and then my appreciation of the performance on each of the three days that the show lasted. Part I: A Layman’s Experience On September 22 to 24, I watched The Peony Pavilion at the Barclay Theater in Irvine, Calif. It was presented by a Chinese Kunqu opera company from Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Tang Xian Zu (the Ming Dynasty, 1550- 1616) wrote the libretti, originally consisting of 55 acts. I have never seen a Kunqu production, nor even heard any recital of Kunqu. My closer encounter with the play came some twenty years The melodies (if they could be called ago when I read a play written by Bai Xian Yong melodies, more like tones) in Kunqu are quite (the producer of The Peony Pavilion) named different from those in the popular Jingju (Peking “Visiting a Garden, Startled in a Dream”. It was Opera), are more monotonous—at least to the based on one episode of The Peony Pavilion. untrained ears of mine. On the other hand, the non-singing parts, such as the movement of eyes, hands, and arms; walking styles of men and women; and the dialogue were quite similar to those in Jingju. Actually I had expected that the spoken lines would be the dialect of Suzhou, but it turned out to be a mixture of Mandarin and some Jiangsu dialects, including that of Suzhou. -

READING BODIES: AESTHETICS, GENDER, and FAMILY in the EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE NOVEL GUWANGYAN (PREPOSTEROUS WORDS) by QING

READING BODIES: AESTHETICS, GENDER, AND FAMILY IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE NOVEL GUWANGYAN (PREPOSTEROUS WORDS) by QING YE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Qing Ye Title: Reading Bodies: Aesthetics, Gender, and Family in the Eighteenth Century Chinese Novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words) This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Maram Epstein Chairperson Yugen Wang Core Member Alison Groppe Core Member Ina Asim Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2016 ii © 2016 Qing Ye iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Qing Ye Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Languages and Literature June 2016 Title: Reading Bodies: Aesthetic, Gender, and Family in the Eighteenth Century Chinese Novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words) This dissertation focuses on the Mid-Qing novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words, preface dated, 1730s) which is a newly discovered novel with lots of graphic sexual descriptions. Guwangyan was composed between the publication of Jin Ping Mei (The Plum in the Golden Vase, 1617) and Honglou meng (Dream of the Red Chamber, 1791). These two masterpieces represent sexuality and desire by presenting domestic life in polygamous households within a larger social landscape. This dissertation explores the factors that shifted the literary discourse from the pornographic description of sexuality in Jin Ping Mei, to the representation of chaste love in Honglou meng. -

Masters of Chinese Literature - Tang Xianzu

Masters of Chinese Literature - Tang Xianzu Tang Xianzu, a native of Linchuan, Jiangxi, was born in 1550, the 29th year of the reign of Emperor Jiajing in the Ming Dynasty. He passed the provincial civil service examination at the age of 21, and the imperial examination at 34 obtaining the academic degree “Jinshi”. Over time he held official positions of “Taichang Boshi” (erudite in the Chamberlain for Ceremonials) and “Zhanshifu Zhubu” (secretary in the Supervisorate of Imperial Instruction), and up to “Libu Zhushi” (officer in the Ministry of Rites). In 1591, the 19th year of the reign of Emperor Wanli (grandson of Jiajing), he wrote “Memorial to Impeach the Ministers and Supervisors” in which he criticized the imperial government. Infuriated, the emperor banished him to the Xuwen County of Guangdong in Leizhou Peninsula, and demoted him to “Dianshi” (a low-level jail warden). On his way to Xuwen, he saw the Church of St. Paul. It is said that the church was originally a “warehouse-like structure built on planks and bricks”, located in the center of Macao. In his play “The Peony Pavilion”, Tang Xianzu deliberately referred to Catholicism in Macao as Buddhism, Western churches as Chinese temples, St. Paul as “Duobao” (a transliteration of St. Paul), and catholic priests as Buddhist monks and abbots to shun politics. Tang Xianzu, with such an unusual trip, made him the first to have reached the area of Macao before other famed Chinese literature masters. He wrote four seven-character quatrains, all of which depict the history and society of Macao in the period of Wanli, Ming Dynasty. -

On Wang Rongpei's Drama Translation Strategy

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 17, No. 3, 2018, pp. 28-34 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/10688 www.cscanada.org On Wang Rongpei’s Drama Translation Strategy: A Case Study of The Peony Pavilion CAO Shuo[a]; GAO Jingyang[b],*; JIANG Ying[b],* [a] Associate Professor. School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University Key words: The Peony Pavilion; Wang Rongpei; of Technology, Dalian, China. Translation strategy [b]School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China. *Corresponding author. Cao, S., Gao, J. Y., & Jiang, Y. (2018). On Wang Rongpei’s Drama Translation Strategy: A Case Study of The Peony Pavilion. Supported by Planning Fund of Social Sciences in Liaoning Province Studies in Literature and Language, 17(3), 28-34. Available (LI3DYY035). from: http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/sll/article/view/10688 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/10688 Received 22 September 2018; accepted 28 November 2018 Published online 26 December 2018 Abstract INTRODUCTION As a special literary form, drama is characterized by Kunqu Opera has a very high value of history, literature personalization, colloquialization, rhythm and the feature and art, embodying a rich aesthetic connotations and of performability. For a long time, the focus of drama profound cultural implications. During the development translation studies has also fallen on the “performability” of Kunqu Opera, the literati and artists crafted Kunqu at home and abroad. The Peony Pavilion is one of the Opera meticulously and learnt widely from other masterpieces in ancient China. With its beautiful and opera in instruments, vocal music, performances and elegant lyrics, engaging anecdotes and vivid characters, choreography, making it extremely popular in the The Peony Pavilion has an enduring popularity on the society. -

Passion, Romance, and Qing

iii Passion, Romance, and Qing The World of Emotions and States of Mind in Peony Pavilion By Tian Yuan Tan and Paolo Santangelo LEIDEN | BOSTON 9789004277670_Tan-Santangelo_text_proof-02.indb 3 8/20/2014 12:11:36 PM Preface Preface vii Preface Tang Xianzu explored the place of emotions in human experience in many of his writings. This is especially the case in his Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting) where we find a protracted meditation on love (qing). In our project, we attempt to adopt a multidisciplinary approach in analysing Tang’s Peony Pavilion through a systematic and detailed textual research based on ‘emotion words’ in the play. The research builds on the pioneering theoretical framework established by Santangelo (2003). Our collaboration has resulted in a database of 5,451 entries of ‘emotion words’ in Peony Pavilion, which is published as an extensive “Glos- sary” in this book. Further enquiries regarding the full electronic database (in simplified characters) with all entries can be made to the editors. The aim of the authors is to use Peony Pavilion as a case study to offer some material and broader reflections on the evolution and permanence of ‘emo- tions’ in Chinese culture focusing on but not restricted to this specific theatrical work. This volume intends to offer a contribution for scholars and readers who are interested in the legacy and vitality of this famous Ming dynasty drama by Tang Xianzu. Peony Pavilion reflects the new trends in the ‘cult of passions’ de- veloped at the end of the Ming dynasty. Its language is an attempt to express the new sensibility of the times, to improve the sentimental education, and to reflect the changing values of the society. -

The Peony Pavilion

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 232 4th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2018) Tension and Flow: an Analysis on the Emotional Structure of The Peony Pavilion Yanping Chen Collage of Literature and Journalism Sichuan University Chengdu, China 610064 Abstract—Influenced by the conditions of developed and even resonance. Through this subtle influence, readers commodities economy and Yang Ming philosophy of mind, receive irreplaceable emotional education. This is an there emerged a new wave of social thoughts focusing on emerging emotional concept that is different from traditional secularism and affirming human desire in the middle and late feudal ethics and is based on the affirmation of lust. It was Ming Dynasty. Tang Xianzu, who has fully absorbed the rejected and guarded by the feudal Guardian. In the 42nd essence of this emerging social thought trend, has involved it chapter of “A Dream of Red Mansions”, the secret warning into the legendary The Peony Pavilion in a creative way. This of Xue Baochai's warning to Lin Daiyu was the evidence, work, which affirms the desires of the secular people, has and she used the admonitory words: "I'm most afraid of stroked the dominant social concept with the core of Cheng being changed by miscellaneous book". It also proves that Zhu’s Neo-Confucianism in a very clear-cut manner. In the the book "The Peony Pavilion" shaped the temperament of works, this sharp contradiction is deeply expanded. The emotional tensions reflected in the development and evolution the girls in the Ming and Qing Dynasties.