THE TANCI FICTION JING ZHONG ZHUAN by YU ZHANG A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manchus: a Horse of a Different Color

History in the Making Volume 8 Article 7 January 2015 Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color Hannah Knight CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Knight, Hannah (2015) "Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color," History in the Making: Vol. 8 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol8/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color by Hannah Knight Abstract: The question of identity has been one of the biggest questions addressed to humanity. Whether in terms of a country, a group or an individual, the exact definition is almost as difficult to answer as to what constitutes a group. The Manchus, an ethnic group in China, also faced this dilemma. It was an issue that lasted throughout their entire time as rulers of the Qing Dynasty (1644- 1911) and thereafter. Though the guidelines and group characteristics changed throughout that period one aspect remained clear: they did not sinicize with the Chinese Culture. At the beginning of their rule, the Manchus implemented changes that would transform the appearance of China, bringing it closer to the identity that the world recognizes today. In the course of examining three time periods, 1644, 1911, and the 1930’s, this paper looks at the significant events of the period, the changing aspects, and the Manchus and the Qing Imperial Court’s relations with their greater Han Chinese subjects. -

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: the Great Qing and the Maritime World

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultüt der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Chung-yam PO Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kurtz Datum: 28 June 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgments 3 Emperors of the Qing Dynasty 5 Map of China Coast 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 43 Chapter 2 Modeling the Sea Space 62 Chapter 3 The Dragon Navy 109 Chapter 4 Maritime Customs Office 160 Chapter 5 Writing the Waves 210 Conclusion 247 Glossary 255 Bibliography 257 1 Abstract Most previous scholarship has asserted that the Qing Empire neglected the sea and underestimated the worldwide rise of Western powers in the long eighteenth century. By the time the British crushed the Chinese navy in the so-called Opium Wars, the country and its government were in a state of shock and incapable of quickly catching-up with Western Europe. In contrast with such a narrative, this dissertation shows that the Great Qing was in fact far more aware of global trends than has been commonly assumed. Against the backdrop of the long eighteenth century, the author explores the fundamental historical notions of the Chinese maritime world as a conceptual divide between an inner and an outer sea, whereby administrators, merchants, and intellectuals paid close and intense attention to coastal seawaters. Drawing on archival sources from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the West, the author argues that the connection between the Great Qing and the maritime world was complex and sophisticated. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

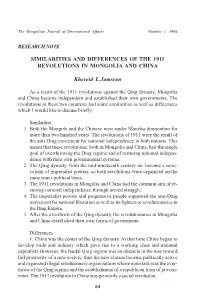

Similarities and Differences of the 1911 Revolutions in Mongolia and China

The Mongolian Journal of International Affairs Number 1, 1994 RESEARCH NOTE SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES OF THE 1911 REVOLUTIONS IN MONGOLIA AND CHINA Khereid L.Jamsran As a result of the 1911 revolutions against the Qing dynasty, Mongolia and China became independent and established their own governments. The revolutions in these two countries had some similarities as well as differences which 1 would like to discuss briefly. Similarities 1. Both the Mongols and the Chinese were under Manchu domination for more than two hundred years. The revolutions of 1911 were the result of the anti-Ding movement for national independence in both nations. This meant that these revolutions, both in Mongolia and China, had the single goal of overthrowing the Ding regime and of restoring national indepen- dence with their own governmental systems. 2. The Qing dynasty, from the mid-nineteenth century on, became a semi- colony of imperialist powers, so both revolutions were organized on the same souci-political basis. 3. The 1911 revolutions in Mongolia and China had the common aim of re- storing national independence through armed struggle. 4. The imperialist powers and progressive people supported the anti-Ding movement for national liberation as well as its fighters or revolutionaries in the Ding Empire. 5. After the overthrow of the Qing dynasty, the revolutionaries in Mongolia and China established their own forms of government. Differences 1. China was the center of the Qing dynasty. At that time China began to develop trade and industry which gave rise to a working class and national capitalists However, the feudal Qing regime was an obstacle in the way toward full prosperity of a new society, thus the new classes became politically active and organized illegal revolutionary organizations whose main task was the over- throw of the Qing regime and the establishment of a republican form of govern- ment. -

Exploring Counterfactuals in English and Chinese. Zhaoyi Wu University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1989 Exploring counterfactuals in English and Chinese. Zhaoyi Wu University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Wu, Zhaoyi, "Exploring counterfactuals in English and Chinese." (1989). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4511. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING COUNTERFACTUALS IN ENGLISH AND CHINESE A Dissertation Presented by ZHAOYI WU Submitted to the Graduate Schoo 1 of the University of Massachusetts in parti al fulfillment of the requirements for the deg ree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February, 1989 School of Education © Copyright by Zhaoyi Wu 1989 All Rights Reserved exploring counterfactuals IN ENGLISH AND CHINESE A Dissertation Presented by ZHAOYI WU Approved as to style and content by: S' s\ Je#£i Willett^ Chairperson oT Committee Luis Fuentes, Member Alfred B. Hudson, Member /V) (it/uMjf > .—A-- ^ ' 7)_ Mapdlyn Baring-Hidote, Dean School of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the help and suggestions given by professors of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and the active participation of Chinese students in the discussion of counterfactuals in English and Chinese. I am grateful to Dr. Jerri Willett for her recommendation of references to various sources of literature and her valuable comments on the manuscript. -

From Story to Script: Towards a Morphology of the Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China

From Story to Script: towards a Morphology of The Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China Xiaohuan Zhao University of Otago, Donghua University This article is an attempt to analyze the dramatic structure of the Mudan ting 牡丹 亭 (Peony Pavilion) as a piece of fantasy which Tang Xianzu 湯顯祖 (1550–1616) created through the utilisation of structural devices and techniques of magic tales. The particular model adopted for the textual analysis is that formulated by Vladimir Propp in Morphology of Russian Folktale. This paper starts with a comparison of Russian magic tales Propp investigated for his morphological study and Chinese zhiguai 志怪 tales which provide the prototype for the Mudan ting with a view of justifying the application of the Proppian model. The second part of this paper is devoted to a critical review of the Proppian model and method in terms of function versus non-function, tale versus move, and character versus tale / theatrical role. Further information is also given in this part as a response to challenges and criticisms this article may incur as regards the applicability of the Proppian model in inter-cultural and inter-generic studies. Part Three is a morphological analysis of the dramatic text with a focus on the main storyline revolving around the hero and heroine. In the course of textual analysis, the particular form and sequence of functions is identified, the functional scheme of each move presented, and the distribution of dramatis personae in accordance with the sphere(s) of action of characters delineated. Finally this paper concludes with a presentation of the overall dramatic structure and strategy of this play. -

Tibetan Written Images : a Study of Imagery in the Writings of Dhondup

Tibetan Written Images A STUDY OF IMAGERY IN THE WRITINGS OF DHONDUP GYAL Riika J. Virtanen Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 23rd of September, 2011 at 12 o'clock Publications of the Institute for Asian and African Studies 13 ISBN 978-952-10-7133-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-7134-8 (PDF) ISSN 1458-5359 http://ethesis.helsinki.fi Unigrafia Helsinki 2011 2 ABSTRACT Dhondup Gyal (Don grub rgyal, 1953 - 1985) was a Tibetan writer from Amdo (Qinghai, People's Republic of China). He wrote several prose works, poems, scholarly writings and other works which have been later on collected together into The Collected Works of Dhondup Gyal, in six volumes. He had a remarkable influence on the development of modern Tibetan literature in the 1980s. Exam- ining his works, which are characterized by rich imagery, it is possible to notice a transition from traditional to modern ways of literary expression. Imagery is found in both the poems and prose works of Dhondup Gyal. Nature imagery is especially prominent and his writings contain images of flowers and plants, animals, water, wind and clouds, the heavenly bodies and other en- vironmental elements. Also there are images of parts of the body and material and cultural images. To analyse the images, most of which are metaphors and similes, the use of the cognitive theory of metaphor provides a good framework for mak- ing comparisons with images in traditional Tibetan literature and also some images in Chinese, Indian and Western literary works. -

Curriculum Vitae for RICHARD L

Richard L. Davis, CV Curriculum Vitae for RICHARD L. DAVIS 戴仁柱 Office Department of History, Lingnan University Address: 302 Ho Sin Hang Bldg., Tuen Mun, NT Hong Kong tel. 852-2616-7007; fax 852-2467-7478 Home: Apt. G, F-18, Tower 1, 8 Waterloo Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong tel. 852-3486-2918 e-mail: [email protected] Date of Birth: April 12, 1951 Buffalo, New York, USA EDUCATION Ph.D.: 1980, Princeton University, East Asian Studies Department Major field of concentration: Tang-Song (A.D. 618-1279) political and cultural history (劉子健 James T.C. Liu, advisor) Minor fields of concentration: Yuan-Ming (A.D. 1271-1644) cultural history (Frederick W. Mote advisor) and modern Chinese politics (Lynn White III advisor) Dissertation: “The Shih Lineage at the Southern Sung Court: Aspects of socio-political mobility in Sung China” M.A.: 1977, Princeton University, East Asian Studies Department M.A.: 1975, State University of New York at Buffalo, History Department B.A.: 1973, State University of New York at Buffalo, Political Science and Asian Studies double major Non-degree Fall 1977-Spring 1979, Academia Sinica (Taipei), Institute of History Programs: & Philology, visiting research fellow 中央研究院/史語所 Summer 1973-Summer 1974, National Taiwan Normal University, 2 CV for Richard L. Davis Mandarin Training Center, post-graduate language training 國立台灣師範大學/國語中心 Summer 1976, Middlebury College, intensive Intermediate Japanese Summer 1972, Stanford University, intensive Classical Chinese Languages: Modern Chinese – fluency in reading and speaking Classical Chinese -

47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47

Vol 47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47 PLATEAU NARRATIVES 2017 Vol 47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47 E-MAIL: [email protected] HARD COPY: www.lulu.com/asianhp ONLINE: https://goo.gl/JycnYT ISSN (print): 1835-7741 ISSN (electronic): 1925-6329 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008944256 CALL NUMBER: DS1.A4739 SUBJECTS: Uplands-Asia-Periodicals, Tibet, Plateau of-Periodicals All artwork contained herein is subject to a Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. You are free to quote, copy, and distribute these works for non-commercial purposes so long as appropriate attribution is given. See https://goo.gl/nq06vg for more information. CITATION: Plateau Narratives 2017. 2017. Asian Highlands Perspectives 47. COVERS: Taken at a monastery in Rnga ba bod rigs dang chang rigs rang skyong khul (Aba zangzu qiangzu བབོདརིགསདངཆངརིགསརངོངལ zizhizhou 阿坝藏族羌族自治州 'Rnga ba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture'), Sichuan 四川 Province, China (2017, 'Jam dbyangs skyabs ). འཇམདངསབས 2 Vol 47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES Asian Highlands Perspectives (AHP ) is a trans-disciplinary journal focusing on the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding regions, including the Southeast Asian Massif, Himalayan Massif, the Extended Eastern Himalayas, the Mongolian Plateau, and other contiguous areas. The editors believe that cross-regional commonalities in history, culture, language, and socio-political context invite investigations of an interdisciplinary nature not served by current academic forums. AHP contributes to the regional research agendas of Sinologists, Tibetologists, Mongolists, and South and Southeast Asianists, while also forwarding theoretical discourse on grounded theory, interdisciplinary studies, and collaborative scholarship. AHP publishes occasional monographs and essay collections both in hardcopy (ISSN 1835-7741) and online (ISSN 1925-6329). -

Gutenberg Publishes the World's First Printed Book

Gutenberg Publishes the World's First Printed Book The exact date that Johannes Gutenberg published his first book - The Bible - isn't clear, although some historians believe the first section was published on September 30, 1452. The completed book - according to the Library of Congress - may have been released around 1455 or 1456. What is for sure is that Gutenberg's work, published on his printing press, changed the world. For the first time, books could be "mass produced" instead of "hand copied." It is believed that 48 originals, in various states of repair, still exist. The British Library has two copies - one printed on paper, the other on vellum (from the French word Vélin, meaning calf's skin) - and they can be viewed and compared online. The Bible, as Gutenberg published it, had 42 lines of text, evenly spaced in two columns: Gutenberg's Bible was a marvel of technology and a beautiful work of art. It was truly a masterpiece. The letters were perfectly formed, not fuzzy or smudged. They were all the same height and stood tall and straight on the page. The 42 lines of text were spaced evenly in two perfect columns. The large versals were bright, colorful and artistic. Some pages had more colorful artwork weaving around the two columns of text. (Johannes Gutenberg: Inventor of the Printing Press, by Fran Rees, page 67.) Did Gutenberg know how important his work would become? Most historians think not: Gutenberg must have been pleased with his handiwork. But he wouldn't have known then that this Bible would be considered one of the most beautiful books ever printed. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

An Analysis of Chao Jiong's Conception of the Three Teachings

chao jiong’s three teachings douglas skonicki Getting It for Oneself: An Analysis of Chao Jiong’s Conception of the Three Teachings and His Method of Self-Cultivation fter retiring from office in 1026, the Northern Song literatus Chao A 5Jiong 晁迥 (951–1034) chose to devote the remaining years of his life to reading, contemplation, and self-cultivation. Isolating himself within his family compound in the capital, Chao engaged in rigorous textual study, gymnastic exercises, and various forms of meditation that were designed to prolong his life, calm his mind, and facilitate his realization of the Dao. Chao eschewed rigid sectarianism and he utilized the teachings and practices of Buddhism, Daoism, and Con- fucianism to help him realize these objectives. Furthermore, he wrote about his post-retirement activities in detail, penning three separate texts in which he recorded his observations on the Three Teachings, the term traditionally used to refer to those three major practices, and their utility in furthering his efforts to cultivate the self. Chao’s texts — Zhaode xinbian 昭德新編 (New Compilation from Zhaode), Fazang suijin lu 法藏碎金錄 (Record of Golden Fragments from the Buddhist Canon), and Daoyuan ji 道院集 (The Daoist Cloister Collection) — contain a wealth of material on his conception of the Three Teachings and their methods of practice. As the most detailed and comprehensive literati statement on these matters surviving from the early Song, Chao’s works consti- tute an invaluable source for understanding early-Song approaches to the Three Teachings and self-cultivation. Yet, despite the intrinsic interest of these works and their po- tential to shed light on the early Song intellectual milieu, they have not attracted much scholarly attention.