From Story to Script: Towards a Morphology of the Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Parodies of Qing: Ironic Voices in Romantic Chuanqi Plays Yanbing Tan Washington University in St

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Summer 8-15-2018 Parodies of Qing: Ironic Voices in Romantic Chuanqi Plays Yanbing Tan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Tan, Yanbing, "Parodies of Qing: Ironic Voices in Romantic Chuanqi Plays" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1656. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1656 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures Program in Comparative Literature Dissertation Examination Committee: Robert E. Hegel, Chair Beata Grant Robert K. Henke Marvin Marcus Jamie Newhard Parodies of Qing: Ironic Voices in Romantic Chuanqi Plays by Yanbing Tan A dissertation presented -

Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies in Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Timothy Robert Clifford University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clifford, Timothy Robert, "In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2234. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 For more information, please contact [email protected]. In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Abstract The rapid growth of woodblock printing in sixteenth-century China not only transformed wenzhang (“literature”) as a category of knowledge, it also transformed the communities in which knowledge of wenzhang circulated. Twentieth-century scholarship described this event as an expansion of the non-elite reading public coinciding with the ascent of vernacular fiction and performance literature over stagnant classical forms. Because this narrative was designed to serve as a native genealogy for the New Literature Movement, it overlooked the crucial role of guwen (“ancient-style prose,” a term which denoted the everyday style of classical prose used in both preparing for the civil service examinations as well as the social exchange of letters, gravestone inscriptions, and other occasional prose forms among the literati) in early modern literary culture. This dissertation revises that narrative by showing how a diverse range of social actors used anthologies of ancient-style prose to build new forms of literary knowledge and shape new literary publics. -

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES in CHINA by Hui Meng Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the Un

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA By Copyright 2012 Hui Meng Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa ________________________________ Misty Schieberle ________________________________ Jonathan Lamb Date Defended: April 3, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Hui Meng certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa Date approved: April 3, 2012 iii Abstract: Different from Germany, Japan and India, China has its own unique relation with Shakespeare. Since Shakespeare’s works were first introduced into China in 1904, Shakespeare in China has witnessed several phases of developments. In each phase, the characteristic of Shakespeare studies in China is closely associated with the political and cultural situation of the time. This thesis chronicles and analyzes noteworthy scholarship of Shakespeare studies in China, especially since the 1990s, in terms of translation, literary criticism, and performances, and forecasts new territory for future studies of Shakespeare in China. iv Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………1 Section 1 Oriental and Localized Shakespeare: Translation of Shakespeare’s Plays in China …………………………………………………………………... 3 Section 2 Interpretation and Decoding: Contemporary Chinese Shakespeare Criticism………………………………………………………………. -

Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China

Review of Educational Theory | Volume 02 | Issue 04 | October 2019 Review of Educational Theory https://ojs.bilpublishing.com/index.php/ret REVIEW Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China Yue Wang* The University of Milan, Milan, 20122, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Kunqu, literally means kun melody, is one of the most ancient forms of Received: 26 September 2019 Chinese opera. Originally her melody derives from Kunshan zone of Jiangsu province therefore it has been named Kunshan melody before, Revised: 15 October 2019 now Kunqu also known as Kunju, which means Kunqu opera. This paper Accepted: 21 October 2019 mainly focuses on the development of Kunqu in the past 100 years and the Published Online: 31 October 2019 influence of historical social and humanistic changes behind the special era on Kunqu, and compares the attitudes of scholars of different schools Keywords: of thought in different eras to Kunqu and the social public to compare and analyze the degree of love of Kunqu. Kunqu Last hundred years Development Inuence 1. Introduction opera have been developed on the basis of Kunqu. It is the most complete type of drama in the history of Chinese The original name of Kunqu is “tune of KunShan”, is opera, the biggest feature is the lyrical and delicate move- the ancient Chinese opera intonation type of drama, now ments, the combination of singing and dancing is inge- known as the “Kun drama”. Originated from the Yuan nious and harmonious ,in the costumes and make-up, the Dynasty (the middle of the 14th century), it’s a traditional generals have various kinds of costumes, the civil servants Chinese culture and art of the Han ethnic group. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

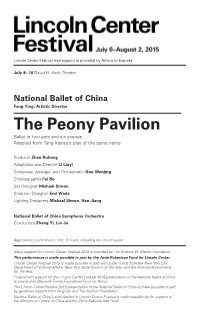

National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director the Peony Pavilion Ballet in Two Acts and Six Scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’S Play of the Same Name

07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 8 – 10 David H. Koch Theater National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director The Peony Pavilion Ballet in two acts and six scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’s play of the same name Producer Zhao Ruheng Adaptation and Director Li Liuyi Composer, Arranger, and Orchestrator Guo Wenjing Choreographer Fei Bo Set Designer Michael Simon Costume Designer Emi Wada Lighting Designers Michael Simon, Han Jiang National Ballet of China Symphony Orchestra Conductors Zhang Yi, Liu Ju Approximate performance time: 2 hours, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is made possible in part by generous support from Yang Lan and The Joelson Foundation. National Ballet of China’s participation in Lincoln Center Festival is made possible by the support of the Ministry of Culture of China and the China National Arts Fund. 07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 THE PEONY PAVILION July 8, 2015, at 8:00 p.m. -

How I Enjoyed the Peony Pavilion!

FEATURE How I Enjoyed The Peony Pavilion! By Chia-Hui Shih I enjoyed the performance of The Peony Pavilion so much that I wrote of my experiences with the show in two parts: first my overall impression as a layman and then my appreciation of the performance on each of the three days that the show lasted. Part I: A Layman’s Experience On September 22 to 24, I watched The Peony Pavilion at the Barclay Theater in Irvine, Calif. It was presented by a Chinese Kunqu opera company from Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Tang Xian Zu (the Ming Dynasty, 1550- 1616) wrote the libretti, originally consisting of 55 acts. I have never seen a Kunqu production, nor even heard any recital of Kunqu. My closer encounter with the play came some twenty years The melodies (if they could be called ago when I read a play written by Bai Xian Yong melodies, more like tones) in Kunqu are quite (the producer of The Peony Pavilion) named different from those in the popular Jingju (Peking “Visiting a Garden, Startled in a Dream”. It was Opera), are more monotonous—at least to the based on one episode of The Peony Pavilion. untrained ears of mine. On the other hand, the non-singing parts, such as the movement of eyes, hands, and arms; walking styles of men and women; and the dialogue were quite similar to those in Jingju. Actually I had expected that the spoken lines would be the dialect of Suzhou, but it turned out to be a mixture of Mandarin and some Jiangsu dialects, including that of Suzhou. -

Proquest Dissertations

TO ENTERTAIN AND RENEW: OPERAS, PUPPET PLAYS AND RITUAL IN SOUTH CHINA by Tuen Wai Mary Yeung Hons Dip, Lingnan University, H.K., 1990 M.A., The University of Lancaster, U.K.,1993 M.A., The University of British Columbia, Canada, 1999 A THESIS SUBIMTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 2007 @ Tuen Wai Mary Yeung, 2007 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-31964-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-31964-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

READING BODIES: AESTHETICS, GENDER, and FAMILY in the EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE NOVEL GUWANGYAN (PREPOSTEROUS WORDS) by QING

READING BODIES: AESTHETICS, GENDER, AND FAMILY IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE NOVEL GUWANGYAN (PREPOSTEROUS WORDS) by QING YE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Qing Ye Title: Reading Bodies: Aesthetics, Gender, and Family in the Eighteenth Century Chinese Novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words) This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Maram Epstein Chairperson Yugen Wang Core Member Alison Groppe Core Member Ina Asim Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2016 ii © 2016 Qing Ye iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Qing Ye Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Languages and Literature June 2016 Title: Reading Bodies: Aesthetic, Gender, and Family in the Eighteenth Century Chinese Novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words) This dissertation focuses on the Mid-Qing novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words, preface dated, 1730s) which is a newly discovered novel with lots of graphic sexual descriptions. Guwangyan was composed between the publication of Jin Ping Mei (The Plum in the Golden Vase, 1617) and Honglou meng (Dream of the Red Chamber, 1791). These two masterpieces represent sexuality and desire by presenting domestic life in polygamous households within a larger social landscape. This dissertation explores the factors that shifted the literary discourse from the pornographic description of sexuality in Jin Ping Mei, to the representation of chaste love in Honglou meng. -

Masters of Chinese Literature - Tang Xianzu

Masters of Chinese Literature - Tang Xianzu Tang Xianzu, a native of Linchuan, Jiangxi, was born in 1550, the 29th year of the reign of Emperor Jiajing in the Ming Dynasty. He passed the provincial civil service examination at the age of 21, and the imperial examination at 34 obtaining the academic degree “Jinshi”. Over time he held official positions of “Taichang Boshi” (erudite in the Chamberlain for Ceremonials) and “Zhanshifu Zhubu” (secretary in the Supervisorate of Imperial Instruction), and up to “Libu Zhushi” (officer in the Ministry of Rites). In 1591, the 19th year of the reign of Emperor Wanli (grandson of Jiajing), he wrote “Memorial to Impeach the Ministers and Supervisors” in which he criticized the imperial government. Infuriated, the emperor banished him to the Xuwen County of Guangdong in Leizhou Peninsula, and demoted him to “Dianshi” (a low-level jail warden). On his way to Xuwen, he saw the Church of St. Paul. It is said that the church was originally a “warehouse-like structure built on planks and bricks”, located in the center of Macao. In his play “The Peony Pavilion”, Tang Xianzu deliberately referred to Catholicism in Macao as Buddhism, Western churches as Chinese temples, St. Paul as “Duobao” (a transliteration of St. Paul), and catholic priests as Buddhist monks and abbots to shun politics. Tang Xianzu, with such an unusual trip, made him the first to have reached the area of Macao before other famed Chinese literature masters. He wrote four seven-character quatrains, all of which depict the history and society of Macao in the period of Wanli, Ming Dynasty. -

On Wang Rongpei's Drama Translation Strategy

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 17, No. 3, 2018, pp. 28-34 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/10688 www.cscanada.org On Wang Rongpei’s Drama Translation Strategy: A Case Study of The Peony Pavilion CAO Shuo[a]; GAO Jingyang[b],*; JIANG Ying[b],* [a] Associate Professor. School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University Key words: The Peony Pavilion; Wang Rongpei; of Technology, Dalian, China. Translation strategy [b]School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China. *Corresponding author. Cao, S., Gao, J. Y., & Jiang, Y. (2018). On Wang Rongpei’s Drama Translation Strategy: A Case Study of The Peony Pavilion. Supported by Planning Fund of Social Sciences in Liaoning Province Studies in Literature and Language, 17(3), 28-34. Available (LI3DYY035). from: http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/sll/article/view/10688 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/10688 Received 22 September 2018; accepted 28 November 2018 Published online 26 December 2018 Abstract INTRODUCTION As a special literary form, drama is characterized by Kunqu Opera has a very high value of history, literature personalization, colloquialization, rhythm and the feature and art, embodying a rich aesthetic connotations and of performability. For a long time, the focus of drama profound cultural implications. During the development translation studies has also fallen on the “performability” of Kunqu Opera, the literati and artists crafted Kunqu at home and abroad. The Peony Pavilion is one of the Opera meticulously and learnt widely from other masterpieces in ancient China. With its beautiful and opera in instruments, vocal music, performances and elegant lyrics, engaging anecdotes and vivid characters, choreography, making it extremely popular in the The Peony Pavilion has an enduring popularity on the society.