1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Founding Membership List

Founding Members of the Guardians of Culture Membership Group Institutions and Affiliated Organizations Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Alaska Native Language Archive Alcatraz Cruises Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. ASU American Indian Policy Institute Audrey and Harry Hawthorn Library and Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology Barona Cultural Center & Museum Caddo Heritage Museum Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Chickasaw Nation Cultural Center Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Dine College Dr. Fernando Escalante Community Library & Resource Center Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria George W. Brown Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center Hopi Tutuquyki Sikisve Huna Heritage Foundation International Buddhist Ethics Committee & Buddhist Tribunal on Human Rights Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma John G. Neihardt State Historic Site KCS Solutions, Inc. Maitreya Buddhist University Midwest Art Conservation Center Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Museo + Archivio, Inc. Museum Association of Arizona National Museum of the American Indian Newberry Library Noksi Press Osage Tribal Museum Papahana Kuaola Pawnee Nation College Pechanga Cultural Resources Department Poarch Creek Indians Quatrefoil Associates Chippewas of Rama First Nation Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute Speaking Place Tantaquidgeon Museum The Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University The Autry National Center of the American West The -

Cherokee Pottery

Ewf gcQl q<HhJJ Cherokee Pottery a/xW n A~ aGw People of One Fire D u n c a n R i g g s R o d n i n g Y a n t z ISBN: 0-9742818-2-4 Text by:Barbara Duncan, Brett H. Riggs, Christopher B. Rodning and I. Mickel Yantz, Design and Photography, unless noted: I. Mickel Yantz Copyright © 2007 Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc PO Box 515, Tahlequah, Oklahoma 74465 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage system or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Cover: Arkansas Applique’ by Jane Osti, 2005. Cherokee Heritage Center Back Cover: Wa da du ga, Dragonfly by Victoria McKinney, 2007; Courtesy of artist. Right: Fire Pot by Nancy Enkey, 2006; Courtesy of artist. Ewf gcQl q<HhJJ Cherokee Pottery a/xW n A~ aGw People of One Fire Dr. Barbara Duncan, Dr. Brett H. Riggs, Christopher B. Rodning, and I. Mickel Yantz Cherokee Heritage Center Tahlequah, Oklahoma Published by Cherokee Heritage Press 2007 3 Stamped Pot, c. 900-1500AD; Cherokee Heritage Center 2, Cherokee people who have been living in the southeastern portion of North America have had a working relationship with the earth for more than 3000 years. They took clay deposits from the Smokey Mountains and surrounding areas and taught themselves how to shape, decorate, mold and fire this material to be used for utilitarian, ceremonial and decorative uses. -

The Lost Arts Project - 1988

The Lost Arts Project - 1988 The Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. and the Cherokee Nation partnered in 1988 to create the Lost Arts Program focusing on the preservation and revival of cultural arts. A new designation was created for Master Craftsmen who not only mastered their art, but passed their knowledge on to the next generation. Stated in the original 1988 brochure: “The Cherokee people are at a very important time in history and at a crucial point in making provisions for their future identity as a distinct people. The Lost Arts project is concerned with the preservation and revival of Cherokee cultural practices that any be lost in the passage from one generation to another. The project is concerned with capturing the knowledge, techniques, individual commitment available to us and heritage received from Cherokee folk artists and developing educational and cultural preservation programs based on their knowledge and experience.” Artists had to be Cherokee and nominated by at least two people in the community. When selected, they were designated as “Living National Treasures.” 24 1 Do you know these Treasures? Lyman Vann - 1988 Bow Making Mattie Drum - 1990 Weaving Rogers McLemore - 1990 Weaving Hester Guess - 1990 Weaving Sally Lacy - 1990 Weaving Stella Livers - 1990 Basketry Eva Smith - 1991 Turtle Shell Shackles Betty Garner - 1993 Basketry Vivian Leaf Bush -1993 Turtle Shell Shackles David Neugin - 1994 Bow Making Vivian Elaine Waytula - 1995 Basketry Richard Rowe 1996 Carving Lee Foreman - 1999 Marble Making Original Lost Arts Program Exhibit Flyer- 1988 Mildred Justice Ketcher - 1999 Basketry Albert Wofford - 1999 Gig Making/Carving Willie Jumper - 2001 Stickball Sticks Sam Lee Still - 2002 Carving Linda Mouse-Hansen - 2002 Basketry Unfortunately, we have not been able to locate information, pictures or examples of art from the following Treasures. -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

Mountain Monsters Season 6 Episode 1 Free Download Mountain Monsters Season 6 Episode 1 Free Download

mountain monsters season 6 episode 1 free download Mountain monsters season 6 episode 1 free download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d97e1039bac41f • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Are We Ever Going To See a Mountain Monsters Season 6? Mountain Monsters is a show that has aired for five seasons on Destination America, one of the channels that’s frequently featured on premium packages for satellite and cable television. Typically, the network deals with things that are paranormal and in some cases, they venture into the world of cryptozoology. Mountain Monsters is a show that kind of combines both of these things into a single series, and people that have seen it either love it or hate it. It really is no middle ground with this show, to say the least. The show features the AIMS team and typically, you see them going out into the backwoods of the Appalachian Mountains looking for bigfoot or other storied cryptids that people have reported seeing. -

Guide to the Solomon Mccombs Papers, 1941-1974

Guide to the Solomon McCombs Papers, 1941-1974 Ioana Rates Summer 1976 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Correspondence, 1941-1974 (bulk 1946-1973)........................................ 4 Series 2: Lectures, unpublished writings, subject files, 1960-1973.......................... 5 Series 3: Miscellany................................................................................................. 6 Solomon McCombs Papers NAA.1974.0401 Collection Overview Repository: National Anthropological Archives Title: Solomon McCombs Papers Identifier: NAA.1974.0401 Date: 1941-1974 Extent: 2 Linear feet Creator: McCombs, Solomon, 1913-1980 (Creek) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information When he retired in 1974 to Tulsa, Oklahoma, Solomon McCombs, Creek Indian -

The Clemente Course in the Humanities;' National Endowment for the Humanities, 2014, Web

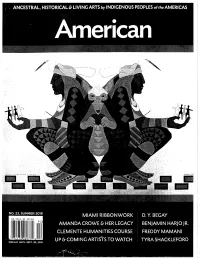

F1rstAmericanArt ISSUE NO. 23, SUMMER 2019 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Take a Closer Look: 24 Recent Developments 16 Four Emerging Artists By Mariah L. Ashbacher Shine in the Spotlight and America Meredith By RoseMary Diaz ( Cherokee Nation) (Santa Clara Tewa) Seven Directions 20 Amanda Crowe & Her Legacy: 30 By Hallie Winter (Osage Nation) Eastern Band Cherokee Art+ Literature 96 Woodcarving Suzan Shown Harjo By Tammi). Hanawalt, PhD By Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD peepankisaapiikahkia 36 Collections: 100 eehkwaatamenki aacimooni: The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Story of Miami Ribbonwork By Andrea L. Ferber, PhD By Scott M. Shoemaker, PhD Spotlight: Melt: Prayers 104 (Miami), George Ironstrack for the People and the Planet, (Miami), and Karen Baldwin Angela Babby (Oglala Lakota) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Reclaiming Space in Native 44 Calendar 109 Knowledges and Languages By Travis D. Day and America The Clemente Course Meredith (Cherokee Nation) in the Humanities By Laura Marshall Clark (Muscogee Creek) REVIEWS Exhibition Reviews 78 ARTIST PROFILES Book Review 94 D. Y.Begay: 54 Dine Textile Artist By Jennifer McLerran, PhD IN MEMORIAM Benjamin Harjo Jr.: 60 Joe Fafard, OC, SOM (Melis) 106 Absentee Shawnee/Seminole Painter By Gloria Bell, PhD (Metis) and Printmaker Frank LaPefta 107 By Staci Golar (Nomtipom Maidu) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Freddy Mamani Silvestre: 66 Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk) Aymara Architect By jean Merz-Edwards By Vivian Zavataro, PhD Tyra Shackleford: 72 Chickasaw Textile Artist By Vicki Monks (Chickasaw) COVER Benjamin Harjo 'Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/ Seminole), creator and coyote compete to make man, 2016, gouache on Arches watercolor paper, 20 x 28 in., private collection. -

Cherokee-English Machine Translation for Endangered Language Revitalization

ChrEn: Cherokee-English Machine Translation for Endangered Language Revitalization Shiyue Zhang Benjamin Frey Mohit Bansal UNC Chapel Hill {shiyue, mbansal}@cs.unc.edu; [email protected] Abstract Src. ᎥᏝ ᎡᎶᎯ ᎠᏁᎯ ᏱᎩ, ᎾᏍᎩᏯ ᎠᏴ ᎡᎶᎯ ᎨᎢ ᏂᎨᏒᎾ ᏥᎩ. Ref. They are not of the world, even as I am not of the Cherokee is a highly endangered Native Amer- world. ican language spoken by the Cherokee peo- SMT It was not the things upon the earth, even as I am ple. The Cherokee culture is deeply embed- not of the world. ded in its language. However, there are ap- NMT I am not the world, even as I am not of the world. proximately only 2,000 fluent first language Table 1: An example from the development set of Cherokee speakers remaining in the world, and ChrEn. NMT denotes our RNN-NMT model. the number is declining every year. To help save this endangered language, we introduce people: the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians ChrEn, a Cherokee-English parallel dataset, to (EBCI), the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee facilitate machine translation research between Indians (UKB), and the Cherokee Nation (CN). Cherokee and English. Compared to some pop- ular machine translation language pairs, ChrEn The Cherokee language, the language spoken by is extremely low-resource, only containing 14k the Cherokee people, contributed to the survival sentence pairs in total. We split our paral- of the Cherokee people and was historically the ba- lel data in ways that facilitate both in-domain sic medium of transmission of arts, literature, tradi- and out-of-domain evaluation. -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE REPRESENTATION AND MISREPRESENTATION: DEPICTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN OKLAHOMA POST OFFICE MURALS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By DENISE NEIL-BINION Norman, Oklahoma 2017 REPRESENTATION AND MISREPRESENTATION: DEPICTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN OKLAHOMA POST OFFICE MURALS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY ______________________________ Dr. Mary Jo Watson, Chair ______________________________ Dr. W. Jackson Rushing III ______________________________ Mr. B. Byron Price ______________________________ Dr. Alison Fields ______________________________ Dr. Daniel Swan © Copyright by DENISE NEIL-BINION 2017 All Rights Reserved. For the many people who instilled in me a thirst for knowledge. Acknowledgements I wish to extend my sincerest appreciation to my dissertation committee; I am grateful for the guidance, support, and mentorship that you have provided me throughout this process. Dr. Mary Jo Watson, thanks for being a mentor and a friend. I also must thank Thomas Lera, National Postal Museum (retired) and RoseMaria Estevez of the National Museum of the American Indian. The bulk of my inspiration and research developed from working with them on the Indians at the Post Office online exhibition. I am also grateful to the Smithsonian Office of Fellowships and Internships for their financial support of this endeavor. To my friends and colleagues at the University of Oklahoma, your friendship and support are truly appreciated. Tammi Hanawalt, heather ahtone, and America Meredith thank you for your encouragement, advice, and most of all your friendship. To the 99s Museum of Women Pilots, thanks for allowing me so much flexibility while I balanced work, school, and life. -

To Download Information Packet

INFORMATION PACKET General Information • Important Dates in Cherokee History • The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Tribal Government • Cherokee NC Fact Sheet • Eastern Cherokee Government Since 1870 • The Cherokee Clans • Cherokee Language • The Horse/Indian Names for States • Genealogy Info • Recommended Book List Frequently Asked Questions—Short ResearCh Papers with References • Cherokee Bows and Arrows • Cherokee Clothing • Cherokee Education • Cherokee Marriage Ceremonies • Cherokee Villages and Dwellings in the 1700s • Thanksgiving and Christmas for the Cherokee • Tobacco, Pipes, and the Cherokee Activities • Museum Word Seek • Butterbean Game • Trail of Tears Map ArtiCles • “Let’s Put the Indians Back into American History” William Anderson Museum of the Cherokee Indian Info packet p.1 IMPORTANT DATES IN CHEROKEE HISTORY Recently, Native American artifacts and hearths have been dated to 17,000 B.C. at the Meadowcroft site in Pennsylvania and at Cactus Hill in Virginia. Hearths in caves have been dated to 23,000 B.C. at sites on the coast of Venezuela. Native people say they have always been here. The Cherokee people say that the first man and first woman, Kanati and Selu, lived at Shining Rock, near present-day Waynesville, N.C. The old people also say that the first Cherokee village was Kituwah, located around the Kituwah Mound, which was purchased in 1997 by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to become once again part of tribal lands. 10,000 BC-8,000 BC Paleo-Indian Period: People were present in North Carolina throughout this period, making seasonal rounds for hunting and gathering. Continuous occupation from 12,000 BC has been documented at Williams Island near Chattanooga, Tennessee and at some Cherokee town sites in North Carolina, including Kituhwa and Ravensford. -

1Ce1o039p 959426.Pdf

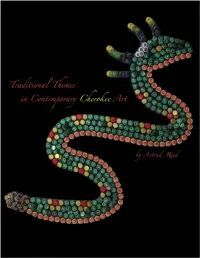

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword I have always taken issue with the idea that the word “myth” has come to signify falsehood. I don’t want to get into a discussion here on the nuances and subtleties of language, but the idea that a culture can be judged simplistic and primitive based upon its myths has always concerned me. After all, what is myth? Creation stories, talk stories, foundations of culture, foundations of language, the basis from which all social and cultural definitions come forth and define a people, a language, a system of belief, a way of knowing, a way of being. Therefore, creation stories that are not literal creation stories are the idea that a culture can be judged simplistic and primitive based upon its myths has always concerned me. -

Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE)

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: Cherokee (ch Eh – ruh – k EE) Nation Tribal website(s): http//www.cherokee.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” • The Cherokees are original residents of the American southeast region, particularly Georgia, North and South Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Most Cherokees were forced to move to Oklahoma in the 1800's along the Trail of Tears. Descendants of the Cherokee Indians who survived this death march still live in Oklahoma today. Some Cherokees escaped the Trail of Tears by hiding in the Appalachian hills or taking shelter with sympathetic white neighbors. The descendants of these people live scattered throughout the original Cherokee Indian homelands. After the Civil War more a new treaty allowed the government to dispose of land in the Cherokee Outlet. The settlement of several tribes in the eastern part of the Cherokee Outlet (including the Kaw, Osage, Pawnee, Ponca, and Tonkawa tribes) separated it from the Cherokee Nation proper and left them unable to use it for grazing or hunting.