Doctoral Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS 7536 Pochoir Prints of Ledger Drawings by the Kiowa Five

MS 7536 Pochoir prints of ledger drawings by the Kiowa Five National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Local Numbers................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical................................................................................................... -

![The Story of the Taovaya [Wichita]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0725/the-story-of-the-taovaya-wichita-20725.webp)

The Story of the Taovaya [Wichita]

THE STORY OF THE TAOVAYA [WICHITA] Home Page (Images Sources): • “Coahuiltecans;” painting from The University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts; www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/peoples/coahuiltecans.html • “Wichita Lodge, Thatched with Prairie Grass;” oil painting on canvas by George Catlin, 1834-1835; Smithsonian American Art Museum; 1985.66.492. • “Buffalo Hunt on the Southwestern Plains;” oil painting by John Mix Stanley, 1845; Smithsonian American Art Museum; 1985.66.248,932. • “Peeling Pumpkins;” Photogravure by Edward S. Curtis; 1927; The North American Indian (1907-1930); v. 19; The University Press, Cambridge, Mass; 1930; facing page 50. 1-7: Before the Taovaya (Image Sources): • “Coahuiltecans;” painting from The University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts; www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/peoples/coahuiltecans.html • “Central Texas Chronology;” Gault School of Archaeology website: www.gaultschool.org/history/peopling-americas-timeline. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • Terminology Charts from Lithics-Net website: www.lithicsnet.com/lithinfo.html. Retrieved January 17, 2018. • “Hunting the Woolly Mammoth;” Wikipedia.org: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hunting_Woolly_Mammoth.jpg. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • “Atlatl;” Encyclopedia Britannica; Native Languages of the Americase website: www.native-languages.org/weapons.htm. Retrieved January 19, 2018. • “A mano and metate in use;” Texas Beyond History website: https://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/kids/dinner/kitchen.html. Retrieved January 18, 2018. • “Rock Art in Seminole Canyon State Park & Historic Site;” Texas Parks & Wildlife website: https://tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/seminole-canyon. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • “Buffalo Herd;” photograph in the Tales ‘N’ Trails Museum photo; Joe Benton Collection. A1-A6: History of the Taovaya (Image Sources): • “Wichita Village on Rush Creek;” Lithograph by James Ackerman; 1854. -

Founding Membership List

Founding Members of the Guardians of Culture Membership Group Institutions and Affiliated Organizations Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Alaska Native Language Archive Alcatraz Cruises Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. ASU American Indian Policy Institute Audrey and Harry Hawthorn Library and Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology Barona Cultural Center & Museum Caddo Heritage Museum Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Chickasaw Nation Cultural Center Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Dine College Dr. Fernando Escalante Community Library & Resource Center Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria George W. Brown Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center Hopi Tutuquyki Sikisve Huna Heritage Foundation International Buddhist Ethics Committee & Buddhist Tribunal on Human Rights Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma John G. Neihardt State Historic Site KCS Solutions, Inc. Maitreya Buddhist University Midwest Art Conservation Center Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Museo + Archivio, Inc. Museum Association of Arizona National Museum of the American Indian Newberry Library Noksi Press Osage Tribal Museum Papahana Kuaola Pawnee Nation College Pechanga Cultural Resources Department Poarch Creek Indians Quatrefoil Associates Chippewas of Rama First Nation Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute Speaking Place Tantaquidgeon Museum The Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University The Autry National Center of the American West The -

The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture by Victoria Grieve (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009

REVIEWS 279 within a few years of reaching its previously excluded sectors of socie - height. McVeigh finds that infighting, ty. Their work is harder, as the popu - bad press, and political missteps prior lations they represent are usually to the 1924 presidential election all oppressed and thus have less access contributed to the Klan’s decline. By to financial and other resources to 1928, only a few hundred thousand fund their battles. These clear differ - members remained in the group. ences argue strongly for separate In a larger context, McVeigh’s analyses of social movements from work makes a strong case for why the right and the left. conservative and liberal social move - ments should be treated differently. HEIDI BEIRICH , who graduated from McVeigh rightly points out that con - Purdue University with a Ph.D. in servative social movements offer political science, is director of remedies for populations that have research for the Southern Poverty Law power, but believe they are being Center. She is the co-editor of Neo- challenged by changes in society. Confederacy: A Critical Introduction Because of this established power, (2008). social movements from the right tend to bring greater resources to bear on KEVIN HICKS , who graduated from their causes. Liberal social move - Purdue University with a Ph.D. in ments, on the other hand, look to English, is associate professor of Eng - expand opportunities and rights to lish at Alabama State University. The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture By Victoria Grieve (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009. Pp. x, 299. -

2017 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Meeting in Columbus, Ohio October 25th-28th, 2017 Conference Chair, Aaron Petten, Columbus College of Art & Design Emma Abercrombie, SCAD Savannah The Millennial and the Millennial Female: Amalia Ulman and ORLAN This paper focuses on Amalia Ulman’s digital performance Excellences and Perfections and places it within the theoretical framework of ORLAN’s surgical performance series The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan. Ulman’s performance occurred over a twenty-one week period on the artist’s Instagram page. She posted a total of 184 photographs over twenty-one weeks. When viewed in their entirety and in relation to one another, the photographs reveal a narrative that can be separated into three distinct episodes in which Ulman performs three different female Instagram archetypes through the use of selfies and common Instagram image tropes. This paper pushes beyond the casual connection that has been suggested, but not explored, by art historians between the two artists and takes the comparison to task. Issues of postmodern identity are explored as they relate to the Internet culture of the 1990s when ORLAN began her surgery series and within the digital landscape of the Web 2.0 age that Ulman works in, where Instagram is the site of her performance and the selfie is a medium of choice. Abercrombie situates Ulman’s “image-body” performance within the critical framework of feminist performance practice, using the postmodern performance of ORLAN as a point of departure. J. Bradley Adams, Berry College Controlled Nature Focused on gardens, Adams’s work takes a range of forms and operates on different scales. -

George Tooker David Zwirner

David Zwirner New York London Hong Kong George Tooker Artist Biography George Tooker (1920–2011) is best known for his use of the traditional, painstaking medium of egg tempera in compositions reflecting urban life in American postwar society. Born in Brooklyn, he received a degree in English from Harvard University before he began his studies at the Art Students League in 1943, where he worked under the regionalist painter Reginald Marsh. In 1944, Tooker met the artist Paul Cadmus, and they soon became lovers. Cadmus, sixteen years his senior, introduced Tooker to the artist Jared French, with whom he was romantically involved, and French’s wife, Margaret Hoening French, and the four of them traveled extensively throughout Europe and vacationed regularly together. Tooker appears in a number of the photographs taken by PaJaMa, the photographic collective formed by Cadmus and the Frenches, and he served as a model for Cadmus’s painting Inventor (1946). Cadmus and French introduced Tooker to the time-intensive medium of egg tempera, which would become his principal medium. Tooker’s career found early success, due in part to his friend Lincoln Kirstein, the co-founder of the New York City Ballet, encouraging the inclusion of his work in the Fourteen Americans (1946) and Realists and Magic-Realists (1950) exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art. In 1950, Subway (1950) entered the Whitney Museum of American Art’s collection—the artist’s first museum acquisition—and the following year he received his first solo exhibition at the Edwin Hewitt Gallery. Near the end of the 1940s, Tooker parted ways with Cadmus because of the latter’s ongoing relationship with the Frenches. -

1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

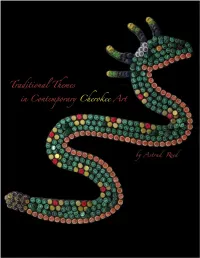

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword "What About Indian Art?" An Interview with Dr. Mary Jo Watson Director, School of Art and Art History / Regents Professor of Art History KGOU Radio Interview by Brant Morrell • April 17, 2013 Twenty years ago, a degree in Native American Art and Art History was non-existent. Even today, only a few universities offer Native Art programs, but at the University of Oklahoma Mary Jo Watson is responsible for launching a groundbreaking art program with an emphasis on the indigenous perspective. You expect a director of an art program at a major university to have pieces in their office, but entering Watson’s workspace feels like stepping into a Native art museum. -

Bacone College COVID Policy 0262021 Update FINAL

August 26, 2021 Greetings from Bacone College! We are excited to welcome all students and employees back to campus for the 2021 Fall Semester. As we begin this new school year, it is Bacone College’s goal to promote health and safety in our learning and working environments so that our students can remain in full-time, in-person learning. To accomplish this goal, Bacone College’s President, Dr. Ferlin Clark, has determined it is necessary to implement the COVID-19 Policy attached hereto. While COVID vaccinations became available earlier this year—ensuring greater protections for those who choose to get vaccinated—the Delta variant of COVID-19 has significantly increased rates of transmission and serious illness for those who remain unvaccinated. Currently, 85% of Bacone College’s employees are fully vaccinated, however, only 25% of Bacone’s students are fully vaccinated. The low rate of vaccination among our student body, coupled with the current increase in Delta variant COVID cases, increases the likelihood that Bacone will have to adopt a stricter Policy at some point in the future, including, but not limited to, a potential move back to remote learning. In an effort to avoid more drastic measures, the attached COVID-19 Policy provides basic prevention strategies aimed at keeping our College community, as well as the surrounding communities and the tribal communities many of our students call home, safe and healthy. Bacone College’s Fall 2021 COVID-19 Policy builds upon the Medicine Wheel framework that guided our previous COVID-19 policies. Our Medicine Wheel framework is a circular, cyclical concept that is unending. -

FALL 2017 Dream Bigger

President’s Report FALL 2017 WWW.MACU.EDU Dream Bigger. Do Greater. WHAT’S INSIDE 3 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 4 - 5 2016-2017 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Mid-America Christian University 3500 SW 119th Street 6 -11 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73170 DONOR HONOR ROLL 405-691-3800 www.MACU.edu 12 President DREAM SCHOLARSHIP GALA Dr. John Fozard ALUMNI DISCOUNT Editors Jody Allen 13 Whitney K. Knight IRON MEN Elizabeth Sieg WOMEN OF VALOR Photos/Images: Andy Marks, Grandeur Photography, LLC Frankie Heath 14 Michele LaVasque Photography M-CORE Do You Have an Alumni Update or Story Idea? PLEASE SEND IT TO 15 [email protected] STUDENT SPOTLIGHT 16-17 ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT MID-AMERICA 18-19 CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY FACULTY SPOTLIGHT 20 CHAPEL PREVIEW @MACHRISTIANUNIV 21 EDUCATION UPDATES 2 2 -2 3 @MACU SPORTS UPDATE 24 MACU GOLF CLASSIC SCHOOL OF WESLEYAN STUDIES MACU.EDU/WATCH WATCH MACU CHAPEL LIVE DURING THE 25 SCHOOL YEAR EVERY WEDNESDAY AND FACULTY SPOTLIGHT FRIDAY AT 10 A.M. COVER PHOTO 26 Kennedy Hall on the MACU campus EVANGEL FUND TABLE OF CONTENTS PHOTO 27 MACU students take a study break between classes 2 | MID-AMERICAN ETERNAL FALL INVESTMENT 2017 A LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friends, Travelers in ancient times were accustomed to ask local to spend time with the past when we can hardly keep people the way to a destination. In the more remote pace with the present, let alone the future? Do we really landscapes and mountainous terrains, travelers often need “Ebenezers?” Do mile markers serve any purpose lost their way and in hazardous weather, they lost their other than to mark our pathway to the present? lives. -

Oral History Interview with Paul Cadmus, 1988 March 22-May 5

Oral history interview with Paul Cadmus, 1988 March 22-May 5 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Paul Cadmus on March 22, 1988. The interview took place in Weston, Connecticut, and was conducted by Judd Tully for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview JUDD TULLY: Tell me something about your childhood. You were born in Manhattan? PAUL CADMUS: I was born in Manhattan. I think born at home. I don't think I was born in a hospital. I think that the doctor who delivered me was my uncle by marriage. He was Dr. Brown Morgan. JUDD TULLY: Were you the youngest child? PAUL CADMUS: No. I'm the oldest. I's just myself and my sister. I was born on December 17, 1904. My sister was born two years later. We were the only ones. We were very, very poor. My father earned a living by being a commercial lithographer. He wanted to be an artist, a painter, but he was foiled. As I say, he had to make a living to support his family. We were so poor that I suffered from malnutrition. Maybe that was the diet, too. I don't know. I had rickets as a child, which is hardly ever heard of nowadays. -

2017 Csfl News Release

2017 CSFL NEWS RELEASE Ryan Hintergardt, CSFL Sports Information Director [email protected] 2017 CENTRAL STATES FOOTBALL LEAGUE RELEASES ALL-LEAGUE TEAMS November 20, 2017 - The Central States Football League (CSFL) has announced the All-CSFL selections for the 2017 season. A first-team, second-team and honorable mention team are listed below along with Players of the Year and Coach of the Year. The CSFL is comprised of Arizona Christian University, Bacone College, Langston University, Lyon College, Oklahoma Panhandle State University, Southwestern Assemblies of God University, Texas College, Texas Wesleyan University and Wayland Baptist. Coach of the Year: Quinton Morgan – Langston University Offensive Player of the Year: C. J. Collins, Quarterback – Southwestern Assemblies of God University Defensive Player of the Year: Jamarae Finnie, Defensive Line – Langston University Special Teams Player of the Year: Derek Brush, Punter/Kicker – Arizona Christian University Newcomer of the Year: James Cox, Linebacker - Langston University Freshman of the Year: Dennis Gafford, Defensive Back – Langston University Athlete of the Year: Jaylen Lowe, Quarterback / Punter – Langston University FIRST-TEAM – OFFENSE Pos. Player Class School Hometown QB C. J. Collins Junior Southwestern Assemblies of God Bosqueville, Texas RB Titus Nelson Freshman Lyon College Zachary, Louisiana RB Orlando Haymon Junior Oklahoma Panhandle State Univ. Vernon, Texas RB J. P. Lowery Senior Southwestern Assemblies of God League City, Texas WR Grayland Dunams Senior Bacone College Henderson, Texas WR Cedrick Jackson Senior Langston University Marrero, Louisiana WR Jeremy Carr Junior Southwestern Assemblies of God Austin, Texas TE Jonathan Hendrix Senior Lyon College Batesville, Arkansas OL Christopher Carillo Junior Langston University Midland, Texas OL Tyler Vanlandingham Junior Lyon College Memphis, Tennessee OL Jakob Popple Senior Oklahoma Panhandle State Univ. -

Marion Greenwood in Tennessee (Exhibition Catalogue)

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Ewing Gallery of Art & Architecture Art 2014 Marion Greenwood in Tennessee (Exhibition Catalogue) Sam Yates The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Frederick Moffatt The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_ewing Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Painting Commons Recommended Citation Yates, Sam and Moffatt, Frederick, "Marion Greenwood in Tennessee (Exhibition Catalogue)" (2014). Ewing Gallery of Art & Architecture. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_ewing/1 This Publication is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ewing Gallery of Art & Architecture by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARION GREENWOOD in TENNESSEE MARION GREENWOOD in TENNESSEE This catalogue is produced on the occasion of Marion Greenwood in Tennessee at the UT Downtown Gallery, Knoxville, TN, June 6 - August 9, 2014. © Copyright of the Ewing Gallery of Art and Architecture, 2014. UT Downtown Gallery Director and Curator: Sam Yates Manager: Mike C. Berry Catalogue editor: Sam Yates foreword by: Sam Yates Catalogue design and copy editing: Sarah McFalls essay by: Dr. Frederick C. Moffatt Printed by UT Graphic Arts Services Photography credits: Detail images of The History of Tennessee (p. 2-6), image of The History of Tennessee (p. 1 and 10-11) installation photographs, preparatory sketches (p. 20) Haitian Nights (p 22) Haitian Work Song in the Jungle (p.