Inspirational Leadership Curriculum for Grades 8-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Founding Membership List

Founding Members of the Guardians of Culture Membership Group Institutions and Affiliated Organizations Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Alaska Native Language Archive Alcatraz Cruises Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. ASU American Indian Policy Institute Audrey and Harry Hawthorn Library and Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology Barona Cultural Center & Museum Caddo Heritage Museum Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Chickasaw Nation Cultural Center Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Dine College Dr. Fernando Escalante Community Library & Resource Center Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria George W. Brown Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center Hopi Tutuquyki Sikisve Huna Heritage Foundation International Buddhist Ethics Committee & Buddhist Tribunal on Human Rights Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma John G. Neihardt State Historic Site KCS Solutions, Inc. Maitreya Buddhist University Midwest Art Conservation Center Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Museo + Archivio, Inc. Museum Association of Arizona National Museum of the American Indian Newberry Library Noksi Press Osage Tribal Museum Papahana Kuaola Pawnee Nation College Pechanga Cultural Resources Department Poarch Creek Indians Quatrefoil Associates Chippewas of Rama First Nation Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute Speaking Place Tantaquidgeon Museum The Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University The Autry National Center of the American West The -

March 1St-18Th, 2012

www.oeta.tv KETA-TV 13 Oklahoma City KOED-TV 11 Tulsa KOET-TV 3 Eufaula KWET-TV 12 Cheyenne Volume 42 Number 9 A Publication of the Oklahoma Educational Television Authority Foundation, Inc. March 1ST-18 TH, 2012 MARCH 2012 THIS MONTH page page page page 2 4 5 6 Phantom of the Opera 60s Pop, Rock & Soul Dr. Wayne Dyer: Wishes Fulfilled Live from the Artists Den: Adele at Royal Albert Hall f March 6 & 14 @ 7 p.m. f March 5 @ 7 p.m. f March 30 @ 9w p.m. f March 7 @ 7 p.m. 2page FESTIVAL “The Phantom of the Opera” at the Royal Albert Hall f Wednesday March 7 at 7 p.m. Don’t miss a fully-staged, lavish 25th anniversary mounting of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s long-running Broadway and West End extravaganza. To mark the musical’s Silver Anniversary, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Cam- eron Mackintosh presented “The Phantom of the Opera” in the sumptuous Victorian splendor of London’s Royal Albert Hall. This dazzling restaging of the original production recreates the jaw-dropping scenery and breath- Under the Streetlamp taking special effects of the original, set to Lloyd Webber’s haunting score. f Tuesday March 13 at 7 p.m. The production stars Ramin Karimloo as The Phantom and Sierra Boggess Under the Streetlamp, America’s hottest new vocal group, as Christine, together with a cast and orchestra of more than 200, including performs an electrifying evening of classic hits from the special guest appearances by the original Phantom and Christine, Michael American radio songbook in this special recorded at the Crawford and Sarah Brightman. -

A Tribute to Betty Price Thank You, Betty

IMPROVING LIVES THROUGH THE ARTSNEWSLETTER OF THE OKLAHOMA ARTS COUNCIL FALL 2007 Thank You, Betty or 33 years, Betty Price has been the voice of the Oklahoma Arts Council. Recently retired Fas Executive Director, Price has been at the helm of this state agency for most of its existence. We couldn’t think of anyone more eloquent than her good friend, Judge Robert Henry to celebrate Betty and her passionate commitment to Oklahoma and to the arts. We join Judge Henry and countless friends in wishing Betty a long, happy and productive retirement. A Tribute to Betty Price From Judge Robert Henry ur great President John Fitzgerald Kennedy once noted: “To further the appreciation of Oculture among all the people, to increase respect for the creative individual, to widen participation by all the processes and fulfillments of art -- this is one of the fascinating challenges of these days.” Betty Price took that challenge more seriously than any other Oklahoman. And, it is almost impossible to imagine what Oklahoma’s cultural landscape would look like without her gentle, dignified, and incredibly Betty in front of the We Belong to the Land mural by Jeff Dodd. persistent vision. Photo by Keith Rinerson forMattison Avenue Publishing Interim Director. Finally, she was selected by the Council to serve as its Executive Director. Betty, it seems, has survived more Oklahoma governors than any institution except our capitol; she has done it with unparalleled integrity and artistic accomplishment. Betty and Judge Robert Henry during the dedication of the Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher portrait by Mitsuno Reedy. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

THE BASIC SOCIAL PROCESSES of WOMEN in the MILITARY Manda V. Hicks a Dissertation Submitted T

NEGOTIATING GENDERED EXPECTATIONS: THE BASIC SOCIAL PROCESSES OF WOMEN IN THE MILITARY Manda V. Hicks A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2011 Committee: Sandra Faulkner, Advisor Melissa K. Miller, Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Gorsevski Linda Dixon Vikki Krane ii ABSTRACT Sandra L. Faulkner, Advisor This research identifies the basic social processes for women in the military. Using grounded theory and feminist standpoint theories, I interviewed 38 active-duty and veteran service women. Feminist standpoint theories argue that within an institution, people who are the minority, oppressed, or disenfranchised will have a greater understanding of the institution than those who are privileged by it. Based on this understanding of feminist standpoint theories, this research argues that female service members will have a more expansive and diverse understanding of gender and military culture than male service members. I encouraged women to tell the story of their military experience and used analysis of narrative to identify the core categories of joining, learning, progressing, enduring, and ending. For women service members, the core variable of negotiating gendered expectations occurred throughout the basic social processes and primarily involved life choices, abilities, and sexual agency. This research serves as a forum for the lived experience of women in the military; through these articulations a set of particular standpoints regarding gender, war, and military culture emerge. Additionally, these data offer useful approaches to operating within male- dominated institutions and provide productive strategies for avoiding and challenging discrimination, harassment, and assault. -

Indian Education for All Connecting Cultures & Classrooms K-12 Curriculum Guide (Language Arts, Science, Social Studies)

Indian Education for All Connecting Cultures & Classrooms K-12 Curriculum Guide (Language Arts, Science, Social Studies) Montana Office of Public Instruction Linda McCulloch, Superintendent In-state toll free 1-888-231-9393 www.opi.mt.gov/IndianEd Connecting Cultures and Classrooms INDIAN EDUCATION FOR ALL K-12 Curriculum Guide Language Arts, Science, Social Studies Developed by Sandra J. Fox, Ed. D. National Indian School Board Association Polson, Montana and OPI Spring 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................... i Guidelines for Integrating American Indian Content ................. ii Using This Curriculum Guide ....................................................... 1 Section I Language Arts ...................................................................... 3 Language Arts Resources/Activities K-4 ............................ 8 Language Arts Resources/Activities 5-8 ............................. 16 Language Arts Resources/Activities 9-12 ........................... 20 Section II Science .................................................................................... 28 Science Resources/Activities K-4 ......................................... 36 Science Resources/Activities 5-8 .......................................... 42 Science Resources/Activities 9-12 ........................................ 50 Section III Social Studies ......................................................................... 58 Social Studies Resources/Activities K-4 ............................. -

Maria Tall Chief Maria Tall Chief

Maria Tall Chief Maria Tall Chief (later changed to Tallchief) was born in Oklahoma in 1925. Her father was Osage Native American and her mother of Scotch-Irish descent. It had been an unrealized dream of her mom to study dance and music, so Maria and her sister Marjorie were enrolled early in dance and piano lessons. Maria was only three years old when she began dance classes. It wasn’t long before Maria and Marjorie were performing at local rodeos. When she was eight, Maria’s family moved to California with the hope finding an opportunity for the girls in show business. Her mother asked a pharmacist for a recommendation for a dance teacher and was referred to Ernest Belcher, who was Marge Champion’s father. Maria soon moved on to more noted classical teachers of dance, but was also continuing to study piano and saw herself as having a career as a classical pianist. However, she continued with dance and at 17 went to New York looking for a way into the classical world of dance. Tallchief was soon offered a place with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo where she performed for five years. It was there that she met George Balanchine. She eventually married Balanchine and returned to New York. Balanchine had just founded the New York City Ballet and Maria became its first prima ballerina. She was the first American woman and the first Native American to be recognized world wide as a prima ballerina. She was the first American invited to dance with the Bolshoi. -

The Frontier, November 1932

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 University of Montana Publications 11-1932 The Frontier, November 1932 Harold G. Merriam Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Merriam, Harold G., "The Frontier, November 1932" (1932). The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939. 41. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier/41 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V'«l o P i THE1$III! NOVEMBER, 1932 FRONTIER A MAGAZINt Of THf NORTHWfST THE WEST—A LOST CHAPTER c a r e y McW il l ia m s THE SIXES RUNS TO THE SEA Story by HOWARD McKINLEY CORNING SCOUTING WITH THE U. S. ARMY, 1876-77 J. W. REDINGTON THE RESERVATION JOHN M. KLINE Poems by Jason Bolles, Mary B. Clapp, A . E. Clements, Ethel R. Fuller, G. Frank Goodpasture, Raymond Kresensky, Queene B. Lister, Lydia Littell, Catherine Macleod, Charles Olsen, Lawrence Pratt, Lucy Robinson, Claite A . Thom son, Harold Vinal, Elizabeth Waters, W . A. Ward, Gale Wilhelm, Anne Zuker. O T H E R STO R IE S by Brassil Fitzgerald and Harry Huse. -

= Roster - ~ : of Members

:1111111111111 "1"'111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111E § i = = ~ ~ = ROSTER - ~ : OF MEMBERS - OF THE 353RD - - INFANTRY i - - - - - - - = - - -ill lit IIIIIUUIIIIIIIIIIIIIIU UWtMtltolllllllll U UIUU I U 11111111 U I uro- iiiiiiiimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii', THE 353RD INFANTRY | REGIMENTAL SOCIETY I SEPTEMBER. 1917 | JUNE. 1919 I IllltllUtll ................................................................................................. ..... ROSTER m u ......... ACCORDING TO THE PLACE ............... OF RESIDENCE iiiiiiiiiiii ......................................................... PREPARED FOR D 1 S T R IB U T 1 0 N TO ..... MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY AT THE REGIMENTAL REUNION. SEPTEMBER. 1922 ................................ n 1111111111111 • 111111111<111111111111111111111•111111111•11111111ii11111111 it iiiiiiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiHimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiumiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiintiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiifiiiiiiiiiiiiMiMiiiiiiiiMiiic1111111111«11111111111111 ■ 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 llj; PREFACE This little booklet contains the names and addresses of all former members of the Regiment whose names and addresses were known at the time the book was com piled. There are bound to be er rors. Men move from place to place and very seldom think of notifying the Secretary of change of address. This book is Intended to encour age visiting among former mem bers of the Regiment. It is too bad it cannot be absolutely cor rect for the will to visit a former -

Good Morning Everyone and Welcome to the Massachusetts State Track Coaches

Good morning everyone and welcome to the Massachusetts State Track Coaches Association’s induction ceremony of former cross country and track and field greats from Massachusetts. These athletes, when competing in high school, in college or beyond, established themselves amongst the best that this state, this country and even this world has ever seen. My name is Bob L’Homme and I coach both the Cross Country and Track and Field teams at Bishop Feehan High School in Attleboro, Ma. And on behalf of the Hall of Fame Committee, Chuck Martin, Jayson Sylvain, Tim Cimeno and Mike Glennon I’d like to thank you all for attending. I am the chairman of the Hall of Fame Committee and I will be your MC for this morning’s induction ceremony. The state of Massachusetts currently has approximately 100 athletes that have been inducted into the Hall of Fame. Names like Johnny Kelley, Billy Squires, John Thomas, Alberto Salazar, Lynn Jennings, Mark Coogan, Calvin Davis, and Shalane Flanagan to name a few are sprinkled within those 100 athletes. Last year we inducted Abby D’Agostino from Masconomet High School, Fred Lewis from Springfield Tech, Karim Ben Saunders from Cambridge R&L, Anne Jennings of Falmouth, Arantxa King of Medford, Ron Wayne of Brockton and Heather Oldham of Woburn H.S. All of these past inductees were your high school league champions, divisional champions, state champions, New England champions, Division 1, 2 and 3 collegiate champions and High School and collegiate All Americans. There are United States Champions, Pan Am Champions, World Champions and Olympic Champions. -

1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

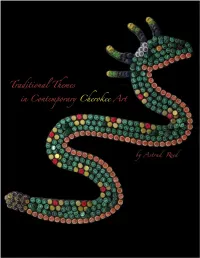

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword "What About Indian Art?" An Interview with Dr. Mary Jo Watson Director, School of Art and Art History / Regents Professor of Art History KGOU Radio Interview by Brant Morrell • April 17, 2013 Twenty years ago, a degree in Native American Art and Art History was non-existent. Even today, only a few universities offer Native Art programs, but at the University of Oklahoma Mary Jo Watson is responsible for launching a groundbreaking art program with an emphasis on the indigenous perspective. You expect a director of an art program at a major university to have pieces in their office, but entering Watson’s workspace feels like stepping into a Native art museum. -

Setting a New Course in Native American Protest Movements: the Menominee Warrior Society’S Takeover of the Alexian Brothers Novitiate in 1975

Setting a New Course in Native American Protest Movements: The Menominee Warrior Society’s Takeover of the Alexian Brothers Novitiate in 1975 Rachel Lavender Capstone Advisor: Dr. Patricia Turner Cooperating Professors: Dr. Andrew Sturtevant and Dr. Heather Ann Moody History 489 December, 2017 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Table of Contents Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 1 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 2 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 4 Secondary Literature……………………………………………………………………. Pg. 7 Long Term Causes: Menominee Termination and D.R.U.M.S…………..…………….. Pg. 14 Trigger………………………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 20 The Takeover: A Collision of Tactics Ada Deer and Legislative Change……………………………………………… Pg. 22 The Menominee Warrior Society and Direct Action…………………………… Pg. 27 After Gresham: Conclusion…………………………………………………………….. Pg. 30 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 35 1 Abstract Abstract: In the 1960s and 1970s, the United States experienced multiple Native American protest movements. These movements came from two different methods of protest: direct action, or grassroots tactics, and long-term political strategies.. The first method, grassroots tactics, was exemplified by groups such as the American Indian Movement and the Menominee Warrior Society. The occupations of Alcatraz Wounded Knee and the BIA, as well as the takeover of the Alexian Brothers Novitiate all represented the use of grassroots tactics. The second method of protest was that of peaceful change through legislation, or political strategies. The D.R.U.M.S. movement, the Menominee Restoration Committee and the political activism of Ada Deer all represented the use of political strategies.