Bacone College's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS 7536 Pochoir Prints of Ledger Drawings by the Kiowa Five

MS 7536 Pochoir prints of ledger drawings by the Kiowa Five National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Local Numbers................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical................................................................................................... -

Founding Membership List

Founding Members of the Guardians of Culture Membership Group Institutions and Affiliated Organizations Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Alaska Native Language Archive Alcatraz Cruises Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. ASU American Indian Policy Institute Audrey and Harry Hawthorn Library and Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology Barona Cultural Center & Museum Caddo Heritage Museum Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Chickasaw Nation Cultural Center Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Dine College Dr. Fernando Escalante Community Library & Resource Center Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria George W. Brown Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center Hopi Tutuquyki Sikisve Huna Heritage Foundation International Buddhist Ethics Committee & Buddhist Tribunal on Human Rights Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma John G. Neihardt State Historic Site KCS Solutions, Inc. Maitreya Buddhist University Midwest Art Conservation Center Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Museo + Archivio, Inc. Museum Association of Arizona National Museum of the American Indian Newberry Library Noksi Press Osage Tribal Museum Papahana Kuaola Pawnee Nation College Pechanga Cultural Resources Department Poarch Creek Indians Quatrefoil Associates Chippewas of Rama First Nation Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute Speaking Place Tantaquidgeon Museum The Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University The Autry National Center of the American West The -

Artist Ruthe Blalock Jones to Join Circle of Honor | the Journal Record

Artist Ruthe Blalock Jones to join Circle of Honor | The Journal Record Log out Manage Account Subscribe HOME NEWS EVENTS COMMUNITY MARKETPLACE NEW MEDIA ADVERTISE USAGE FAQ LEGISLATIVE REPORT PUBLIC NOTICE CLASSIFIEDS THE JOURNAL RECORD > ALL-MOBILE-NEWS > ARTIST RUTHE BLALOCK JONES TO JOIN CIRCLE OF HONOR Artist Ruthe Blalock Jones to join Circle of Honor By David Page The Journal Record Special Projects Editor Posted: 02:23 PM Monday, November 18, 2013 Like Tweet 2 0 0 TULSA – At age 13, Ruthe Blalock Jones entered the annual Philbrook Indian art show in Tulsa. Jones said the artist Charles Banks Wilson and his wife encouraged her to enter the art show. Wilson, who died this year, has portraits of Woody Guthrie, Will Rogers and Jim Thorpe on display at the state Capitol in Oklahoma City. Jones earned an honorable mention. “It did not dawn on me until later that it was an adult competition.” 138,460,823 131,886,428 From that early success, Jones went on to have a long career as a professional artist and educator. Her art 101,840,413 has been exhibited internationally, including recent 424,326,663 showings in Japan and Uganda. She spent 30 years at Bacone College in Muskogee as a professor of art and director of art. (Ruthe Blalock Jones) Jones, of Shawnee-Delaware-Peoria descent, will be Business Calendar honored for her accomplishments and long career Today Tuesday, November 19 P when the Tulsa City-County Library’s American Resource Center inducts her into the Circle of Honor. The induction ceremony is scheduled at 10:30 a.m. -

1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

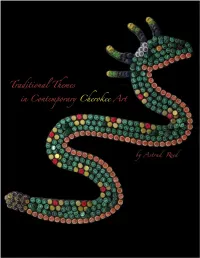

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword "What About Indian Art?" An Interview with Dr. Mary Jo Watson Director, School of Art and Art History / Regents Professor of Art History KGOU Radio Interview by Brant Morrell • April 17, 2013 Twenty years ago, a degree in Native American Art and Art History was non-existent. Even today, only a few universities offer Native Art programs, but at the University of Oklahoma Mary Jo Watson is responsible for launching a groundbreaking art program with an emphasis on the indigenous perspective. You expect a director of an art program at a major university to have pieces in their office, but entering Watson’s workspace feels like stepping into a Native art museum. -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

Painting Culture, Painting Nature Stephen Mopope, Oscar Jacobson, and the Development of Indian Art in Oklahoma by Gunlög Fur

UNIVERSITY OF FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OKLAHOMA PRESS 9780806162874.TIF BOOKNEWS Explores indigenous and immigrant experiences in the development of American Indian art Painting Culture, Painting Nature Stephen Mopope, Oscar Jacobson, and the Development of Indian Art in Oklahoma By Gunlög Fur In the late 1920s, a group of young Kiowa artists, pursuing their education at the University of Oklahoma, encountered Swedish-born art professor Oscar Brousse Jacobson (1882–1966). With Jacobson’s instruction and friendship, the Kiowa Six, as they are now known, ignited a spectacular movement in American Indian art. Jacobson, who was himself an accomplished painter, shared a lifelong bond with group member Stephen Mopope (1898–1974), a prolific Kiowa painter, dancer, and musician. Painting Culture, Painting Nature explores the joint creativity of these two visionary figures and reveals how indigenous and immigrant communities of the MAY 2019 early twentieth century traversed cultural, social, and racial divides. $34.95s CLOTH 978-0-8061-6287-4 368 PAGES, 6 X 9 Painting Culture, Painting Nature is a story of concurrences. For a specific period 15 COLOR AND 22 B&W ILLUS., 3 MAPS immigrants such as Jacobson and disenfranchised indigenous people such as ART/AMERICAN INDIAN Mopope transformed Oklahoma into the center of exciting new developments in Indian art, which quickly spread to other parts of the United States and to Europe. FOR AUTHOR INTERVIEWS AND OTHER Jacobson and Mopope came from radically different worlds, and were on unequal PUBLICITY INQUIRIES CONTACT: footing in terms of power and equality, but they both experienced, according to KATIE BAKER, PUBLICITY MANAGER author Gunlög Fur, forms of diaspora or displacement. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991

BILLIE JANE BAGULEY LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES HEARD MUSEUM 2301 N. Central Avenue ▪ Phoenix AZ 85004 ▪ 602-252-8840 www.heard.org Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991 RC 10 Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century 2 Call Number: RC 10 Extent: Approximately 3 linear feet; copy photography, exhibition and publication records. Processed by: Richard Pearce-Moses, 1994-1995; revised by LaRee Bates, 2002. Revised, descriptions added and summary of contents added by Craig Swick, November 2009. Revised, descriptions added by Dwight Lanmon, November 2018. Provenance: Collection was assembled by the curatorial department of the Heard Museum. Arrangement: Arrangement imposed by archivist and curators. Copyright and Permissions: Copyright to the works of art is held by the artist, their heirs, assignees, or legatees. Copyright to the copy photography and records created by Heard Museum staff is held by the Heard Museum. Requests to reproduce, publish, or exhibit a photograph of an art works requires permissions of the artist and the museum. In all cases, the patron agrees to hold the Heard Museum harmless and indemnify the museum for any and all claims arising from use of the reproductions. Restrictions: Patrons must obtain written permission to reproduce or publish photographs of the Heard Museum’s holdings. Images must be reproduced in their entirety; they may not be cropped, overprinted, printed on colored stock, or bleed off the page. The Heard Museum reserves the right to examine proofs and captions for accuracy and sensitivity prior to publication with the right to revise, if necessary. -

The Szwedzicki Portfolios: Native American Fine Art and American Visual Culture 1917-1952

1 The Szwedzicki Portfolios: Native American Fine Art and American Visual Culture 1917-1952 Janet Catherine Berlo October 2008 2 Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Native American Painting as Modern Art The Publisher: l’Edition d’Art C. Szwedzicki . 25 Kiowa Indian Art, 1929 . .27 The Author The Subject Matter and the Artists The Pochoir Technique Pueblo Indian Painting, 1932 . 40 The Author The Subject Matter and the Artists Pueblo Indian Pottery, 1933-36 . 50 The Author The Subject Matter Sioux Indian Painting, 1938 . .59 The Subject Matter and the Artists American Indian Painters, 1950 . 66 The Subject Matter and the Artists North American Indian Costumes, 1952 . 81 The Artist: Oscar Howe The Subject Matter Collaboration, Patronage, Mentorship and Entrepreneurship . 90 Conclusion: Native American Art after 1952 . 99 Acknowledgements . 104 About the Author . 104 3 Introduction In 1929, a small French art press previously unknown to audiences in the United States published a portfolio of thirty plates entitled Kiowa Indian Art. This was the most elegant and meticulous publication on American Indian art ever offered for sale. Its publication came at a time when American Indian art of the West and Southwest was prominent in the public imagination. Of particular interest to the art world in that decade were the new watercolors being made by Kiowa and Pueblo artists; a place was being made for their display within the realm of the American “fine arts” traditions in museums and art galleries all over the country. Kiowa Indian Art and the five successive portfolios published by l’Edition d’Art C. -

The Clemente Course in the Humanities;' National Endowment for the Humanities, 2014, Web

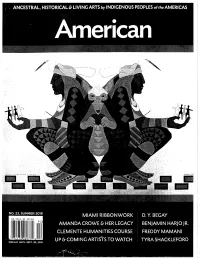

F1rstAmericanArt ISSUE NO. 23, SUMMER 2019 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Take a Closer Look: 24 Recent Developments 16 Four Emerging Artists By Mariah L. Ashbacher Shine in the Spotlight and America Meredith By RoseMary Diaz ( Cherokee Nation) (Santa Clara Tewa) Seven Directions 20 Amanda Crowe & Her Legacy: 30 By Hallie Winter (Osage Nation) Eastern Band Cherokee Art+ Literature 96 Woodcarving Suzan Shown Harjo By Tammi). Hanawalt, PhD By Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD peepankisaapiikahkia 36 Collections: 100 eehkwaatamenki aacimooni: The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Story of Miami Ribbonwork By Andrea L. Ferber, PhD By Scott M. Shoemaker, PhD Spotlight: Melt: Prayers 104 (Miami), George Ironstrack for the People and the Planet, (Miami), and Karen Baldwin Angela Babby (Oglala Lakota) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Reclaiming Space in Native 44 Calendar 109 Knowledges and Languages By Travis D. Day and America The Clemente Course Meredith (Cherokee Nation) in the Humanities By Laura Marshall Clark (Muscogee Creek) REVIEWS Exhibition Reviews 78 ARTIST PROFILES Book Review 94 D. Y.Begay: 54 Dine Textile Artist By Jennifer McLerran, PhD IN MEMORIAM Benjamin Harjo Jr.: 60 Joe Fafard, OC, SOM (Melis) 106 Absentee Shawnee/Seminole Painter By Gloria Bell, PhD (Metis) and Printmaker Frank LaPefta 107 By Staci Golar (Nomtipom Maidu) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Freddy Mamani Silvestre: 66 Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk) Aymara Architect By jean Merz-Edwards By Vivian Zavataro, PhD Tyra Shackleford: 72 Chickasaw Textile Artist By Vicki Monks (Chickasaw) COVER Benjamin Harjo 'Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/ Seminole), creator and coyote compete to make man, 2016, gouache on Arches watercolor paper, 20 x 28 in., private collection. -

B Y S U S a N D R a G

NATIVE AMERICANS AND WESTERN ICONS HAVE BEEN THE TWIN PILLARS OF OKLAHOMA’S CULTURE SINCE WELL BEFORE STATEHOOD. WE ASSEMBLED TWO PANELS OF EXPERTS TO DETERMINE WHICH BRAVE, HARDWORKING, JUSTICE-SEEKING, FRONTIER-TAMING INDIVIDUALS DESERVE A PLACE IN OKLAHOMA’S WESTERN PANTHEON. THE RESULT IS THE FOLLOWING LIST OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL NATIVE AMERICANS, COWBOYS, AND COWGIRLS IN THE STATE’S HISTORY. BY SUSAN DRAGOO OklahomaToday.com 41 BILL ANOATUBBY BEUTLER FAMILY (b. 1945) Their stock was considered a CHICKASAW NATION CHICKASAW Bill Anoatubby grew up in Tisho- cowboy’s nightmare, but that mingo and first went to work was high praise for the Elk City- for the Chickasaw Nation as its RANDY BEUTLER COLLECTION based Beutler Brothers—Elra health services director in 1975. (1896-1987), Jake (1903-1975), He was elected governor of the and Lynn (1905-1999)—who Chickasaws in 1987 and now is in 1929 founded a livestock in his eighth term and twenty-ninth year in that office. He has contracting company that became one of the world’s largest worked to strengthen the nation’s foundation by diversifying rodeo producers. The Beutlers had an eye for bad bulls and its economy, leading the tribe into the twenty-first century as a tough broncs; one of their most famous animals, a bull politically and economically stable entity. The nation’s success named Speck, was successfully ridden only five times in more has brought prosperity: Every Chickasaw can access education than a hundred tries. The Beutler legacy lives on in a Roger benefits, scholarships, and health care. -

Art for All the Swedish Experience in Mid-America Art for All the Swedish Experience in Mid-America

Art for All The Swedish Experience in Mid-America Art for All The Swedish Experience in Mid-America by Cori Sherman North, Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery Curator with an essay contributed by Donald Myers, Director of the Hillstrom Museum of Art at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, and introduction and acknowledgements by Ron Michael, Sandzén Gallery Director August 25 through October 20, 2019 2021: Dates to be Determined 2021/22: Dates to be Determined Hillstrom Museum of Art Introduction and Acknowledgements The inclination for the Birger Sandzén Memorial appreciate Director Karin Abercrombie’s assistance to Gallery to develop an ambitious, though certainly not make it happen. comprehensive, exhibition of early Swedish-American artwork has been brewing since the Gallery’s Conservation of several paintings from the Sandzén inception in 1957. Jonas Olof Grafström was one of Gallery’s permanent collection was made possible the true pioneers in this field and his history helped by a generous grant from the Swedish Council of spark the idea for this show. Additionally, there have America, a national non-profit organization dedicated been many instances of these artists making their to preserving and promoting Swedish heritage. way into exhibitions here, but none as far-reaching They also provided support for the printing of this as Art for All. Our namesake, Birger Sandzén, had catalogue. We are deeply grateful to them and hope ties to nearly all of the painters, printmakers, and the organization’s members will be proud of the sculptors represented, showing his amazing ability to exhibition. network. Therefore, it’s fitting that we finally tackle this incredible association of artists and their work, which We are also grateful to those who loaned works from was so important in building an appreciation for art in their collections to help add depth.