1Ce1o039p 959426.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

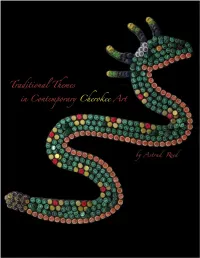

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword "What About Indian Art?" An Interview with Dr. Mary Jo Watson Director, School of Art and Art History / Regents Professor of Art History KGOU Radio Interview by Brant Morrell • April 17, 2013 Twenty years ago, a degree in Native American Art and Art History was non-existent. Even today, only a few universities offer Native Art programs, but at the University of Oklahoma Mary Jo Watson is responsible for launching a groundbreaking art program with an emphasis on the indigenous perspective. You expect a director of an art program at a major university to have pieces in their office, but entering Watson’s workspace feels like stepping into a Native art museum. -

Cherokee Pottery

Ewf gcQl q<HhJJ Cherokee Pottery a/xW n A~ aGw People of One Fire D u n c a n R i g g s R o d n i n g Y a n t z ISBN: 0-9742818-2-4 Text by:Barbara Duncan, Brett H. Riggs, Christopher B. Rodning and I. Mickel Yantz, Design and Photography, unless noted: I. Mickel Yantz Copyright © 2007 Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc PO Box 515, Tahlequah, Oklahoma 74465 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage system or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Cover: Arkansas Applique’ by Jane Osti, 2005. Cherokee Heritage Center Back Cover: Wa da du ga, Dragonfly by Victoria McKinney, 2007; Courtesy of artist. Right: Fire Pot by Nancy Enkey, 2006; Courtesy of artist. Ewf gcQl q<HhJJ Cherokee Pottery a/xW n A~ aGw People of One Fire Dr. Barbara Duncan, Dr. Brett H. Riggs, Christopher B. Rodning, and I. Mickel Yantz Cherokee Heritage Center Tahlequah, Oklahoma Published by Cherokee Heritage Press 2007 3 Stamped Pot, c. 900-1500AD; Cherokee Heritage Center 2, Cherokee people who have been living in the southeastern portion of North America have had a working relationship with the earth for more than 3000 years. They took clay deposits from the Smokey Mountains and surrounding areas and taught themselves how to shape, decorate, mold and fire this material to be used for utilitarian, ceremonial and decorative uses. -

The Lost Arts Project - 1988

The Lost Arts Project - 1988 The Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. and the Cherokee Nation partnered in 1988 to create the Lost Arts Program focusing on the preservation and revival of cultural arts. A new designation was created for Master Craftsmen who not only mastered their art, but passed their knowledge on to the next generation. Stated in the original 1988 brochure: “The Cherokee people are at a very important time in history and at a crucial point in making provisions for their future identity as a distinct people. The Lost Arts project is concerned with the preservation and revival of Cherokee cultural practices that any be lost in the passage from one generation to another. The project is concerned with capturing the knowledge, techniques, individual commitment available to us and heritage received from Cherokee folk artists and developing educational and cultural preservation programs based on their knowledge and experience.” Artists had to be Cherokee and nominated by at least two people in the community. When selected, they were designated as “Living National Treasures.” 24 1 Do you know these Treasures? Lyman Vann - 1988 Bow Making Mattie Drum - 1990 Weaving Rogers McLemore - 1990 Weaving Hester Guess - 1990 Weaving Sally Lacy - 1990 Weaving Stella Livers - 1990 Basketry Eva Smith - 1991 Turtle Shell Shackles Betty Garner - 1993 Basketry Vivian Leaf Bush -1993 Turtle Shell Shackles David Neugin - 1994 Bow Making Vivian Elaine Waytula - 1995 Basketry Richard Rowe 1996 Carving Lee Foreman - 1999 Marble Making Original Lost Arts Program Exhibit Flyer- 1988 Mildred Justice Ketcher - 1999 Basketry Albert Wofford - 1999 Gig Making/Carving Willie Jumper - 2001 Stickball Sticks Sam Lee Still - 2002 Carving Linda Mouse-Hansen - 2002 Basketry Unfortunately, we have not been able to locate information, pictures or examples of art from the following Treasures. -

Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE)

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: Cherokee (ch Eh – ruh – k EE) Nation Tribal website(s): http//www.cherokee.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” • The Cherokees are original residents of the American southeast region, particularly Georgia, North and South Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Most Cherokees were forced to move to Oklahoma in the 1800's along the Trail of Tears. Descendants of the Cherokee Indians who survived this death march still live in Oklahoma today. Some Cherokees escaped the Trail of Tears by hiding in the Appalachian hills or taking shelter with sympathetic white neighbors. The descendants of these people live scattered throughout the original Cherokee Indian homelands. After the Civil War more a new treaty allowed the government to dispose of land in the Cherokee Outlet. The settlement of several tribes in the eastern part of the Cherokee Outlet (including the Kaw, Osage, Pawnee, Ponca, and Tonkawa tribes) separated it from the Cherokee Nation proper and left them unable to use it for grazing or hunting. -

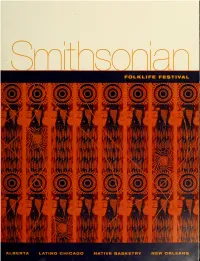

NATIVE BASKETRY NEW ORLEANS W'ms

ALBERTA LATINO CHICAGO NATIVE BASKETRY NEW ORLEANS W'ms. 40th Annual Smithsonian Foli<life Festival Alberta AT THE SMITHSONIAN Carriers of Culture LIVING NATIVE BASKET TRADITIONS Nuestra Musica LATINO CHICAGO Been in the Storm So Lon SPECIAL EVENING CONCERT SERIES Washington, D.C. june 3o-july n, 2006 The annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival brings together exemplary practitioners of diverse traditions, both old and new, from communities across the United States and around the world. The goal of the traditions Festival is to strengthen and preserve these by presenting them on the National Mall, so that with the tradition-bearers and the public can connect and learn from one another, and understand cultural differences in a respectful way. Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 750 9th Street NW, Suite 4100 Washington, D.C. 20560-0953 www.folklife.si.edu © 2006 Smithsonian Institution ISSN 1056-6805 Editor: Frank Proschan Art Director: Krystyn MacGregor Confair Production Manager: Joan Erdesky Graphic Designer: Zaki Ghul Design Interns: Annemarie Schoen and Sara Tierce-Hazard Printing: Stephenson Printing Inc., Alexandria, Virginia Smithsonian Folklife Festival The Festival is supported by federally appropriated funds; Smithsonian trust fijnds; contributions from governments, businesses, foundations, and individuals; in-kind assistance; and food, recording, and craft sales. General support for this year's programs includes the Music Performance Fund, with in-kind support for the Festival provided through Motorola, Nextel, WAMU-88.5 FM, WashingtonPost.com. Whole Foods Market. Pegasus Radio Corp., Icom America, and the Folklore Society of Greater Washington. The Festival is co-sponsored by the National Park Service. -

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers (Oklahoma Academic State Standards for Social Studies, OSDE)

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers (Oklahoma Academic State Standards for Social Studies, OSDE) Tribe:_______Cherokee (ch Eh – ruh – k EE) Nation________________ Tribal website(s): http//www.cherokee.org _________ 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and2the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” • The Cherokees are original residents of the American southeast region, particularly Georgia, North and South Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Most Cherokees were forced to move to Oklahoma in the 1800's along the Trail of Tears. Descendants of the Cherokee Indians who survived this death march still live in Oklahoma today. Some Cherokees escaped the Trail of Tears by hiding in the Appalachian hills or taking shelter with sympathetic white neighbors. The descendants of these people live scattered throughout the original Cherokee Indian homelands. After the Civil War more a new treaty allowed the government to dispose of land in the Cherokee Outlet. The settlement of several tribes in the eastern part of the Cherokee Outlet (including the Kaw, Osage, Pawnee, Ponca, and Tonkawa tribes) separated it from the Cherokee Nation proper and left them unable to use it for grazing or hunting. -

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers (Common Core State Standards for Social Studies, OSDE) Tribe:____Cherokee____ (ch EH - r uh - k EE) Tribal websites(s) http// www.cherokee.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” • The Cherokees are original residents of the American southeast region, particularly Georgia, North and South Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Most Cherokees were forced to move to Oklahoma in the 1800's along the Trail of Tears. Descendants of the Cherokee Indians who survived this death march still live in Oklahoma today. Some Cherokees escaped the Trail of Tears by hiding in the Appalachian hills or taking shelter with sympathetic white neighbors. The descendants of these people live scattered throughout the original Cherokee Indian homelands. After the Civil War more a new treaty allowed the government to dispose of land in the Cherokee Outlet. The settlement of several tribes in the eastern part of the Cherokee Outlet (including the Kaw, Osage, Pawnee, Ponca, and Tonkawa tribes) separated it from the Cherokee Nation proper and left them unable to use it for grazing or hunting. -

Isbn: 0-9742818-3-2

ISBN: 0-9742818-3-2 Text by Barbara R. Duncan Ph.D., Susan C. Powers Ph.D., and Martha Berry Design and layout by I. Mickel Yantz Copyright © 2008 Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc, PO Box 515, Tahlequah, OK 74465 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage system or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Cherokee Belt, c. 1860. Multi-colored glass seed beads; metallic beads; black wool cloth; red silk ribbon; cotton cloth; thread sewn. Photo Courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. John and Marva Warnock Beadwork Storytellers, a Visual Language Barbara R. Duncan Ph.D., Susan C. Powers Ph.D. and Martha Berry “Our Fires Still Burn,” beaded bandolier bag by Martha Berry, completed 2002. Photo by Dave Berry Published by Cherokee Heritage Press, 2008 Cherokee Beadwork by Barbara R. Duncan, Ph.D. Cherokee people have created designs with beads and other materials for millennia. Beads, adela, have been part of an array of adornment that has included gorgets of stone and shell; featherwork; the bones of animals, birds, snakes, fish, and shells of turtles; mica; woven materials; semi-precious gems; painted leather; quillwork; tattoos; and more. Materials were obtained from the southern Appalachians, the original homeland of the Cherokees, and from trade. As long as ten thousand years ago, trade networks extended to the Great Lakes, the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic coast, and the Mississippi River. -

100% Final Design | Content Set | May 17, 2018 Cherokee National Capitol Museum

100% FINAL DESIGN | CONTENT SET | MAY 17, 2018 CHEROKEE NATIONAL CAPITOL MUSEUM CONTENTS Exhibition Content Matrix 3 Artifact List 17 Graphic List 36 AV & Interactivity 79 100% Final Design | May 17, 2018 | Prepared by Ralph Appelbaum Associates CHEROKEE NATIONAL CAPITOL MUSEUM EXHIBITION CONTENT MATRIX 100% Final Design | May 17, 2018 | Prepared by Ralph Appelbaum Associates 3 CHEROKEE NATIONAL CAPITOL MUSEUM EXHIBITION CONTENT MATRIX May 17, 2018 SCHEMATIC DESIGN: Prepared by Ralph Appelbaum Associates NOTES: This document is a work in progress, and serves an overview of exhibit elements and associated content. Grey text indicates object items that may not fit in the current layout (locations to be confirmed). CODE ELEMENT THEME ZONE DESCRIPTION ARTIFACTS IMAGES MEDIA NOTES CODE 1-1 WELCOME AREA/ Designed to reflect Cherokee art and cultural LOBBY craft traditions 1-1_gs01 Secondary Copy: History of the • Capitol Building late 1800s. Cherokee National Capitol Image from OHS. 2393; RAA Building g#0001 1-1_gm01 Graphic Mural • Bird’s eye view of Tahlequah early 1900s. Image from OHS. 19409.2; RAA g#0002 RETAIL AREA Base-building FIT OUT scope: 1-2 • M.1.1 - Desk designed to house a POS system with building entrances in line of sight • M2.1-2.1; M3.1-3.2; M4.1-4.2 - Retail millwork • M.5.1 – Brochure rack 1-2_M.1.1 1-2_M.2.1- 2 1-2_M.3.1- 2 1-2_M.4.1- 2 1-2_M.5.1 1-4 CHANGING • Flexible space for temporary Base-building FIT OUT scope: GALLERY exhibits and art displays • Ceiling mounted projector and • Possibly used as a lecture roll-down screen for use as needed space in presentations or exhibits 1-4_gp01 Changing Gallery Introductory Copy 1-4_W.1.1- Base-building FIT OUT scope: 8 • Movable wall system 1-4_C.1.2-4 Artifacts will change with exhibits 1-5 TIMELESS CONTINUITY AREA 1-5_gs01 Secondary Copy: The Cherokee A primary written to connect the Origins story People to the Cherokee Nation today (placing emphasis on continuum).