Isbn: 0-9742818-3-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Great Pottery Projects

ceramic artsdaily.org 7 great pottery projects | Second Edition | tips on making complex pottery forms using basic throwing and handbuilding skills This special report is brought to you with the support of Atlantic Pottery Supply Inc. 7 Great Pottery Projects Tips on Making Complex Pottery Forms Using Basic Throwing and Handbuilding Skills There’s nothing more fun than putting your hands in clay, but when you get into the studio do you know what you want to make? With clay, there are so many projects to do, it’s hard to focus on which ones to do first. So, for those who may wany some step-by-step direction, here are 7 great pottery projects you can take on. The projects selected here are easy even though some may look complicated. But with our easy-to-follow format, you’ll be able to duplicate what some of these talented potters have described. These projects can be made with almost any type of ceramic clay and fired at the recommended temperature for that clay. You can also decorate the surfaces of these projects in any style you choose—just be sure to use food-safe glazes for any pots that will be used for food. Need some variation? Just combine different ideas with those of your own and create all- new projects. With the pottery techniques in this book, there are enough possibilities to last a lifetime! The Stilted Bucket Covered Jar Set by Jake Allee by Steve Davis-Rosenbaum As a college ceramics instructor, Jake enjoys a good The next time you make jars, why not make two and time just like anybody else and it shows with this bucket connect them. -

Cherokee Ethnogenesis in Southwestern North Carolina

The following chapter is from: The Archaeology of North Carolina: Three Archaeological Symposia Charles R. Ewen – Co-Editor Thomas R. Whyte – Co-Editor R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. – Co-Editor North Carolina Archaeological Council Publication Number 30 2011 Available online at: http://www.rla.unc.edu/NCAC/Publications/NCAC30/index.html CHEROKEE ETHNOGENESIS IN SOUTHWESTERN NORTH CAROLINA Christopher B. Rodning Dozens of Cherokee towns dotted the river valleys of the Appalachian Summit province in southwestern North Carolina during the eighteenth century (Figure 16-1; Dickens 1967, 1978, 1979; Perdue 1998; Persico 1979; Shumate et al. 2005; Smith 1979). What developments led to the formation of these Cherokee towns? Of course, native people had been living in the Appalachian Summit for thousands of years, through the Paleoindian, Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippi periods (Dickens 1976; Keel 1976; Purrington 1983; Ward and Davis 1999). What are the archaeological correlates of Cherokee culture, when are they visible archaeologically, and what can archaeology contribute to knowledge of the origins and development of Cherokee culture in southwestern North Carolina? Archaeologists, myself included, have often focused on the characteristics of pottery and other artifacts as clues about the development of Cherokee culture, which is a valid approach, but not the only approach (Dickens 1978, 1979, 1986; Hally 1986; Riggs and Rodning 2002; Rodning 2008; Schroedl 1986a; Wilson and Rodning 2002). In this paper (see also Rodning 2009a, 2010a, 2011b), I focus on the development of Cherokee towns and townhouses. Given the significance of towns and town affiliations to Cherokee identity and landscape during the 1700s (Boulware 2011; Chambers 2010; Smith 1979), I suggest that tracing the development of towns and townhouses helps us understand Cherokee ethnogenesis, more generally. -

Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory

DANGEROUSLY FREE: OUTLAWS AND NATION-MAKING IN LITERATURE OF THE INDIAN TERRITORY by Jenna Hunnef A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Jenna Hunnef 2016 Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory Jenna Hunnef Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2016 Abstract In this dissertation, I examine how literary representations of outlaws and outlawry have contributed to the shaping of national identity in the United States. I analyze a series of texts set in the former Indian Territory (now part of the state of Oklahoma) for traces of what I call “outlaw rhetorics,” that is, the political expression in literature of marginalized realities and competing visions of nationhood. Outlaw rhetorics elicit new ways to think the nation differently—to imagine the nation otherwise; as such, I demonstrate that outlaw narratives are as capable of challenging the nation’s claims to territorial or imaginative title as they are of asserting them. Borrowing from Abenaki scholar Lisa Brooks’s definition of “nation” as “the multifaceted, lived experience of families who gather in particular places,” this dissertation draws an analogous relationship between outlaws and domestic spaces wherein they are both considered simultaneously exempt from and constitutive of civic life. In the same way that the outlaw’s alternately celebrated and marginal status endows him or her with the power to support and eschew the stories a nation tells about itself, so the liminality and centrality of domestic life have proven effective as a means of consolidating and dissenting from the status quo of the nation-state. -

Pottery Pieces Designed & Handmade in Our Ceramic Studios and Fired in Our Kilns

GLAZES ACCESSORIES FOUNTAINS PLANTERS & URNS OIL JARS ORNAMENTAL PIECES BIRDBATHS INTRODUCTION TERY est. 1875 Gladding, McBean & Co. POT Over A Century Of Camanship In Clay INTRODUCTION artisan made This catalog shows the wide range of pottery pieces designed & handmade in our ceramic studios and fired in our kilns. These pieces are not only for the garden, but also for general use of decoration indoors and out. Gladding, McBean & Co. has been producing this pottery for 130 years. Its manufacture began in the earliest years of the company’s existence at a time when no other terra cotta plant on the Pacific Coast was attempting anything of the sort. Gladding, McBean & Co. therefore, has pioneered in pottery-making. The company feels that it has carried the art to an impressive height of excellence. In every detail but color the following photographs speak for themselves. Each piece is glazed in one of our beautiful proprietary glazes. A complete set of glaze samples can be seen at our retail showrooms. This pottery is on display at, and may be ordered from, any of the retail showrooms listed on our website at www.gladdingmcbean.com. In photographing the pieces, and in reproducing the photographs for this catalog, the strictist care was taken to make the pictures as faithful as possible to the objects themselves. We are confident that in every instance the pottery will be found lovelier than its picture. The poet might well have had this pottery in mind when he wrote: “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.” BIRDBATHS no. 1099 birdbath width: 15.5” height: 24.5” base: 10” Birdbath no. -

2013 Trail News

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Trail News Enthusiastic Groups Attend Preservation Workshops Large groups and enthusiastic properties, to seek help in identifying valuable preservation expertise from participation characterized two recently- previously unknown historic buildings representatives of three State Historic held Trail of Tears National Historic Trail along the trail routes, and to set priorities Preservation Ofces (SHPOs). Mark (NHT) preservation workshops. The among chapter members for actions Christ and Tony Feaster spoke on behalf frst took place in Cleveland, Tennessee, to be taken related toward historic site of the Arkansas Historic Preservation on July 8 and 9, while the second took identifcation and preservation. Program, and Lynda Ozan—who also place on July 12 and 13 in Fayetteville, attended the Fayetteville meeting— Arkansas. More than 80 Trail of Tears To assist association members in represented the Oklahoma SHPO. At Association (TOTA) members and expanding the number of known historic the Cleveland meeting, Peggy Nickell friends attended the workshops, which sites along the trail, the NPS has been represented the Tennessee SHPO. TOTA took place as a result of the combined working for the past year with the Center President Jack Baker, recently elected to eforts of the Trail of Tears Association, for Historic Preservation at Middle the Cherokee Nation’s Tribal Council, the National Park Service (NPS), and Tennessee State University. Two staf played a key leadership role at both Middle Tennessee State University in members from the center, Amy Kostine workshops. Murphreesboro. and Katie Randall, were on hand at both workshops, and each shared information Representatives of both the Choctaw The workshops had several purposes: to on what had been learned about newly- and Chickasaw nations were also in provide information about historic sites discovered trail properties. -

United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Hosts Keetoowah Cherokee Language Classes Throughout the Tribal Jurisdictional Area on an Ongoing Basis

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: United Keetoowah (ki-tu’-wa ) Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Tribal website(s): www.keetoowahcherokee.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” Original Homeland Archeologists say that Keetoowah/Cherokee families began migrating to a new home in Arkansas by the late 1790's. A Cherokee delegation requested the President divide the upper towns, whose people wanted to establish a regular government, from the lower towns who wanted to continue living traditionally. On January 9, 1809, the President of the United States allowed the lower towns to send an exploring party to find suitable lands on the Arkansas and White Rivers. Seven of the most trusted men explored locations both in what is now Western Arkansas and also Northeastern Oklahoma. The people of the lower towns desired to remove across the Mississippi to this area, onto vacant lands within the United States so that they might continue the traditional Cherokee life. -

1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

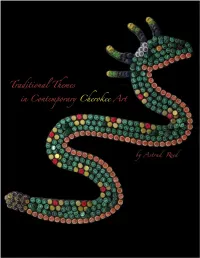

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword "What About Indian Art?" An Interview with Dr. Mary Jo Watson Director, School of Art and Art History / Regents Professor of Art History KGOU Radio Interview by Brant Morrell • April 17, 2013 Twenty years ago, a degree in Native American Art and Art History was non-existent. Even today, only a few universities offer Native Art programs, but at the University of Oklahoma Mary Jo Watson is responsible for launching a groundbreaking art program with an emphasis on the indigenous perspective. You expect a director of an art program at a major university to have pieces in their office, but entering Watson’s workspace feels like stepping into a Native art museum. -

Cherokee Pottery

Ewf gcQl q<HhJJ Cherokee Pottery a/xW n A~ aGw People of One Fire D u n c a n R i g g s R o d n i n g Y a n t z ISBN: 0-9742818-2-4 Text by:Barbara Duncan, Brett H. Riggs, Christopher B. Rodning and I. Mickel Yantz, Design and Photography, unless noted: I. Mickel Yantz Copyright © 2007 Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc PO Box 515, Tahlequah, Oklahoma 74465 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage system or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Cover: Arkansas Applique’ by Jane Osti, 2005. Cherokee Heritage Center Back Cover: Wa da du ga, Dragonfly by Victoria McKinney, 2007; Courtesy of artist. Right: Fire Pot by Nancy Enkey, 2006; Courtesy of artist. Ewf gcQl q<HhJJ Cherokee Pottery a/xW n A~ aGw People of One Fire Dr. Barbara Duncan, Dr. Brett H. Riggs, Christopher B. Rodning, and I. Mickel Yantz Cherokee Heritage Center Tahlequah, Oklahoma Published by Cherokee Heritage Press 2007 3 Stamped Pot, c. 900-1500AD; Cherokee Heritage Center 2, Cherokee people who have been living in the southeastern portion of North America have had a working relationship with the earth for more than 3000 years. They took clay deposits from the Smokey Mountains and surrounding areas and taught themselves how to shape, decorate, mold and fire this material to be used for utilitarian, ceremonial and decorative uses. -

The Lost Arts Project - 1988

The Lost Arts Project - 1988 The Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. and the Cherokee Nation partnered in 1988 to create the Lost Arts Program focusing on the preservation and revival of cultural arts. A new designation was created for Master Craftsmen who not only mastered their art, but passed their knowledge on to the next generation. Stated in the original 1988 brochure: “The Cherokee people are at a very important time in history and at a crucial point in making provisions for their future identity as a distinct people. The Lost Arts project is concerned with the preservation and revival of Cherokee cultural practices that any be lost in the passage from one generation to another. The project is concerned with capturing the knowledge, techniques, individual commitment available to us and heritage received from Cherokee folk artists and developing educational and cultural preservation programs based on their knowledge and experience.” Artists had to be Cherokee and nominated by at least two people in the community. When selected, they were designated as “Living National Treasures.” 24 1 Do you know these Treasures? Lyman Vann - 1988 Bow Making Mattie Drum - 1990 Weaving Rogers McLemore - 1990 Weaving Hester Guess - 1990 Weaving Sally Lacy - 1990 Weaving Stella Livers - 1990 Basketry Eva Smith - 1991 Turtle Shell Shackles Betty Garner - 1993 Basketry Vivian Leaf Bush -1993 Turtle Shell Shackles David Neugin - 1994 Bow Making Vivian Elaine Waytula - 1995 Basketry Richard Rowe 1996 Carving Lee Foreman - 1999 Marble Making Original Lost Arts Program Exhibit Flyer- 1988 Mildred Justice Ketcher - 1999 Basketry Albert Wofford - 1999 Gig Making/Carving Willie Jumper - 2001 Stickball Sticks Sam Lee Still - 2002 Carving Linda Mouse-Hansen - 2002 Basketry Unfortunately, we have not been able to locate information, pictures or examples of art from the following Treasures. -

ROM Exhibitions

Exhibition Database chronology Opening Date Exhibition Title Closing Date Locator [yyyy-mm-dd] [yyyy-mm-dd] Group Box 1934 Sir Edmund Walker's Collection of Japanese Prints 1935 Books Connected with Museum Work 1935 Harry Wearne Collection of Textiles 1935-05-16 Society of Canadian Painter-Etchers and Engravers 1935-05-29RG107 1 1936-02-17 Canadian Ceramic Association 1936-02-18RG107 1 1938 Australian Shells 1938 Tropical Butterflies and Moths 1938 Aquarium Show 1938 Nature Projects by Children 1938 Wild-Life Photographs 1938-spring Canadian Guild of Potters RG107 1 1939 Exhibit of Summer's Field Expedition's Finds 1939 Reproductions of Audubon's Bird Paintings 1939 Nature Photographs by Local Naturalist Photographers 1939 Works of Edwards and Catesby 1939 Natural History Notes and Publications of Charles Fothergill September 5, 2012 Page 1 of 67 Opening Date Exhibition Title Closing Date Locator [yyyy-mm-dd] [yyyy-mm-dd] Group Box 1941-03-21 Our War Against Insects 1941-04-02RG107 1 1941-04-06 Tropical Aquarium Fish 1941-06-20RG107 1 1942 Strategic Minerals 1942 Twelfth Century Chinese Porcelains 1942 Prospector's Guide for Strategic Minerals in Canada 1942-09 Cockburn Watercolours 1942-10 1942-10-24 Chinese Painting 1942-10-28RG107 1 1942-11 Hogarth Prints 1942-12 1942-summer Canadian Prints 1943 Minerals from Ivigtut, Greenland 1943 Introducing New Britain & New Ireland RG107 1 1943-01 History of Prints 1943-02 1943-03-06 Society of Canadian Painter-Etchers and Engravers 1943-04-04RG107 1 1943-04 Piranesi 1943-05 1943-06 Uses of Printing -

Making Beaded Jewelry 11 Free Seed Bead Patterns and Projects Ebook

Making Beaded Jewelry: 11 Free Seed Bead Patterns and Projects Copyright © 2012 by Prime Publishing, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Trademarks are property of their respective holders. When used, trademarks are for the benefit of the trademark owner only. Published by Prime Publishing LLC, 3400 Dundee Road, Northbrook, IL 60062 – www.primecp.com Free Jewelry Making Projects Free Craft Projects Free Knitting Projects Free Quilt Projects Free Sewing Projects Free Crochet Afghan Patterns Free Christmas Crafts Free Crochet Projects Free Holiday Craft Projects Free DIY Wedding Ideas Free Kids’ Crafts Free Paper Crafts 11 Free Seed Bead Patterns and Projects Letter from the Editors Hey beading buddies, Confession time: How many of you have an overflowing supply of seed beads? It’s OK; we’re all guilty. It’s the mark of a true beader! But every once in a while, you need to clear out the seed bead stash (before it threatens to bury you alive), right? Well with that in mind, we’ve collected 11 amazing seed bead jewelry patterns and projects to help you keep your bead hoarding tendencies at bay! From stunning necklaces, to fabulous earrings, and with plenty of gorgeous cuffs and bracelets in between, we’ve got all the jewelry patterns you need to say “Sayonara!” to that infinite seed bead abyss that is currently swallowing your craft room. -

Wampum Belts Were Used to Record Events and Memories

Wampum belts were used to record events and memories. The use of patterns and symbols were a method of storytelling. Lesson : WAMPUM UNIT PRE-VISIT SUGGESTIONS Discuss with students the context for Wampum. Ask students “Do you have an article of clothing that commemorates an event or vacation?” Note: this item may or may not contain the description of time, date, and place, but still holds the memorial significance. Have students bring in an object of memorial significance, but not something of great value, to show how the individual brings significance to otherwise ordinary objects. Wampum belts Keywords & Vocabulary quahog - a bivalve mollusk, a hard clam, native to North America’s Atlantic coast that was prized for the purple interior part of the shell, used to make purple wampum. whelk - a marine gastropod (snail-like with a hard shell) whose shell was used to make the white beads for wampum. wampum - purple and white shell beads strung together in patterns or on a ‘belt’ used to record events and memories used by American Indians of the Eastern Woodlands. Guiding Questions What meaning did wampum have for American Indians? What materials were used? Grade Ranges K-2 students use a coloring page with pattern of wampum and tell a story Quahog shells 3-6 students design a wampum belt on graph paper and use it to tell a story Differentiated Instruction 7-12 students design a wampum belt on graph As needed for less able, students will be paired to paper and use it to tell a story facilitate activity success.