Selected Students of Leopold Auer: a Study in Violin Performance-Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

La Société Philharmonique

The Historic New Orleans Collection & Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra Carlos Miguel Prieto Adelaide Wisdom Benjamin Music Director and Principal Conductor Pr eseNT Identity, History, Legacy La Société PhiLh ar monique Thomas Wilkins, conductor Walter Harris Jr., speaker Kisma Jordan, soprano Joseph Meyer, violin Jean-Baptiste Monnot, organ/piano Phumzile Sojola, tenor THursday, February 10, 2011 Cathedral-basilica of st. Louis, King of France New Orleans, Louisiana Fr Iday, February 11, 2011 slidell High school slidell, Louisiana The Historic New Orleans Collection and the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra gratefully acknowledge rev. Msgr. Crosby W. Kern and the staff of the st. Louis Cathedral for their generous support and assistance. The musical culture of New Orleans’s free people of color and their descendants is one of the most extraordinary aspects of Louisiana history, and it is part of a larger, shared legacy. Only within the context of the development of african music in the New World can the contributions of these sons and daughters of Louisiana be fully appreciated. The first africans arrived in the New World with the initial wave of spanish colonization in the early sixteenth century. Interactions among european, african, and indigenous populations yielded new forms of cultural expression—although african music in the New World remained strongly dependent on wind instruments (such as ivory trumpets), drums, and call-and-response patterns. as early as 1572, africans were gathering in front of the famous aztec calendar stone in Mexico City on sunday afternoons to dance and sing. When Viceroy antonio de Mendoza triumphantly entered Lima on august 31, 1551, his procession’s route was lined with african drummers. -

Locatelli, Campagnoli, Ernst: Three Composers Under Paganini's Shadow

Fine Arts International Journal Srinakharinwirot University Vol. 15 No. 1 January - June 2011 Violin Recital The Unknown Violin Virtuoso - Locatelli, Campagnoli, Ernst: three composers under Paganini’s shadow. Mathias Boegner Department of Western Music Faculty of Fine Arts, Srinakharinwirot University, Thailand Corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] Introduction In modern violin pedagogy we are aware Recently I followed two recommendations of skills and achievements from a few hundred from teachers and colleagues: From the famous years – nevertheless, various features are more pedagogue Prof. Max Rostal in Switzerland, well-known or famous than others, regardless to practice the Divertimenti by Campagnoli, their actual importance and impact. With all to improve safer intonation; and from my Italian respect to our great and unique icon Paganini, colleague Prof. Enzo Porta, to look for the some insight has been ascribed to his personality Caprices by Locatelli, in search for the so-called while in fact some of his colleagues found those “Labyrinth” in David Oistrakh’s performance. roots: Pietro Locatelli, one of the three violinist- My third third issue is the practicing of the works composers focused on here, has included the by Ernst, for climbing and challenging the violin complete demands of Paganini’s Caprices op.1 skills. in his own Caprices op. 3, long before Paganini 2 Fine Arts International Journal, Srinakharinwirot University was born. This concludes that the modernization II) His works and style of the violin building and the Tourte bow at III) The “Art of the Violin”, 24 Caprices Paganini’s time basically did not have to do with op. -

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER the CANOPY of MY LIFE Artistic, Creative, Musical Pedagogy, Public and Private

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER THE CANOPY OF MY LIFE Artistic, creative, musical pedagogy, public and private Translated by John Ranck But1 you are getting old, pick Flowers, growing on the graves And with them renew your heart. Nekrasov2 And ethereally brightening-within-me Beloved shadows arose in the Argentine mist Balmont3 The Tcherepnins are from the vicinity of Izborsk, an ancient Russian town in the Pskov province. If I remember correctly, my aged aunts lived on an estate there which had been passed down to them by their fathers and grandfathers. Our lineage is not of the old aristocracy, and judging by excerpts from the book of Records of the Nobility of the Pskov province, the first mention of the family appears only in the early 19th century. I was born on May 3, 1873 in St. Petersburg. My father, a doctor, was lively and very gifted. His large practice drew from all social strata and included literary luminaries with whom he collaborated as medical consultant for the gazette, “The Voice” that was published by Kraevsky.4 Some of the leading writers and poets of the day were among its editors. It was my father’s sorrowful duty to serve as Dostoevsky’s doctor during the writer’s last illness. Social activities also played a large role in my father’s life. He was an active participant in various medical societies and frequently served as chairman. He also counted among his patients several leading musical and theatrical figures. My father was introduced to the “Mussorgsky cult” at the hospitable “Tuesdays” that were hosted by his colleague, Dr. -

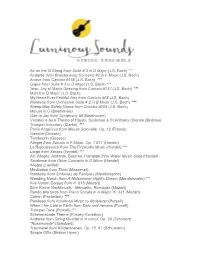

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S. Bach) Arioso from Cantata #156 (J.S. Bach) *** Gigue from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring from Cantata #147 (J.S. Bach) *** March in D Major (J.S. Bach) My Heart Ever Faithful Aria from Cantata #68 (J.S. Bach) Rondeau from Orchestral Suite # 2 in B Minor (J.S. Bach) *** Sheep May Safely Graze from Cantata #208 (J.S. Bach) Minuet in G (Beethoven) Ode to Joy from Symphony #9 (Beethoven) Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Sicilienne & St Anthony Chorale (Brahms) Trumpet Voluntary (Clarke) *** Panis Angelicus from Messe Solonelle, Op. 12 (Franck) Gavotte (Gossec) Tambourin (Gossec) Allegro from Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 #11 (Handel) La Rejouissance from The Fireworks Music (Handel) *** Largo from Xerxes (Handel) *** Air, Allegro, Andante, Bourree, Hornpipe from Water Music Suite (Handel) Sarabane from Oboe Concerto in G Minor (Handel) Allegro (Loeillet) Meditation from Thais (Massenet) Rondeau from Sinfonies de Fanfares (Mendelssohn) Wedding March from A Midsummer Night's Dream (Mendelssohn) *** Ave Verum Corpus from K. 618 (Mozart) Eine Kleine Nachtmusik - Menuetto, Romanza (Mozart) Rondo alla turca from Piano Sonata in A Major, K. 331 (Mozart) Canon (Pachelbel) *** Rondeau from Incidental Music to Abdelazer (Purcell) When I Am Laid in Earth from Dido and Aeneas (Purcell) Trumpet Tune (Purcell) *** Scheherazade Theme (Rimsky-Korsakov) Andante from String Quartet in A minor, Op. 29 (Schubert) "Rosamunde" (Schubert) Traumerei from Kinderscenen, Op. 15, #7 (Schumann) Simple Gifts (Shaker Hymn) Presto from Sonatina in F Major (Telemann) Vivace from Sonata in F Major for flute (Telemann) Be Thou My Vision (Traditional Irish Melody) Danza Pastorale from Violin Concerto in E Major, Op. -

Maud Powell As an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 "The Solution Lies with the American Women": Maud Powell as an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C. Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC “THE SOLUTION LIES WITH THE AMERICAN WOMEN”: MAUD POWELL AS AN ADVOCATE FOR VIOLINISTS, WOMEN, AND AMERICAN MUSIC By CATHERINE C. WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Catherine C. Williams defended this thesis on May 9th, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Thesis Michael Broyles Committee Member Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Maud iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my brother, Mary Ann, Geoff, and Grant, for their unceasing support and endless love. My entire family deserves recognition, for giving encouragement, assistance, and comic relief when I needed it most. I am in great debt to Tristan, who provided comfort, strength, physics references, and a bottomless coffee mug. I would be remiss to exclude my colleagues in the musicology program here at The Florida State University. The environment we have created is incomparable. To Matt DelCiampo, Lindsey Macchiarella, and Heather Paudler: thank you for your reassurance, understanding, and great friendship. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 65,1945-1946

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 SIXTY-FIFTH SEASON, 1945-1946 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, I945, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, ItlC. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot . President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. Be Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Bentley W. Warren N. Penrose Hallowell Oliver Wolcott G. E. Judd, Manager [453 1 ®**65 © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © Time for Revi ew ? © © Are your plans for the ultimate distribu- © © tion of your property up-to-date? Changes © in your family situation caused by deaths, © births, or marriages, changes in the value © © of your assets, the need to meet future taxes © . these are but a few of the factors that © suggest a review of your will. © We invite you and your attorney to make © use of our experience in property manage- © ment and settlement of estates by discuss- © program with our Trust Officers. © ing your © © PERSONAL TRUST DEPARTMENT © © The V^Cational © © © Shawmut Bank © Street^ Boston © 40 Water © Member Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation © Capital % 10,000,000 Surplus $20,000,000 © "Outstanding Strength" for 108 Years © © © ^oHc^;c^oH(§@^a^^^aa^aa^^@^a^^^^^©©©§^i^ SYMPHONIANA Musical Exposure Exhibition MUSICAL EXPOSURE Among the chamber concerts organ- ized by members of this orchestra, there is special interest in the venture of the Zimbler String Quartet. Augmented by a flute, clarinet, or harpsichord, they are acquainting the pupils of high schools with this kind of music. -

FONDO BAR CONSERVAZ 4 Parti Separate DOCUMENTO PER SOLA CONSULTAZIONE INTERNA

ELENCO DELLE NOTIZIE RISULTANTI DALLA RICERCA BIBLIOGRAFICA 1. er Quatuor pour 2 violons, alto et violoncelle : Op.10 / Claude Debussy . - [Parties]. - Paris : Durande & Fils, [s.d.]. - 4 parti (15 p.) ; 32 p. ((Dati bibliografici dalla prima pagina di musica. N.Inv.: 18658 MUSICA FONDO BAR CONSERVAZ 4 parti separate DOCUMENTO PER SOLA CONSULTAZIONE INTERNA 1. Vonosnegyes / Bela Bartok ; ellenoritze D. Dille. - [Szolamok]. - Budapest : Editio Musica, ©1956. - 4 parti (11 p.) ; 31 p. ((Dati bibliografici dalla copartina e dalle prima pagina di musica. N.Inv.: 18657 MUSICA FONDO BAR MC 0017 4 parti separate 1. Vonosnegyes : Op. 7 / Bartok Bela ; ellenoritze D. Dille. - [Partitura]. - Budapest : Editio Musica, ©1950. - 1 partiturina (39 p.) ; 20 cm. N.Inv.: 18656 MUSICA FONDO BAR MC 0016 1 partitura 10 Kunstler-Etuden fur Viola Op. 44 / von Johannes Palaschko . - Frankfurt am Main : Zimmermann, ©1965. - 29 p. ; 31 cm. N.Inv.: 18622 MUSICA FONDO BAR VA 0012 1 v. di musica a stampa DOCUMENTO PER SOLA CONSULTAZIONE INTERNA 12 studi op. 62 per viola / Johannes Palaschko . - Milano [etc.] : Ricordi, ©1923. - 21 p. ; 32 cm. ((Data di ripristino 1956. N.Inv.: 18624 MUSICA FONDO BAR VA 0013 1 v. di musica a stampa 12 studi per viola / Marco Anzoletti . - Milano [etc.] : Ricordi, ©1919. - 42 p. ; 32 cm. ((Dati bibliografici dal frontespizio e dalla prima pagina di musica. N.Inv.: 18614 MUSICA FONDO BAR VA 0014 1 v. di musica a stampa 19 Studi per violino / Kreutzer ; (Abbado). - Milano [etc.] : Ricordi, ©1955. - 20 p. ; 32 cm. N.Inv.: 18707 MUSICA FONDO BAR VL 0011 1 v. di musica a stampa 1er Grand Concerto pour piano et violon : Op. -

Sir Hamilton Harty Music Collection

MS14 Harty Collection About the collection: This is a collection of holograph manuscripts of the composer and conductor, Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) featuring full and part scores to a range of orchestral and choral pieces composed or arranged by Harty, c 1900-1939. Included in the collection are arrangements of Handel and Berlioz, whose performances of which Harty was most noted, and autograph manuscripts approx. 48 original works including ‘Symphony in D (Irish)’ (1915), ‘The Children of Lir’ (c 1939), ‘In Ireland, A Fantasy for flute, harp and small orchestra’ and ‘Quartet in F for 2 violins, viola and ‘cello’ for which he won the Feis Ceoil prize in 1900. The collection also contains an incomplete autobiographical memoir, letters, telegrams, photographs and various typescript copies of lectures and articles by Harty on Berlioz and piano accompaniment, c 1926 – c 1936. Also included is a set of 5 scrapbooks containing cuttings from newspapers and periodicals, letters, photographs, autographs etc. by or relating to Harty. Some published material is also included: Performance Sets (Appendix1), Harty Songs (MS14/11). The Harty Collection was donated to the library by Harty’s personal secretary and intimate friend Olive Baguley in 1946. She was the executer of his possessions after his death. In 1960 she received an honorary degree from Queen’s (Master of Arts) in recognition of her commitment to Harty, his legacy, and her assignment of his belongings to the university. The original listing was compiled in various stages by Declan Plumber -

Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 Although the dating of Bach’s four orchestral suites is uncertain, the third was probably written in 1731. The score calls for two oboes, three trumpets, timpani, and harpsichord, with strings and basso continuo. Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Sympho ny Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite were given at the Auditorium Theatre on October 23 and 24, 1891, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15 , 16, 17, and 20, 2003, with Jaime Laredo conducting. The Orchestra first performed the Air and Gavotte from this suite at the Ravinia Festival on June 29, 1941, with Frederick Stock conducting; the complete suite was first performed at Ravinia on August 5 , 1948, with Pierre Monteux conducting, and most recently on August 28, 2000, with Vladimir Feltsman conducting. When the young Mendelssohn played the first movement of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite on the piano for Goethe, the poet said he could see “a p rocession of elegantly dressed people proceeding down a great staircase.” Bach’s music was nearly forgotten in 1830, and Goethe, never having heard this suite before, can be forgiven for wanting to attach a visual image to such stately and sweeping music. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers and when these four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks.