Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnificat in D Major, BWV

Johann Sebastian Bach Magnificat in D Major, BWV 243 Magnificat Quia respexit Quia fecit mihi magna Et misericordia eius Fecit potentiam Deposuit potentes Suscepit Israel Gloria patri Sicut erat in principio *** Chorus: S-S-A-T-B Soloists: Soprano 1, soprano 2, alto, tenor, bass Orchestra: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 oboes d'amore, 3 trumpets, timpani, strings, continuo ************************* Program notes by Martin Pearlman Bach, Magnificat, BWV 243 In 1723, for his first Christmas as cantor of the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Bach presented a newly composed setting of the Magnificat. It was a grand, celebratory work with a five-voice chorus and a colorful variety of instruments, and Bach expanded the Magnificat text itself by interpolating settings of several traditional Christmas songs between movements. This was the original Eb-major version of his Magnificat, and it was Bach's largest such work up to that point. About a decade later, he reworked the piece, lowering the key from Eb to the more conventional trumpet key of D major, altering some of the orchestration, and, perhaps most importantly, removing the Christmas inserts, so that the work could be performed at a variety of festivals during the liturgical year. It is this later D major version of the Magnificat that is normally heard today. Despite its brilliance and grandeur, Bach's Magnificat is a relatively short work. Nonetheless, it is filled with countless fascinating details. The tenor opens his aria Deposuit with a violent descending F# minor scale to depict the text "He hath put down [the mighty]". At the end of the alto aria Esurientes, Bach illustrates the words "He hath sent the rich away empty" by having the solo flutes omit their final note. -

574040-41 Itunes Beethoven

BEETHOVEN Chamber Music Piano Quartet in E flat major • Six German Dances Various Artists Ludwig van ¡ Piano Quartet in E flat major, Op. 16 (1797) 26:16 ™ I. Grave – Allegro ma non troppo 13:01 £ II. Andante cantabile 7:20 BEE(1T77H0–1O827V) En III. Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo 5:54 1 ¢ 6 Minuets, WoO 9, Hess 26 (c. 1799) 12:20 March in D major, WoO 24 ‘Marsch zur grossen Wachtparade ∞ No. 1 in E flat major 2:05 No. 2 in G major 1:58 2 (Grosser Marsch no. 4)’ (1816) 8:17 § No. 3 in C major 2:29 March in C major, WoO 20 ‘Zapfenstreich no. 2’ (c. 1809–22/23) 4:27 ¶ 3 • No. 4 in F major 2:01 4 Polonaise in D major, WoO 21 (1810) 2:06 ª No. 5 in D major 1:50 Écossaise in D major, WoO 22 (c. 1809–10) 0:58 No. 6 in G major 1:56 5 3 Equali, WoO 30 (1812) 5:03 º 6 Ländlerische Tänze, WoO 15 (version for 2 violins and double bass) (1801–02) 5:06 6 No. 1. Andante 2:14 ⁄ No. 1 in D major 0:43 No. 2 in D major 0:42 7 No. 2. Poco adagio 1:42 ¤ No. 3. Poco sostenuto 1:05 ‹ No. 3 in D major 0:38 8 › No. 4 in D minor 0:43 Adagio in A flat major, Hess 297 (1815) 0:52 9 fi No. 5 in D major 0:42 March in B flat major, WoO 29, Hess 107 ‘Grenadier March’ No. -

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

UWM Department of Music Concert Program Style Guide

UWM Department of Music Concert Program Style Guide Table of Contents 1. General Rules for All Titles 2. Generic Titles 3. Distinctive Titles 4. Composer Names & Dates 1. General Rules for All Titles 1.1 Titles (including movement titles) are capitalized following the rules of each language: a. English: capitalize all words except conjunctions, prepositions, and articles, unless they begin a title. b. French: capitalize all words up to and including the first noun; everything after that is lower case (except for proper nouns). c. German: capitalize first word, and all nouns. d. Italian & Spanish: capitalize first word, all else is lower case except proper nouns. 1.2 Movement Titles a. Movements follow under the main title; those in foreign languages should be italicized. b. Movement numbers are uppercase roman numerals (I, II, III, IV, rather than i, ii, iii, iv) c. If all movements of a work are performed in order, they do not need to be numbered; otherwise number the movements being performed with their original numbers. If only a few movements of many are being performed, it is possible to also add the word “Selections” in parentheses after the title to avoid confusion. Examples: Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 V. Bourrée VI. Gigue Carnaval des animaux (Selections) IV. Tortues XII. Fossiles d. It is appropriate to translate movement titles that might not otherwise be understood, particularly if they are not translated elsewhere in the program. Place translation(s) in parentheses. Example: Concerto for Orchestra I. Introduzione II. Gioco delle coppie (Game of Pairs) III. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Ausgewählte Werke

Gottfried August Homilius Ausgewählte Werke Reihe 4: Instrumentalwerke Band 2 herausgegeben von Uwe Wolf In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Bach-Archiv Leipzig Gottfried August Homilius 32 Praeludia zu geistlichen Liedern für zwei Claviere und Pedal Choralvorspiele für Orgel herausgegeben von Uwe Wolf Urtext 37.107 Vorwort […] Im nachmittäglichen Gottesdienste wurden 3 Lieder gesungen, und der seelige Mann hatte es sich zum Gesetz gemacht, allemal drey Gottfried August Homilius wurde am 2. Februar 1714 in Rosenthal verschiedene Vorspiele, auf die er sich den Sonnabend vorher sorgfältig vorbereitete, zu den 3 Liedern zu machen. […] Alle Musikkenner und (Sachsen) als Sohn eines Pastors geboren. Bereits kurz nach seiner Liebhaber versammelten sich Nachmittags in der Kirche, um diese Prälu- Geburt zog die Familie nach Porschendorf bei Pirna, wo Homilius dien zu hören, und Homilius erwarb sich damit den Ruhm eines großen, die ersten Jahre seines Lebens verbrachte.1 Nach dem Tod des Vaters selbst des größten Organisten seiner Zeit, wenn man Erfindung und Ge- wechselte er 1722 – wohl auf Betreiben seiner Mutter – an die von schmack mit in Anschlag bringt.7 deren Bruder geleitete Annenschule nach Dresden. Gegen Ende seiner Schulzeit übernahm Homilius bereits vertretungsweise den Von Daniel Gottlob Türk, einem anderen Schüler Homilius’, erfah- Organistendienst an der Annen-Kirche. ren wir, dass die erwähnte sorgfältige Vorbereitung tatsächlich im Im Mai 1735 wurde Homilius als Jurastudent an der Universität schriftlichen Fixieren der Praeludien bestand, -

Key Relationships in Music

LearnMusicTheory.net 3.3 Types of Key Relationships The following five types of key relationships are in order from closest relation to weakest relation. 1. Enharmonic Keys Enharmonic keys are spelled differently but sound the same, just like enharmonic notes. = C# major Db major 2. Parallel Keys Parallel keys share a tonic, but have different key signatures. One will be minor and one major. D minor is the parallel minor of D major. D major D minor 3. Relative Keys Relative keys share a key signature, but have different tonics. One will be minor and one major. Remember: Relatives "look alike" at a family reunion, and relative keys "look alike" in their signatures! E minor is the relative minor of G major. G major E minor 4. Closely-related Keys Any key will have 5 closely-related keys. A closely-related key is a key that differs from a given key by at most one sharp or flat. There are two easy ways to find closely related keys, as shown below. Given key: D major, 2 #s One less sharp: One more sharp: METHOD 1: Same key sig: Add and subtract one sharp/flat, and take the relative keys (minor/major) G major E minor B minor A major F# minor (also relative OR to D major) METHOD 2: Take all the major and minor triads in the given key (only) D major E minor F minor G major A major B minor X as tonic chords # (C# diminished for other keys. is not a key!) 5. Foreign Keys (or Distantly-related Keys) A foreign key is any key that is not enharmonic, parallel, relative, or closely-related. -

Allemande Johann Herrmann Schein Sheet Music

Allemande Johann Herrmann Schein Sheet Music Download allemande johann herrmann schein sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of allemande johann herrmann schein sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 4280 times and last read at 2021-09-29 13:16:38. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of allemande johann herrmann schein you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Bassoon Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Canzon No 23 A Baroque Madrigal By Johann Hermann Schein For Brass Quintet Canzon No 23 A Baroque Madrigal By Johann Hermann Schein For Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 3565 times. Canzon no 23 a baroque madrigal by johann hermann schein for brass quintet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 17:32:11. [ Read More ] Allemande From The French Suite Number V By Johann Sebastian Bach Arranged For 3 Woodwinds Allemande From The French Suite Number V By Johann Sebastian Bach Arranged For 3 Woodwinds sheet music has been read 3664 times. Allemande from the french suite number v by johann sebastian bach arranged for 3 woodwinds arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-29 13:16:24. [ Read More ] Hinunter Ist Der Sonne Schein Fr Posaunenquartett Hinunter Ist Der Sonne Schein Fr Posaunenquartett sheet music has been read 3235 times. -

Harpsichord Suite in a Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet De La Guerre

Harpsichord Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre Arranged for Solo Guitar by David Sewell A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Frank Koonce, Chair Catalin Rotaru Kotoka Suzuki ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2019 ABSTRACT Transcriptions and arrangements of works originally written for other instruments have greatly expanded the guitar’s repertoire. This project focuses on a new arrangement of the Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729), which originally was composed for harpsichord. The author chose this work because the repertoire for the guitar is critically lacking in examples of French Baroque harpsichord music and also of works by female composers. The suite includes an unmeasured harpsichord prelude––a genre that, to the author’s knowledge, has not been arranged for the modern six-string guitar. This project also contains a brief account of Jacquet de la Guerre’s life, discusses the genre of unmeasured harpsichord preludes, and provides an overview of compositional aspects of the suite. Furthermore, it includes the arrangement methodology, which shows the process of creating an idiomatic arrangement from harpsichord to solo guitar while trying to preserve the integrity of the original work. A summary of the changes in the current arrangement is presented in Appendix B. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to Professor Frank Koonce for his support and valuable advice during the development of this research, and also to the members of my committee, Professor Catalin Rotaru and Dr. -

Bach and Money: Sources of Salary and Supplemental Income in Leipzig from 1723 to 1750*

Understanding Bach, 12, 111–125 © Bach Network UK 2017 Young Scholars’ Forum Bach and Money: Sources of Salary and Supplemental Income in Leipzig * from 1723 to 1750 NOELLE HEBER It was his post as Music Director and Cantor at the Thomasschule that primarily marked Johann Sebastian Bach’s twenty-seven years in Leipzig. The tension around the unstable income of this occupation drove Bach to write his famous letter to Georg Erdmann in 1730, in which he expressed a desire to seek employment elsewhere.1 The difference between his base salary of 100 Thaler and his estimated total income of 700 Thaler was derived from legacies and foundations, funerals, weddings, and instrumental maintenance in the churches, although many payment amounts fluctuated, depending on certain factors such as the number of funerals that occurred each year. Despite his ongoing frustration at this financial instability, it seems that Bach never attempted to leave Leipzig. There are many speculations concerning his motivation to stay, but one could also ask if there was a financial draw to settling in Leipzig, considering his active pursuit of independent work, which included organ inspections, guest performances, private music lessons, publication of his compositions, instrumental rentals and sales, and, from 1729 to 1741, direction of the collegium musicum. This article provides a new and detailed survey of these sources of revenue, beginning with the supplemental income that augmented his salary and continuing with his freelance work. This exploration will further show that Leipzig seems to have been a strategic location for Bach to pursue and expand his independent work. -

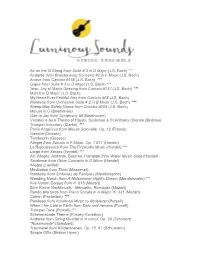

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S. Bach) Arioso from Cantata #156 (J.S. Bach) *** Gigue from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring from Cantata #147 (J.S. Bach) *** March in D Major (J.S. Bach) My Heart Ever Faithful Aria from Cantata #68 (J.S. Bach) Rondeau from Orchestral Suite # 2 in B Minor (J.S. Bach) *** Sheep May Safely Graze from Cantata #208 (J.S. Bach) Minuet in G (Beethoven) Ode to Joy from Symphony #9 (Beethoven) Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Sicilienne & St Anthony Chorale (Brahms) Trumpet Voluntary (Clarke) *** Panis Angelicus from Messe Solonelle, Op. 12 (Franck) Gavotte (Gossec) Tambourin (Gossec) Allegro from Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 #11 (Handel) La Rejouissance from The Fireworks Music (Handel) *** Largo from Xerxes (Handel) *** Air, Allegro, Andante, Bourree, Hornpipe from Water Music Suite (Handel) Sarabane from Oboe Concerto in G Minor (Handel) Allegro (Loeillet) Meditation from Thais (Massenet) Rondeau from Sinfonies de Fanfares (Mendelssohn) Wedding March from A Midsummer Night's Dream (Mendelssohn) *** Ave Verum Corpus from K. 618 (Mozart) Eine Kleine Nachtmusik - Menuetto, Romanza (Mozart) Rondo alla turca from Piano Sonata in A Major, K. 331 (Mozart) Canon (Pachelbel) *** Rondeau from Incidental Music to Abdelazer (Purcell) When I Am Laid in Earth from Dido and Aeneas (Purcell) Trumpet Tune (Purcell) *** Scheherazade Theme (Rimsky-Korsakov) Andante from String Quartet in A minor, Op. 29 (Schubert) "Rosamunde" (Schubert) Traumerei from Kinderscenen, Op. 15, #7 (Schumann) Simple Gifts (Shaker Hymn) Presto from Sonatina in F Major (Telemann) Vivace from Sonata in F Major for flute (Telemann) Be Thou My Vision (Traditional Irish Melody) Danza Pastorale from Violin Concerto in E Major, Op. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music