A Study of Gian Carlo Menotti's Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

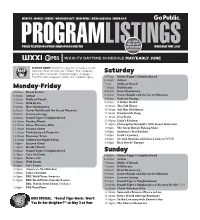

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

Choose Yourfavorite Three Concerts

CHOOSE YOUR FAVORITE THREE CONCERTS. You’ll Save 33% – That’s Up to $200 in Savings with Added Benefits Call 212-875-5656 or visit nyphil.org/CYO33 and use promo code CYO33. ** U.S. Premiere–New York Philharmonic Co-Commission with the London Philharmonic Orchestra *** World Premiere–New York Philharmonic Commission † Commissions made possible by The Marie-Josée Kravis Prize for New Music †New York City Premiere–New York Philharmonic Co-Commission Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 7:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 8:00pm 8:00pm unless otherwise noted unless otherwise noted Conductor Guest Artists Program Esa-Pekka Leila Josefowicz violin RAVEL Mother Goose Suite NOV Salonen Esa-Pekka SALONEN Violin Concerto NOV OCT OCT NOV conductor (New York Concert Premiere) 5 30 31 1 2 SIBELIUS Symphony No. 5 (11:00am) Bernard Miah Persson soprano J.S. BACH Cantata No. 51, Jauchzet Labadie Stephanie Blythe Gott in allen Landen! conductor mezzo-soprano HANDEL “Let the Bright Seraphim” Frédéric Antoun tenor from Samson Andrew Foster- MOZART Requiem NOV NOV NOV Williams bass 7 8 9 Matthew Muckey trumpet New York Choral Artists Joseph Flummerfelt director Alan Gilbert Liang Wang oboe R. STRAUSS Also sprach Zarathustra conductor Glenn Dicterow, violin NOV Christopher ROUSE Oboe Concerto NOV NOV NOV 15 (New York Premiere) 19 14 16 R. STRAUSS Don Juan (2:00pm) Glenn Dicterow, violin Alan Gilbert Paul Appleby tenor BRITTEN Serenade for Tenor, Horn, conductor Philip Myers horn and Strings Kate Royal soprano BRITTEN Spring Symphony Sasha Cooke mezzo-soprano NOV NOV NOV New York Choral Artists 21 22 23 Joseph Flummerfelt director Brooklyn Youth Chorus Dianne Berkun- Menaker director Alan Gilbert Paul Appleby tenor MOZART Symphony No. -

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

Msm Camerata Nova

Saturday, March 6, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM CAMERATA NOVA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM JAMES LEE III A Narrow Pathway Traveled from Night Visions of Kippur (b. 1975) CHARLES WUORINEN New York Notes (1938–2020) (Fast) (Slow) HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS Chôros No. 7 (1887–1959) MAURICE RAVEL Introduction et Allegro (1875–1937) CAMERATA NOVA VIOLIN 1 VIOLA OBOE SAXOPHONE HARP Youjin Choi Sara Dudley Aaron Zhongyang Ling Minyoung Kwon New York, New York New York, New York Haettenschwiller Beijing, China Seoul, South Korea Baltimore, Maryland VIOLIN 2 CELLO PERCUSSION PIANO Ally Cho Rei Otake CLARINET Arthur Seth Schultheis Melbourne, Australia Tokyo, Japan Ki-Deok Park Dhuique-Mayer Baltimore, Maryland Chicago, Illinois Champigny-Sur-Marne, France FLUTE Tarun Bellur Marcos Ruiz BASSOON Plano, Texas Miami, Florida Matthew Pauls Simi Valley, California ABOUT THE ARTISTS George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Prospero's Rooms

2020 FEB HADELICH PLAYS PAGANINI 2019-20 HAL & JEANETTE SEGERSTROM FAMILY FOUNDATION CLASSICAL SERIES Michael Francis, conductor Rouse PROSPERO’S ROOMS Augustin Hadelich, violin Paganini VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 IN D MAJOR Allegro maestoso Adagio Rondo: Allegro spiritoso Augustin Hadelich Intermission Rachmaninoff SYMPHONY NO. 3 IN A MINOR Lento—Allegro moderato—Allegro Adagio ma non troppo—Allegro Allegro—Allegro vivace Thursday, February 27, 2020 @ 8 p.m. Friday, February 28, 2020 @ 8 p.m. The appearances of Augustin Hadelich and Saturday, February 29, 2020 @ 8 p.m. Michael Francis have been generously underwritten by Segerstrom Center for the Arts a gift from Sam and Lyndie Ersan. Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall OFFICIAL MEDIA SPONSOR This concert is being recorded for broadcast on Sunday, March 15, 2020, on Classical KUSC. PacificSymphony.org FEB 2020 5 PROGRAM NOTES in the world of atonality; yet he was also a influenced his compositional as well as rock’n’roll fan (Led Zeppelin was a favorite) his playing style. and taught a class on the history of rock None of this even begins to suggest Christopher Rouse: while on the faculty at the Eastman School the nature or extent of Paganini’s of Music. celebrity, which spread through Italy Prospero’s Rooms Regarding Prospero’s Rooms, Rouse and then took Europe by storm. After an Lovers of classical noted on his website: “In the days when I 1813 concert at Milan’s La Scala opera music lost one would have still contemplated composing house, he was spoken of in the same of their own in an opera, my preferred source was Edgar reverential tones as other great violinists, 2019 when the Allan Poe’s ‘Masque of the Red Death.’… including Charles Philippe Lafont and Pulitzer Prize- However… I decided to redirect my ideas Louis Spohr. -

THE BALDWIN PIANO COMPANY * Singing Boys of Norway Springfield (Mo.) Civic Symphony Orchestra St

Music Trade Review -- © mbsi.org, arcade-museum.com -- digitized with support from namm.org Each artist has his own reason for choosing Baldwin as the piano which most nearly approaches the ever-elusive goal of perfection. As new names appear on the musical horizon, an ever-increasing number of them are joining their distinguished colleagues in their use of the Baldwin. Kurt Adler Cloe Elmo Robert Lawrence Joseph Rosenstock Albuquerque Civic Symphony Orchestra Victor Alessandro Daniel Ericourt Theodore Lettvin Aaron Rosand Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Ernest Ansermet Arthur Fiedler Ray Lev Manuel Rosenthal Baton Rouge Symphony Orchestra Claudio Arrau Kirsten Flagstad Rosina Lhevinne Jesus Maria Sanroma Beaumont Symphony Orchestra Wilhelm Bachaus Lukas Foss Arthur Bennett Lipkin Maxim Schapiro Berkshire Music Center and Festival Vladimir Bakaleinikoff Pierre Fournier Joan Lloyd George Schick Birmingham Civic Symphony Stefan Bardas Zino Francescatti Luboshutz and Nemenoff Hans Schwieger Boston "Pops" Orchestra Joseph Battista Samson Francois Ruby Mercer Rafael Sebastia Boston Symphony Orchestra Sir Thomas Beecham Walter Gieseking Oian Marsh Leonard Seeber Brevard Music Foundation Patricia Benkman Boris Goldovsky Nino Martini Harry Shub Burbank Symphony Orchestra Erna Berger Robert Goldsand Edwin McArthur Leo Sirota Central Florida Symphony Orchestra Mervin Berger Eugene Goossens Josefina Megret Leonard Shure Chicago Symphony Orchestra Ralph Berkowitz William Haaker Darius Milhaud David Smith Pierre Bernac Cincinnati May Festival Theodor Haig -

THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27Th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director

THEOOOPER~ONFORUM November 14, 1980, Spm THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director MEET THE MODERNS 1: MUSIC + DRAMA two one-act operas THE CRY OF CLYTAEMNESTRA THE EGG Music by John Eaton an operatic riddle Libretto by Patrick Creagh Music and Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti New York premiere New York premiere RICHARD DUNCAN, conductor LUKAS FOSS, conductor Staging by Maurice Edwards Staging by Maurice Edwards Lighting by William Mintzer Lighting by William Mintzer Sound Co-ordinator: Lonnie Juli Costumes by Constance Mellen Cast Cast (in o rder of appearance) (in o rder of appearance) ClytaernJlt'~tra Quec•11 o{ Ar,J~e>S . elcla elson Manuel ................................... Martin Strother lphygene1a eldest dau,J~hter o{ C/ytaemnestra St Simeon Stylites .............................joseph Levitt !111(/ A.I!Cllll£'11111011 . • • • . • . • Sally Wolf BasJIJssa Empress o{ ByzantiUm ( Pnde} . ............ Edith Diggory Agamemnon KJII,JI of ArJioS . • . • • . Tim o ble Areobindus. {avonte o{the Bas111ssa (Lust} .......... Steven Nelson Ody~seus . Ri chard Walker Gourmantus, the cook (Gluttony} . ....... ........ Ted Adkins Menelaus . ·- . Brian Trego Eunuch of the Sacred Cubicle !Slot hi ............ Richard Walker DJOilll'tks . Martin Strother Pachomius. the treasurer (A vance} . .................. Jon Fay TnKer . Steven Nelson Sister of the BasJIJssa !Envyl . ...... ............... Paula Redd Calcha~. HlJih Pnest. joseph Levitt Julian, Capt am o{ the Guard (Anger} (silent role} . .. ..... Brian Trego Acl11llcs . .Jon Fay Beggar Woman . ... .............. Sarah Miller Electra. dauxhter o{ C/ytaem11estra and !Chorusl ............ Axamemncm. as a ch1ld . ................. .. ....... Abby Tate Members of the Basi IIssa's Court Sally Wolf, Martha Waltman Rebecca Field, Glenn Siebert, Colenton Freeman Orestes. so11 o{ Clytaem>lestra and Agamemnon, as a child . -

2011 Tanglewood Season Listing All Programs and Artists Are Subject to Change

2011 Tanglewood Season Listing All programs and artists are subject to change. Saturday, June 25, at 7 p.m. Koussevitzky Music Shed Earth, Wind, and Fire Tuesday, June 28, 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. Theatre Wednesday, June 29, 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. Theatre String Quartet Marathon Two 2‐hour concerts each day Tuesday, June 28, 8 p.m. Ozawa Hall Wednesday, June 29, 8 p.m. Ozawa Hall Mark Morris Dance Group Tanglewood Music Center Fellows Mark Morris, choreographer Yo‐Yo Ma, cello Isaac Mizrahi, costume designer Phil Sandstrom and Michael Chybowski, lighting designers Frisson Stravinsky ‐ Symphonies of Wind Instruments New work (world premiere; BSO commission) Stravinsky ‐ Renard Falling Down Stairs J.S. Bach ‐ Suite No. 3 in C for solo cello, BWV 1009 Thursday, June 30, 8 p.m. Ozawa Hall James Taylor in Ozawa Hall James Taylor and guests In the more intimate setting of Tanglewood's Ozawa Hall, James Taylor offers the music that has made him one of the most beloved artists of our day. Friday, July 1, 8:30 p.m. Shed James Taylor and the Boston Pops Boston Pops James Taylor, soloist John Williams, conductor Tanglewood’s favorite singer joins “America's Orchestra,” the Boston Pops and John Williams for a remarkable collaboration. Saturday, July 2, 5:45 p.m. Shed A Prairie Home Companion at Tanglewood with Garrison Keillor Live broadcast Sunday, July 3, 7 p.m. Shed Monday, July 4, 7 p.m. Shed The Essential James Taylor James Taylor returns to Tanglewood with his extraordinary band of musicians for two spectacular performances. -

April 2008 in This Issue

The Sacred in Opera April 2008 In this Issue... Ruth Dobson For the next two editions of the SIO newsletter, we are taking an in-depth look at one-act Christmas operas which can be easily produced and are appropriate for both children and adults. This issue we will profile Amahl and the Night Visitors, Only a Miracle, St. Nicholas, Good King Wenceslas, and The Shepherd’s Play. The next issue will highlight The Christmas Rose, The Greenfield Christmas Tree, The Finding of the King, The Night of the Star, and others. Thanks to Allen Henderson for sharing his insight into a triology of operas by Richard Shephard, Good King Wenceslas, The Shepherd’s Play, and St. Nicholas, with us in this issue. As great as Amahl and the Night Visitors is, there are these and other works waiting to be discovered by all of us. We hope you will find these suggestions interesting. These operas vary in length from 10 minutes to an hour, and can be presented alone or paired with others. Amahl and the Night Visitors is almost always a successful box office draw. Pairing it with a lesser known work could make for a very enjoyable afternoon or evening presentation and give audiences an opportunity to enjoy other equally wonderful works. Several of these operas use children as cast members, while others call for only adult performers, but all have stories appropriate for children. They are written in a variety of styles and have very different production requirements. Producers would need to take into consideration the ages of the children that are the target audience. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Pacific 231 (Symphonic Movement No

Pacific 231 (Symphonic Movement No. 1) Arthur Honegger (1892–1955) Written: 1923 Movements: One Style: Contemporary Duration: Six minutes As a young man trying to figure his way in the world of music, Miklós Rózsa (a Hollywood film composer) asked the French composer Arthur Honegger “How are we composers expected to make a living?” “Film music,” he said. “What?” I asked incredulously. I was unable to believe that Arthur Honegger, the composer of King David, Judith and other great symphonic frescos, of symphonic poems and chamber music, could write music for films. I was thinking of the musicals I had seen in Germany and of films like The Blue Angel, so I asked him if he meant foxtrots and popular songs. He laughed again. “Nothing like that,” he said, ‘I write serious music.’ As a young man, Honegger was part of a group of renegade composers in Paris grouped around the avant-garde poet Jean Cocteau called “Les Six.” Unlike, the other composers in “Les Six,” Honegger’s music is weightier and less flippant. In the 1920s, Honegger worked on three short orchestral pieces that he called Mouvements symphonique. In his autobiography, I am a Composer, he recounts his intent with the first: To tell the truth, In Pacific I was on the trail of a very abstract and quite ideal concept, by giving the impression of a mathematical acceleration of rhythm, while the movement itself slowed. It was only after he wrote the work that he gave it the title. “A rather romantic idea crossed my mind, and when the work was finished, I wrote the title, Pacific 231, which indicates a locomotive for heavy loads and high speed.” Given a title, people heard things that weren’t there.