Considerations for Producing Media for Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Clash of Two Images China's Media

THE CLASH OF TWO IMAGES CHINA’S MEDIA OFFENSIVE IN THE UNITED STATES by FAN BU MAY 2013 Committee Fritz Cropp, Chair Clyde Bentley Wesley Pippert ii THE CLASH OF TWO IMAGES CHINA’S MEDIA OFFENSIVE IN THE UNITED STATES Fan Bu Fritz Cropp, Project Supervisor ABSTRACT At a time when most Western newspaper and broadcasting companies are scaling back, China's state-run media organizations are fast growing and reaching into every corner of the world, especially in North America and Africa. The $7 billion campaign to expand China’s soft power has significantly increased its media presence. But are these media offensive efforts effective? This paper analyzes the current state of the media expansion, the motivation behind it, the obstacles, suggestions and the outlook in the decades to come. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………...……………………….ii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................1 Goals of the Study 2. WEEKLY FIELD NOTES………………………………………………………..4 3. EVALUATION…………………………………………………………………..35 4. PHYSICAL EVIDENCE OF WORK……………………………………………39 5. ANALYSIS COMPONENT……………………………………………………..42 REFERENCES…………………………………………………………………………..53 APPENDIX 1. PROFESSIONAL PROJECT PROPOSAL………………………...……………55 2. QUERY LETTER..................................................................................................66 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Growing up in Beijing, I was one of hundreds of millions who watched the China Central TV prime time newscast each night at 7. But I never realized how biased the programs were until I traveled back home recently after studying and working in journalism in the United States for five years. In the half-hour show, international news normally takes 5 to 10 minutes, most of which report on negative news around the world, such as riots in the Middle East or the economic crisis in Europe. -

Morrison Announces Resignation As A.D. Fire Marshall Confident About

Dmlv Nexus Volume 69, No. 105 Wednesday, April 5, 1989_______________________ University of California, Santa Barbara One Section, 16 Pages Devereaux Morrison Announces Operating Resignation as A.D. had with players.... To have a License in San Jose State Head chance at this stage of my life to go back to that is something I Coaching Offer Too can’t say no to. I’ve had some opportunities before this, but this Jeopardy Good to Let Pass By, one made sense.” Immediate impacts from Signs Four-Year Deal Morrison’s decision include questions regarding morale I.V. School Tightens within the Gaucho sports circle, By Scott Lawrence especially by coaches who say Security Procedures Staff Writer Morrison had made great strides in terms of personnel fervor and White Investigations UCSB Athletic Director Stan sense of purpose. Morrison resigned Tuesday to Reaction to Morrison’s an by State Continues accept the head basketball nouncement was consistent coaching position at San Jose among the coaches, who stood State, he announced at a Tuesday stunned inside the Events Cen morning press conference. ter’s Founder’s Room while By Adam M oss Morrison, a former head coach Morrison gave a 45-minute ad Staff Writer at Pacific and USC, will replace dress on his decision and on the Bill Berry, who was fired last state of Gaucho athletics. Under the looming threat of month following a season under “I’ve been here 13 years,” losing its license, the Devereux fire that began when 10 Spartan Head Women’s Volleyball Coach School in Isla Vista volunteered to players walked off the squad on Kathy Gregory said, “and I’d like increase security and tighten its Jan. -

Festival Daily

tuesday 2. 7. 2019 05 free festival kviff’s main media partner Inside Main Competition: The Father and Half-Sister 02 daily Road trip Over the Hills 03 East of the West: tense connections 04 special edition of Právo Photo: KVIFF Photo: According to the film’s director, Hutchence had a way to cut through Melbourne punk scene bullshit. Beyond the rock star Lowenstein says in making the fi lm he gained some insight into his old friend’s character because he would show one side of himself Trapped in the 80s to his male friends that relied on having a good time, his more pub- lic persona. “He would always give Mystify: Michael Hutchence reveals the complicated fi gure behind the you a taste of what it was like to be a rock star,” he says. “But you never mythical INXS frontman really sat down and had big discus- sions about himself.” The film offered another, more In his documentary on the magnetic, enigmatic and ultimately tragic frontman for 80 s megastars INXS, Michael intimate view of the singer by the Hutchence, director Richard Lowenstein – who arrived in Karlovy Vary for the fi lm’s European premiere – plunges degree to which the perspective on him is female - with deeply the viewer completely into the singer’s life and times by only using footage from the past, without relying on talking revealing interviews from mostly heads. ex-girlfriends such as Michele Bennett, Kylie Minogue and Helena Christensen, as well as by Michael Stein personal footage of Hutchence? likes of Nick Cave and Th e Birthday out to a beach in Queensland and their US tour manager Martha It turns out he just had to walk Party had emerged, another uni- was immediately disarmed by the Troup. -

Youtube Strategies 2015 How to Make and Market Youtube Videos

Disclaimer I create commercial content that pays bills. I am, what many would call, an information marketer. Often, I am the provider (and/or business owner) of the products and/or services that I recommend. Being in this business provides me with such a wonderful opportunity; it’s part of how I pay those bills. Occasionally, I am compensated by the products and services I recommend. It is sometimes direct; it is sometimes indirect; but it is there. If this offends you, no problem; this isn’t content for you. Return this book. We can still be friends. At all times, I only recommend products I use – or would tell my Mom to use. You have my promise there. About The Author Paul Colligan helps others leverage technology to expand their reach (and revenue) with reduced stress and no drama. He does this with a lifestyle and business designed to answer the challenges and opportunities of today’s ever- changing information economy. If you are looking for titles, he is a husband, father, 7-time bestselling author, podcaster, keynote speaker and CEO of Colligan.com. He lives in Portland, Oregon with his wife and daughters and enjoys theater, music, great food and travel. Paul believes in building systems and products that work for the user – not vice versa. With that focus, he has played a key role in the launch of dozens of successful web and internet products that have garnered tens of millions of visitors in traffic and dollars in revenue. Previous projects have included work with The Pulse Network, Traffic Geyser, Rubicon International, Piranha Marketing, Microsoft and Pearson Education. -

Music Games Rock: Rhythm Gaming's Greatest Hits of All Time

“Cementing gaming’s role in music’s evolution, Steinberg has done pop culture a laudable service.” – Nick Catucci, Rolling Stone RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME By SCOTT STEINBERG Author of Get Rich Playing Games Feat. Martin Mathers and Nadia Oxford Foreword By ALEX RIGOPULOS Co-Creator, Guitar Hero and Rock Band Praise for Music Games Rock “Hits all the right notes—and some you don’t expect. A great account of the music game story so far!” – Mike Snider, Entertainment Reporter, USA Today “An exhaustive compendia. Chocked full of fascinating detail...” – Alex Pham, Technology Reporter, Los Angeles Times “It’ll make you want to celebrate by trashing a gaming unit the way Pete Townshend destroys a guitar.” –Jason Pettigrew, Editor-in-Chief, ALTERNATIVE PRESS “I’ve never seen such a well-collected reference... it serves an important role in letting readers consider all sides of the music and rhythm game debate.” –Masaya Matsuura, Creator, PaRappa the Rapper “A must read for the game-obsessed...” –Jermaine Hall, Editor-in-Chief, VIBE MUSIC GAMES ROCK RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME SCOTT STEINBERG DEDICATION MUSIC GAMES ROCK: RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME All Rights Reserved © 2011 by Scott Steinberg “Behind the Music: The Making of Sex ‘N Drugs ‘N Rock ‘N Roll” © 2009 Jon Hare No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Thesis Writing Deliverables (Pdf)

DEFENSE SPEECH Discovering and listening to music has always been my biggest passion in life and my primary way of coping with my emotions. I think its main appeal to me since childhood has been the comfort it brings in knowing that at some point in time, another human felt the same thing as me and was able to survive and express it by making something beautiful. For my project, I recorded a 9 track album called Strange Machines while I was on leave of absence last year. This term, I created a 20 minute extended music video to accompany it. All of this lives on a page I coded on my personal website with some fun bonus content that I’ll scroll through at the end of this presentation. I’ll put the link in the comments so anyone who’s interested can check it out at their own pace. I have so much fun making music and feel proud when I have a cohesive finished product at the end. I’m not interested in becoming a virtuoso musician or a professional producer. A lot of trained musicians gatekeep, intimidate, and discourage amateurs. People mystify and mythologize the creative process as if it’s the product of some elusive, innate genius rather than practice, experimentation, and a simple love of music. As someone who’s work exists entirely as digital recordings, there’s no inherent reason for me to be an amazing guitar player who can play a song perfectly all the way through, as mistakes can be easily cut out and re-recorded. -

Sega Mega CD

Sega Mega CD Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Eye of the Beholder Sega Adventures of Batman & Robin, The Sega After Burner III Sega Amazing Spider-Man vs. The Kingpin, The Sega Animals, The Mindscape Batman Returns Sega Battlecorps Core Design Battlecorps: Sega Pro Demo Core Design Battlecorps: Mega Power Demo Mega Power BC Racers Core Design BC Racers Demo: Sega Pro Demo Sega Pro BC Racers Demo: Mega Power Demo Mega Power Beast II Sony Imagesoft Blackhole Assault Sega Bloodshot Acclaim Brutal: Paws of Fury Gametek Bug Blasters: The Exterminators Good Deal Games Chuck Rock Sony Imagesoft Chuck Rock II: Son of Chuck Core Design Corpse Killer Digital Pictures Double Switch Sega Dracula Unleashed Sega Dragon's Lair Sega Dune Virgin Dungeon Explorer Hudson Soft Dungeon Master II: Skullkeep JVC Earthworm Jim: Special Edition Interplay Ecco the Dolphin Sega Ecco the Dolphin: Black Label Sega Ecco: The Tides of Time Sega ESPN Baseball Tonight Sony Imagesoft Eternal Champions: Challenge from the Dark Side Sega Fahrenheit Sega Fatal Fury Special JVC Fatal Fury Special: Demo JVC / Sega Pro FIFA International Soccer: Championship Edition Electronic Arts FIFA International Soccer: Championship Edition: Mega Power Demo Mega Power FIFA International Soccer: Championship Edition: Sega Pro Demo Sega Pro Final Fight CD Sega Flashback: Demo Sega Pro Flux Virgin Interactive Formula One World Championship: Beyond the Limit Sega Ground Zero Texas Sony Imagesoft Hook Sony Imagesoft Jaguar XJ220 Sega Jurassic Park Sega Keio Flying Squadron JVC Keio Flying Squadron: Demo JVC Kids on the Site Digital Pictures Lawnmower Man, The Time Warner Lawnmower Man, The: Demo Mega Power Lethal Enforcers Konami Lethal Enforcers II: Gun Fighters Konami Lethal Enforcers II: Gunfighters: Demo Mega Power This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

ART CRITICISM I I, I

---~ - --------c---~ , :·f' , VOL. 14, No.2 ART CRITICISM i I, I ,\ Art Criticism vol. 14, no. 2 Art Department State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, NY 11794-5400 The editor wishes to thank Jamali and Art and Peace, Inc., The Stony . Brook Foundation, President Shirley Strumm Kenny, Provost Rollin C. Richmond, the Dean ofHumaniti~s and Fine Arts, Paul Armstrong, for their gracious support. Copyright 1999 State University of New York at Stony Brook ISSN: 0195-4148 2 Art Criticism Table of Contents Abstract Painting in the '90s 4 Mary Lou Cohalan and William V. Ganis Figurative Painting in the '90s 21 Jason Godeke, Nathan Japel, Sandra Skurvidaite Pitching Charrettes: Architectural Experimentation in the '90s 34 Brian Winkenweder From Corporeal Bodies to Mechanical Machines: 53 Navigating the Spectacle of American Installation in the '90s Lynn Somers with Bluewater Avery and Jason Paradis Video Art in the '90s 74 Katherine Carl, Stewart Kendall, and Kirsten Swenson Trends in Computer and Technological Art 94 Kristen Brown and Nina Salvatore This issue ofArt Criticism presents an overview ofart practice in the 1990s and results from a special seminar taught by Donald B. Kuspit in the fall of 1997. The contributors are current and former graduate students in the Art History and Criticism and Studio Art programs at Stony Brook. vol. 14, no. 2 3 Abstract Painting in the '90s by Mary Lou Cohalan and William V. Ganis Introduction In a postmodem era characterized by diversity and spectacle, abstract painting is just one of many fonnal strategies in the visual art world. -

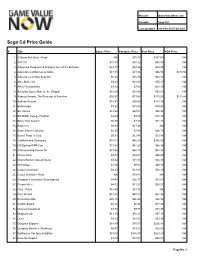

Sega Cd Price Guide

Website GameValueNow.com Console Sega Cd Last Updated 2018-09-30 07:06:24.0 Sega Cd Price Guide # Title Loose Price Complete Price New Price VGA Price 1. 3 Ninjas Kick Back / Hook NA $75.08 $127.61 NA 2. A/X-101 $31.83 $34.32 $84.88 NA 3. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Eye of the Beholder $10.17 $23.26 $33.95 NA 4. Adventures of Batman & Robin $17.51 $31.72 $96.55 $119.50 5. Adventures of Willy Beamish $6.20 $15.73 $51.86 NA 6. After Burner III $5.21 $18.56 $55.07 NA 7. AH-3 Thunderstrike $3.34 $7.66 $28.25 NA 8. Amazing Spider-Man vs. the Kingpin $16.08 $31.88 $99.51 NA 9. Android Assault: The Revenge of Bari-Arm $36.67 $73.64 $175.50 $112.84 10. Batman Returns $14.81 $20.68 $101.16 NA 11. Battlecorps $3.70 $15.50 $39.41 NA 12. BC Racers $13.56 $63.71 $96.92 NA 13. Bill Walsh College Football $2.49 $5.65 $12.98 NA 14. Black Hole Assault $5.35 $7.49 $74.11 NA 15. Bouncers $6.83 $17.49 NA NA 16. Bram Stoker's Dracula $4.25 $7.99 $26.73 NA 17. Brutal: Paws of Fury $5.93 $12.41 $33.98 NA 18. Cadillacs and Dinosaurs $14.72 $46.69 $156.50 NA 19. CD Backup RAM Cart $37.04 $47.28 $65.98 NA 20. Championship Soccer 94 $33.86 $68.25 $82.80 NA 21. -

An Interview with Nelson Henricks

Mike Hoolboom Ironic Nostalgia: an Interview with Nelson Henricks Source: Practical Dreamers: Conversations with Movie Artists, Mike Hoolboom, 2007 MH: Artists often play with the means of systems other than Hollywood cinema and ent than ever, how is fringe media working expression, the way a message or story is network television, and refer to a broader to enter the breaches of representation? told. For the uninitiated, this often makes the spectrum of human activities than can usu- work bewildering and confusing. Why is it ally be contained within conventional forms. NH: Well, I don’t think fringe work is politi- necessary to alter the shaping of pictures? cally efficacious. Most of it was never meant When I was in a band we started doing to be. Someone said (I forget who) that NH: If I understand the question correctly, cover versions but soon realized that it was politics should not be used as a measure of I believe you are asking why artist’s work easier to make original material. I remember the worth of something. Bad art can have looks so much different that what we see the singer saying, “It’s easier to write and good political effects, but does that make in mainstream media. My initial response play our own songs because no one can it better art? was going to be that artist’s work is part tell when you make a mistake.” You imme- of a larger constellation of alternative uses diately abandon questions of technique Deleuze and Guattari wrote about rhizom- of film and video media, so it isn’t all that (”Can I play this perfectly?”), and move atic structures as a way of combating fas- extraordinary. -

Press Release 28/5/2019

Organizer of the 54th Karlovy Vary IFF 2019: Film Servis Festival Karlovy Vary, a.s. Organizers of the 54th Karlovy Vary IFF thank to all partners which help to organize the festival. 54th Karlovy Vary IFF is supported by: Ministry of Culture Czech Republic Main partners: Vodafone Czech Republic a.s. innogy MALL.CZ Accolade City of Karlovy Vary Karlovy Vary Region Partners: UniCredit Bank Czech Republic and Slovakia, a.s. UNIPETROL SAZKA Group the Europe’s largest lottery company DHL Express (Czech Republic), s.r.o. Philip Morris ČR, a.s. CZECH FUND – Czech investment funds Official car: BMW Official fashion partner: Pietro Filipi Official coffee: Nespresso Supported by: CZ - Česká zbrojovka a.s. Supported by: construction group EUROVIA CS Supported by: CZECHOSLOVAK GROUP Partner of the People Next Door section: Sirius Foundation Official non-profit partner: Patron dětí Film Servis Festival Karlovy Vary, Panská 1, 110 00 Praha 1, Czech Republic Tel. +420 221 411 011, 221 411 022 www.kviff.com In cooperation with: CzechTourism, Ministry of Regional Development Official beverage: Karlovarská Korunní Official beauty partner: Dermacol Official champagne: Moët & Chandon Official beer: Pilsner Urquell Official drink: Becherovka Main media partners: Czech Television Czech Radio Radiožurnál PRÁVO Novinky.cz REFLEX Media partners: BigBoard Praha PLC ELLE Magazine magazine TV Star Festival awards supplier: Moser Glassworks Software solutions: Microsoft Partner of the festival Instagram: PROFIMED Main hotel partners: SPA HOTEL THERMAL Grandhotel Pupp Four Seasons Hotel Prague Partner of the No Barriers Project: innogy Energie Wine supplier: Víno Marcinčák Mikulov - organic winery GPS technology supplier: ECS Invention spol. -

NA EU Art Alive! Western Technologies •Segana/EU/JP Buck

688 Attack Sub Electronic Arts Sega NA EU NA EU Art Alive! Western Technologies •SegaNA/EU/JP NAJP BREU Buck Rogers: Countdown to Doomsday Strategic Simulations •Electronic ArtsNA/EU NABR EU California Games •EpyxOriginal design •SegaNA/EU BR Centurion: Defender of Rome •Bits of Magic Electronic Arts NA EU Divine Sealing (Unlicensed) Studio Fazzy CYX JP Hardball! Accolade Ballistic NA EU NA EU James Pond: Underwater Agent •Millennium Interactive •Electronic ArtsNA/EU BR John Madden Football '92 Electronic Arts EASN NA EU M-1 Abrams Battle Tank Dynamix Electronic Arts/Sega NA EU NA EU Marble Madness Atari Electronic Arts JP Mario Lemieux Hockey Ringler Studios Sega NA EU NA EU Marvel Land Namco Namco JP Master of Monsters Systemsoft Renovation Products NA JP Master of Weapon Taito Taito JP NA EU Mercs Capcom Capcom JP Mickey's Ultimate Challenge Designer Software Hi Tech Expressions NA Might and Magic: Gates to Another World New World Computing Electronic Arts NA EU Mike Ditka Power Football Ballistic Accolade NA Ms. Pac-Man General Computer Corp. Tengen NA EU NA EU Mystical Fighter Taito DreamWorks JP Onslaught •RealmsOriginal Design Ballistic NA NA JP Rampart •Atari GamesOriginal design •TengenNA/JP KR Rings of Power Naughty Dog Software Electronic Arts NA EU NA EU Road Rash Electronic Arts •Electronic ArtsNA/EU JP BR Saint Sword Taito Taito NA JP NA EU Shadow of the Beast Psygnosis Electronic Arts NAJP EU Space Invaders '91 Taito Taito NAJP EU Speedball 2 The Bitmap Brothers Arena Entertainment JP NA EU Spider-Man Sega Sega JP Starflight