High-Speed Rail: a National Perspective High-Speed Rail Experience in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harrisburg Line Capacity Improvements Upgrade of Track 2 from Glen Interlocking to Thorn Interlocking

HARRISBURG LINE CAPACITY IMPROVEMENTS UPGRADE OF TRACK 2 FROM GLEN INTERLOCKING TO THORN INTERLOCKING FEDERAL RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION FEDERAL-STATE PARTNERSHIP FOR STATE OF GOOD REPAIR PROGRAM GRANT APPLICATION Lead Applicant: Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) Joint Applicant: Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) FEDERAL FUNDING REQUESTED: $8,337,500 (50%) PROPOSED NON-FEDERAL MATCH: $8,337,500 (50%) TOTAL PROJECT COST: $16,675,000 PROJECT LOCATION: Caln Township, Downingtown Borough, East Caln Township, West Whiteland Township, & East Whiteland Township in Chester County, Pennsylvania - 6th Congressional District No Federal Grant Application Previously Submitted for this Project Table of Contents I. Project Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Project Funding ..................................................................................................................................... 2 III. Applicant Eligibility ............................................................................................................................... 3 IV. NEC Project Eligibility ........................................................................................................................... 3 V. Detailed Project Description ................................................................................................................ 5 VI. Project Location ................................................................................................................................. -

NORTHEAST CORRIDOR New York - Washington, DC

NORTHEAST CORRIDOR New York - Washington, DC September 5, 2017 NEW YORK and WASHINGTON, DC NEW YORK - NEWARK - TRENTON PHILADELPHIA - WILMINGTON BALTIMORE - WASHINGTON, DC and intermediate stations Acela Express,® Reserved Northeast RegionalSM and Keystone Service® THIS TIMETABLE SHOWS ALL AMTRAK SERVICE FROM BOSTON OR SPRINGFIELD TO POINTS NEW YORK THROUGH WASHINGTON, DC. Also see Timetable Form W04 for complete Boston/Springfield to Washington, DC schedules, and Timetable Form W06 for service to Virginia locations. FALL HOLIDAYS Special Thanksgiving timetables for the period, November 20 through 27, 2017, will appear on Amtrak.com shortly and temporarily supersede these schedules. 1-800-USA-RAIL Amtrak.com Amtrak is a registered service mark of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Washington Union Station, 60 Massachusetts Ave. N.E., Washington, DC 20002. NRPC Form W2–Internet only–9/5/17. Schedules subject to change without notice. Depart Depart Depart Depart Depart Arrive Depart Depart Depart Depart Depart Arrive Train Name/Number Frequency New York Newark Newark Intl. Air. Metropark Trenton Philadelphia Philadelphia Wilmington Baltimore BWI New Carrollton Washington Northeast Regional 67 Mo-Fr 3 25A 3 45A —— 4 00A 4 25A 4 52A 5 00A 5 22A 6 10A 6 25A 6 40A 7 00A Northeast Regional 151 Mo-Fr 4 40A R4 57A —— 5 12A 5 35A 6 04A 6 07A 6 28A 7 27A 7 40A D7 59A 8 14A Northeast Regional 111 Mo-Fr 5 30A R5 46A —— 6 00A 6 26A 6 53A 6 55A 7 15A 8 00A 8 15A D8 29A 8 50A Acela Express 2103 Mo-Fr -

Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States

Parsons Brinckerhoff 2010 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Monograph 26 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States Fellow: Francis P. Banko Professional Associate Principal Project Manager Lead Investigator: Jackson H. Xue Rail Vehicle Engineer December 2012 136763_Cover.indd 1 3/22/13 7:38 AM 136763_Cover.indd 1 3/22/13 7:38 AM Parsons Brinckerhoff 2010 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Monograph 26 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States Fellow: Francis P. Banko Professional Associate Principal Project Manager Lead Investigator: Jackson H. Xue Rail Vehicle Engineer December 2012 First Printing 2013 Copyright © 2013, Parsons Brinckerhoff Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, mechanical (including photocopying), recording, taping, or information or retrieval systems—without permission of the pub- lisher. Published by: Parsons Brinckerhoff Group Inc. One Penn Plaza New York, New York 10119 Graphics Database: V212 CONTENTS FOREWORD XV PREFACE XVII PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE RESEARCH 3 1.1 Unprecedented Support for High Speed Rail in the U.S. ....................3 1.2 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the U.S. .....4 1.3 Research Objectives . 6 1.4 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Participants ...........................6 1.5 Host Manufacturers and Operators......................................7 1.6 A Snapshot in Time .................................................10 CHAPTER 2 HOST MANUFACTURERS AND OPERATORS, THEIR PRODUCTS AND SERVICES 11 2.1 Overview . 11 2.2 Introduction to Host HSR Manufacturers . 11 2.3 Introduction to Host HSR Operators and Regulatory Agencies . -

PRIIA Report

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2020 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2020) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2020 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning Urban and Regional Planning January 2007 High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2 Allison deCerreno Shishir Mathur San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/urban_plan_pub Part of the Infrastructure Commons, Public Economics Commons, Public Policy Commons, Real Estate Commons, Transportation Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Allison deCerreno and Shishir Mathur. "High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2" Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning (2007). This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban and Regional Planning at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MTI Report 06-03 MTI HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS-PART 2 IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS-PART HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: Funded by U.S. Department of HIGH-SPEED RAIL Transportation and California Department PROJECTS IN THE UNITED of Transportation STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS PART 2 Report 06-03 Mineta Transportation November Institute Created by 2006 Congress in 1991 MTI REPORT 06-03 HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS PART 2 November 2006 Allison L. -

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi M.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2011 B.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2009 Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2016 © 2016 Tatsuya Doi. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________________ Institute for Data, Systems, and Society May 6, 2016 Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Joseph M. Sussman JR East Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Olivier L. de Weck Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: _________________________________________________________________________ John N. Tsitsiklis Clarence J. Lebel Professor of Electrical Engineering IDSS Graduate Officer 1 2 Interaction of Lifecycle Properties In High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society on May 6, 2016 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems ABSTRACT High-Speed Rail (HSR) has been expanding throughout the world, providing various nations with alternative solutions for the infrastructure design of intercity passenger travel. HSR is a capital-intensive infrastructure, in which multiple subsystems are closely integrated. Also, HSR operation lasts for a long period, and its performance indicators are continuously altered by incremental updates. -

Missouri Blue Ribbon Panel on Hyperloop

Chairman Lt. Governor Mike Kehoe Vice Chairman Andrew G. Smith Panelists Jeff Aboussie Cathy Bennett Tom Blair Travis Brown Mun Choi Tom Dempsey Rob Dixon Warren Erdman Rep. Travis Fitzwater Michael X. Gallagher Rep. Derek Grier Chris Gutierrez Rhonda Hamm-Niebruegge Mike Lally Mary Lamie Elizabeth Loboa Sen. Tony Luetkemeyer MISSOURI BLUE RIBBON Patrick McKenna Dan Mehan Joe Reagan Clint Robinson PANEL ON HYPERLOOP Sen. Caleb Rowden Greg Steinhoff Report prepared for The Honorable Elijah Haahr Tariq Taherbhai Leonard Toenjes Speaker of the Missouri House of Representatives Bill Turpin Austin Walker Ryan Weber Sen. Brian Williams Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 A National Certification Track in Missouri .................................................................................................... 8 Track Specifications ................................................................................................................................. 10 SECTION 1: International Tube Transport Center of Excellence (ITTCE) ................................................... 12 Center Objectives ................................................................................................................................ 12 Research Areas ................................................................................................................................... -

Transportation Planning for the Richmond–Charlotte Railroad Corridor

VOLUME I Executive Summary and Main Report Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the Richmond–Charlotte Railroad Corridor Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation January 2004 Disclaimer: This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation solely in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof, nor does it express any opinion whatsoever on the merit or desirability of the project(s) described herein. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Any trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this report. Note: In an effort to better inform the public, this document contains references to a number of Internet web sites. Web site locations change rapidly and, while every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of these references as of the date of publication, the references may prove to be invalid in the future. Should an FRA document prove difficult to find, readers should access the FRA web site (www.fra.dot.gov) and search by the document’s title or subject. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FRA/RDV-04/02 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date January 2004 Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the Richmond–Charlotte Railroad Corridor⎯Volume I 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Authors: 8. Performing Organization Report No. For the engineering contractor: Michael C. Holowaty, Project Manager For the sponsoring agency: Richard U. Cogswell and Neil E. Moyer 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. -

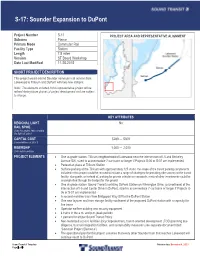

Sounder Expansion to Dupont

S-17: Sounder Expansion to DuPont Project Number S-17 PROJECT AREA AND REPRESENTATIVE ALIGNMENT Subarea Pierce Primary Mode Commuter Rail Facility Type Station Length 7.8 miles Version ST Board Workshop Date Last Modified 11-25-2015 SHORT PROJECT DESCRIPTION This project would extend Sounder commuter rail service from Lakewood to Tillicum and DuPont with two new stations. Note: The elements included in this representative project will be refined during future phases of project development and are subject to change. KEY ATTRIBUTES REGIONAL LIGHT No RAIL SPINE Does this project help complete the light rail spine? CAPITAL COST $289 — $309 Cost in Millions of 2014 $ RIDERSHIP 1,000 — 2,000 2040 daily boardings PROJECT ELEMENTS · One at-grade station: Tillicum neighborhood of Lakewood near the intersection of I-5 and Berkeley Avenue SW, sized to accommodate 7-car trains or longer if Projects S-06 or S-07 are implemented · Pedestrian plaza at Tillicum Station · Surface parking at the Tillicum with approximately 125 stalls; the scope of the transit parking components included in this project could be revised to include a range of strategies for providing rider access to the transit facility; along with, or instead of, parking for private vehicles or van pools, a mix of other investments could be accomplished through the budget for this project · One at-grade station: Sound Transit’s existing DuPont Station on Wilmington Drive, just northeast of the intersection of I-5 and Center Drive in DuPont, sized to accommodate 7-car trains or longer if Projects S- 06 or S-07 are implemented · A second mainline track from Bridgeport Way SW to the DuPont Station · One new layover and train storage facility southwest of the proposed DuPont station with a capacity for five trains · Operator welfare building and security equipment · 4 trains in the a.m. -

2021 Georgia State Rail Plan

State Rail Plan Georgia State Rail Plan Final Report Master Contract #: TOOIP1900173 PI # 0015886 State Rail Plan Update – FY 2018 4/6/2021 State Rail Plan Contents 1. The Role of Rail in Statewide Transportation ......................................................................................... 1-7 1.1. Purpose and Content ...................................................................................................................... 1-7 1.2. Multimodal Transportation System Goals ...................................................................................... 1-8 1.3. Role of Rail in Georgia’s Transportation Network .......................................................................... 1-8 1.4. Role of Passenger Rail in Georgia Transportation Network ......................................................... 1-16 1.5. Institutional Governance Structure of Rail in Georgia ................................................................. 1-19 1.6. Role of Federal Agencies .............................................................................................................. 1-29 2. Georgia’s Existing Rail System ................................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1. Description and Inventory .............................................................................................................. 2-1 2.2. Trends and Forecasts ................................................................................................................... -

HQ-2017-1239 Final.Pdf

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety Accident and Analysis Branch Accident Investigation Report HQ-2017-1239 Amtrak 501 DuPont, Washington December 18, 2017 Note that 49 U.S.C. §20903 provides that no part of an accident or incident report, including this one, made by the Secretary of Transportation/Federal Railroad Administration under 49 U.S.C. §20902 may be used in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report. U.S. Department of Transportation FRA File #HQ-2017-1239 Federal Railroad Administration FRA FACTUAL RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT SYNOPSIS On December 18, 2017, at 7:33 a.m., PST, southbound National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) Passenger Train Number 501 (Train 501) derailed in an 8-degree, 22-minute, left-hand curve at Milepost (MP) 19.86 on the Central Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority, Sounder Commuter Rail (Sound Transit) Lakewood Subdivision, in DuPont, Washington. The lead locomotive and 12 cars derailed, with some sliding down an embankment, and some landing on the southbound lanes of Interstate 5, colliding with several highway vehicles. Train 501 is part of the Amtrak Cascades passenger train service funded by the States of Washington and Oregon. The Cascades passenger train service operates between Vancouver, British Columbia, and Eugene, Oregon, using Talgo, Inc. (Talgo) passenger equipment. DuPont, Washington, is located approximately 18 miles southwest of Tacoma, Washington. Sound Transit is the host railroad to Amtrak on the Lakewood Subdivision, which is approximately 20 miles in length from Tacoma to DuPont. Train 501 was traveling from Seattle, Washington, to Portland, Oregon, over the Point Defiance Bypass track between Tacoma and DuPont.