Amtrak CEO Flynn House Railroads Testimony May 6 20201

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harrisburg Line Capacity Improvements Upgrade of Track 2 from Glen Interlocking to Thorn Interlocking

HARRISBURG LINE CAPACITY IMPROVEMENTS UPGRADE OF TRACK 2 FROM GLEN INTERLOCKING TO THORN INTERLOCKING FEDERAL RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION FEDERAL-STATE PARTNERSHIP FOR STATE OF GOOD REPAIR PROGRAM GRANT APPLICATION Lead Applicant: Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) Joint Applicant: Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) FEDERAL FUNDING REQUESTED: $8,337,500 (50%) PROPOSED NON-FEDERAL MATCH: $8,337,500 (50%) TOTAL PROJECT COST: $16,675,000 PROJECT LOCATION: Caln Township, Downingtown Borough, East Caln Township, West Whiteland Township, & East Whiteland Township in Chester County, Pennsylvania - 6th Congressional District No Federal Grant Application Previously Submitted for this Project Table of Contents I. Project Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Project Funding ..................................................................................................................................... 2 III. Applicant Eligibility ............................................................................................................................... 3 IV. NEC Project Eligibility ........................................................................................................................... 3 V. Detailed Project Description ................................................................................................................ 5 VI. Project Location ................................................................................................................................. -

Bus and Shared-Ride Taxi Use in Two Small Urban Areas

Bus and Shared-Ride Taxi Use in Two Small Urban Areas David P. Middendorf, Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and Company Kenneth W. Heathington, University of Tennessee The demand for publicly owned fixed-route. fixed-schedule bus service are used for work and business-related trips to and was compared with tho demand for privately owned shared-ride taxi ser within CBDs and for short social, shopping, medical, vice in Davenport. Iowa, and Hicksville, New York, through on-board and personal business trips. surveys end cab company dispatch records and driver logs. The bus and In many small cities and in many suburbs of large slmrcd·ride taxi systems in Davenport com11eted for the off.peak-period travel market. During off-peak hours, the taxis tended to attract social· metropol.il;e:H!:i, l.lus~s nd taxicabs operate within tlie recreation, medical, and per onal business trips between widely scattered same jlu·isclictions and may compete for the same public origins and destinations, while the buses tended 10 attract shopping and transportation market. Two examples of small commu personal business trips to the CBD. The shared-ride taxi system in Hicks· nities in which buses and ta.xis coexist are Davenport, ville, in addition to providing many-to·many service, competed with the Iowa, and Hicksville, New York. The markets, eco counlywide bus system as a feeder system to the Long Island commuter nomic characteristics, organization, management, and railroad network. In each study area, the markets of each mode of public operation of the taxicab systems sel'Ving these commu transportation were similar. -

FY20-Fed-State-SOGR-Project-Recipients

FY 2020 Federal-State Partnership for State of Good Repair Grant Program California — San Diego Next Generation Signaling and Grade Crossing Modernization Up to $9,836,917 North County Transit District Replaces and upgrades obsolete signal, train control, and crossing equipment on a 60-mile section of North County Transit District right-of-way the carrier shares with Amtrak intercity service and freight rail. Brings signal and train control components into a state of good repair, including installing new signal houses, signals, and cabling. Replaces components at more than 15 grade crossings along the corridor. California — Pacific Surfliner Corridor Rehabilitation and Service Reliability Up to $31,800,000 Southern California Regional Rail Authority Rehabilitates track, structures, and grade crossings in Ventura County and northern Los Angeles County on infrastructure used by Amtrak intercity service, Metrolink commuter service, and BNSF freight service. Work for member agency Ventura County Transportation Commission includes track, tie, ballast, and culvert replacements, grade crossing rehabilitation, and tunnel track and structure replacements. Reduces trip times, increases reliability, and improves safety by reducing need for slow orders and conflicts at grade crossings in the corridor. Connecticut — Walk Bridge Replacement Up to $79,700,000 Connecticut Department of Transportation & Amtrak Replaces the Connecticut-owned movable Norwalk River Bridge, built in 1896, with two, independent, two-track, vertical lift rail bridges in Norwalk, Connecticut. Includes associated embankment and retaining wall improvements on the bridge approaches, new catenary structures, and signal system upgrades. The existing bridge is beyond its useful life and prone to malfunctions, especially during opening or closing. The replacement will reduce slow orders, reduce the risk of service disruptions, and improve resiliency to extreme weather events. -

Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary

Final Report New Haven Hartford Springfield Commuter Rail Implementation Study 2 Existing Conditions Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary This chapter is a summary of the existing conditions report, necessary for comprehension of the remaining chapters. The entire report can be found in Appendix B of this report. 2.1 Existing Passenger Services on the Line The only existing passenger rail service on the Springfield Line is a regional service operated by Amtrak. Schedules for alternatives in Chapter 3 and the Recommended Action in Chapter 4 include current Amtrak service. Most Amtrak service on the line is shuttle trains, running between Springfield and New Haven, where they connect with other Amtrak Northeast Corridor trains. One round-trip train each day operates through the corridor to Boston to the north and Washington to the south. One round trip train each day operates to and from St. Albans, Vermont from New Haven. The trains also permit connections at New Haven with Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (Washington to Boston) service, as well as Metro North service to New York, and Shore Line East local commuter service to New London. Departures are spread throughout the day, with trains typically operating at intervals of two to three hours. Springfield line services are designed as extensions of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor service, and are not scheduled to serve local commuter trips (home to work trips). The Amtrak fare structure was substantially reduced in price since this study began. The original fare structure from November 2002 was shown in the existing conditions report, which can be found in Appendix B. -

Public Transportation

TRANSPORTATION NETWORK DIRECTORY FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES AND ADULTS 50+ MONTGOMERY COUNTY, MD PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION Montgomery County, Maryland (‘the County’) cannot guarantee the relevance, completeness, accuracy, or timeliness of the information provided on the non-County links. The County does not endorse any non-County organizations' products, services, or viewpoints. The County is not responsible for any materials stored on other non-County web sites, nor is it liable for any inaccurate, defamatory, offensive or illegal materials found on other Web sites, and that the risk of injury or damage from viewing, hearing, downloading or storing such materials rests entirely with the user. Alternative formats of this document are available upon request. This is a project of the Montgomery County Commission on People with Disabilities. To submit an update, add or remove a listing, or request an alternative format, please contact: [email protected], 240-777-1246 (V), MD Relay 711. MetroAccess and Abilities-Ride MetroAccess Paratransit – Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) MetroAccess is a shared-ride, door-to-door public transportation service for people who are unable to use fixed-route public transit due to disability. "Shared ride" means that multiple passengers may ride together in the same vehicle. The service provides daily trips throughout the Transit Zone in the Washington Metropolitan region. The Transit Zone consists of the District of Columbia, Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties in Maryland, Arlington and Fairfax Counties and the cities of Alexandria, Fairfax and Falls Church in Northern Virginia. Rides are offered in the same service areas and during the same hours of operation as Metrorail and Metrobus. -

Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

PB88-916301 NATIONAL TRANSPORT SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT REAR-END COLLISION OF AMTRAK PASSENGER TRAIN 94, THE COLONIAL AND CONSOLIDATED RAIL CORPORATION FREIGHT TRAIN ENS-121, ON THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR CHASE, MARYLAND JANUARY 4, 1987 NTSB/RAR-88/01 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2.Government Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/RAR-88/01 . PB88-916301 Title and Subtitle Railroad Accident Report^ 5-Report Date Rear-end Collision of'*Amtrak Passenger Train 949 the January 25, 1988 Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight -Performing Organization Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Code Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987 -Performing Organization 7. "Author(s) ~~ Report No. Performing Organization Name and Address 10.Work Unit No. National Transportation Safety Board Bureau of Accident Investigation .Contract or Grant No. Washington, D.C. 20594 k3-Type of Report and Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Iroad Accident Report lanuary 4, 1987 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 1*+.Sponsoring Agency Code 15-Supplementary Notes 16 Abstract About 1:16 p.m., eastern standard time, on January 4, 1987, northbound Conrail train ENS -121 departed Bay View yard at Baltimore, Mary1 and, on track 1. The train consisted of three diesel-electric freight locomotive units, all under power and manned by an engineer and a brakeman. Almost simultaneously, northbound Amtrak train 94 departed Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore. Train 94 consisted of two electric locomotive units, nine coaches, and three food service cars. In addition to an engineer, conductor, and three assistant conductors, there were seven Amtrak service employees and about 660 passengers on the train. -

Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options

Advocacy Sustainability Partnerships Fort Washington Office Park Transportation Demand Management Plan Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options Prepared by GVF GVF July 2017 Contents Executive Summary and Key Findings ........................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Sources ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 ArcMap Geocoding and Data Analysis .................................................................................................. 6 Travel Times Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 7 Data Collection .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Employee Commuter Survey Results ................................................................................................ 7 2. Office Park Companies Outreach Results ......................................................................................... 7 3. Office Park -

Eastwick Intermodal Center

Eastwick Intermodal Center January 2020 New vo,k City • p-~ d DELAWARE VALLEY DVRPC's vision for the Greater Ph iladelphia Region ~ is a prosperous, innovative, equitable, resilient, and fJ REGl!rpc sustainable region that increases mobility choices PLANNING COMMISSION by investing in a safe and modern transportation system; Ni that protects and preserves our nat ural resources w hile creating healthy communities; and that fosters greater opportunities for all. DVRPC's mission is to achieve this vision by convening the widest array of partners to inform and facilitate data-driven decision-making. We are engaged across the region, and strive to be lea ders and innovators, exploring new ideas and creating best practices. TITLE VI COMPLIANCE / DVRPC fully complies with Title VJ of the Civil Rights Act of 7964, the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 7987, Executive Order 72898 on Environmental Justice, and related nondiscrimination mandates in all programs and activities. DVRPC's website, www.dvrpc.org, may be translated into multiple languages. Publications and other public documents can usually be made available in alternative languages and formats, if requested. DVRPC's public meetings are always held in ADA-accessible facilities, and held in transit-accessible locations whenever possible. Translation, interpretation, or other auxiliary services can be provided to individuals who submit a request at least seven days prior to a public meeting. Translation and interpretation services for DVRPC's projects, products, and planning processes are available, generally free of charge, by calling (275) 592-7800. All requests will be accommodated to the greatest extent possible. Any person who believes they have been aggrieved by an unlawful discriminatory practice by DVRPC under Title VI has a right to file a formal complaint. -

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi M.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2011 B.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2009 Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2016 © 2016 Tatsuya Doi. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________________ Institute for Data, Systems, and Society May 6, 2016 Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Joseph M. Sussman JR East Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Olivier L. de Weck Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: _________________________________________________________________________ John N. Tsitsiklis Clarence J. Lebel Professor of Electrical Engineering IDSS Graduate Officer 1 2 Interaction of Lifecycle Properties In High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society on May 6, 2016 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems ABSTRACT High-Speed Rail (HSR) has been expanding throughout the world, providing various nations with alternative solutions for the infrastructure design of intercity passenger travel. HSR is a capital-intensive infrastructure, in which multiple subsystems are closely integrated. Also, HSR operation lasts for a long period, and its performance indicators are continuously altered by incremental updates. -

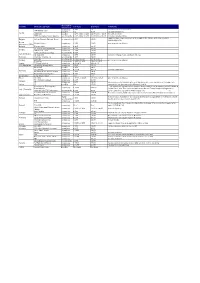

Reservations PUBLISHED Overview 30 March 2015.Xlsx

Reservation Country Domestic day train 1st Class 2nd Class Comments Information compulsory € 8,50 n.a. on board only; free newspaper WESTbahn trains possible n.a. € 5,00 via www.westbahn.at Austria ÖBB trains possible € 3,00 online / € 3,50 € 3,00 online / € 3,50 free wifi on rj-trains ÖBB Intercitybus Graz-Klagenfurt recommended € 3,00 online / € 3,50 € 3,00 online / € 3,50 first class includes drinks supplement per single journey. Can be bought in the station, in the train or online: Belgium to/from Brussels National Airport no reservation € 5,00 € 5,00 www.belgianrail.be Bosnia- Regional trains compulsory € 1,50 € 1,50 price depends on distance Herzegovina (ZRS) Bulgaria Express trains compulsory € 0,25 € 0,25 IC Zagreb - Osijek/Varazdin compulsory € 1,00 € 1,00 Croatia ICN Zagreb - Split compulsory € 1,00 € 1,00 IC/EC (domestic journeys) recommended € 2,00 € 2,00 Czech Republic SC SuperCity compulsory € 8,00 € 8,00 includes newspaper and catering in 1st class Denmark InterCity / InterCity Lyn recommended € 4,00 € 4,00 InterCity recommended € 1,84 to €5,63 € 1,36 to € 4,17 Finland price depends on distance Pendolino recommended € 3,55 to € 6,79 € 2,63 to € 5,03 France TGV and Intercités compulsory € 9 to € 18 € 9 to € 18 FYR Macedonia IC 540/541 Skopje-Bitola compulsory € 0,50 € 0,50 EC/IC/ICE possible € 4,50 € 4,50 ICE Sprinter compulsory € 11,50 € 11,50 includes newspapers Germany EC 54/55 Berlin-Gdansk-Gdynia compulsory € 4,50 € 4,50 Berlin-Warszawa Express compulsory € 4,50 € 4,50 Great Britain Long distance trains possible Free Free Greece Inter City compulsory € 7,10 to € 20,30 € 7,10 to € 20,30 price depends on distance EC (domestic jouneys) compulsory € 3,00 € 3,00 Hungary IC compulsory € 3,00 € 3,00 when purchased in Hungary, price may depend on pre-sales and currency exchange rate Ireland IC possible n/a € 5,00 reservations can be made online @ www.irishrail.ie Frecciarossa, Frecciargento, → all compulsory and optional reservations for passholders can be purchased via Trenitalia at compulsory € 10,00 € 10,00 Frecciabianca "Global Pass" fare. -

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo-Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report – Discussion Draft 2 1

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo- Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report DISCUSSION DRAFT (Quantified Model Data Subject to Refinement) Table of Contents 1. Project Background: ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Early Study Efforts and Initial Findings: ................................................................................................ 5 3. Background Data Collection Interviews: ................................................................................................ 6 4. Fixed-Facility Capital Cost Estimate Range Based on Existing Studies: ............................................... 7 5. Selection of Single Route for Refined Analysis and Potential “Proxy” for Other Routes: ................ 9 6. Legal Opinion on Relevant Amtrak Enabling Legislation: ................................................................... 10 7. Sample “Timetable-Format” Schedules of Four Frequency New York-Chicago Service: .............. 12 8. Order-of-Magnitude Capital Cost Estimates for Platform-Related Improvements: ............................ 14 9. Ballpark Station-by-Station Ridership Estimates: ................................................................................... 16 10. Scoping-Level Four Frequency Operating Cost and Revenue Model: .................................................. 18 11. Study Findings and Conclusions: ......................................................................................................... -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A.