Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.2 Pointwork Configurations in the Following Paragraphs Some of the More Maintenance Is Straightforward

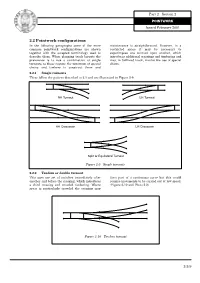

Part 2 Section 2 POINTWORK Issued February 2001 2.2 Pointwork configurations In the following paragraphs some of the more maintenance is straightforward. However, in a common pointwork configurations are shown restricted space it may be necessary to together with the accepted terminology used to superimpose one turnout upon another, which describe them. When planning track layouts the introduces additional crossings and timbering and preference is to use a combination of single may, in bullhead track, involve the use of special turnouts as these require the minimum of special chairs. chairs and timbers to construct them and 2.2.1 Single turnouts These follow the pattern described in 2.1 and are illustrated in Figure 2-9. RH Turnout LH Turnout RH Crossover LH Crossover Split or Equilateral Turnout Figure 2-9 Single turnouts 2.2.2 Tandem or double turnout This uses one set of switches immediately after form part of a continuous curve but this would another and before the crossing, which introduces require movements to be carried out at low speed. a third crossing and crowded timbering. Where (Figure 2-10 and Photo 2.2) space is particularly crowded the crossing may Figure 2-10 Tandem turnout 2-2-9 2.2.3 Three-throw turnout Photo 2.2 A double tandem turnout leading off from a double There is a nomenclature problem here slip at Stowmarket Goods Yard. as the 3-throw yields the same outcome (NRM Windwood Collection GE1005) as the double turnout. It uses a left hand and a right hand set of switches that are superimposed to divide three ways together in symmetrical form. -

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 71.9 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department 10-88 Bomb Threat 10-16 -

Metro Rail Design Criteria Section 10 Operations

METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 OPERATIONS METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 / OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 10.1 INTRODUCTION 1 10.2 DEFINITIONS 1 10.3 OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE PLAN 5 Metro Baseline 10- i Re-baseline: 06/15/10 METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 / OPERATIONS OPERATIONS 10.1 INTRODUCTION Transit Operations include such activities as scheduling, crew rostering, running and supervision of revenue trains and vehicles, fare collection, system security and system maintenance. This section describes the basic system wide operating and maintenance philosophies and methodologies set forth for the Metro Rail Projects, which shall be used by designer in preparation of an Operations and Maintenance Plan. An initial Operations and Maintenance Plan (OMP) is developed during the environmental phase and is based on ridership forecasts produced during this early planning phase of a project. From this initial Operations and Maintenance plan, headways are established that are to be evaluated by a rail operations simulation upon which design and operating headways can be established to confirm operational goals for light and heavy rail systems. The Operations and Maintenance Plan shall be developed in order to design effective, efficient and responsive transit system. The operations criteria and requirements established herein represent Metro’s Rail Operating Requirements / Criteria applicable to all rail projects and form the basis for the project-specific operational design decisions. They shall be utilized by designer during preparation of Operations and Maintenance Plan. Any proposed deviation to Design Criteria cited herein shall be approved by Metro, as represented by the Change Control Board, consisting of management responsible for project construction, engineering and management, as well as daily rail operations, planning, systems and vehicle maintenance with appropriate technical expertise and understanding. -

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary

Final Report New Haven Hartford Springfield Commuter Rail Implementation Study 2 Existing Conditions Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary This chapter is a summary of the existing conditions report, necessary for comprehension of the remaining chapters. The entire report can be found in Appendix B of this report. 2.1 Existing Passenger Services on the Line The only existing passenger rail service on the Springfield Line is a regional service operated by Amtrak. Schedules for alternatives in Chapter 3 and the Recommended Action in Chapter 4 include current Amtrak service. Most Amtrak service on the line is shuttle trains, running between Springfield and New Haven, where they connect with other Amtrak Northeast Corridor trains. One round-trip train each day operates through the corridor to Boston to the north and Washington to the south. One round trip train each day operates to and from St. Albans, Vermont from New Haven. The trains also permit connections at New Haven with Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (Washington to Boston) service, as well as Metro North service to New York, and Shore Line East local commuter service to New London. Departures are spread throughout the day, with trains typically operating at intervals of two to three hours. Springfield line services are designed as extensions of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor service, and are not scheduled to serve local commuter trips (home to work trips). The Amtrak fare structure was substantially reduced in price since this study began. The original fare structure from November 2002 was shown in the existing conditions report, which can be found in Appendix B. -

At Station Drive 247 STATION DRIVE, WESTWOOD, MA

at station drive 247 STATION DRIVE, WESTWOOD, MA Summit at Station Drive is situated in a desirable and amenity-rich environment, surrounded by a wide variety of retail brands and dining options in University Station, as well as hotels and residential apartments. With direct access from 128/I - 95 and directly adjacent to the 128 Commuter Rail/Amtrak Station and Acela, as well as the availability of ample parking, Summit at Station Drive defines work-life balance. BUILDING SPECIFICATIONS Total Building Size: 368,000 SF Year Built: 2001 Parking: 3.09 spaces per 1,000 RSF, covered parking available HVAC: Gas fired roof top units, VAV boxes with electric reheat coils Ceiling Height: 9’ Loading: 1 dock on each east and west sides, covered, lift gates Power: 4000 amp service Generator: 1000 kw on west side, 350 kw on east side Telecommunications: Verizon and RCN Elevators: 2 passenger and 1 freight elevator on both east and west sides Electric: Eversource On-site Amenities: Full-service cafeteria with outdoor seating, fitness room with lockers & showers WESTWOOD, MA Established in 1897, Westwood is a bustling community of over 14,500 residents located 12 miles southwest of Boston. Westwood is situated at the junction of I-95/ Route 128 and I-93, providing an excellent location with easy access to Boston and Providence, as well as two commuter rail lines and full MBTA bus service on Routes 1 and 1A (Washington Street). Westwood is home to over two hundred businesses in established commercial areas, each varied in character. CNN/Money and Money magazine recently ranked Westwood 13th on its list of the “100 Best Places to Live in the United States”. -

Feasibility Study for Intercity Rail Service to T.F. Green Airport April 2017

Feasibility Study for Intercity Rail Service to : RIAC Credit T.F. Green Airport Photo Infrastructure and Investment April Development Department 2017 and Feasibility Study for Intercity Rail Service to T.F. Green Airport April 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CONTEXT FOR STUDY .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 SCOPE FOR STUDY ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 REFERENCE STUDIES .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 2 EXISTING RAIL SERVICE ............................................................................................................................ 3 2.1 RHODE ISLAND ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 SOUTHEASTERN CONNECTICUT .......................................................................................................................................... -

The Signal Bridge

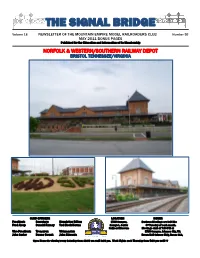

THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Volume 18 NEWSLETTER OF THE MOUNTAIN EMPIRE MODEL RAILROADERS CLUB Number 5B MAY 2011 BONUS PAGES Published for the Education and Information of Its Membership NORFOLK & WESTERN/SOUTHERN RAILWAY DEPOT BRISTOL TENNESSEE/VIRGINIA CLUB OFFICERS LOCATION HOURS President: Secretary: Newsletter Editor: ETSU Campus, Business Meetings are held the Fred Alsop Donald Ramey Ted Bleck-Doran: George L. Carter 3rd Tuesday of each month. Railroad Museum Meetings start at 7:00 PM at Vice-President: Treasurer: Webmaster: ETSU Campus, Johnson City, TN. John Carter Duane Swank John Edwards Brown Hall Science Bldg, Room 312, Open House for viewing every Saturday from 10:00 am until 3:00 pm. Work Nights each Thursday from 5:00 pm until ?? APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Page 2 APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Page 3 APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE II scheme. The "stripe" style paint schemes would be used on AMTRAK PAINT SCHEMES Amtrak for many more years. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Phase II Amtrak paint schemes or "Phases" (referred to by Amtrak), are a series of livery applied to the outside of their rolling stock in the United States. The livery phases appeared as different designs, with a majority using a red, white, and blue (the colors of the American flag) format, except for promotional trains, state partnership routes, and the Acela "splotches" phase. The first Amtrak Phases started to emerge around 1972, shortly after Amtrak's formation. Phase paint schemes Phase I F40PH in Phase II Livery Phase II was one of the first paint schemes of Amtrak to use entirely the "stripe" style. -

Evidence from Ghanaian Railways∗

Colonial Investments and Long-Term Development in Africa: Evidence from Ghanaian Railways∗ Remi JEDWABa Alexander MORADIb a Department of Economics, George Washington University, and STICERD, London School of Economics b Department of Economics, University of Sussex This Version: October 14th, 2012 Abstract: What is the impact of colonial public investments on long-term development? We investigate this issue by looking at the impact of railway construction on economic develop- ment in Ghana. Two railway lines were built by the British to link the coast to mining areas and the hinterland city of Kumasi. Using panel data at a fine spatial level over one century (11x11 km grid cells in 1891-2000), we find a strong effect of rail connectivity on the pro- duction of cocoa, the country’s main export commodity, and development, which we proxy by population and urban growth. First, we exploit various strategies to ensure our effects are causal: we show that pre-railway transport costs were prohibitively high, we provide ev- idence that line placement was exogenous, we find no effect for a set of placebo lines, and results are robust to instrumentation and nearest neighbor matching. Second, transportation infrastructure investments had large welfare effects for Ghanaians during the colonial period. Colonization meant both extraction and development in this context. Third, railway con- struction had a persistent impact: railway cells are more developed today despite a complete displacement of rail by other means of transport. We investigate the various channels of path dependence, including demographic growth, industrialization or infrastructure investments. Keywords: Colonialism; Africa; Transportation Infrastructure; Trade JEL classification: F54; O55; O18; R4; F1 ∗Remi Jedwab, George Washington University and STICERD, London School of Economics (e-mail: [email protected]). -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Reservations PUBLISHED Overview 30 March 2015.Xlsx

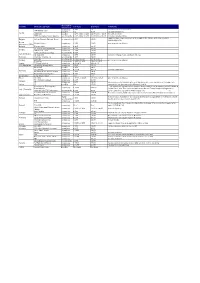

Reservation Country Domestic day train 1st Class 2nd Class Comments Information compulsory € 8,50 n.a. on board only; free newspaper WESTbahn trains possible n.a. € 5,00 via www.westbahn.at Austria ÖBB trains possible € 3,00 online / € 3,50 € 3,00 online / € 3,50 free wifi on rj-trains ÖBB Intercitybus Graz-Klagenfurt recommended € 3,00 online / € 3,50 € 3,00 online / € 3,50 first class includes drinks supplement per single journey. Can be bought in the station, in the train or online: Belgium to/from Brussels National Airport no reservation € 5,00 € 5,00 www.belgianrail.be Bosnia- Regional trains compulsory € 1,50 € 1,50 price depends on distance Herzegovina (ZRS) Bulgaria Express trains compulsory € 0,25 € 0,25 IC Zagreb - Osijek/Varazdin compulsory € 1,00 € 1,00 Croatia ICN Zagreb - Split compulsory € 1,00 € 1,00 IC/EC (domestic journeys) recommended € 2,00 € 2,00 Czech Republic SC SuperCity compulsory € 8,00 € 8,00 includes newspaper and catering in 1st class Denmark InterCity / InterCity Lyn recommended € 4,00 € 4,00 InterCity recommended € 1,84 to €5,63 € 1,36 to € 4,17 Finland price depends on distance Pendolino recommended € 3,55 to € 6,79 € 2,63 to € 5,03 France TGV and Intercités compulsory € 9 to € 18 € 9 to € 18 FYR Macedonia IC 540/541 Skopje-Bitola compulsory € 0,50 € 0,50 EC/IC/ICE possible € 4,50 € 4,50 ICE Sprinter compulsory € 11,50 € 11,50 includes newspapers Germany EC 54/55 Berlin-Gdansk-Gdynia compulsory € 4,50 € 4,50 Berlin-Warszawa Express compulsory € 4,50 € 4,50 Great Britain Long distance trains possible Free Free Greece Inter City compulsory € 7,10 to € 20,30 € 7,10 to € 20,30 price depends on distance EC (domestic jouneys) compulsory € 3,00 € 3,00 Hungary IC compulsory € 3,00 € 3,00 when purchased in Hungary, price may depend on pre-sales and currency exchange rate Ireland IC possible n/a € 5,00 reservations can be made online @ www.irishrail.ie Frecciarossa, Frecciargento, → all compulsory and optional reservations for passholders can be purchased via Trenitalia at compulsory € 10,00 € 10,00 Frecciabianca "Global Pass" fare.