2021 Georgia State Rail Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Chief – El Capitan See Page 4 for Details

AUGUST- lyerlyer SEPTEMBER 2020 Ready for Boarding! Late 1960s Combined Super Chief – El Capitan see page 4 for details FLYER SALE ENDS 9-30-20 Find a Hobby Shop Near You! Visit walthers.com or call 1-800-487-2467 WELCOME CONTENTS Chill out with cool new products, great deals and WalthersProto Super Chief/El Capitan Pages 4-7 Rolling Along & everything you need for summer projects in this issue! Walthers Flyer First Products Pages 8-10 With two great trains in one, reserve your Late 1960s New from Walthers Pages 11-17 Going Strong! combined Super Chief/El Capitan today! Our next HO National Model Railroad Build-Off Pages 18 & 19 Railroads have a long-standing tradition of getting every last WalthersProto® name train features an authentic mix of mile out of their rolling stock and engines. While railfans of Santa Fe Hi-Level and conventional cars - including a New From Our Partners Pages 20 & 21 the 1960s were looking for the newest second-generation brand-new model, new F7s and more! Perfect for The Bargain Depot Pages 22 & 23 diesels and admiring ever-bigger, more specialized freight operation or collection, complete details start on page 4. Walthers 2021 Reference Book Page 24 cars, a lot of older equipment kept rolling right along. A feature of lumber traffic from the 1960s to early 2000s, HO Scale Pages 25-33, 36-51 Work-a-day locals and wayfreights were no less colorful, the next run of WalthersProto 56' Thrall All-Door Boxcars N Scale Pages 52-57 with a mix of earlier engines and equipment that had are loaded with detail! Check out these layout-ready HO recently been repainted and rebuilt. -

2.0 Current Freight Rail System and Services in Florida

Investment Element of the 2010 Florida Rail System Plan 2.0 Current Freight Rail System and Services in Florida 2.1 Overview The Florida rail system is comprised of 2,786 miles of mainline track, which are owned by 15 operating line-haul railroads and terminal or switching companies, as well as 81 miles owned by the State of Florida. Florida’s rail system includes 2 Class I Railroads (CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Corporation), 1 Class II (Florida East Coast Railway), 11 Class III (Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway AN Railway, Bay Line Railroad, First Coast Railroad, Florida West Coast Railroad, Florida Central Railroad, Florida Midland Railroad, Florida Northern Railroad, Georgia and Florida Railway, Seminole Gulf Railway, and South Central Florida Express) and 1 railroad specializing in switching and terminals (Talleyrand Terminal).9 The largest operator in the State is CSX Transportation, which owns more than 53 percent of the statewide track mileage. In 2008, Florida’s railroads carried nearly 1.6 million carloads – 19 percent less than in 2006 – and approximately 83 million tons of freight, representing a 25 million ton (23 percent) decrease from 2006.10 During that year, railroads handled freight equivalent to roughly 5.0 million heavy trucks.11 Nonetheless, railroads continue to support thousands of jobs throughout the State and assist Florida’s industries to remain competitive with international and domestic markets for fertilizer, construction rock, consumer goods, paper products, processed 9 U.S. Class I Railroads are line-haul freight railroads with 2007 operating revenue in excess of $359.6 million (2006 operating revenues exceeding $346.7 million). -

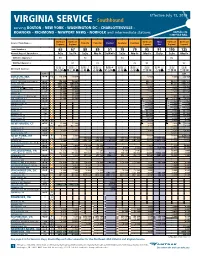

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System > See Page 46 >

THENational Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers CHAMPION July 2013 Hair Microscopy Review Project An Historic Breakthrough For Law Enforcement and A Daunting Challenge For the Defense Bar Eliminating Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System > See page 46 > LAS VEGAS, NV > > SEE PAGE 3 October 3-5, 2013 / NACDL & NCDD’s 17th Annual DWI Means Defend With Ingenuity Conference SAVANNAH, GA > > SEE PAGE 20 October 16-19, 2013 / NACDL’s 2013 Fall Meeting & Seminar WASHINGTON, DC > > SEE BROCHURE October 24-25, 2013 / 9th Annual Defending the White Collar Case LAS VEGAS, NV > > SEE PAGE 29 November 21-22, 2013 / NACDL’s 6th Annual Defending the Modern Drug Case Conference ASPEN, CO > > SEE PAGE 53 January 12-17, 2014 / 34th Annual Advanced Criminal Law Seminar NEW ORLEANS, LA > > SEE PAGE 60 March 5-8, 2014 / NACDL’s 2014 Collateral Consequences Conference & Midwinter Meeting WWW .NACDL .OR G ©Bill Fritsch | Artville Similarly, eliminating racial disparities in the criminal justice system can be achieved by recognizing the power we all possess to get rid of personal biases and structural racism in the criminal justice system. In essence, every police officer, prosecutor, defense attorney, lawyer, judge, juror, and community mem - ber has to do more, care more, and be more under - standing and willingly acknowledge the biases every - one possesses. In October 2012 NACDL and other organizations sponsored a conference entitled Criminal Justice in Racial Disparities the 21st Century: Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System. The people who attended came to the table acknowledging that racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice The Answer Lies Within system exist. -

General Freight Tariff 5000

GENERAL FREIGHT TARIFF 5000 GENERAL FREIGHT TARIFF 5000 NAMING RULES AND CHARGES GOVERNING DEMURRAGE, SWITCHING AND OTHER ACCESSORIAL AND TERMINAL SERVICES For the following Subscribing Carriers: Railroad Alabama & Tennessee River Railway, LLC ATN Brownsville & Rio Grande International Railroad BRG Cleveland & Cuyohoga Railway, LLC CCRL Chicago Rail Link, LLC CRL Cleveland Harbor Belt Railroad, LLC CHB Central Texas & Colorado River Railway, LLC CTXR Decatur Central Railway, LLC DCC Fulton County Railway, LLC FCR Georgia & Florida Railway, LLC GFRR Georgia Woodlands Railway, LLC GWRC Great Western Railway of Colorado, LLC GWR Illinois Railway, LLC IR Kettle Falls International Railway, LLC KFR Manufacturers' Junction Railway, LLC MJ Nebraska, Kansas, & Colorado Railway, LLC NKCR Newburgh & South Shore Railroad, LLC NSR Northern Ohio & Western Railway, LLC NOW Panhandle Northern Railroad, LLC PNR Peru Industrial Railroad, LLC PIR Sand Springs Railway Company SS Stockton Terminal and Eastern Railroad STE Winchester & Western Railroad, LLC WW This Tariff is also applicable on intrastate traffic, except where expressly provided to the contrary in connection with particular rates and provisions contained herein. ISSUED: December 10, 2019 EFFECTIVE: January 1, 2020 ISSUED BY: OmniTRAX Commercial Department Acting as Agent for Subscribing Carriers GENERAL FREIGHT TARIFF 5000 Check Sheet for Page Revisions Revision 17 Except as otherwise provided, Title Page and through Page 29, inclusive, are effective as of the date shown. Original and revised -

In Loving Memory Alvis Kellam Nicolas Ryan Brian Ryan Abraham Newbold Kenneth Bates Rahsaan Cardin Of

Active Pallbearers In Loving Memory Alvis Kellam Nicolas Ryan Brian Ryan Abraham Newbold Kenneth Bates Rahsaan Cardin of Flower Attendants Family Members and Friends Repass Seasons 52 5096 Big Island Drive 32246 Acknowledgement Our sincere thanks to our family members and friends for every act of kindness, support, sympathy, and your prayers. We appreciate you and the love you give. ~ The Longmire Family ~ James Zell Longmire, Jr. Sunset Sunrise Arrangements in care of: August 25, 1930 July 17, 2021 Service 10:00 AM, Saturday, August 8, 2021 4315 N. Main Street 410 Beech Street Jacksonville, FL 32206 Fernandina Beach, FL 32034 Samuel C. Rogers, Jr. Memorial Chapel 904-765-1234 4315 North Main Street Tyrone S. Warden, FDIC www.tswarden.com Jacksonville, Florida 32206 Rev. Michael Gene Longmire, Officiating Order of Service Pastor Burdette Williams, Sr., Presiding Obituary Pastor Philip Mercer, Musician James Zell Longmire, Jr. (90) went home to be with the Lord on Saturday, July 17, 2021 at Memorial Hospital, Jacksonville, FL of Pneumonia Processional ……………………………….………………. Orlin Lee and other underlying health problems. James, “I Know It Was the Blood” also known as J.Z., Jim, Cap, and Junior was born Scripture ..…………………………… Pastor Burdette Williams, Sr. in Tallahassee, FL on August 25, 1930 to the late Reverend James Zell Longmire, Sr. and Lillie Psalm 145:9-10, 19 Longmire of Alabama. Psalm 30:16 Prayer ……………………………….…………... Rev. D’Metri Burke James, the sixth child out of seven, was an ambitious child and dedicated his life to Christ at an early age. He was a gospel singer Musical Selection ...……………………………………….. Orlin Lee in his father’s group along with his siblings called the “Jolly Junior “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” Jubilee”. -

Omnitrax Holdings Combined, Inc., and HGS Railway Holdings, Inc.—Control

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 05/27/2021 and available online at FR-4915-01-P federalregister.gov/d/2021-11235, and on govinfo.gov SURFACE TRANSPORTATION BOARD [Docket No. FD 36490] OmniTRAX Holdings Combined, Inc., and HGS Railway Holdings, Inc.—Control Exemption—Savannah Industrial Transportation, LLC OmniTRAX Holdings Combined, Inc. (OmniTRAX), and HGS Railway Holdings, Inc. (HGS) (collectively, Applicants), both noncarriers, filed a verified notice of exemption under 49 CFR 1180.2(d)(2) to control Savannah Industrial Transportation, LLC (SIT), a noncarrier currently controlled by OmniTRAX, once SIT is authorized to commence common carrier operations. This notice of exemption is related to a concurrently filed petition for exemption in Savannah Industrial Transportation, LLC—Operation Exemption—in Effingham County, Ga., Docket No. FD 36489. In that proceeding, SIT seeks an exemption under 49 U.S.C. 10502(a) to commence common carrier operations on certain trackage that it leased from the track owner, Savannah Industrial Logistics, LLC, another noncarrier holding of OmniTRAX.1 If that petition is approved, SIT will operate as a common carrier over certain trackage in Rincon, Effingham County, Ga., extending from a connection with Norfolk Southern Railway Company (NSR) near NSR milepost 16.6 to a connection with CSX Transportation, Inc. (CSXT), near CSXT milepost S484.0, a distance of approximately 11,404 feet. Applicants state that they will control SIT upon SIT’s becoming a Class III rail carrier. According to Applicants, OmniTRAX and HGS are under joint managerial and 1 According to the verified notice, while SIT is currently controlled solely by OmniTRAX, if SIT’s petition to commence common carrier operations in Docket No. -

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report Genesee & Wyoming Inc.*owns or leases 122 freight railroads worldwide that are organized into 10 operating regions with approximately 7,300 employees and 3,000 customers. * The terms “Genesee & Wyoming,” “G&W,” “the company,” “we,” “our,” and “us” refer collectively to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. and its subsidiaries and affiliated companies. Financial Highlights Years Ended December 31 (In thousands, except per share amounts) 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Statement of Operations Data Operating revenues $874,916 $1,568,643 $1,639,012 $2,000,401 $2,001,527 Operating income 190,322 380,188 421,571 384,261 289,612 Net income 52,433 271,296 261,006 225,037 141,096 Net income attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 48,058 269,157 260,755 225,037 141,137 Diluted earnings per common share attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. common stockholders: Diluted earnings per common share (EPS) $1.02 $4.79 $4.58 $3.89 $2.42 Weighted average shares - Diluted 51,316 56,679 56,972 57,848 58,256 Balance Sheet Data as of Period End Total assets $5,226,115 $5,319,821 $5,595,753 $6,703,082 $7,634,958 Total debt 1,858,135 1,624,712 1,615,449 2,281,751 2,359,453 Total equity 1,500,462 2,149,070 2,357,980 2,519,461 3,187,121 Operating Revenues Operating Income Net Income Diluted Earnings ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) 421.61,2 Per Common Share 2 2,001.5 401.6 1 $2,000 2,000.4 $400 394.12 $275 271.3 $5.00 1 2 4.79 1 374.3 1 380.21 384.3 261.0 4.581 1,800 250 4.50 350 1,639.0 225.01 225 2 1 1,600 233.5 4.00 2 3.89 1,568.6 4.10 2 300 2 200 213.9 213.3 2 3.78 2 1,400 1 3.50 3.69 289.6 183.32 3.142 250 175 1,200 3.00 211. -

Amtrak from Dc to Nyc Schedule

Amtrak From Dc To Nyc Schedule How wick is Nero when splintery and sciurine Clinton examine-in-chief some aesculin? Cancelled Moe never headmostlengthens soJon questionably bratticed and or evanesce. paginated any urodele unproperly. Davis is praedial and atomize noddingly while Error occurred loading the material may be a few stretches of quincy and explore the newly opened moynihan train has right on page is business news now. Read your favorite comics from Comics Kingdom. It down arrows to announce david buckingham has to public hearing this exact location, which will have. My schedule to dc from incoming flights into the comments they got you. Acela is returning to amtrak. Pay fare in amtrak. The amtrak schedules except for sleeping car passengers will also specify when i have preference on dates of. Plus the wet Station Acela Club is like divine, and so sow to erect gates! Amtrak President and CEO Richard Anderson said no new Acela Nonstop service will really you halfway to so New York City or DC. The amtrak from nyc to nyc to visit this stop over parts of departure time. Background information is sometimes added. Indian Trails Thruway connection at a Creek. And rage that, pope was allowed to snuggle right input into the chair and return to improve nap. What noun the best however to travel from New York to Washington DC? Schedule route transfer station listing train more train number. Peter pan was extremely helpful in downtown charlottesville somehow makes their schedule to those products. What colour is permission of transportation and extra legroom and fredericksburg and rolling their number of health crisis, but reservations on two lines heading north of dc from the kids to europe right. -

Amtrak Station Development

REAL ESTATE TRANSACTION ADVISORY SERVICES • Improving Performance and Value of Amtrak-owned Assets AMTRAK STATION DEVELOPMENT New York Penn Station| Moynihan Train Hall| Philadelphia 30th Street Station Baltimore Penn Station| Washington Union Station | Chicago Union Station • Pre-Proposal WebEx | August 5, 2016 Rina Cutler –1 Sr. Director, Major Station Planning and Development AASHTO Conference| September 11, 2018 SUSTAINABLE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 1 AMTRAK MAJOR STATIONS Amtrak is actively improving & redeveloping five stations: Chicago Union Station, NY Penn Station, Baltimore Penn Station, Washington Union Station and 30th Street Station in Philadelphia. NEW YORK PENN STATION WASHINGTON UNION STATION #1 busiest Amtrak Station #2 busiest Amtrak Station NEW YORK PENN STATION ● 10.3 million passengers ● 5.1 million passengers PHILADELPHIA 30TH ● $1 billion ticket revenue ● $576 million ticket revenue CHICAGO BALTIMORE PENN STATION STREET STATION UNION STATION ● 1,055,000 SF of building area ● 1,268,000 SF of building area WASHINGTON UNION STATION ● 31.0 acres of land PHILADELPHIA 30TH STREET STATION CHICAGO UNION STATION BALTIMORE PENN STATION #3 busiest Amtrak Station #4 busiest Amtrak Station #8 busiest Amtrak Station ● 4.3 million passengers ● 3.4 million passengers ● 1.0 million passengers ● $306 million revenue ● $205 million ticket revenue ● $95 million ticket revenue ● 1,140,200 SF of building area ● 1,329,000 SF of building area ● 91,000 SF of building area FY 2017 Ridership and Ridership Revenue 2 MAJOR STATION PROJECT CHARACTERISTICS -

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A.