Preschool Children and the 5-String Kantele: an Exercise in Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythological Archetypes in the Legendarium of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K

Mythological archetypes in the Legendarium of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series Anu Vehkomäki Master’s thesis English Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Autumn 2020 Table of contents Abstract 1. Introduction ………………………….………………………………… 4 2. Materials used ………………………………………...……………….. 6 3. Theory and Methodology …………………………………….……….. 8 3.1. Critique of Jung’s Theory…………………………………………….. 9 3.2. Terminology…………….…………………………………………….. 13 3.2.1. Myth, Mythology and Fairy Tale ………………………………… 13 3.2.2. Religion and Mythology in Tolkien’s Works …………………….. 14 4. Mythical Archetypes in Tolkien’s Works ……………………………... 17 4.1. Wise Men ……………………………………………………………... 17 4.2. Tricksters …..…………………………………………………………. 20 4.3. Heroes ………………………………………………………………… 24 4.4. Evil ……………………………………………………………………. 30 4.5. Mother ………………………………………………………………… 38 4.6. Shadow ………………………………………………………………… 43 5. Mythological Archetypes in Harry Potter Series ………………………. 49 5.1. Wise Men ……………………………………………………………… 49 5.2. Tricksters.……………………………………………………………… 51 5.3. Heroes …………………………………………………………………. 54 5.4. Evil ……………………………………………………………………. 56 5.5. Mother ………………………………………………………………… 57 6. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………... 64 Works cited 2 Abstract This thesis introduces mythical archetypes in J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling’s works. Tolkien’s legendarium is filled with various elements from other mythologies and if read side by side many points in which these myths cross with paths with his creations can be found. In this thesis Tolkien’s works represent the literary myth. Rowling’s Harry Potter series is a fantasy series targeted to children without the same level of mythology attached. High fantasy represented by Tolkien is known for being myth like in its nature. Tolkien has stated in Letter 131 that he wanted to create a mythology for England and knowingly borrowed elements from world’s mythologies and adapted them to his own writing. -

Finnish Studies

Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 23 Number 1 November 2019 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-7328298-1-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458, Box 2146, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hilary-Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Tim Frandy, Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University Daniel Grimley, Professor, Oxford University Titus Hjelm, Associate Professor, University of Helsinki Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Johanna Laakso, Professor, University of Vienna Jason Lavery, Professor, Oklahoma State University James P. Leary, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, University of Helsinki Jussi Nuorteva, Director General, The National Archives of Finland Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury Beth L. -

Finnish Literature Society

Folklore Fellows’ NETWORK No. 1 | 2018 www.folklorefellows.fi • www.folklorefellows.fi • www.folklorefellows.fi Folklore Fellows’ NETWORK No. 1 | 2018 FF Network is a newsletter, published twice a year, related to Contents FF Communications. It provides information on new FFC volumes and on articles related to cultural studies by internationally recognised authors. The Two Faces of Nationalism 3 Pekka Hakamies Publisher Fin nish Academy of Science An Update to the Folklore Fellows’ Network and Letters, Helsinki Bulletin 4 Petja Kauppi Editor Pekka Hakamies [email protected] National Identity and Folklore: the Case of Ireland 5 Mícheál Briody Editorial secretary Petja Kauppi [email protected] Folk and Nation in Estonian Folkloristics 15 Liina Saarlo Linguistic editor Clive Tolley Finnish Literature Society (SKS) Archives 26 Editorial office Risto Blomster, Outi Hupaniittu, Marja-Leena Jalava, Katri Kalevala Institute, University of Turku Kivilaakso, Juha Nirkko, Maiju Putkonen & Jukka Saarinen Address Kalevala Institute, University of Turku Latest FFC Publications 31 20014 Turku, Finland FFC 313: Latvian Folkloristics in the Interwar Period. Ed. Dace Bula. FFC 314: Matthias Egeler, Atlantic Outlooks on Being at Home. Folklore Fellows on the internet www.folklorefellows.fi ISSN-L 0789-0249 ISSN 0789-0249 (Print) ISSN 1798-3029 (Online) Subscriptions Cover: Student of Estonian philology, Anita Riis (1927−1995) is standing at the supposed-to-be www.folklorefellows.fi Kalevipoeg’s boulder in Porkuni, northern Estonia in 1951. (Photo by Ülo Tedre. EKM KKI, Foto 1045) Editorial The Two Faces of Nationalism Pekka Hakamies his year many European nations celebrate their centenaries; this is not mere chance. The First World War destroyed, on top of everything else, many old regimes where peoples that had T lived as minorities had for some time been striving for the right to national self-determina- tion. -

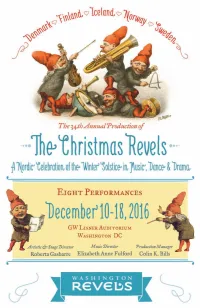

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles. -

Design and Analysis of a Modified Kantele with Increased Loudness

ACTA ACUSTICA UNITED WITH ACUSTICA Vol. 91 (2005) 261 – 268 Design and Analysis of a Modified Kantele with Increased Loudness Henri Penttinen , Cumhur Erkut , Jyrki P¨olkki , Vesa V¨alim¨aki , Matti Karjalainen : Helsinki University of Technology, Laboratory of Acoustics and Audio Signal Processing, P.O. Box 3000, FI-02015 HUT, Espoo, Finland. Henri.Penttinen@tkk.fi : Soitinrakentajat AMF, Tuikkalantie 2, 79100 Lepp¨avirta, Finland. jyrki.polkki@estelle.fi Summary The kantele, an ancient plucked string instrument, belongs to the family of zithers, and it is still used in tradi- tional folk music in Finland, Northwest Russia, and the Baltic countries. Design rules for making the kantele louder are proposed and confirming analysis results are presented. A description of the main characteristics of the traditional design of the kantele is given, so that it supports the presentation of the design rules and analysis results. The design rules to make a plucked string instrument louder are (I) increase the string tension, (II) in- crease the radiation surface, and (III) isolate the top plate from the sound-box with an air gap. Rules (I) and (II) are almost self evident, for musical acousticians. Rule (III) on the other hand is more unique, since it enables a freely vibrating top plate. The design rules are confirmed by comparing the traditional design with the new one, through several methodological aspects. Results from the analysis are drawn from both analytical treatments and acoustical measurements. The effect that the new design has on the instrument’s dynamic range and perception is investigated through a playability test with several professional kantele players. -

Nodes of Contemporary Finnish Literature

Nodes of Contemporary Finnish Literature Edited by Leena Kirstinä Studia Fennica Litteraria The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Markku Haakana, professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Timo Kaartinen, professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Kimmo Rentola, professor, University of Turku, Finland Riikka Rossi, docent, University of Helsinki, Finland Hanna Snellman, professor, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Lotte Tarkka, professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen, Secretary General, Dr. Phil., Finnish Literature Society, Finland Pauliina Rihto, secretary of the board, M. A., Finnish Literary Society, Finland Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Nodes of Contemporary Finnish Literature Edited by Leena Kirstinä Finnish Literature Society • Helsinki Studia Fennica Litteraria 6 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2012 Leena Kirstinä and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2012 by the Finnish Literature Society. -

The Finnish Five-String Kantele: Sustainably Designed for Musical Joy

DOI: 10.2478/jtes-2014-0004 Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 76ñ88, 2014 The Finnish Five-String Kantele: Sustainably Designed for Musical Joy Inkeri Ruokonen, Anu Sepp, Venla Moilanen, Ossi Autio and Heikki Ruism‰ki University of Helsinki, Finland Abstract This article discusses the five-string kantele as an example of the Finnish national heritage, a school instrument and an example of sustainable design. A qualitative case study was made by collecting the data from the Finnish students ñ prospective teachers ñ and the sixth form pupils, who had designed and carved their own five-string kanteles. The purpose of this research was to find out which aspects of five-string kantele design are considered the most important for sustainable principles and design among these youngsters. As results, the elements and principles of designing the five-string kantele are discussed and its relevance to five sustainable characteristics (creative, ecological, economic, aesthetic and socio-environmental) is presented. The sustainable values of the kantele and the purpose for which it is made are also considered. Keywords: sustainable design, artifact, five-string kantele, musical instrument design, the Kalevala Introduction This paper discusses the five-string kantele as an example of sustainable design. The theoretical background discusses the role of the five-string kantele in the Kalevala and the cultural-ideological information that is conveyed through its use and construction. The principles and values of sustainable design are presented as well as contemporary design and research on the Finnish five-string kantele. The five-string kantele is an example of the Finnish national heritage, a heritage that has become a part of Finlandís living musical culture in kindergartens and schools. -

Novels, Histories, Novel Nations Historical Fiction and Cultural Memory in Finland and Estonia

Novels, Histories, Novel Nations Historical Fiction and Cultural Memory in Finland and Estonia Edited by Linda Kaljundi, Eneken Laanes and Ilona Pikkanen Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Pasi Ihalainen, Professor, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Timo Kaartinen, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Taru Nordlund, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Riikka Rossi, Title of Docent, Researcher, University of Helsinki, Finland Katriina Siivonen, Sunstitute Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Lotte Tarkka, Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen, Secretary General, Dr. Phil., Finnish Literature Society, Finland Tero Norkola, Publishing Director, Finnish Literature Society, Finland Maija Hakala, Secretary of the Board, Finnish Literature Society, Finland Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Novels, Histories, Novel Nations Historical Fiction and Cultural Memory in Finland and Estonia Edited by Linda Kaljundi, Eneken Laanes & Ilona Pikkanen Finnish Literature Society SKS • Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 19 The publication has undergone a peer review. -

Kanteleen Ohjelmistoluettelo a Ja B Ja C Ja Dpdf

KANTELEENSOITTO A - LUETTELO 1 (3gs2) Osasto 1 Sooloteoksia Albeniz, I. Torre Bermeja Armfelt, C. Shimmering Steps Bach, J. S. Suite BWV 1006 a Suite BWV 995 Bashmakov, L. Kuusi etydiä kanteleelle (sarjana) Bashmakov, L. Heija Büsser, H. Prelude et Danse van Delden, L. Impromptu Freeman, A. Magnolia Grandjany, M. Fantaisie op. 31 sur un théme de Haydn Hamel, P. M. Miniaturen für harfe Hyvärinen, A. Valse griffyre Jalkanen, P. Toccata Pro Terva (15-kieliselle kanteleelle) Jõeleht, L. Consolator Larchikov, V. Canto doloroso (10-kieliselle ja konserttikanteleelle, yksi soittaja) Linkola, J. Kolme karaktääriä Summer tales (A Suite for Kantele with optional Percussion) Livorsi, P. Ascolta Länsiö, T. Merry Picker Marcland, P. Stretto Minami, S. Solo Pierné, G. Impromptu-Caprice op.9 Rak, S. Spectrum (sarjana) Ropartz, G. Impromptu Roussell, A. Impromptu op. 21 Saint-Saëns, C. Fantaisie op. 95 Sallinen, W. Reema Scarlatti, D. Sonata in F, K. 469 Sumera, L. Piece from the Year 1981 Trjobevic´, J. Lento Tuomela. T. Kuura Valpola, H. Kantona Virtaperko, O. Vaeltaja 32 (teoksen 1. osaa ”Ahkera kulkija” voidaan soittaa myös itsenäisenä teoksena) Whittall, M. The Wine-Dark Sea II Yokoyama, M. Awai e Osasto 2 Laajamuotoisia teoksia Almila, A. Sinisonatiini Hämeenniemi, E. Randzani Jalkanen, P. Vecernie Kostiainen, P. Contemplations for kantele Linjama, J. Johdanto, muunnelmia ja kehtolaulu Nevanlinna, T. Soimisesta Nieminen, K. Tarantula Nuorvala, J. Kolme kappaletta puhdasvireiselle sähkökanteleelle Suilamo, H. Unohduksen pisara - rukousnauhasonaatteja konserttikanteleelle Tiensuu, J. Manaus Aavesonaatti konserttikanteleelle Viotti, J. B. Sonate pour la harpe Osasto 3 Konserttoja Gudmundsson, H. Alkul – A Concerto for Kantele and String Orchestra Jalkanen, P Konsertto kanteleelle ja jousiorkesterille Nordgren, P.H. -

Finnish Studies

JOURNAL OF INNISH TUDIES F S From Cultural Knowledge to Cultural Heritage: Finnish Archives and Their Reflections of the People Guest Editors Pia Olsson and Eija Stark Theme Issue of the Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 18 Number 1 October 2014 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-96-1 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1402; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University; hilary.virtanen@finlandia. edu Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Richard Impola, Professor Emeritus, New Paltz, New York Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of Finnish Literature, University of Helsinki Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, Institute for Northern Culture, University of Lapland Douglas Robinson, Professor, Dean, Hong Kong Baptist University Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury George Schoolfield, Professor Emeritus, Yale University Beth L. -

Finnish Studies

JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES Volume 16 Number 2 May 2013 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1402; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Associate Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Assistant Editor, University of Wisconsin; [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University, Toronto Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University, New York Anselm Hollo, Professor, Naropa Institute, Boulder, Colorado Richard Impola, Professor Emeritus, New Paltz, New York Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of -

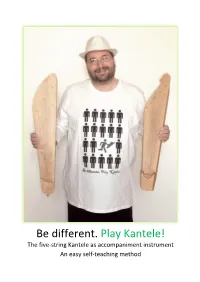

Be Different. Play Kantele! the Five-String Kantele As Accompaniment Instrument an Easy Self-Teaching Method

Be different. Play Kantele! The five-string Kantele as accompaniment instrument An easy self-teaching method Be different. Play Kantele! 1. Introduction 2. A (very brief) history of the kantele 3. Parts of the kantele 4. Where can I get a kantele? 5. What else do I need to get started? 6. Tuning the five-string kantele 7. How to hold your kantele 8. The first chord: D-major 9. More chords: G, A and A7 10. The right hand: Strumming 11. Some minor chords: Bm, Em, F#m 12. More chords: C, Am, Dm, E7, Asus4, Dsus2, Dsus4 13. Transposing other keys to D-major 14. Variation: D-minor tuning 15. More songs from Finland 16. Chord charts 17. Epilogue 18. Index 1 1. Introduction The kantele is a musical instrument with a long tradition in Finland and Karelia. In former times there used to be a kantele in almost every Finnish house. Usually it was carved out of one single piece of wood. As a foreigner, I am not familiar with old Finnish folk songs or the old "runes" of the Kalevala. Most of the time, I play the kantele in chord style. That is big fun! You can learn to play the kantele at any age. Have you never played a musical instrument before? Have you been told that you are not musically talented? Give the kantele a try! The five-string kantele is an easy-to-learn instrument. You can take it wherever you go. Whenever you like to sing with your own family, or if you work with children or elderly people in your job or as a volunteer – take a kantele in your hands to support or accompany your singing! With this book you can learn the first chords.