The Might of Word and Song by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visits to Tuonela Ne of the Many Mythologies Which Have Had an In

ne of the many mythologies which have had an in fluence on Tolkien's work was the Kalevala, the 22000- line poem recounting the adventures of a group of Fin nish heroes. It has many characteristics peculiar to itself and is quite different from, for example, Greek or Germanic mythology. It would take too long to dis cuss this difference, but the prominent role of women (particularly mothers) throughout the book may be no ted, as well as the fact that the heroes and the style are 'low-brow', as Tolkien described them, as opposed to the 'high-brow' heroes common in other mytholog- les visits to Tuonela (Hades) are fairly frequent; and magic and shape-change- ing play a large part in the epic. Another notable feature which the Kaleva la shares with QS is that it is a collection of separate, but interrelated, tales of heroes, with the central theme of war against Pohjola, the dreary North, running through the whole epic, and individual themes in the separate tales. However, it must be appreciated that QS, despite the many influences clearly traceable behind it, is, as Carpenter reminds us, essentially origin al; influences are subtle, and often similar incidents may occur in both books, but be employed in different circumstances, or be used in QS simply as a ba sis for a tale which Tolkien would elaborate on and change. Ibis is notice able even in the tale of Turin (based on the tale of Kullervo), in which the Finnish influence is strongest. I will give a brief synopsis of the Kullervo tale, to show that although Tolkien used the story, he varied it, added to it, changed its style (which cannot really be appreciated without reading the or iginal ), and moulded it to his own use. -

Mythological Archetypes in the Legendarium of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K

Mythological archetypes in the Legendarium of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series Anu Vehkomäki Master’s thesis English Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Autumn 2020 Table of contents Abstract 1. Introduction ………………………….………………………………… 4 2. Materials used ………………………………………...……………….. 6 3. Theory and Methodology …………………………………….……….. 8 3.1. Critique of Jung’s Theory…………………………………………….. 9 3.2. Terminology…………….…………………………………………….. 13 3.2.1. Myth, Mythology and Fairy Tale ………………………………… 13 3.2.2. Religion and Mythology in Tolkien’s Works …………………….. 14 4. Mythical Archetypes in Tolkien’s Works ……………………………... 17 4.1. Wise Men ……………………………………………………………... 17 4.2. Tricksters …..…………………………………………………………. 20 4.3. Heroes ………………………………………………………………… 24 4.4. Evil ……………………………………………………………………. 30 4.5. Mother ………………………………………………………………… 38 4.6. Shadow ………………………………………………………………… 43 5. Mythological Archetypes in Harry Potter Series ………………………. 49 5.1. Wise Men ……………………………………………………………… 49 5.2. Tricksters.……………………………………………………………… 51 5.3. Heroes …………………………………………………………………. 54 5.4. Evil ……………………………………………………………………. 56 5.5. Mother ………………………………………………………………… 57 6. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………... 64 Works cited 2 Abstract This thesis introduces mythical archetypes in J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling’s works. Tolkien’s legendarium is filled with various elements from other mythologies and if read side by side many points in which these myths cross with paths with his creations can be found. In this thesis Tolkien’s works represent the literary myth. Rowling’s Harry Potter series is a fantasy series targeted to children without the same level of mythology attached. High fantasy represented by Tolkien is known for being myth like in its nature. Tolkien has stated in Letter 131 that he wanted to create a mythology for England and knowingly borrowed elements from world’s mythologies and adapted them to his own writing. -

Finnish Studies

Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 23 Number 1 November 2019 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-7328298-1-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458, Box 2146, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hilary-Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Tim Frandy, Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University Daniel Grimley, Professor, Oxford University Titus Hjelm, Associate Professor, University of Helsinki Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Johanna Laakso, Professor, University of Vienna Jason Lavery, Professor, Oklahoma State University James P. Leary, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, University of Helsinki Jussi Nuorteva, Director General, The National Archives of Finland Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury Beth L. -

The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot's Kalevala

Oral Tradition, 8/2 (1993): 247-288 From Maria to Marjatta: The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala1 Thomas DuBois The question of Elias Lönnrot’s role in shaping the texts that became his Kalevala has stirred such frequent and vehement debate in international folkloristic circles that even persons with only a passing interest in the subject of Finnish folklore have been drawn to the question. Perhaps the notion of academic fraud in particular intrigues those of us engaged in the profession of scholarship.2 And although anyone who studies Lönnrot’s life and endeavors will discover a man of utmost integrity, it remains difficult to reconcile the extensiveness of Lönnrot’s textual emendations with his stated desire to recover and present the ancient epic traditions of the Finnish people. In part, the enormity of Lönnrot’s project contributes to the failure of scholars writing for an international audience to pursue any analysis beyond broad generalizations about the author’s methods of compilation, 1 Research for this study was funded in part by a grant from the Graduate School Research Fund of the University of Washington, Seattle. 2 Comparetti (1898) made it clear in this early study of Finnish folk poetry that the Kalevala bore only partial resemblance to its source poems, a fact that had become widely acknowledged within Finnish folkoristic circles by that time. The nationalist interests of Lönnrot were examined by a number of international scholars during the following century, although Lönnrot’s fairly conservative views on Finnish nationalism became equated at times with the more strident tone of the turn of the century, when the Kalevala was made an inspiration and catalyst for political change (Mead 1962; Wilson 1976; Cocchiara 1981:268-70; Turunen 1982). -

Finnish Literature Society

Folklore Fellows’ NETWORK No. 1 | 2018 www.folklorefellows.fi • www.folklorefellows.fi • www.folklorefellows.fi Folklore Fellows’ NETWORK No. 1 | 2018 FF Network is a newsletter, published twice a year, related to Contents FF Communications. It provides information on new FFC volumes and on articles related to cultural studies by internationally recognised authors. The Two Faces of Nationalism 3 Pekka Hakamies Publisher Fin nish Academy of Science An Update to the Folklore Fellows’ Network and Letters, Helsinki Bulletin 4 Petja Kauppi Editor Pekka Hakamies [email protected] National Identity and Folklore: the Case of Ireland 5 Mícheál Briody Editorial secretary Petja Kauppi [email protected] Folk and Nation in Estonian Folkloristics 15 Liina Saarlo Linguistic editor Clive Tolley Finnish Literature Society (SKS) Archives 26 Editorial office Risto Blomster, Outi Hupaniittu, Marja-Leena Jalava, Katri Kalevala Institute, University of Turku Kivilaakso, Juha Nirkko, Maiju Putkonen & Jukka Saarinen Address Kalevala Institute, University of Turku Latest FFC Publications 31 20014 Turku, Finland FFC 313: Latvian Folkloristics in the Interwar Period. Ed. Dace Bula. FFC 314: Matthias Egeler, Atlantic Outlooks on Being at Home. Folklore Fellows on the internet www.folklorefellows.fi ISSN-L 0789-0249 ISSN 0789-0249 (Print) ISSN 1798-3029 (Online) Subscriptions Cover: Student of Estonian philology, Anita Riis (1927−1995) is standing at the supposed-to-be www.folklorefellows.fi Kalevipoeg’s boulder in Porkuni, northern Estonia in 1951. (Photo by Ülo Tedre. EKM KKI, Foto 1045) Editorial The Two Faces of Nationalism Pekka Hakamies his year many European nations celebrate their centenaries; this is not mere chance. The First World War destroyed, on top of everything else, many old regimes where peoples that had T lived as minorities had for some time been striving for the right to national self-determina- tion. -

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles. -

The Role of the Kalevala in Finnish Culture and Politics URPO VENTO Finnish Literature Society, Finland

Nordic Journal of African Studies 1(2): 82–93 (1992) The Role of the Kalevala in Finnish Culture and Politics URPO VENTO Finnish Literature Society, Finland The question has frequently been asked: would Finland exist as a nation state without Lönnrot's Kalevala? There is no need to answer this, but perhaps we may assume that sooner or later someone would have written the books which would have formed the necessary building material for the national identity of the Finns. During the mid 1980s, when the 150th anniversary of the Kalevala was being celebrated in Finland, several international seminars were held and thousands of pages of research and articles were published. At that time some studies appeared in which the birth of the nation state was examined from a pan-European perspective. SMALL NATION STATES "The nation state - an independent political unit whose people share a common language and believe they have a common cultural heritage - is essentially a nineteenth-century invention, based on eighteenth-century philosophy, and which became a reality for the most part in either the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. The circumstances in which this process took place were for the most part marked by the decline of great empires whose centralised sources of power and antiquated methods of administrations prevented an effective response to economic and social change, and better education, with all the aspirations for freedom of thought and political action that accompany such changes." Thus said Professor Michael Branch (University of London) at a conference on the literatures of the Uralic peoples held in Finland in the summer of 1991. -

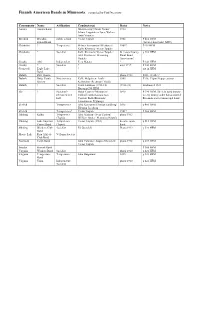

Finnish American Bands in Minnesota, Compiled by Paul Niemisto

Finnish American Bands in Minnesota, compiled by Paul Niemisto Community Name Affiliation Conductor(s) Dates Notes Aurora Aurora Band Miettinen(sp?)/Matti Niemi/ 1910 Jalmar Laupiainen/ Isaac Walma/ Antti Viitanen. Biwabik Biwabik public school Victor Taipale 1902 P 482 HFM School Band (1st in school band MN?) Chisholm ? Temperence Helmer hermanson/ Miettunen/ 1904? P494 HFM Kalle Kleimola/ Victor Taipale Chisholm ? Socialist Kalle Kleimola/ Victor Taipale/ St Louis County p 498 HFM Alex Koivunen/ Hemming Rural Band Hautala Association? Crosby Ahti Independent Eero Matara ? P 141 HFM Crosby ? Socialist ? after 1917 P 141 HFM Cromwell Eagle Lake ? not in HFM Band Duluth SSO Osasto photo 1913 P243, cl+trb+7 Duluth Nuija Youth Nuorisoseura Kalle Holpainen/ Louhi/ 1905 P246, Viipuri/Lappeenranta Society Kellosalmi/ Beckman/ Yrjölä Duluth ? Socialist Frank Lindroos (1913-18) (1913-18) Lindroos d 1923 Bio on p 298 HFM Ely ? Socialist?- Oskar Castren/ Miettunen/ 1890 P 390 HFM, The Ely band history rehearsed in S Farihoff/ Erkki Laitala/Jack is very murky/ other bands started/ hall Castren/ Kalle Kleimola/ Kleemols started municipal band Liimatainen/ Pyylampi Eveleth Termperence Alex Koivunen/ Herman Lindberg/ 1895 p 466 HFM Filemon Jacobson Eveleth Termperence? Victor Taipale 1901? P 466 HFM Hibbing Kaiku Temperence Alex Mattson/ Oscar Castren/ photo 1913 (Tapio) William Ahola/ Hemming Hautala Hibbing Lake Superior Temperence Victor Taipale (1901) became town p 512 HFM Cornet Band (Tapio) band Hibbing Workers Club Socialist Ed Grondahl Photo 1912 p 521 HFM Band Moose Lake Raju Athletic Vellamo Society Club Band Naswauk Town Band John Colander/ August Miettinen/ photo 1912 p 607 HFM Victor Taipale Soudan Finnish Band P 366 HFM Virginia Workers Band Socialist photo 1910 p 421 HFM Virginia Temperance Temperance John Haapasaari 1895 p 422 HFM Band Virginia Yrinä Independent/ photo 1910 p 422 HFM Socialist . -

Hist Lab Esitelmä Ljubljana 10

Sari Saresto, Helsinki City Museum A presentation in Ljubljana, AN hist lab, 10th March 2006 Pohjola Insurance Building (1899-1901) International concepts are conveyed as a synthesis of national motifs and genuine materials In search of national identity: Finland was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1809. Russia wished to sever Finland’s close ties with former mother country Sweden and thus designated Helsinki as the capital of the Grand Duchy. Under Swedish rule, Turku had been the seat of government and higher education. Helsinki was geographically closer to Russia than the west coast city of Turku, (which almost seemed to gravitate towards Sweden), and thus also more easily supervised from St Petersburg. The Grand Duchy was allowed to retain its laws dating back to the time of Swedish rule. The language of government was Swedish, which was only spoken by 5% of the nation’s population. In Helsinki, however, nearly the entire population was Swedish-speaking. Nor was Swedish the language only of the upper echelons of society; it was spoken even by menial labourers. It wasn’t until the 1860s and the 1870s that the proportion of Finnish-speakers began to rapidly climb in Helsinki. The exhortation of “Swedes we are no longer, Russians we can never become, so let us be Finns” was first heard back in the 1820s. Finnish was the language of the people and its status was only highlighted by the Kalevala, the national epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot and published for the first time in 1835. This epic poem told, in Finnish, the tale of the world from its creation, speaking of an ancient, mystical past replete with legendary heroes, tribal wars, witches and magical devices. -

Program Notes November 9, 2019 Wagnerian Music Dramas

Program Notes November 9, 2019 Wagnerian music dramas. Sibelius soured on Wagner’s The Swan of Tuonela from Four Legends compositional methods soon thereafter, and The Swan from the Kalevala, Op. 22 of Tuonela was published with three other short symphonic poems as the suite Four Legends from JEAN SIBELIUS (1965 - 1957) the Kalevala, Op. 22. Each of the four works depicts an adventure from the life of the mythic Finnish hero As Jean Sibelius came to maturity as man and Lemminkäinen, the central figure of the Kalevala, musician, his country lived under the growing A the national epic of Finland. threat of absorption into the Russian Empire. Finland Sibelius inscribed the following words on the score: had been a Grand Duchy of Russia since 1809, but “Tuonela, the land of death, the hell of it enjoyed a great degree of autonomous freedom, Finnish mythology, is surrounded by a with its own parliament and court system. Starting large river of black waters and a rapid during the reign of Czar Alexander III and continuing current, in which The Swan of Tuonela with Nicolas II, Russia began to limit the rights of glides majestically, singing.“ Finns, curtailing the authority of parliament, mandating Sibelius scores the work for solo English horn, military service and eventually dissolving the oboe, bass clarinet, two bassoons, four horns, three Finnish army. trombones, timpani, bass drum, harp and muted Rather than taking up arms, the Finns fought back strings – an ensemble of dark orchestral colors suitable with their culture against the encroachment on their for depicting the desolation of Tuonela. -

Semantics of Wainamoinen's Proper Names in Kalevala

Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana ISSN: 1315-5216 ISSN: 2477-9555 [email protected] Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Semantics of Wainamoinen’s Proper Names in Kalevala BULINA, Evgeniya Nicolaevna; SOLNYSHKINA, Marina Ivanovna; BAHTIOZINA, Marina Georgievna Semantics of Wainamoinen’s Proper Names in Kalevala Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, vol. 25, no. Esp.7, 2020 Universidad del Zulia, Venezuela Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27964362050 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4009780 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, 2020, vol. 25, no. Esp.7, Septiembre, ISSN: 1315-5216 2477-9555 Artículos Semantics of Wainamoinen’s Proper Names in Kalevala Semántica de los nombres propios de Wainamoinen en Kalevala Evgeniya Nicolaevna BULINA DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4009780 Kazan Federal University., Rusia Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? [email protected] id=27964362050 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0296-815X Marina Ivanovna SOLNYSHKINA Kazan Federal University., Rusia [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1885-3039 Marina Georgievna BAHTIOZINA Moscow State University, Rusia [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4376-3553 Received: 03 August 2020 Accepted: 07 September 2020 Abstract: e article presents semantic analysis of proper names of Wainamoinen, one of the major characters of the Finnish epos Kalevala. e comparative analysis revealed the following layers of information in Wainamoinen’s proper names: a transparent inner form of names (Väinämäinen / Wainamoinen, Väinö / Waino, Suvantolainen / Suwantolainen, Uvantolaynen, Osmoynen, Kalevainen, Kalevalainen) of finnish origin, language and lack of transparency of Wainamoinen’s names in English, an additional connotation formed by the morphological structures of the names and a social status, dependent on the relationship of the addresser and the addressee. -

A History of Toivola, Michigan by Cynthia Beaudette AALC

A A Karelian Christmas (play) A Place of Hope: A History of Toivola, Michigan By Cynthia Beaudette AALC- Stony Lake Camp, Minnesota AALC- Summer Camps Aalto, Alvar Aapinen, Suomi: College Reference Accordions in the Cutover (field recording album) Adventure Mining Company, Greenland, MI Aged, The Over 80s Aging Ahla, Mervi Aho genealogy Aho, Eric (artist) Aho, Ilma Ruth Aho, Kalevi, composers Aho, William R. Ahola, genealogy Ahola, Sylvester Ahonen Carriage Works (Sue Ahonen), Makinen, Minn. Ahonen Lumber Co., Ironwood, Michigan Ahonen, Derek (playwrite) Ahonen, Tauno Ahtila, Eija- Liisa (filmmaker) Ahtisaan, Martti (politician) Ahtisarri (President of Finland 1994) Ahvenainen, Veikko (Accordionist) AlA- Hiiro, Juho Wallfried (pilot) Ala genealogy Alabama Finns Aland Island, Finland Alanen, Arnold Alanko genealogy Alaska Alatalo genealogy Alava, Eric J. Alcoholism Alku Finnish Home Building Association, New York, N.Y. Allan Line Alston, Michigan Alston-Brighton, Massachusetts Altonen and Bucci Letters Altonen, Chuck Amasa, Michigan American Association for State and Local History, Nashville, TN American Finn Visit American Finnish Tourist Club, Inc. American Flag made by a Finn American Legion, Alfredo Erickson Post No. 186 American Lutheran Publicity Bureau American Pine, Muonio, Finland American Quaker Workers American-Scandinavian Foundation Amerikan Pojat (Finnish Immigrant Brass Band) Amerikan Suomalainen- Muistelee Merikoskea Amerikan Suometar Amerikan Uutiset Amish Ammala genealogy Anderson , John R. genealogy Anderson genealogy