Possibilities of Lyric: Reading Petrarch in Dialogue. with An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gli Immediati Dintorni Franco Arminio

Gli immediati dintorni La bellezza Incontro con lo scrittore, poeta e “paesologo” Franco Arminio Portami con te in un supermercato, dentro un bar, nel parcheggio di un ospedale. Spezza con un bacio il filo a cui sto appeso. Portami con te in una strada di campagna, dove abbaiano i cani, vicino a un’officina meccanica, dentro a una profumeria. Portami dove c’è il mondo, non dove c’è la poesia. (da Cedi la strada agli alberi, Chiarelettere, 2017) L’autore sarà presentato da Fabio Pusterla. Martedì 17 ottobre 2017 ore 18.00 Aula magna del Liceo cantonale di Lugano 1 viale Carlo Cattaneo 4 – Lugano Franco Arminio (1960) è un poeta, scrittore e regista italiano, fondatore della disciplina da lui definita “paesologia”. Molto apprezzato da Roberto Saviano, Arminio ha pubblicato, tra le altre opere, Vento forte tra Lacedonia e Candela. Esercizi di paesologia (Laterza 2008, Premio Napoli); Cartoline dai morti (Nottetempo 2010, Premio Stephen Dedalus); Terracarne (Mondadori 2011, Premi Carlo Levi e Volponi); Geografia commossa dell’Italia interna (Bruno Mondadori 2013) e i libri di poesia Poeta con famiglia (Edizioni d’If 2009), Stato in luogo (Transeuropa 2012) e il fortunatissimo Cedi la strada agli alberi (Chiarelettere 2017). È animatore del blog “Comunità provvisorie” e direttore artistico del festival di paesologia “La luna e i calanchi”. Celle qui ruine l’être, la beauté, sera suppliciée, mise à la roue, déshonorée, dite coupable, faite sang (…) Notre haut désespoir sera que tu vives, notre coeur que tu souffres, notre voix de t’humilier parmis tes larmes, de te dire la menteuse, la pourvoyeuse du ciel noir, notre désire pourtant étant ton corps infirme, notre pitié ce coeur menant à toute boue. -

5. Numeri Di Letterature

I PRIMI 9 ANNI DI LETTERATURE Festival Internazionale di Roma Nelle prime 9 EDIZIONI di Letterature Festival Internazionale di Roma, la Basilica di Massenzio ha ospitato 300.000 SPETTATORI in 91 SERATE . 183 SCRITTORI e POETI , accompagnati da 88 ATTORI , 123 MUSICISTI o GRUPPI e 14 VIDEO ARTISTI , sono saliti sul palco e hanno letto 150 TESTI INEDITI scritti appositamente per le diverse edizioni del Festival e poi raccolti in 9 CATALOGHI. Durante il periodo del festival nei 9 ANNI di programmazione oltre 200.000 PERSONE hanno visitato il sito www.festivaldelleletterature.it dove è possibile rileggere i testi inediti e avere maggiori informazioni su autori e artisti partecipanti. Dallo scorso anno, inoltre, il Festival è sbarcato sui social network: è stato creato il canale FLICKR che al momento raccoglie 279 FOTO , il canale youtube con 49 VIDEO , la pagina FACEBOOK e la pagina TWITTER. 2002 | SOLI, INSIEME Una riflessione sul rapporto tra la memoria del vissuto individuale e di quello collettivo. Michael Chabon, Jonathan Coe, Jostein Gaarder, Günter Grass, David Grossman, J.T. Leroy, Frank McCourt, Ian McEwan, Patrick McGrath, Toni Morrison, Amélie Nothomb, Luis Sepúlveda, Manuel Vázquez Montálban, Derek Walcott, Abraham B. Yehoshua. 2003 | PASSATO, FUTURO Una riflessione sul rapporto tra l’esperienza del passato e le brucianti questioni del domani Doris Lessing, Jonathan Lethem, Jeffrey Eugenides, Andrea Camilleri, Boris Akunin, Alan Warner, Don DeLillo, Tracy Chevalier, Daniel Pennac, Susan Sontag, Alice Sebold, Irina Denezkina, Dacia Maraini, Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Hanif Kureishi, Paul Auster. 2004 | REALE, IMMAGINARIO Il vissuto e l’immaginazione, la realtà e la fantasia, la Letteratura ne fa oggetto costante di riflessione, propria “materia” di lavoro . -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 20 April 2012

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 20 April 2012 AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE CASA DELLE LETTERATURE DI ROMA CAPITALE ANNOUNCES A TWO-DAY SERIES OF READINGS AND CONVERSATIONS ABOUT TRANSLATING MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY POETRY ON 3 & 4 MAY 2012 Giorgio Vasari, Uomo che legge alla finestra, affresco Museo statale di Casa Vasari, sala del Trionfo e della Virtù Su concessione del Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali – Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici, Paesaggistici, Storici, Artistici ed Etnoantropologici di Arezzo “C’è più onore in tradire che in essere fedeli a metà” / “There is more honor in betrayal than in being half faithful” – Giovanni Giudici (1924-2011), from his poem “Una Sera Come Tante” / “An Evening Like So Many Others” Rome - The American Academy in Rome is pleased to present Translating Poetry: Readings and Conversations, a two-day event featuring a series of readings and conversations by international writers and translators that will explore the translation of modern and contemporary Polish and Italian poetry into English, as well as the translation of English-language poetry into Italian. The events will take place on Thursday 3 May at the Academy’s Villa Aurelia and on Friday 4 May at the Casa delle Letterature in the historic center of Rome. The sessions will be in English or Italian (Polish poetry will also be read in its original language) and simultaneous translations of public conversations (in English and Italian) will be available. Karl Kirchwey, poet and Andrew Heiskell Arts Director at the American Academy in Rome, said, “2011 at the AAR featured a major tribute to Nobel Laureate Joseph Brodsky, former Trustee of the Academy, and the world premiere performance of a new play by Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott. -

Italian (ITAL) 1

Italian (ITAL) 1 ITAL 2500. Approaches to Literature. (4 Credits) ITALIAN (ITAL) A basic course in Italian literature. Close readings in the major forms, prose fiction, poetry and drama, and an introduction to the varieties of ITAL 1001. Introduction to Italian I. (5 Credits) critical strategies for reading them. Four-credit courses that meet for 150 An introductory course that focuses on the four skills: speaking, reading, minutes per week require three additional hours of class preparation per writing and listening providing students with a basic knowledge of week on the part of the student in lieu of an additional hour of formal Italian linguistic structures, vocabulary and culture, which studied instruction. interdependently, comprise the Italian Language. Attributes: ALC, IPE. Mutually Exclusive: ITAL 1002. ITAL 2561. Reading Culture Through Literature. (4 Credits) ITAL 1002. Introduction to Italian II. (3 Credits) This course is designed to introduce students to different aspects of This course will enhance the reading, writing, speaking and listening skills Italian cultural tradition and history by closely reading representative acquired by students in Introduction to Italian I or from prior study. It will literary texts from the early and modern periods, in a variety of genres further promote a deeper understanding of Italian and its literary and including poetry, narrative, and drama. Students will acquire a technical cultural traditions. vocabulary and practice different interpretive strategies to speak to Prerequisite: ITAL 1001. continue the study of Italian literature and culture at the advanced level. Mutually Exclusive: ITAL 1001. The course¿s thematic focus, and the primary texts and secondary ITAL 1501. -

Sono Disponibili Gli Atti Della Seconda Edizione Di

Atti di Ciclo di incontri su e con scrittori del Novecento e contemporanei Siena, ottobre - novembre 2011 a cura del Comitato redazionale di INCONTROTESTO Progetto a cura di Giulia Romanin Jacur, Elena Stefanelli, Martina Tarasco. Comitato redazionale: Irene Baldoni, Giuditta Ciani, Sara Di Lorenzi, Annarita Ferranti, Caterina Fontanella, Milena Giuffrida, Maddalena Graziano, Susanna Grazzini, Chiara Licata, Elisa Olivo, Simona Palomba, Giulia Romanin Jacur, Claudia Russo, Elena Stefanelli, Martina Tarasco, Maria Rita Traina. Organizzazione degli incontri a cura di Livio Gambino, Antonino Garufo, Simona Palomba, Giulia Romanin Jacur, Martina Tarasco (su Andrea Zanzotto); Dania Dibitonto, Maddalena Graziano, Elisa Olivo, Francesco Vito- bello (intervista a Antonella Anedda e Franco Buffoni); Chiara Licata, Maria Livia Rennenkampff, Raffaello Rossi, Elena Stefanelli, Martina Tarasco, Irene Tinacci (intervista a Nanni Balestrini); Valeria Cavalloro, Giuditta Ciani, Milena Giuffrida, Susanna Grazzini, Simona Palomba, Claudia Russo, Martina Tarasco (su Primo Levi); Valeria Cavalloro, Francesca Lorenzoni, Elena Stefanelli, Francesco Vitobello (su Giovanni Giudici); Silvia Datteroni, Annarita Ferranti, Chiara Licata, Simona Palomba, Giulia Romanin Jacur, Elisa Russian, Francesco Vitobello (in- tervista a Walter Siti); Elisa Olivo, Giulia Romanin, Claudia Russo, Maria Rita Traina (su Edoardo Sanguineti); Sara Buti, Simone Calonaci, Giuditta Ciani, Caterina Fontanella, Elisa Russian, Elena Stefanelli (su Elsa Morante). Collaboratori riprese video e letture: Antonino Garufo, Margherita Gravagna. Progetto realizzato con il contributo dell’Azienda Regionale per il Diritto allo Studio, della Provincia di Siena; con il patrocinio della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia di Siena, Dipartimento di Filologia e Critica della letteratura; in compartecipazione con Pacini Editore. Grafica a cura diValeria Cavalloro, Giulio Deboni. Progetto grafico a cura diValeria Cavalloro, Francesco Tommasi. -

Qt8k730054 Nosplash Ca5ac71

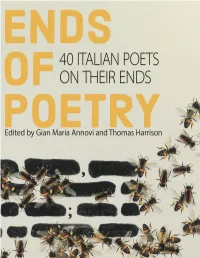

ENDS OF POETRY FORTY ITALIAN POETS ON THEIR ENDS EDITED BY Gian Maria Annovi and Thomas Harrison California Italian Studies eScholarship Publishing University of California Introduction copyright © 2019 by Gian Maria Annovi Poems and critical notes copyright © 2019 by the authors First Edition 2019 Cover image: Emilio Isgrò, Credo e non credo, 2010 acrylic on canvas on panel, in 27.55 x 39.37 (Tornabuoni Art). Detail. CONTENTS AN ENDLESS END 1 Antonella Anedda 12 Nanni Balestrini 17 Elisa Biagini 21 Carlo Bordini 26 Alessandro Broggi 31 Franco Buffoni 34 Nanni Cagnone 40 Maria Grazia Calandrone 45 Alessandra Carnaroli 51 Maurizio Cucchi 56 Stefano Dal Bianco 61 Milo De Angelis 66 Eugenio De Signoribus 71 Tommaso Di Dio 76 Fabrizio Falconi 81 Umberto Fiori 86 Biancamaria Frabotta 91 Gabriele Frasca 96 Giovanna Frene 101 Marco Giovenale 106 Massimo Gezzi 111 Mariangela Gualtieri 116 Mariangela Guàtteri 121 Andrea Inglese 126 Vivian Lamarque 131 Rosaria Lo Russo 136 Valerio Magrelli 141 Franca Mancinelli 146 Guido Mazzoni 151 Renata Morresi 156 Vincenzo Ostuni 161 Elio Pecora 166 Laura Pugno 171 Fabio Pusterla 176 Luigi Socci 181 Enrico Testa 186 Italo Testa 191 Fabio Teti 196 Gian Mario Villalta 201 Lello Voce 206 An Endless End Gian Maria Annovi Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? Those people were a kind of solution. K. P. Cavafy, “Waiting for the Barbarians” The end of poetry seems to be always on its way. More have announced it in the past than evoke it today. And yet, the end of poetry never comes. One could argue that this endless end functions conceptually like waiting for the arrival of the barbarians in one of K. -

Thursday (Mar 21) | Track 1 : 12:00 PM- 2:00 PM

Thursday (Mar 21) | Track 1 : 12:00 PM- 2:00 PM 1.29 Teaching the Humanities Online (Workshop) Chair: Susan Ko, Lehman College-CUNY Chair: Richard Schumaker, City University of New York Location: Eastern Shore 1 Pedagogy & Professional 1.31 Lessons from Practice: Creating and Implementing a Successful Learning Community (Workshop) Chair: Terry Novak, Johnson and Wales University Location: Eastern Shore 3 Pedagogy & Professional 1.34 Undergraduate Research Forum and Workshop (Part 1) (Poster Presentations) Chair: Jennifer Mdurvwa, SUNY University at Buffalo Chair: Claire Sommers, Graduate Center, CUNY Location: Bella Vista A (Media Equipped) Pedagogy & Professional "The Role of the Sapphic Gaze in Post-Franco Spanish Lesbian Literature" Leah Headley, Hendrix College "Social Acceptance and Heroism in the Táin " Mikaela Schulz, SUNY University at Buffalo "Né maschile né femminile: come la lingua di genere neutro si accorda con la lingua italiana" Deion Dresser, Georgetown University "Woolf, Joyce, and Desire: Queering the Sexual Epiphany" Kayla Marasia, Washington and Jefferson College "Echoes and Poetry, Mosques and Modernity: A Passage to a Muslim-Indian Consciousness" Suna Cha, Georgetown University "Nick Joaquin’s Tropical Gothic and Why We Need Philippine English Literature" Megan Conley, University of Maryland College Park "Crossing the Linguistic Borderline: A Literary Translation of Shu Ting’s “The Last Elegy”" Yuxin Wen, University of Pennsylvania "World Languages at Rutgers: A Web Multimedia Project" Han Yan, Rutgers University "Interactions Between the Chinese and the Jewish Refugees in Shanghai During World War II" Qingyang Zhou, University of Pennsylvania "“A Vast Sum of Conditions”: Sexual Plot and Erotic Description in George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss" Derek Willie, University of Pennsylvania "Decoding Cultural Representations and Relations in Virtual Reality " Brenna Zanghi, University at Buffalo "D.H. -

ITALIAN CONTEMPORARY POETS an Anthology

ITALIAN CONTEMPORARY POETS An Anthology Edited by Franco Buffoni Contents Preface Antonella Anedda gian Maria Annovi Nanni Balestrini Elisa Biagini Silvia Bre Franco Buffoni Maria grazia Calandrone giuseppe Conte Maurizio Cucchi Claudio damiani Milo de Angelis Roberto deidier Eugenio de Signoribus gianni d’Elia Paolo Febbraro Umberto Fiori Alessandro Fo Biancamaria Frabotta COPYRIghT @ 2016 FUIS gabriele Frasca FEdERAzIONE UNITARIA ITALIANA SCRITTORI Bruno galluccio By courtesy of Aragno edizioni, Arc, Bloodaxe Books, Crocetti, donzelli, Massimo gezzi Einaudi, Farrar Straus and giroux, Fazi, garzanti, Interlinea, Italic-Pequod, John Cabot U.P., Le Lettere, Marcos y Marcos, Mondadori, Nottetempo, Sossella. Andrea Inglese 3 Vivian Lamarque PrefaCe Valerio Magrelli This is the first anthology of contemporary Italian Francesca Matteoni poetry conceived and created in Italy entirely for a guido Mazzoni readership whose mother tongue or second language Aldo Nove is English. It is intended for international circulation Elio Pecora as a convenient instrument for the spread of Italian po - Laura Pugno etic thought. hence the lack of a parallel text and the restriction of selected authors to forty. Forty living Fabio Pusterla poets who have been fully active on the Italian literary Andrea Raos scene over recent years. Antonio Riccardi As the editor I much regret, due to limited space, Mario Santagostini that I could not include in this initiative all those poets who would have well deserved it. On the other hand, a Luigi Socci critical assessment of the situation in Italian poetry to - Luigia Sorrentino day is far more complex and varied than that of twenty Patrizia Valduga or thirty years ago. -

L I•) NOIDONNE I

Ti'?PtJl()ICIIIIIIIIIIII NOIOONNE WEEK RETE NEWS FOTO&VIDEO ASSOCIAZIONI SOSTIENICI noidonnt ...."'.. ., Toccare quello che resta SOGGETTO DOi\'NA:SCRITTURA E ALTREARTT Poesla/Barbara Carte· Essenzlallta di forme come accenslone e lncandescenza Sl I\IU:O IWI 5£S>llm •: \ IOU:N/-\ 01 CENDI.E• OMOm Ill\ llico1111'\wainiw,eh1bolR.Yi6•n11- tu11�••·111t111m.:011 •ri-er•ltlll Benassi Luca Lunedi, 03/10/2011 • Articolo pubblic.atonel 19 APRILE 2018 - Casa Circondariale di Teramo mensile NoiDonne di Settembre 2011 Ore 12:30 - locon1ro coo la sezfone remminile Non ce· ingcgncre svizzero che potrebbe migliorare la l'rV!+CUIUll!n:'dtf Jitn,111..1 ,......."11 INllI ddli, il.'lc9*t dcl cal.:Cle-umo� lt..,w,t,.11 i - perlez one primordiale di una cioiola o di un bicchiere, la TbiHa B1111ol.ini.P•ol11 Or1l-'flli.Asr;IMH M.!.a1Ctr,U i co mpiutezza d una forchena, l'essenzialc praticit.J di un peuinc. Vi sono formc apparentemcnce connaturate l', �� all'esscre umano, in grado di travalicare millenni c civilt.3, penctrando nel contcmporaneo tecnologico con iorza c funzionalit.J immutate. Sembra questo ii nocciolo di "Tangible Remains. Toccare quello che resta", l'ultimo libro della poctessa americana Barbara Carle, net quale una realta --Cm:nd.lin• DiS.btrcino nr.���I irancumata come da un gigantesco blackout lasda le cracce di ,...L11tia.o........ O'A•ito forme, sapori odori a essa leg ati. Cinquanta poesie, ognuna ....,.....,,,.... ,._. ,v,...,.. e �lnl'l• Crist.in.a. GWu1l11i'""*�"' ispirata a uno o piU oggen� cinquanta tasselli, reliquie che ,,._.,."_..,,,,....11 _ .... r. -

1 California State University Sacramento ITALIAN 111

California State University Sacramento ITALIAN 111 Introduction to Italian Literature II Fall 2015 Professoressa Barbara Carle Section 1 TR 3-4:15, Mariposa Hall 1002 office hours: W 2:30 – 5:30 Mariposa 2057 and by appointment tel: 278 6509 e-mail: [email protected] Catalog Description: ITAL 111 Introduction to Italian Literature II. Major developments in the literature of Italy from the Enlightenment movement of the 18th Century through the Twentieth Century. Analysis of the literary movements with emphasis on their leading figures, discussion of literary subjects, instruction in the preparation of reports on literary, biographical, and cultural topics. Taught in Italian. Prerequisite: Upper division standing and instructor permission. 3 units. Texts and Materials: All of the readings will be made available in PDF format from my web page. You will be required to go to the library and check out works by at least (3) of the poets on the reading list or the “Altri consigliati” or the list of anthologies in the Library. One of the requirements of the course will be to check out books from the library, and select a poem to present to the class. You will be asked to explain the poem, read it, and comment it. You should be able to achieve at least three of the main objectives below while presenting the texts. Twice during the semester you will write an explanation of a chosen poetic text after presenting it to the class. The written explanation should be between 3-6 typewritten pages, double-spaced, 12p font. Expect at least two quizzes on the vocabulary of the poems we read. -

Pubblicazioni N.57

PUBBLICAZIONI 2017 Vengono segnalate, in ordine alfabetico per autore (o curatore o parola- chiave), quelle contenenti materiali conservati nell’AP della BCLu e strettamente collegate a Prezzolini, Flaiano, Ceronetti, Chiesa ecc. Le pubblicazioni seguite dalle sigle dei vari Fondi includono documenti presi dai Fondi stessi. [Avant-gardes ], “Passim”, Bollettino dell’Archivio svizzero di letteratu- ra, n. 18, 2017 [Editoriale ; CHRISTA BAUMBERGER , PETER ERISMANN , MAGNUS WIELAND , DADA Original ; FABIEN DUBOSSON , VINCENT YERSIN , Cendrars, avant-gardiste à distance ; RUDOLF PROBST , Meret Oppenheim. Literatur und bildende Kunst ; FABIEN DUBOSSON , DENIS BUSSARD , Une avant-garde d’arrière-garde: La Voile latine (1904- 1911) ; CORINNA JÄGER -TREES , MARGIT GIGERL , Neue Litertur und Öffentlichkeit ; ULRICH WEBER , Graz sei Dank! Schweizerische- österreichische Querbezüge ; MAGNUS WIELAND , Avantgarden im Verlag: Arche - Walter Drucke - Urs Engeler Editor ; CHRISTA BAUMBERGER , ANNETTA GANZONI , DANIELE CUFFARO , Sprachsprünge. Sigls da lingua. Salti di lingua ; IRMGARD WIRZ , Avantgarde weiblich [Erica Pedretti, Hanna Johansen, Eleonore Frey, Birgit Kempker]; STÉPHANIE CUDRÉ -MAUROUX , FABIEN DUBOSSON , Érotisme et modernité littéraire (de 1945 à aujourd’hui) ; IRMGARD WIRZ , Avantgarden im Archiv. Rückblick auf die Ringvorlesung ; ANDREAS MAUZ , Avantgarden und Avantgardismus. Die SLA-Sommerakademie 2016 im Rückblick ; CLAUDIA CATHOMAS , Höhepunkte literarischer Mehrsprachigkeit im Engadiner Hochtal: Sprachsprünge in Sils vom 1. bis 3. September 2016 ; ASELLE PERSOZ , Du Maître-saucier à Un poisson hors de l’eau : quelques aspects de la genèse d’un roman ; YVONNE SIMMEN , CLAUDIA CATHOMAS , «Scriver per viver – viver per scriver»: Theo Candinas und sein Archiv .] LUCIANO LUISI, Su Luigi Bartolini , “l’immaginazione”, San Cesario di Lecce, n. 297, gennaio-febbraio 2017, pp. 18-19 78 LUCA SUCCHIARELLI, Luigi Bartolini e il Cantone Ticino , “Il Cantonetto”, rassegna letteraria bimestrale, Lugano, a. -

1 Assistant Professor of Modern Italian Literature Department of Romance

MARIA ANNA MARIANI Assistant Professor of Modern Italian Literature Department of Romance Languages and Literatures Center for Jewish Studies University of Chicago 1115 E. 58th Street, Chicago IL 60637 [email protected] FACULTY APPOINTMENTS ▪ 1st July 2015: Assistant Professor of Modern Italian Literature at the University of Chicago. ▪ 1st March 2013-30th June 2015: Assistant Professor of Italian at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea. ▪ 1st March 2011-28th February 2013: Full-Time Lecturer in Italian at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea. EDUCATION ▪ 1st September 2007-4th November 2010: Ph. D. in Italian Literature, Comparative Literature and Literary Theory at Università degli studi di Siena. Dissertation title: Memoria-racconto. Per una teoria dell’autobiografia contemporanea (Memory-Telling. For a Theory of Contemporary Autobiography). Supervisor: Prof. Guido Mazzoni). ▪ 1st September 2005-3rd April 2007: MA in Book Industry and Multimedia Publishing at Università per Stranieri di Siena. Dissertation title: Simulacri di Aron Hector Schmitz. Svevo e l’autobiografia come impostura (Aron Hector Schmitz’s Simulacra. Svevo and the Autobiography as Deception). Supervisors: Prof. Pietro Cataldi and Prof. Gabriele Frasca. Final Grade: 110/110 with merit. ▪ 1st September 2001-16th February 2005: BA in Literature and Philosophy at Università degli Studi di Siena. Dissertation title: «Petrolio» come riscrittura (Pasolini’s Petrolio as a rewriting process). Supervisor: Prof. Romano Luperini. Final Grade: 110/110 with merit. 1 PUBLICATIONS Books ▪ Primo Levi e Anna Frank. Tra testimonianza e letteratura (Primo Levi and Anne Frank. Between Testimony and Literature), Carocci, June 2018. Reviews. Print: Il Sole 24 Ore (07/08/2018), Avvenire (09/04/18), Italian Culture (05/19), Quaderni d’Italianistica (07/11/2019), Annali d’Italianistica (11/2019), Esperienze letterarie (04/2020), Italica (Fall 2019); Web: Librobreve (07/15/2018), Le parole e le cose (09/04/18), Minerva Web, official journal of the Senate (n.