The Road to Success IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition and Mortality Survey

NUTRITION AND MORTALITY SURVEY Tharparkar, Sanghar and Kamber Shahdadkhot districts of Sindh Province, Pakistan 18-25 March, 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ................................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2. Objective of the Study ............................................................................................................................... 6 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................................. 7 3.1 Study area ......................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Study population .............................................................................................................................. 7 3.3 Study design ...................................................................................................................................... 8 3.3.1 Sample size -

A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Rainfall and Drought Monitoring in the Tharparkar Region of Pakistan

remote sensing Article A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Rainfall and Drought Monitoring in the Tharparkar Region of Pakistan Muhammad Usman 1 and Janet E. Nichol 2,* 1 Centre for Geographical Information System, University of the Punjab, Lahore 54590, Pakistan; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton BN19RH, UK * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-9363-8044 Received: 6 January 2020; Accepted: 5 February 2020; Published: 10 February 2020 Abstract: The Tharpakar desert region of Pakistan supports a population approaching two million, dependent on rain-fed agriculture as the main livelihood. The almost doubling of population in the last two decades, coupled with low and variable rainfall, makes this one of the world’s most food-insecure regions. This paper examines satellite-based rainfall estimates and biomass data as a means to supplement sparsely distributed rainfall stations and to provide timely estimates of seasonal growth indicators in farmlands. Satellite dekadal and monthly rainfall estimates gave good correlations with ground station data, ranging from R = 0.75 to R = 0.97 over a 19-year period, with tendency for overestimation from the Tropical Rainfall Monitoring Mission (TRMM) and underestimation from Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS) datasets. CHIRPS was selected for further modeling, as overestimation from TRMM implies the risk of under-predicting drought. The use of satellite rainfall products from CHIRPS was also essential for derivation of spatial estimates of phenological variables and rainfall criteria for comparison with normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)-based biomass productivity. This is because, in this arid region where drought is common and rainfall unpredictable, determination of phenological thresholds based on vegetation indices proved unreliable. -

A Case Study of Mahsud Tribe in South Waziristan Agency

RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY By MUHAMMAD IRFAN MAHSUD Ph.D. Scholar DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (SESSION 2011 – 2012) RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY Thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Award of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE (December, 2018) DDeeddiiccaattiioonn I Dedicated this humble effort to my loving and the most caring Mother ABSTRACT The beginning of the 21st Century witnessed the rise of religious militancy in a more severe form exemplified by the traumatic incident of 9/11. While the phenomenon has troubled a significant part of the world, Pakistan is no exception in this regard. This research explores the role of the Mahsud tribe in the rise of the religious militancy in South Waziristan Agency (SWA). It further investigates the impact of militancy on the socio-cultural and political transformation of the Mahsuds. The study undertakes this research based on theories of religious militancy, borderland dynamics, ungoverned spaces and transformation. The findings suggest that the rise of religious militancy in SWA among the Mahsud tribes can be viewed as transformation of tribal revenge into an ideological conflict, triggered by flawed state policies. These policies included, disregard of local culture and traditions in perpetrating military intervention, banning of different militant groups from SWA and FATA simultaneously, which gave them the raison d‘etre to unite against the state and intensify violence and the issues resulting from poor state governance and control. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES

Heritage Foundation’s DRR-COMPLIANT SUSTAINABLE CONSTRUCTION BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES DRR-DRIVEN POST-FLOOD REHABILITATION IN SINDH Introduction to Heritage Foundation eritage Foundation established in 1980 is a Pakistan- based, not-for-profit, social and cultural entrepreneur organization engaged in research, publication and Hconservation of Pakistan’s cultural heritage. The Foundation has been instrumental in saving a large num- ber of heritage treasures and, as UNESCO team leader 2003- 2005, undertook the stabilization of the endangered Shish Ma- hal ceiling of the 16th c. Lahore Fort World Heritage Site. The Foundation publishes monographs and documents relat- ing to heritage and history of Pakistan as well as guides for her- itage safeguarding aspects. It has published a series of invento- ries of historic assets as National Register of Historic Places of Pakistan. In the National Register series, in addition to several Karachi documents listing over 600 historic buildings, docu- ments covering parts of Peshawar, the Siran Valley, Hazara District and Azad Kashmir have been published. Since 2000, its outreach arm KaravanPakistan has involved communities and youth in heritage safeguarding activities. Since 2005, as part of Heritage for Rehabilitation and Devel- opment Program, in partnership with Nokia and Nokia Sie- mens Network, Heritage Foundation has carried out work of rehabilitation of communities, particularly women, affected by the Earthquake 2005 in Northern Pakistan. A 3-year pro- gram, suppported by Scottish Government Fund, Glasgow University and Scottish Pakistan Association on disaster risk resistance (DRR) focusing on women is currently being car- ried out in the Siran Valley. The establishment of KIRAT, Kar- avanPakistan Institute for Research and Training in 2008 has helped in carrying out research and training on varied aspect of sustainable construction techniques drawn from traditional materials and vernacular methods. -

Building Back Stronger

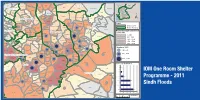

IOM One Room Shelters - 2011 Sindh Floods Response uc, manjhand odero lal village kamil hingoro jhando mari Punjab sekhat khirah Balochistan dasori San gha r ismail jo goth odero lal station khan khahi bilawal hingorjo Matiari roonjho khokhrapar matiari mirabad balouchabad tando soomro chhore bau khan pathan piyaro lund turk ali mari mirpurkhas-05 Sindh shaikh moosa daulatpur shadi pali tajpur pithoro shah mardan shah dhoro naro i m a khan samoon sabho kaplore jheluri Tando Allahpak singhar Yar mosu khatian ii iii iv missan tandojam dhingano bozdar hingorno khararo syed umerkot mirpur old haji sawan khan satriyoon Legend atta muhammad palli tando qaiser araro bhurgari began jarwar mir ghulam hussain Union Council bukera sharif tando hyder dengan sanjar chang mirwah Ume rkot District Boundary hoosri gharibabad samaro road dad khan jarwar girhore sharif seriHyd erabmoolan ad Houses Damaged & Destroyed tando fazal chambar-1 chambar-2 Mirpur Khas samaro kangoro khejrari - Flood 2011 mir imam bux talpur latifabad-20 haji hadi bux 1 - 500 kot ghulam muhammad bhurgari mir wali muhammad latifabad-22 shaikh bhirkio halepota faqir abdullah seri 501 - 1500 ghulam shah laghari padhrio unknown9 bustan manik laghari digri 1501 - 2500 khuda dad kunri 2501 - 3500 uc-iii town t.m. khan pabban tando saindad jawariasor saeedpur uc-i town t.m. khan malhan 3501 - 5000 tando ghulam alidumbalo shajro kantio uc-ii town t.m. khan phalkara kunri memon Number of ORS dilawar hussain mir khuda bux aahori sher khan chandio matli-1 thari soofan shah nabisar road saeed -

Bani of Bhagats-Part II.Pmd

BANI OF BHAGATS Complete Bani of Bhagats as enshrined in Shri Guru Granth Sahib Part II All Saints Except Swami Rama Nand And Saint Kabir Ji Dr. G.S. Chauhan Publisher : Dr. Inderjit Kaur President All India Pingalwara Charitable Society (Regd.) Amritsar-143001 Website:www.pingalwara.co; E-mail:[email protected] BANI OF BHAGATS PART : II Author : G.S. Chauhan B-202, Shri Ganesh Apptts., Plot No. 12-B, Sector : 7, Dwarka, New Delhi - 110075 First Edition : May 2014, 2000 Copies Publisher : Dr. Inderjit Kaur President All India Pingalwara Charitable Society (Regd.) Amritsar-143001 Ph : 0183-2584586, 2584713 Website:www.pingalwara.co E-mail:[email protected] (Link to download this book from internet is: pingalwara.co/awareness/publications-events/downloads/) (Free of Cost) Printer : Printwell 146, Industrial Focal Point, Amritsar Dedicated to the sacred memory of Sri Guru Arjan Dev Ji Who, while compiling bani of the Sikh Gurus, included bani of 15 saints also, belonging to different religions, castes, parts and regions of India. This has transformed Sri Guru Granth Sahib from being the holy scripture of the Sikhs only to A Unique Universal Teacher iii Contentsss • Ch. 1: Saint Ravidas Ji .......................................... 1 • Ch. 2: Sheikh Farid Ji .......................................... 63 • Ch. 3: Saint Namdev Ji ...................................... 113 • Ch. 4: Saint Jaidev Ji......................................... 208 • Ch. 5: Saint Trilochan Ji .................................... 215 • Ch. 6: Saint Sadhna Ji ....................................... 223 • Ch. 7: Saint Sain Ji ............................................ 227 • Ch. 8: Saint Peepa Ji.......................................... 230 • Ch. 9: Saint Dhanna Ji ...................................... 233 • Ch. 10: Saint Surdas Ji ...................................... 240 • Ch. 11: Saint Parmanand Ji .............................. 244 • Ch. 12: Saint Bheekhan Ji................................ -

Drought Assessment Report Districts Tharparkar and Umerkot

Rapid Assessment Report Draft (19th November 2014) Drought Assessment Report Districts Tharparkar and Umerkot 26th October -- 1st November 2014 Consortium Management Unit PEFSA V Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... 4 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Background ............................................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 6 2.2.1 Objective ....................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2.2 Approach to Assessment .............................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Demographics ......................................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Taluka wise Affected Union Councils of District Tharparkar .................................................. 9 3 MAIN FINDINGS ........................................................................................................... 11 3.1 Affected population and Migration ...................................................................................... 11 3.2 Drought Intensity -

Crisis Response Bulletin Page 1-16

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN January 20, 2015 - Volume: 1, Issue: 1 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 2-25 Gambling On The Monsoon: ‘Thar Has The Potential of Being a Self-Sustaining Oasis' 02 Pakistan Red Cresecent Society (PRCS) Response to Monsoon 2014 03 Natural Calamities Section 2-8 192 militancy cases against banned outfits to be heard on priority 09 Safety and Security Section 9-16 60 scanned counterfeit passports, army, police cards seized 10 Public Services Section 17-25 Nisar orders communication, financial blockade of terrorists 11 Pakistan, Japan to increase cooperation in economy, security 12 Pakistan, Saudi Arabia mull steps to choke terror funding 13 Maps 26-35 Karachi airport attack case: ATC issues arrest warrants for TTP chief, 7 others 14 Country’s first high-security prison ‘ready for opening’ 15 Urdu News 55-36 Petrol crisis strikes alarming levels in Punjab on sixth day 17 Incongruity: Power plants stay closed despite cheaper oil 18 Natural Calamities Section 55 City CNG outlets open for two days in Lahore 19 Safety and Security section 54-47 CNG sale should be allowed until petrol supply is restored 20 Public Service Section 46-36 Power crisis: FPCCI chief urges government to purchase power from idle RFO plants 21 WEATHER SITUATION MAP OF PAKISTAN CNG STATION LOAD MANAGEMENT IN PUNJAB DISTRICT RAWALPINDI & ISLAMABAD ELECTRICITY FUEL CRISIS MAP OF DISTRICT ISLAMABAD & MAPS LOAD MANAGEMENT MAP PUNJAB PROVINCE FUEL CRISIS MAP OF LAHORE THARPARKAR - DROUGHT SITUATION MAP FATA AND KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA -

Paper Template

International Journal of Arts, Culture, Design & Language Kambohwell Publishers Enterprise Vol. 6, Issue 06, PP. 17-23, June 2019 wwww.kwpublisher.com Evolution of Mirror Embroidery in Two Villages of Sanghar Sindh Saba Qayoom Leghari, Bhai Khan Shar Centre of Excellence in Arts & Design, MUET Jamshoro. Abstract— The tradition of mirror embroidery is one of the evolved through modifications and enhancements from time to major features of regional embroideries of Sindh. Several time. Foreign invasions and migrations of people from other studies on embroideries of Sindh have been conducted but regions have further enriched the work by intermixing of seldom research work has been done, particularly on mirror different cultures in this region [4]. embroidery. It is in the backdrop of this and owing to the Researchers from different parts of the world have worked immense richness of embroidery of Sindh this study has been on the indigenous embroideries of Sindh. Several authors [4] conducted. This study focuses on identifying the lost [5] described the mirror embroideries of different regions of characters and changes within mirror embroidery, since the Sindh, which includes: Ghotki, Shikarpur, Jacobabad, past three decades. Having rich traditions in embroidery in Khairpur, Sukkur, Mirpur Mathelo, Thano Bula Khan, Thatta, lower Sindh, Sanghar District has been chosen as an area of Badin, Hyderabad, Hala, Nawabshah, Mirpurkhas, Sanghar, study for this paper. In order to have a closer qualitative study, Kashmore and multiple regions of Thaparkar particularly two villages; Moulvi Khair Muhammad (Bakhoro) and Haji Umarkot, Chachro, , Diplo, Nagarparkar and Mithi. Much of Abdul Karim Laghari (Patti), were mainly surveyed along this literature provides sufficient detail about different with some other areas. -

Spatio-Temporal Changes in Economic Development: a Case Study of Sindh Province

Karachi University Journal of Science, 2012, 40, 25-30 25 Spatio-temporal Changes in Economic Development: A case study of Sindh Province Razzaq Ahmed1 and Khalida Mahmood2,* 1Department of Geography, Federal Urdu University of Arts Sciences and Technology, Karachi and 2Department of Geography, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan Abstract: This study has been conducted at a time when Pakistan is passing through an important phase of economic development and reconstruction. Devolution has become an important aspect of the planning and decision making process. Decentralization is being emphasized by both public and private sectors of development. In such a situation, present study focuses on the evaluation of the past and present patterns of the levels of development in various districts of the province of Sindh. This research will certainly contribute to an understanding of the development patterns in the province. Key Words: composite index, level of development, ranking, socio-economic inequality, Z-score. INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK Sindh has experienced considerable urbanization since To measure the level of development of the districts of independence in 1947, which has resulted in the explosive Sindh, twelve variables have been employed on thirteen 1 growth of urban centers like Karachi, Hyderabad and districts of 1981 and sixteen districts of 1998 . These Sukkur. The growth of Karachi in particular has been variables are non-agricultural labor force, employment in phenomenal. Its exceptional growth as compared to the rest manufacturing, immigration, own farm, cultivated area, of Sindh, which is basically rural in nature, brings out unique population potential, manufacturing value added (rupees per patterns of socio-economic inequality. -

PAKISTAN – SINDH May – December 2019 Issued in November 2019

IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS PAKISTAN – SINDH May – December 2019 Issued in November 2019 Key Figures May – August 2019 SAM (Severe Acute 365,209 Malnutrition) Number of cases 1,000,458 MAM (Moderate Acute Number of 6-59 months children acutely 635,249 Malnutrition) Number of cases malnourished IN NEED OF TREATMENT GAM (Global Acute 1,000,458 Malnutrition) Number of cases How Severe, How Many and When – Acute malnutrition is a major public health problem in all the 8 drought affected districts in the Sindh province. Two districts in the province have Extremely Critical levels (IPC AMN Phase 5) of acute malnutrition – i.e. about every third child in these districts is suffering from acute malnutrition. Six other districts have Critical levels (IPC AMN Phase 4) of acute malnutrition. Although the 6 districts are classified in IPC AMN Phase 4, 2 of them have acute malnutrition levels very close to IPC AMN Phase 5. Where – Among the 8 drought affected districts notified by the Government of Sindh in 2018, the districts with Extremely Critical levels (IPC AMN Phase 5) of acute malnutrition are namely Tharparkar and Umerkot. The other 6 districts – Jamshoro, Kambar Shahdadkot, Badin, Dadu, Sanghar, and Thatta – are classified as being in IPC AMN Phase 4. Of these 6 districts, 2 of them, i.e. Kambar Shahdadkot and Badin, have acute malnutrition levels very close to IPC AMN Phase 5. Why – The major factors contributing to acute malnutrition include very poor quality and quantity of food, high food insecurity, poor sanitation coverage, and high incidence of low birthweight.