Nara Desert, Pakistan Part I: Soils, Climate, and Vegetation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Article Biological Method in Stabilization of Sand Dunes Using the Ornamental Plants and Woody Trees: Review Article

Journal of Innovations in Pharmaceuticals and Biological Sciences JIPBS www.jipbs.com ISSN: 2349-2759 Review article Biological method in stabilization of sand dunes using the ornamental plants and woody trees: Review article Metwally S.A.*1, Abouziena H.F.2, Bedour M.H. Abou- Leila3, M.M. Farahat1, E. El. Habba1 1Department of Ornamental Plants and Woody Trees, National Research Centre, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt, 12622. 2Department of Botany, National Research Centre, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt, 12622. 3 Department of Water Relation and Field irrigation, National Research Centre, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt, 12622. Abstract Sand dunes are considered one of the most obstacles that face the horizontal or vertical expansion of agriculture in the desert. Sand dunes are a collection of a loose grouping of sand on the land surface in the form of a pile with top. In the recent years, increasing attention has been taken to cultivate the timber trees and ornamental plants in a narrow range to combat the desertification, sand encroachment and sand dunes. The climate factors are characterized by high temperature, strong winds laden with sand and sandy dunes, lead to soil erosion and remove the fertility soil in the surface layer, and destroying cultivated lands. Therefore, it's important to planting windbreaks and stabilization sand dunes to reduce the damage and loss of all areas of development aspects. The methods used for combating the sand dunes can be classified into two types; biological methods or plant measure and the second are the mechanical methods or engineering measure. We will focus in this article on the biological methods where the trees, shrubs and grasses are planted. -

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity

Sand Dune Systems in Iran - Distribution and Activity. Wind Regimes, Spatial and Temporal Variations of the Aeolian Sediment Transport in Sistan Plain (East Iran) Dissertation Thesis Submitted for obtaining the degree of Doctor of Natural Science (Dr. rer. nat.) i to the Fachbereich Geographie Philipps-Universität Marburg by M.Sc. Hamidreza Abbasi Marburg, December 2019 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Christian Opp Physical Geography Faculty of Geography Phillipps-Universität Marburg ii To my wife and my son (Hamoun) iii A picture of the rock painting in the Golpayegan Mountains, my city in Isfahan province of Iran, it is written in the Sassanid Pahlavi line about 2000 years ago: “Preserve three things; water, fire, and soil” Translated by: Prof. Dr. Rasoul Bashash, Photo: Mohammad Naserifard, winter 2004. Declaration by the Author I declared that this thesis is composed of my original work, and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the text. I have clearly stated the contribution by others to jointly-authored works that I have included in my thesis. Hamidreza Abbasi iv List of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. General Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Introduction and justification ........................................................................................................ -

THE STORY OP LORETO By

J THE STORY OP LORETO / By ' The following story is written in the hope that the reader J·lill somehm share y gratitude to a small Asian village. There ' s a very strong reason for this need to say 11 thanJr you 11 • Few men can give themselves totally to a t ask and ,mllr mmy from the cene unscathed. Such ,ms t he comm itmen t of the .1 1 :ri ter to the village of Lo reto i n the deserts of 1\Test Pakistan o The story is therefore told with a deep reverence for a people I sincerely love. Prar God, it is told well o • • 11 Even if my tongue should cleave to the roof of m mouth , I will not forget theeo 11 •• ISAIAH ,, /. The Indus Ili ver, as it hurtles do,m from its feed bed in the ,. Himalay Mountains , continuously changes course on a two thousand' mile j ourney to the seao Over the centuries, this fanning movement across the plains has deposited one of the most fertile agricultural top soils i n the world,. The depth of t his alluvial oil is proxi mate to inexhaustible. I n this lies the wealth of West Padstan, and particularly of t he Punjab Province; Bo rdering the central stretches of the Indus River, on the east bank, i~ an area call ed the ThaJ Deserto Compared to the other arees of the Punj ab, it is a poor co1sin Extremes of torrid desert he~t a 1 iminutive deer (similar in size to the medieval nicorn ) we re its only distinguishing features until the year 19~7. -

Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District

PAKISTAN - Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District Union council ranking exercise, coordinated by UNOCHA and UNDP, is a joint effort of Government and humanitarian partners Community Restoration Food Education in the notified districts of 2011 floods in Sindh. Its purpose is to: Identify high priority union councils with outstanding needs. SHAHEED SHAHEED SHAHEED BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR Facilitate stackholders to plan/support interventions and divert Shah Shah Shah Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Gujri Gujri resources where they are most needed. Gul Gul Gujri Khadro Khadwari Khadro Khadwari Gul Khadro Khadwari Muhammad Muhammad Muhammad Laghari Laghari Laghari Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Provide common prioritization framework to clusters, agencies Shah Shah Serhari Chakar Kanhar Barhoon Barhoon Barhoon Shah Mardan Abad Mardan Abad Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mardan Abad Mian Chutiaryoon Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Khan Khan Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Khan Sanghar 1 and donors. Faqir HingoroLaghari Laghari Laghari Faqir Hingoro Faqir Hingoro Kurkali Kurkali Kurkali Jatia Jatia Jatia Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Manik Manik Manik Tahim Khipro Tahim Khipro First round of this exercise is completed from February - March Khori Khori Tahim Khipro Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Khori Pero Jan Nawaz DarhoonTando Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo Nauabad Nauabad Nauabad 2012. -

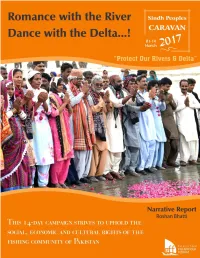

Caravan Report

1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Background: If there is ever to be a Third World War, many believe it will be fought over water, with South Asia serving as the flashpoint. The region houses a quarter of the world’s population and has less than 5 percent of the global annual renewable water resources. Low water availability per person and high frequency of extreme weather events, including severe droughts, further increase the vulnerability of the area. Any disturbance by the country upstream is likely to impact life downstream. Also, as heightened interests to tame and exploit a river through dams, canals and hydel projects suggest, this region will be a zone of constant confrontations in the future. The vision 2025 of Pakistan clearly indicates that the existing flow of water of rivers will be diverted through building various mega schemes for water conservation for energy and agricultural purposes. Such decisions and policies based on vested political interests will further aggravate the socio-economic conditions of deltaic communities of the Sindh. A large water share of the River Indus is utilized by Punjab Province. Resultantly, the lower end of the River Indus that used to be known as “Mighty River Indus” has been reduced to the level of canal shows only tiny inconsistent storage of water. Such a massive destruction of the River Indus has led to the death of livelihood of the deltaic people. The Pakistan government has been planning to build more dams on Indus River. The PFF believes that the indigenous people along with the other natural habitat have the basic right to use the land and water first. -

Slndh IRRIGATION & DRAINAGE AUTHORITY

38554 OSMANI & co (PVT ) LTD , &ALL~OSMANI - Consulting Eng~neers- Arch~tects Planners Engmeenng &chLec(ure.Ramm~ Mqpng. Tshology Public Disclosure Authorized SlNDH IRRIGATION & DRAINAGE AUTHORITY INTEGRATED SOCIAL & ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (ISEA) FOR WATER SECTOR IMPROVEMENT Phase-l PROJECT (WSIP-I) Public Disclosure Authorized November, 2006 Location of Sindh Province of Pakistan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SlNDH IRRIGATION & DRAINAGE AUTHORITY INTEGRATED SOCIAL & ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (ISEA) FOR WATER SECTOR IMPROVEMENT PHASE-I PROJECT (WSIP-I) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ..................... ......................................................................................................1 1.1 The Basic Issue........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Irrigation Sector Background ...............................................................................................................................1 1.3 Project Objectives............... .. ..............................................................................................................................2 1.4. Project Area .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Project Components ................................................................................................................................................3 -

A Mesolithic Site in the Thal Desert of Punjab (Pakistan)

Asian Archaeology https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-019-00024-z FIELD WORK REPORT Mahi Wala 1 (MW-1): a Mesolithic site in the Thal desert of Punjab (Pakistan) Paolo Biagi 1 & Elisabetta Starnini2 & Zubair Shafi Ghauri3 Received: 4 April 2019 /Accepted: 12 June 2019 # Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology (RCCFA), Jilin University and Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2019 1Preface considered by a few authors a transitional period that covers ca two thousand years between the end of the Upper The problem of the Early Holocene Mesolithic hunter-gatherers Palaeolithic and the beginning of the Neolithic food producing in the Indian Subcontinent is still a much debated topic in the economy (Misra 2002: 112). The reasons why our knowledge prehistory of south Asia (Lukacs et al. 1996; Sosnowska 2010). of the Mesolithic period in the Subcontinent in general is still Their presence often relies on knapped stone assemblages insufficiently known is due mainly to 1) the absence of a de- characterised by different types of geometric microlithic arma- tailed radiocarbon chronology to frame the Mesolithic com- tures1 (Kajiwara 2008: 209), namely lunates, triangles and tra- plexes into each of the three climatic periods that developed pezes, often obtained with the microburin technique (Tixier at the beginning of the Holocene and define a correct time-scale et al. 1980; Inizan et al. 1992; Nuzhniy 2000). These tools were for the development or sequence of the study period in the area first recorded from India already around the end of the (Misra 2013: 181–182), 2) the terminology employed to de- nineteenth century (Carleyle 1883; Black 1892; Smith scribe the Mesolithic artefacts that greatly varies author by au- 1906), and were generically attributed to the beginning thor (Jayaswal 2002), 3) the inhomogeneous criteria adopted of the Holocene some fifty years later (see f.i. -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Comparative Morphological and Biochemical Studies of Salvadora Species Found in Sindh, Pakistan

Pak. J. Bot., 42(3): 1451-1463, 2010. COMPARATIVE MORPHOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL STUDIES OF SALVADORA SPECIES FOUND IN SINDH, PAKISTAN FARZANA KOREJO1,2, SYED ABID ALI2,*, SYEDA SALEHA TAHIR1, MUHAMMAD TAHIR RAJPUT1 AND MUHAMMAD TUAHA AKHTER2 1Institute of Botany, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Sindh, Pakistan 2HEJ Research Institute of Chemistry, International Centre for Chemical and Biological Sciences (ICCBS), University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Salvadoraceae is a small family comprising of three genera viz., Azima, Dobera & Salvadora. Salvadora 10 species are distributed mainly in the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa and Asia. In Pakistan it is represented by a single genus Salvadora with so far, two morphologically distinct species i.e., S. persica L. and S. oleoides Decne. In the present investigation, a comparative and comprehensive leaf, branch, fruit, seed, and pollen grain macro and micro morphological characters have been analyzed and complemented with chemotaxonomy of the seed proteins as biochemical markers for identifications. As expected taxonomical characters within the Salvadora species revealed great vegetative morphological differences, especially plant length and width. Floral morphological characters appear to be more stable, except the fruit colours which are different. Furthermore, sizes and the anatomical characters of the leaf, branch, seed and pollen grain studied by scanning electron microscopy revealed that in contrast to S. oleoides Decne much intra-species variation exist in S. persica L. and at least two types and/or varieties are available in Sindh, Pakistan. Introduction The genus Salvadora belongs to the family Salvadoraceae, comprising of three genera (i.e. -

Conservation of Grassland Plant Genetic Resources Through People Participation

University of Kentucky UKnowledge International Grassland Congress Proceedings XXIII International Grassland Congress Conservation of Grassland Plant Genetic Resources through People Participation D. R. Malaviya Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute, India Ajoy K. Roy Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute, India P. Kaushal Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute, India Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc Part of the Plant Sciences Commons, and the Soil Science Commons This document is available at https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc/23/keynote/35 The XXIII International Grassland Congress (Sustainable use of Grassland Resources for Forage Production, Biodiversity and Environmental Protection) took place in New Delhi, India from November 20 through November 24, 2015. Proceedings Editors: M. M. Roy, D. R. Malaviya, V. K. Yadav, Tejveer Singh, R. P. Sah, D. Vijay, and A. Radhakrishna Published by Range Management Society of India This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant and Soil Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Grassland Congress Proceedings by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conservation of grassland plant genetic resources through people participation D. R. Malaviya, A. K. Roy and P. Kaushal ABSTRACT Agrobiodiversity provides the foundation of all food and feed production. Hence, need of the time is to collect, evaluate and utilize the biodiversity globally available. Indian sub-continent is one of the world’s mega centers of crop origins. India possesses 166 species of agri-horticultural crops and 324 species of wild relatives. -

World Bank Documents

The World Bank Report No: ISR10098 Implementation Status & Results Pakistan Sindh Water Sector Improvement Project Phase I (P084302) Operation Name: Sindh Water Sector Improvement Project Phase I (P084302) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 12 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 08-Jun-2013 Country: Pakistan Approval FY: 2008 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: SOUTH ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 18-Sep-2007 Original Closing Date 30-Apr-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 01-Jan-2013 Last Archived ISR Date 16-Oct-2012 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 26-Dec-2007 Revised Closing Date 28-Feb-2015 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The overarching project objective is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of irrigation water distribution in three AWBs (Ghotlu, Nara and Left Bank), particularly with respect to measures of reliability, equity and user satisfaction. This would be achieved by: (a) deepening and broadening the institutional reforms that are already underway in Sindh; (b) improving the irrigation system in a systematic way covering key hydraulic infrastructure, main and branch canals, and distributaries and minors; and (c) enhancing long-term sustainability o f irrigation system through participatory irrigation management and developing institutions for improving operation and maintenance of the system and cost recovery. The improved water management would lead to increased agricultural production, employment and incomes over some Public Disclosure Authorized about 1.8 million ha or more than 30 percent o f the irrigated area in Sindh, and one of the poorest regions o f the country. -

Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan

Socio#Hydrology of Channel Flows in Complex River Basins: Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Wescoat, James L., Jr. et al. "Socio-Hydrology of Channel Flows in Complex River Basins: Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan." Water Resources Research 54, 1 (January 2018): 464-479 © 2018 The Authors As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2017wr021486 Publisher American Geophysical Union (AGU) Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/122058 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ PUBLICATIONS Water Resources Research RESEARCH ARTICLE Socio-Hydrology of Channel Flows in Complex River Basins: 10.1002/2017WR021486 Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan Special Section: James L. Wescoat Jr.1 , Afreen Siddiqi2 , and Abubakr Muhammad3 Socio-hydrology: Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of 1School of Architecture and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2Institute of Data, Coupled Human-Water Systems, and Society, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 3Lahore University of Management Systems Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan Key Points: This paper presents a socio-hydrologic analysis of channel flows in Punjab province of the Coupling historical geographic and Abstract statistical analysis makes an Indus River basin in Pakistan. The Indus has undergone profound transformations, from large-scale canal irri- important contribution to the theory gation in the mid-nineteenth century to partition and development of the international river basin in the and methods of socio-hydrology mid-twentieth century, systems modeling in the late-twentieth century, and new technologies for discharge Comparing channel flow entitlements with deliveries sheds measurement and data analytics in the early twenty-first century.