River Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

Mineral Springs of Saratoga Springs and Ballston Spa Coloring Book

A Standards-Aligned Project & Puzzle Guide for Grades K-4 Mineral Springs of Saratoga Springs and Ballston Spa Coloring Book ISBN: 978-0-9965073-2-5 Written & Illustrated by Jacqueline S. Gutierrez Published by Sprouting Seed Press My hope is to raise awareness of the beauty and significance of these wonderful gifts of nature, to encourage maintenance and preservation of the existing springs, and hopefully to provide interest in the restoration of some previously decommissioned springs. The mineral springs of Saratoga Springs and Ballston Spa are a rare natural resource since there are few such places in the world where clean, drinkable mineral water springs are available. - Jacqueline S. Gutierrez Guide created by Debbie Gonzales, MFA 2 The puzzles and projects featured in this guide are intented to support the content presented in the Mineral Springs of Saratoga Springs and Ballston Spa Coloring Book. Students are encouraged to preuse the coloring book for the solutions to the puzzles presented in this guide. Students may work through the puzzles and projects in either an individual or collaborative manner. Table of Contents Historical Mix & Match Puzzle ..................................................................................................................3 Saratoga Springs Vertical Puzzle ...........................................................................................................4 The Minerals of Saratoga Mineral Springs ......................................................................................... -

Springs of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIBECTOB WATER- SUPPLY PAPER 338 SPRINGS OF CALIFORNIA BY GEKALD A. WARING WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 CONTENTS. Page. lntroduction by W. C. Mendenhall ... .. ................................... 5 Physical features of California ...... ....... .. .. ... .. ....... .............. 7 Natural divisions ................... ... .. ........................... 7 Coast Ranges ..................................... ....•.......... _._._ 7 11 ~~:~~::!:: :~~e:_-_-_·.-.·.·: ~::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::: ::: 12 Sierra Nevada .................... .................................... 12 Southeastern desert ......................... ............. .. ..... ... 13 Faults ..... ....... ... ................ ·.. : ..... ................ ..... 14 Natural waters ................................ _.......................... 15 Use of terms "mineral water" and ''pure water" ............... : .·...... 15 ,,uneral analysis of water ................................ .. ... ........ 15 Source and amount of substances in water ................. ............. 17 Degree of concentration of natural waters ........................ ..· .... 21 Properties of mineral waters . ................... ...... _. _.. .. _... _....• 22 Temperature of natural waters ... : ....................... _.. _..... .... : . 24 Classification of mineral waters ............ .......... .. .. _. .. _......... _ 25 Therapeutic value of waters .................................... ... ... 26 Analyses -

Kalamazoo River Assessment

ATUR F N AL O R T E N S E O U M R T C R E A S STATE OF MICHIGAN P E DNR D M ICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Number 35 September 2005 Kalamazoo River Assessment Jay K. Wesley www.michigan.gov/dnr/ FISHERIES DIVISION SPECIAL REPORT MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES FISHERIES DIVISION Special Report 35 September 2005 Kalamazoo River Assessment Jay K. Wesley MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES (DNR) MISSION STATEMENT “The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is committed to the conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the State’s natural resources for current and future generations.” NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION (NRC) STATEMENT The Natural Resources Commission, as the governing body for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, provides a strategic framework for the DNR to effectively manage your resources. The NRC holds monthly, public meetings throughout Michigan, working closely with its constituencies in establishing and improving natural resources management policy. MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES NON DISCRIMINATION STATEMENT The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) provides equal opportunities for employment and access to Michigan’s natural resources. Both State and Federal laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, disability, age, sex, height, weight or marital status under the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 as amended (MI PA 453 and MI PA 220, Title V of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 as amended, and the Americans with Disabilities Act). If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire additional information, please write: HUMAN RESOURCES Or MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL RIGHTS Or OFFICE FOR DIVERSITY AND CIVIL RIGHTS MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES CADILLAC PLACE US FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE PO BOX 30028 3054 W. -

Geothermal Hydrology of Valles Caldera and the Southwestern Jemez Mountains, New Mexico

GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO By Frank W. Trainer, Robert J. Rogers, and Michael L. Sorey U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER Albuquerque, New Mexico 2000 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Information Services Water Resources Division Box 25286 5338 Montgomery NE, Suite 400 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Albuquerque, NM 87109-1311 Information regarding research and data-collection programs of the U.S. Geological Survey is available on the Internet via the World Wide Web. You may connect to the Home Page for the New Mexico District Office using the URL: http://nm.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................ 2 Purpose and scope........................................................................................................................ -

An Investigation of the Interrelationships Among

AN INVESTIGATION OF THE INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG STREAMFLOW, LAKE LEVELS, CLIMATE AND LAND USE, WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE BATTLE RIVER BASIN, ALBERTA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Civil Engineering by Ross Herrington Saskatoon, Saskatchewan c 1980. R. Herrington ii The author has agreed that the Library, University of Ssskatchewan, may make this thesis freely available for inspection. Moreover, the author has agreed that permission be granted by the professor or professors who supervised the thesis work recorded herein or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which the thesis work was done. It is understood that due recognition will be given to the author of this thesis and to the University of Saskatchewan in any use of the material in this thesiso Copying or publication or any other use of the thesis for financial gain without approval by the University of Saskatchewan and the author's written permission is prohibited. Requests for permission to copy or to make any other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Civil Engineering Uni ve:rsi ty of Saskatchewan SASKATOON, Canada. iii ABSTRACT Streamflow records exist for the Battle River near Ponoka, Alberta from 1913 to 1931 and from 1966 to the present. Analysis of these two periods has indicated that streamflow in the month of April has remained constant while mean flows in the other months have significantly decreased in the more recent period. -

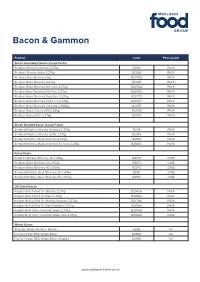

Bacon & Gammon

Bacon & Gammon Product Code Pricing Unit Sliced Unsmoked Bacon (Large Packs) Rindless Streaky Stirchley 2.27kg B203 PACK Rindless Streaky Selfar 2.27kg B203S PACK Rindless Back Stirchley 2kg B207D2 PACK Rindless Back Stirchley 2.27kg B207D PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Dry Cure 2.27kg B207DA PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Rib Free 2.27kg B207DR PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Supertrim 2.27kg B207ST PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Thick Cut 2.27kg B207DT PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Catering 2.268kg B207E PACK Rindless Back Classic (A11) 2.25kg B207M PACK Rindless Back Selfar 2.27kg B207S PACK Sliced Smoked Bacon (Large Packs) Smoked Rindless Streaky Stirchley 2.27kg B204 PACK Smoked Rindless Streaky Selfar 2.27kg B204S PACK Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 2.27kg B218D PACK Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley Dry Cure 2.27kg B218DC PACK Retail Packs Rindless Streaky Stirchley 20 x 454g B2031 CASE Rindless Back Stirchley 20 x 454g B2071 CASE Rindless Back Stirchley 40 x 200g B207C CASE Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 20 x 454g B2181 CASE Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 40 x 200g B218C CASE UK Sliced Bacon Knights British Rind On Streaky 2.27kg B206UK PACK Knights British Rind On Back 2.27kg B208UK PACK Knights British Rind On Streaky Smoked 2.27kg B217UK PACK Knights British Rind On Back Smoked 2.27kg B219UK PACK Knights British Dry Cured R/L Back 2.27kg B207UD PACK Knights British Dry Cured R/L Back Smk 2.27kg B218UD PACK Whole Bacon Stirchley Whole Rindless Streaks B258 KG Danish Crown BSD Whole Backs B255D KG Danish Crown BSD Whole Backs Smoked B259D -

Louise Simone Armshaw

1 ‘Do the duty that lies nearest to thee’: Elizabeth Gaskell, Philanthropy and Writing Louise Simone Armshaw Submitted by Louise Simone Armshaw to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Master of Philosophy in English September 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 2 3 Abstract This thesis examines the relationship between Gaskell’s philanthropy and her three social problem novels. Examining Gaskell in the context of Victorian philanthropy, I will argue that this is a relationship of far greater complexity than has previously been perceived. Gaskell’s Unitarian faith will be of particular relevance as different denominations often had unique approaches to philanthropy, and I will begin by examining Gaskell’s participation with philanthropy organised by her congregation, taking the charity bazaar as my example of this. Examining Gaskell’s three social problem novels in chronological order I will demonstrate that Gaskell rejects these forms of organised Victorian philanthropy, referred to as ‘associated philanthropy,’ in favour of developing her own vision of philanthropy in her novels. I will examine how Gaskell’s participation with ‘associated philanthropy,’ and the individual pursuit of her own philanthropic interests, shapes the development of her philanthropic vision in her fiction. -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

Ak2 : the Coming of Age of a New Auckland

AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE A NEW AUCKLAND PREVIOUSLY UNAVAILABLE PREVIOUSLY AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE OF A NEW AUCKLAND AK2: The Coming of Age of a New Auckland Published June 2014 by: Previously Unavailable www.previously.co [email protected] © 2014 Previously Unavailable Researched, written, curated & edited by: James Hurman, Principal, Previously Unavailable Acknowledgements: My huge thanks to all 52 of the people who generously gave their time to be part of this study. To Paul Dykzeul of Bauer Media who gave me access to Bauer’s panel of readers to complete the survey on Auckland pride and to Tanya Walshe, also of Bauer Media, who organised and debriefed the survey. To Jane Sweeney of Anthem who connected me with many of the people in this study and extremely kindly provided me with the desk upon which this document has been created. To the people at ATEED, Cooper & Company and Cheshire Architects who provided the photos. And to Dick Frizzell who donated his time and artistic eforts to draw his brilliant caricature of a New Aucklander. You’re all awesome. Thank you. Photo Credits: p.14 – Basketballers at Wynyard – Derrick Coetzee p.14 – Britomart signpost – Russell Street p.19 - Auckland from above - Robert Linsdell p.20 – Lantern Festival food stall – Russell Street p.20 – Art Exhibition – Big Blue Ocean p.40 – Auckland Museum – Adam Selwood p.40 – Diner Sign – Abaconda Management Group p.52 – Lorde – Constanza CH SOMETHING’S UP IN AUCKLAND “We had this chance that came up in Hawkes Bay – this land, two acres, right on the beach. -

Kalamazoo River Draft Supplemental Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment

Kalamazoo River Draft Supplemental Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment Prepared by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy Michigan Department of Natural Resources Michigan Department of Attorney General April 2021 Regulatory Notes An Environmental Assessment is prepared to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA). The NEPA is the Nation’s premier environmental law that guarantees every American the right to review, comment, and participate in planning of federal decisions that may affect the human environment. The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) on July 16, 2020 issued in the Federal Register a final rule updating its regulations for the NEPA (85 Fed. Reg. 43304, July 16, 2020). On January 20, 2021, President Joseph R. Biden issued an Executive Order entitled “Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis” that requires agencies to immediately review promulgation of Federal regulations and other actions during the previous four years to determine consistency with Section 1 of the Executive Order. This may include the CEQ reviewing the July 16, 2020 update to the NEPA regulations. The goals of the July 2020 amendments to the NEPA regulations were to reduce paperwork and delays and to promote better decisions consistent with the policy set forth in section 101 of the NEPA. The effective date of these amended regulations was September 14, 2020. However, for actions that began before September 14th, such as this one, agencies may continue with the regulations in effect before September 14th because applying the amended regulations would cause delays to the ongoing process.