Louise Simone Armshaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

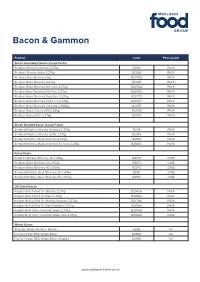

Bacon & Gammon

Bacon & Gammon Product Code Pricing Unit Sliced Unsmoked Bacon (Large Packs) Rindless Streaky Stirchley 2.27kg B203 PACK Rindless Streaky Selfar 2.27kg B203S PACK Rindless Back Stirchley 2kg B207D2 PACK Rindless Back Stirchley 2.27kg B207D PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Dry Cure 2.27kg B207DA PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Rib Free 2.27kg B207DR PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Supertrim 2.27kg B207ST PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Thick Cut 2.27kg B207DT PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Catering 2.268kg B207E PACK Rindless Back Classic (A11) 2.25kg B207M PACK Rindless Back Selfar 2.27kg B207S PACK Sliced Smoked Bacon (Large Packs) Smoked Rindless Streaky Stirchley 2.27kg B204 PACK Smoked Rindless Streaky Selfar 2.27kg B204S PACK Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 2.27kg B218D PACK Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley Dry Cure 2.27kg B218DC PACK Retail Packs Rindless Streaky Stirchley 20 x 454g B2031 CASE Rindless Back Stirchley 20 x 454g B2071 CASE Rindless Back Stirchley 40 x 200g B207C CASE Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 20 x 454g B2181 CASE Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 40 x 200g B218C CASE UK Sliced Bacon Knights British Rind On Streaky 2.27kg B206UK PACK Knights British Rind On Back 2.27kg B208UK PACK Knights British Rind On Streaky Smoked 2.27kg B217UK PACK Knights British Rind On Back Smoked 2.27kg B219UK PACK Knights British Dry Cured R/L Back 2.27kg B207UD PACK Knights British Dry Cured R/L Back Smk 2.27kg B218UD PACK Whole Bacon Stirchley Whole Rindless Streaks B258 KG Danish Crown BSD Whole Backs B255D KG Danish Crown BSD Whole Backs Smoked B259D -

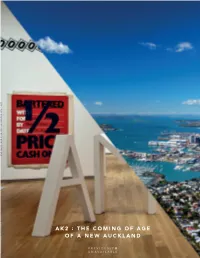

Ak2 : the Coming of Age of a New Auckland

AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE A NEW AUCKLAND PREVIOUSLY UNAVAILABLE PREVIOUSLY AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE OF A NEW AUCKLAND AK2: The Coming of Age of a New Auckland Published June 2014 by: Previously Unavailable www.previously.co [email protected] © 2014 Previously Unavailable Researched, written, curated & edited by: James Hurman, Principal, Previously Unavailable Acknowledgements: My huge thanks to all 52 of the people who generously gave their time to be part of this study. To Paul Dykzeul of Bauer Media who gave me access to Bauer’s panel of readers to complete the survey on Auckland pride and to Tanya Walshe, also of Bauer Media, who organised and debriefed the survey. To Jane Sweeney of Anthem who connected me with many of the people in this study and extremely kindly provided me with the desk upon which this document has been created. To the people at ATEED, Cooper & Company and Cheshire Architects who provided the photos. And to Dick Frizzell who donated his time and artistic eforts to draw his brilliant caricature of a New Aucklander. You’re all awesome. Thank you. Photo Credits: p.14 – Basketballers at Wynyard – Derrick Coetzee p.14 – Britomart signpost – Russell Street p.19 - Auckland from above - Robert Linsdell p.20 – Lantern Festival food stall – Russell Street p.20 – Art Exhibition – Big Blue Ocean p.40 – Auckland Museum – Adam Selwood p.40 – Diner Sign – Abaconda Management Group p.52 – Lorde – Constanza CH SOMETHING’S UP IN AUCKLAND “We had this chance that came up in Hawkes Bay – this land, two acres, right on the beach. -

B Spec. LI) 571 3467 N M 1958

‘■ri •' ’>-. • v ' • •>;*;..;.':\.;’sv: v • ^vy\ Sf :'-y,!\ •■.'’■’• •';-t'-. •• •;;‘ ^ ■•'•'; * v; • .; •": ••• ■ ■•■•’.. •.. • ■•■ .: ‘ V'.' •*•*' •" " ,;.v : v : • 1 ' KVd ' 5; Si'; -'4 \r b ; :■ 31 If ■ £ i K-: ; 1: ! ’ ,4 m| . -i Lij Kr< :f • S-- fee - a S? f: ? ■ •. ■ 'vi ,v; ■i i’ - jWJv i .• ■ 1 I' /- /•• >: . r ■ :.y •V 14 fe ggc£;;;.' - ;:' . JVS :vo,’vf '•\X -ySKft I! V v L:V ■"'M msmB . • : "'f/'el r?*l '. :■$ : ;I ; - Spec. 1 LI) 1 W- 571 f > . - •--- 1 •- '«’• ■ ■ ............ ■ • " • r1 r-s-v” vi/ 7X 3467 istarian: - w V/ ‘ .*« •v .. -:.v Wi .TJ- p: J:- fi, •; n ; W5 M 1958 •• ,'v*7 ’ '•‘,'*'^A>: >r,A >£V _ : .. :.■:>• • *J' Mirvw'-v*; ; >1 ■■ ,--> ... .. Bf **>■ .• >. 1 * - ,«■ l.. 1 I £ * : 4 f 4 n € iI »v3 £i % 58 i* 4 Wistarian I I -• 3-: «> '« *, I * < «s *c = = = 2 Al Spec! liD 57 I 15 %7 University of Bridgeport Bridgeport, Connecticut 1958 Staff Judith M. Carr ....... ........Co-Editor Charles S. Huestis ._ ........Co-Editor Robert W. Stumpek Lay-Out Editor Dr. John Benz ....... ............Advisor 67043 i I ■ Dedication * The University of Bridgeport has changed considerably from the two-campus univer sity it was at its incorporation in 194 7. We have grown in more ways than one — in fact, growth has been the key wore in all areas. Physically, UB has built or rerr. deled several major campus buildings since In that year, Fones Hall was built; i 1 1950, the Engineering-Technology Building; in 1953, Alumni Hall was remodeled from a private home; in 1955, the Drama Center and Carlson Library were built; in 1956, the gymnasium; and in 1957, the two dormitor ies and dining hall. -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester R M Johnson Phd 2020

Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester R M Johnson PhD 2020 Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester RACHEL MARGARET JOHNSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by Manchester Metropolitan University 2020 Abstract My dissertation demonstrates how a new and distinctive musical culture developed in the industrialising society of early Victorian Manchester. It challenges a number of existing narratives relating to the history of music in nineteenth-century Britain, and has implications for the way we understand the place of music in other industrial societies and cities. The project is located at the nexus between musicology, cultural history and social history, and draws upon ideas current in urban studies, ethnomusicology and anthropology. Contrary to the oft-repeated claim that it was Charles Hallé who ‘brought music to Manchester’ when he arrived in 1848, my archival research reveals a vast quantity and variety of music-making and consumption in Manchester in the 1830s and 1840s. The interconnectedness of the many strands of this musical culture is inescapable, and it results in my adoption of ‘networks’ as an organising principle. Tracing how the networks were formed, developed and intertwined reveals just how embedded music was in the region’s social and civic life. Ultimately, music emerges as an agent of particular power in the negotiation and transformation of the concerns inherent within the new industrial city. The dissertation is structured as a series of interconnected case studies, exploring areas as diverse as the music profession, glee and catch clubs, the Hargreaves Choral Society’s programme notes, Mechanics’ Institutions and the early Victorian public music lecture. -

Chapter One James Mylne: Early Life and Education

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. 2013 THESIS Rational Piety and Social Reform in Glasgow: The Life, Philosophy and Political Economy of James Mylne (1757-1839) By Stephen Cowley The University of Edinburgh For the degree of PhD © Stephen Cowley 2013 SOME QUOTES FROM JAMES MYLNE’S LECTURES “I have no objection to common sense, as long as it does not hinder investigation.” Lectures on Intellectual Philosophy “Hope never deserts the children of sorrow.” Lectures on the Existence and Attributes of God “The great mine from which all wealth is drawn is the intellect of man.” Lectures on Political Economy Page 2 Page 3 INFORMATION FOR EXAMINERS In addition to the thesis itself, I submit (a) transcriptions of four sets of student notes of Mylne’s lectures on moral philosophy; (b) one set of notes on political economy; and (c) collation of lectures on intellectual philosophy (i.e. -

A History Manchester College

A HISTORY MANCHESTER COLLEGE A HISTORY OF MANCHESTER COLLEGE FROM ITS FOUNDATION IN MANCHESTER TO ITS ESTABLISHMENT IN OXFORD 4.Y V. D. DAVIS, B.A. LONDON GEORGE ALLEN 6' UNWIN LTD MANCHESTER COLLEGE, OXFORD Entrance under the Tower MUSEUM STREET FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1932 k?. -< C-? . PREFACE k THISrecord of the history of Manchester College has been - prepared at the instance of the College Committee, and is E published on their responsibility and at their sole cost. It is based upon ample material provided by the long series :' of annual reports and the seventeen large folio volumes Y- F'$2 of the minutes of the Committee, and further volumes of collected College documents, together with two volumes of the minutes of the Warrington Academy. Much information . of historical value has been gathered from the published addresses of Principals and other members of the Teaching Staff, and the Visitors. The record is also greatly indebted to Dr. Drummond's Life aad Letters of james A4artineau, and other memoirs of College teachers and distinguished students, to which reference will be found in the notes. a It has been a great privilege to an old student of the College, whose father also was a student both at York and Manchester, to be allowed to undertake this work, in which he received encouragement and invaluable help from two other elder friends and old students, Dr. Edwin Odgers and Alexander Gordon. To their memory, as to that of his own revered and beloved teachers in the College, Martineau, Drummond, Upton, Carpenter, he would have desired, had it been worthy, humbly and gratefully to dedicate his work. -

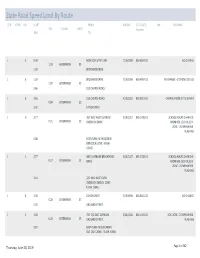

State Road Speed Limit by Route RTE TEMP DIR

State Road Speed Limit By Route RTE TEMP DIR. START FROM APPRVD STC / OSTA SM REMARKS DIST TOWN SPEED Number END TO 1 B0.00 NEW YORK STATE LINE 7/19/1990 056‐9004‐03 NO CHANGE 1.59 GREENWICH 35 1.59 BROOKSIDE DRIVE 1 B1.59 BROOKSIDE DRIVE 7/19/1990 056‐9004‐03 NO CHANGE ‐ STC# 056‐0201‐03 1.07 GREENWICH 30 2.66 OLD CHURCH ROAD 1 B2.66 OLD CHURCH ROAD 4/16/2002 056‐0201‐03 CHANGE FROM 35 TO 30 MPH 0.84 GREENWICH 30 3.50 TAYLOR DRIVE 1 N2.77 350' W/O WEST CURBLINE 9/14/2017 056‐1708‐01 SCHOOL HOURS CHANGED 0.31 GREENWICH 25 OVERLOOK DRIVE FROM 056‐1509‐01;SCH. ZONE ‐ 25 MPH WHEN FLASHING 3.08 EAST CURBLINE WOODSIDE DRIVE(SCH. ZONE ‐ FLASH. SIGNS) 1 S2.77 WEST CURBLINE BROOKRIDGE 9/14/2017 056‐1708‐01 SCHOOL HOURS CHANGED 0.37 GREENWICH 25 DRIVE FROM 056‐1509‐01;SCH. ZONE ‐ 25 MPH WHEN FLASHING 3.14 325' W/O WEST CURB OVERLOOK DR(SCH. ZONE‐ FLASH. SIGN) 1 B3.50 TAYLOR DRIVE 7/19/1990 056‐9004‐03 NO CHANGE 0.28 GREENWICH 30 3.78 ORCHARD STREET 1 S3.66 720' E/O EAST CURBLINE 2/26/2016 056‐1509‐02 SCH. ZONE ‐ 25 MPH WHEN 0.26 GREENWICH 25 ORCHARD STREET FLASHING 3.92 EAST CURBLINE SUBURBAN AVE. (SCH. ZONE ‐ FLASH. SIGN) Thursday, June 20, 2019 Page 1 of 282 RTE TEMP DIR. START FROM APPRVD STC / OSTA SM REMARKS DIST TOWN SPEED Number END TO 1 N3.66 70' W/O WEST CURBLINE 2/26/2016 056‐1509‐02 SCH. -

1934 Unitarian Movement.Pdf

fi * " >, -,$a a ri 7 'I * as- h1in-g & t!estP; ton BrLLnch," LONDON t,. GEORGE ALLEN &' UNWIN- LID v- ' MUSEUM STREET FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1934 ACE * i& ITwas by invitation of The Hibbert Trustees, to whom all interested in "Christianity in its most simple and intel- indebted, that what follows lieibleV form" have long been was written. For the opinions expressed the writer alone is responsible. His aim has been to give some account of the work during two centuries of a small group of religious thinkers, who, for the most part, have been overlooked in the records of English religious life, and so rescue from obscurity a few names that deserve to be remembered amongst pioneers and pathfinders in more fields than one. Obligations are gratefully acknowledged to the Rev. V. D. Davis. B.A., and the Rev. W. H. Burgess, M.A., for a few fruitful suggestions, and to the Rev. W. Whitaker, I M.A., for his labours in correcting proofs. MANCHESTER October 14, 1933 At1 yigifs ~ese~vcd 1L' PRENTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY UNWIN BROTHERS LTD., WOKING CON TENTS A 7.. I. BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP' PAGE BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP 1 3 iI. EDUCATION CONFORMIST ACADEMIES 111. THE MODERN UNIVERSITIES 111. JOURNALS AND WRIODICAL LITERATURE . THE UNITARIAN CONTRIBUTI:ON TO PERIODICAL . LITERATURE ?aEz . AND BIOGR AND BELLES-LETTRES 11. PHILOSOPHY 111. HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY I IV. LITERATURE ....:'. INDEX OF PERIODICALS "INDEX OF PERSONS p - INDEX OF PLACES :>$ ';: GENERAL INDEX C. A* - CHAPTER l BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP 9L * KING of the origin of Unitarian Christianity in this country, -

By Geoffrey Head, BA

John Relly Beard Lecture 1997 by Geoffrey Head, BA Sponsored by The Ministerial Fellowship General Assembly of Unitarian & Free Christian Churches eter Eckersley, Secretary of the Unitarian congregation at Dawson's Croft in Salford, awoke one morning in February 1825, conscious that he had an important letter to write. He had been directed to head hunt a Minister. In those days there was no General Assembly, no District Associations in the present day sense, there were no 'Guide Lines for the Ministry'; even the British and Foreign Unitarian Association was only in the process of formation. Doubtless the Unitarian grapevine worked as insidiously as it does today, but there were certainly no vacant pulpit lists. To add to Mr Eckersley's difficulties, he had the task of addressing a student at Manchester College, York - a student who stood out, even amongst such illustrious contemporaries as James Martineau, John James Tayler and Robert Aspland, for academic ability and missionary enthusiasm. The congregation at Greengate had not much to offer. It had, on the previous Christmas Day, opened its first modest building, but it was a poor and struggling cause in a working class area on the wrong side of the River Irwell, even though it had the benevolent interest and support of a number of grandees from the wealthy and prominent Cross Street congregation less than one mile away. he student being head hunted, John Relly Beard, could well have had a choice of more prominent pulpits. The congregation stretched itself to offer a stipend of £ 120 p.a., probably with the help of such Cross Street worthies as Sir Thomas Potter, later to becorn; first Mayor of Manchester, and Richard Potter, elected M.P. -

List of Prominent UU's from UUA Site at “Web

List of prominent UU’s from UUA site at www.uua.org/uuhs/duub/ “web” means biography is on web site. 1 A Bela Bartok(1881-1945) web Matthew Caffyn, (1628-1714) Abiel Abbot (1765-1859) Cyrus Augustus Bartol (1813-1900) John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) web Francis Ellingwood Abbot (1836-1903) Clara Barton (1821-1912) Lon Ray Call (1894-1985) John Emery Abbot (1793-1819) Seth Curtis Beach (1839-1932) Calthrop, Samuel Robert (1829-1917) John Abernethy (1680-1740) web Charles Beard (1827-1888) Angus Cameron(1913-1996) web William Adam (1796-1881) web John Relly Beard (1800-1876) web Geoffrey Campbell Abigail Adams (1744-1818) web Jeremy Belknap (1744-1798) Ida Maud Cannon (1877-1960) Charles Francis Adams (1807-1886) Henry Whitney Bellows (1814-1882) Norbert Capek(1870-1942) web Hannah Adams (1755-1831) web Thomas Belsham (1750-1829) Julia Fletcher Carney (1823-1908) Henry Adams (1838-1918) Margret Jonsdottir Benedictsson (1866-1956) James Estlin Carpenter (1844-1927) James Luther Adams(1901-1994) web Georges de Benneville (1703-1793) Lant Carpenter (1780-1840) John Adams (1735-1826) web Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) Mary Carpenter (1807-1877) John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) web Henry Bergh (1811-1880) Sara Pratt Carr (1850-1935) Marian Hooper Adams (1843-1885) Giorgio Biandrata (16th cent) William Herbert Carruth(1859-1924) Sarah Flower Adams (1805-1848) John Biddle (1616-1662) Alice Cary (1820-1871) web Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz (1822-1907) Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914) Henry Montfort Cary (1878-1936) Conrad Aiken (1889-1973) Mary Billings Maude Simonton Cary (1878-1937) Lucy Aikin (1781-1861) Herman Bisbee (1833-1879) Phoebe Cary (1824-1871) web Thomas Aikenhead (1676-1698) web Antoinette Louisa Brown Blackwell (1825- Sebastian Castellio (1515-1563) Bronson Alcott (1799-1888) 1921) Mary Hartwell Catherwood (1847-1902) Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) web Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910) Carrie Clinton Lane Chapman Catt (1859- Horatio Alger, Jr. -

General Histories

GENERAL HISTORIES Allen, Joseph Henry An historical sketch of the Unitarian movement since the reformation (New York, 1894) ["The only work in English attempting to cover the entire field was [c.1905] in fact only a 'sketch' hastily done and with little use of primary sources" (E. M. Wilbur History 1 p.vii)] Beard, John Relly, Unitarianism exhibited in its actual condition: consisting of essays by several Unitarian ministers and others; illustrative of the rise, progress, and principles of Christian anti-trinitarianism in different parts of the world (London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co, 1846) Burgess, Walter H. 'Work in the field of Unitarian history' TUHS 1:1 (1916) 1-10 Carpenter, Joseph Unitarianism, an Historic Survey London (1922) [reprinted from The Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics ] Cooke, George Willis Unitarianism: its origin and history (Boston, American Unitarian Association, 1890) ["a series of popular lectures by different persons, wholly done at second hand" (E. M. Wilbur History 1 p.vii)] Fock, Otto Der Socinianismus: nach seiner Stellung in der Gesammtentwicklung des christlichen Geistes, nach seinem historischen Verlauf und nach seinem Lehrbegriff (Kiel, Carl Schröder, 1847) (Can be read online as a Google eBook by those with a knowledge of German) Gordon, Alexander 'Unitarianism' Encyclopedia Britannica (11th edition, 1911) Harris, George ‘List of Unitarian congregations in 1819’ Christian Life 6 January 1894 [copy in W H Burgess’s Scrapbook p. 75 Burgess Mss D19] Hill, Andrew McKean A Liberal Religious Heritage: Unitarian