Adventures in the Fish Trade*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi

Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 (http://www.accessscience.com/) Article by: Boschung, Herbert Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Gardiner, Brian Linnean Society of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, United Kingdom. Publication year: 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400) Content Morphology Euteleostei Bibliography Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi The most recent group of actinopterygians (rayfin fishes), first appearing in the Upper Triassic (Fig. 1). About 26,840 species are contained within the Teleostei, accounting for more than half of all living vertebrates and over 96% of all living fishes. Teleosts comprise 517 families, of which 69 are extinct, leaving 448 extant families; of these, about 43% have no fossil record. See also: Actinopterygii (/content/actinopterygii/009100); Osteichthyes (/content/osteichthyes/478500) Fig. 1 Cladogram showing the relationships of the extant teleosts with the other extant actinopterygians. (J. S. Nelson, Fishes of the World, 4th ed., Wiley, New York, 2006) 1 of 9 10/7/2015 1:07 PM Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 Morphology Much of the evidence for teleost monophyly (evolving from a common ancestral form) and relationships comes from the caudal skeleton and concomitant acquisition of a homocercal tail (upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin are symmetrical). This type of tail primitively results from an ontogenetic fusion of centra (bodies of vertebrae) and the possession of paired bracing bones located bilaterally along the dorsal region of the caudal skeleton, derived ontogenetically from the neural arches (uroneurals) of the ural (tail) centra. -

Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean Volume

ISBN 0-9689167-4-x Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean (Davis Strait, Southern Greenland and Flemish Cap to Cape Hatteras) Volume One Acipenseriformes through Syngnathiformes Michael P. Fahay ii Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean iii Dedication This monograph is dedicated to those highly skilled larval fish illustrators whose talents and efforts have greatly facilitated the study of fish ontogeny. The works of many of those fine illustrators grace these pages. iv Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean v Preface The contents of this monograph are a revision and update of an earlier atlas describing the eggs and larvae of western Atlantic marine fishes occurring between the Scotian Shelf and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Fahay, 1983). The three-fold increase in the total num- ber of species covered in the current compilation is the result of both a larger study area and a recent increase in published ontogenetic studies of fishes by many authors and students of the morphology of early stages of marine fishes. It is a tribute to the efforts of those authors that the ontogeny of greater than 70% of species known from the western North Atlantic Ocean is now well described. Michael Fahay 241 Sabino Road West Bath, Maine 04530 U.S.A. vi Acknowledgements I greatly appreciate the help provided by a number of very knowledgeable friends and colleagues dur- ing the preparation of this monograph. Jon Hare undertook a painstakingly critical review of the entire monograph, corrected omissions, inconsistencies, and errors of fact, and made suggestions which markedly improved its organization and presentation. -

A New Species of Cretaceous Acanthomorph from Canada 15 February 2016, by Sarah Gibson

A new species of Cretaceous acanthomorph from Canada 15 February 2016, by Sarah Gibson to sit flush along the body, helping the fish swim faster by reducing drag, or they can be extended completely out to act as a defense mechanism, in case you are a predator looking for a quick bite. Near the base of the Acanthomorpha phylogenetic tree is a small group of fishes, Polymixiiformes, comprised of a single living genus, Polymixia, more commonly known as the beardfish. This innocuous fish seems harmless, but according to many ichthyologists, Polymixia is just one key to understanding acanthomorph relationships. Unraveling the evolutionary relationships is difficult with a single living genus, but thankfully, polymixiiforms have a fossil record dating back to the Cretaceous, containing an increasing number of taxa as new discoveries are being made, particularly in deposits in North America, where fewer acanthomorph fossils are known compared to Figuring out fish relationships is no small feat. Credit: the more-studied Eastern Tethys Ocean deposits in Near et al. 2013 Europe. For being one of the largest groups of vertebrates, and having one of the richer fossil records among organisms, the relationships of fishes are still hotly debated. Humongous datasets are being compiled that involve molecular (both nuclear and mitochondrial) data, compared and contrasted with thorough morphological analyses. (I'm not going to get into all of it here, simply because of its sheer complexity.) What I am going to get into, however, is the fossil record of one subset of fishes, the acanthomorphs. The stout beardfish, Polymixia nobilis. Credit: Wikipedia Acanthomorphs are teleost fishes that possess true fin spines: a set of prominent, sharp, unsegmented spines in the front portion of their dorsal and/or anal fins, followed by a portion of One such new species was recently described by pliable, segmented, "softer" looking rays. -

Distinguishing Drift and Selection Empirically: “The Great Snail Debate” of the 1950S

Distinguishing Drift and Selection Empirically: “The Great Snail Debate” of the 1950s ROBERTA L. MILLSTEIN Department of Philosophy University of California, Davis One Shields Avenue Davis, CA 95616 USA E-mail: [email protected] Forthcoming in the Journal of the History of Biology -- no doubt, there will be some (hopefully small) changes in the proofing process Distinguishing Drift and Selection Empirically p. 1 Abstract: Biologists and philosophers have been extremely pessimistic about the possibility of demonstrating random drift in nature, particularly when it comes to distinguishing random drift from natural selection. However, examination of a historical case - Maxime Lamotte's study of natural populations of the land snail, Cepaea nemoralis in the 1950s - shows that while some pessimism is warranted, it has been overstated. Indeed, by describing a unique signature for drift and showing that this signature obtained in the populations under study, Lamotte was able to make a good case for a significant role for drift. It may be difficult to disentangle the causes of drift and selection acting in a population, but it is not (always) impossible. Keywords: adaptationism, Arthur J. Cain, conspicuous polymorphism, Cepaea nemoralis, random genetic drift, ecological genetics, evolution, Philip M. Sheppard, Maxime Lamotte, natural selection, selectionist Pessimistic Introduction The process known as “random drift”1 is often considered to be one of the most important chance elements in evolution. Yet, over the years, biologists and philosophers have expressed pessimism about the possibility of demonstrating random drift in nature. The following is just a sampling. In 1951, Arthur Cain argued: 1 Authors refer to this phenomenon variously as “random drift,” “genetic drift,” “random genetic drift,” or simply “drift,” without any apparent shift in meaning. -

Lab 9 - an Introduction to Marine Fishes

Name ___________________________________ Lab 9 - An introduction to marine fishes NOTE: these taxonomic groups have many more species than those shown today; each specimen is but a representative of its particular family or order. PLEASE HANDLE SPECIMENS CAREFULLY!!!! Superclass Agnatha (jawless fishes; ~80 spp.) Class Myxini Order Myxiniformes Family Myxinidae; Hagfish (Myxine glutinosa) Class Cephalaspidomorphi Order Petromyzontiformes Family Petromyzontidae; Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) 1) What are some key differences between Myxinids and Petromyzontids? Superclass Gnathostomata (jawed fishes) Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes) Subclass Elasmobranchii (shark-like fishes; 800 spp) Order Squatiniformes; Angel shark (Squatina dumerili) Order Squaliformes; Spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) Order Rajiformes; Clearnose skate (Raja eglanteria), Guitarfish (Rhinobatos sp.) Subclass Holocephali (chimaeras; 30 spp) Order Chimaeriformes; Spotted chimaera (Hydrolagus colliei) 2) What are two features that clearly distinguish the order Rajiformes (skates) from sharks? 3) Where in the water column would you expect to find a chimaera? Why? Class Teleostomi (bony fishes) Superorder Clupeomorpha Order Clupeiformes Family Clupeidae; Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus), Menhaden (Brevoortia tyrannus) Family Engraulidae; Anchovy (Anchoa nasuta) 4) What characteristics most clearly separate these two families? 5) These fishes tend to travel in schools. What purpose might the silvery stripe down their sides serve? (Hint: think about this from -

Percomorph Phylogeny: a Survey of Acanthomorphs and a New Proposal

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 52(1): 554-626, 1993 PERCOMORPH PHYLOGENY: A SURVEY OF ACANTHOMORPHS AND A NEW PROPOSAL G. David Johnson and Colin Patterson ABSTRACT The interrelationships of acanthomorph fishes are reviewed. We recognize seven mono- phyletic terminal taxa among acanthomorphs: Lampridiformes, Polymixiiformes, Paracan- thopterygii, Stephanoberyciformes, Beryciformes, Zeiformes, and a new taxon named Smeg- mamorpha. The Percomorpha, as currently constituted, are polyphyletic, and the Perciformes are probably paraphyletic. The smegmamorphs comprise five subgroups: Synbranchiformes (Synbranchoidei and Mastacembeloidei), Mugilomorpha (Mugiloidei), Elassomatidae (Elas- soma), Gasterosteiformes, and Atherinomorpha. Monophyly of Lampridiformes is justified elsewhere; we have found no new characters to substantiate the monophyly of Polymixi- iformes (which is not in doubt) or Paracanthopterygii. Stephanoberyciformes uniquely share a modification of the extrascapular, and Beryciformes a modification of the anterior part of the supraorbital and infraorbital sensory canals, here named Jakubowski's organ. Our Zei- formes excludes the Caproidae, and characters are proposed to justify the monophyly of the group in that restricted sense. The Smegmamorpha are thought to be monophyletic principally because of the configuration of the first vertebra and its intermuscular bone. Within the Smegmamorpha, the Atherinomorpha and Mugilomorpha are shown to be monophyletic elsewhere. Our Gasterosteiformes includes the syngnathoids and the Pegasiformes -

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

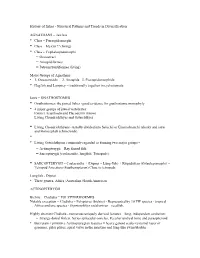

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

18 Special Habitats and Special Adaptations 395

THE DIVERSITY OF FISHES Dedications: To our parents, for their encouragement of our nascent interest in things biological; To our wives – Judy, Sara, Janice, and RuthEllen – for their patience and understanding during the production of this volume; And to students and lovers of fishes for their efforts toward preserving biodiversity for future generations. Front cover photo: A Leafy Sea Dragon, Phycodurus eques, South Australia. Well camouflaged in their natural, heavily vegetated habitat, Leafy Sea Dragons are closely related to seahorses (Gasterosteiformes: Syngnathidae). “Leafies” are protected by Australian and international law because of their limited distribution, rarity, and popularity in the aquarium trade. Legal collection is highly regulated, limited to one “pregnant” male per year. See Chapters 15, 21, and 26. Photo by D. Hall, www.seaphotos.com. Back cover photos (from top to bottom): A school of Blackfin Barracuda, Sphyraena qenie (Perciformes, Sphyraenidae). Most of the 21 species of barracuda occur in schools, highlighting the observation that predatory as well as prey fishes form aggregations (Chapters 19, 20, 22). Blackfins grow to about 1 m length, display the silvery coloration typical of water column dwellers, and are frequently encountered by divers around Indo-Pacific reefs. Barracudas are fast-start predators (Chapter 8), and the pan-tropical Great Barracuda, Sphyraena barracuda, frequently causes ciguatera fish poisoning among humans (Chapter 25). Longhorn Cowfish, Lactoria cornuta (Tetraodontiformes: Ostraciidae), Papua New Guinea. Slow moving and seemingly awkwardly shaped, the pattern of flattened, curved, and angular trunk areas made possible by the rigid dermal covering provides remarkable lift and stability (Chapter 8). A Silvertip Shark, Carcharhinus albimarginatus (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae), with a Sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates, Perciformes: Echeneidae) attached. -

The Phylogenetic Relationships of Lampridiform Fishes (Teleostei: Acanthomorpha), Based on a Total-Evidence Analysis of Morphological and Molecular Data E

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Vol. 10, No. 3, December, pp. 417–425, 1998 ARTICLE NO. FY980532 The Phylogenetic Relationships of Lampridiform Fishes (Teleostei: Acanthomorpha), Based on a Total-Evidence Analysis of Morphological and Molecular Data E. O. Wiley,*,† G. David Johnson,† and Walter Wheaton Dimmick* *Natural History Museum and Department of Systematics and Ecology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045; and †Division of Fishes, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20560 Received November 11, 1997; revised March 10, 1998 The Lampridiformes comprise 21 species in 12 gen- We investigated the phylogenetic relationships era and 7 families. The relatively small (40 cm) velifer- among five species of lampridiform fishes, three basal ids and much larger (1.8 m) opahs (Lamprididae) are outgroup species (two aulopiforms and one myctophi- deep bodied. The remaining families are elongate and form), and two species of non-lampridiform acantho- range in body size from the small tube-eyes (Stylephori- morphs (Polymixia and Percopsis) using a combined dae, 31 cm) to the very large Regalecus (17 m). All but parsimony analysis of morphological and molecular the near shore veliferids are oceanic fishes, ranging data. Morphological characters included 28 transfor- mation series obtained from the literature. Molecular from the epipelagic realm to abyssal depths. Lampridi- characters included 223 informative transformation form fishes are characterized by a uniquely protusible series from an aligned 854-base pair fragment of 12S upper jaw apparatus and have been considered a mtDNA and 139 informative transformation series from natural group since Regan (1907) named them. Prior to an aligned 561-base pair fragment of 16S mtDNA. -

Divining Darwin: Evolving Responses and the Contribution of David Lack1

S & CB (2014), 26, 53–78 0954–4194 R. J. (SAM) BERRY Divining Darwin: Evolving Responses and the Contribution of David Lack1 Christian believers, particularly evangelicals, often react to evolutionary ideas with more heat than light. A significant contribution to clarifying understanding was a book published in 1957, Evolutionary Theory and Christian Belief by the eminent ornithologist David Lack. It was the first attempt to tease out the issues by a scientist of his calibre. Information about this book has recently been published in a biography of Lack. This essay seeks to put Lack’s contribution into the perspective of both past and continuing perceptions of Christianity and evolution. Key words: Darwin, Darwinism, Evolutionary Theory and Christian Belief, David Lack, Dan and Mary Neylan, C.S.Lewis, human nature, imago Dei This paper is about the contribution of David Lack, one of the most dis- tinguished biologists of the twentieth century, to the debates about evolu- tion and Christianity, and his personal journey thereto. His contribution is significant because of the authority he brought to a book he wrote in 1957, which raised these debates to a much more positive and informed level than had previously been the practice. But before we get to Lack and his book, we need to understand something of the background to the understanding of evolution by both scientists and Christians. The reaction of the Christian community to Darwin’s Origin of Species2 ought to be a simple matter of historical record.3 In practice it is regularly muddied. An Editorial in Nature in 2009 claimed, ‘In England the Church reacted badly to Darwin’s theory, going so far as to say that to believe it was to imperil your soul.’4 There may well have been those who maintained this, but they seem to have been few. -

Euteleostei: Aulopiformes) and the Timing of Deep-Sea Adaptations ⇑ Matthew P

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57 (2010) 1194–1208 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Estimating divergence times of lizardfishes and their allies (Euteleostei: Aulopiformes) and the timing of deep-sea adaptations ⇑ Matthew P. Davis a, , Christopher Fielitz b a Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, 119 Foster Hall, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA b Department of Biology, Emory & Henry College, Emory, VA 24327, USA article info abstract Article history: The divergence times of lizardfishes (Euteleostei: Aulopiformes) are estimated utilizing a Bayesian Received 18 May 2010 approach in combination with knowledge of the fossil record of teleosts and a taxonomic review of fossil Revised 1 September 2010 aulopiform taxa. These results are integrated with a study of character evolution regarding deep-sea evo- Accepted 7 September 2010 lutionary adaptations in the clade, including simultaneous hermaphroditism and tubular eyes. Diver- Available online 18 September 2010 gence time estimations recover that the stem species of the lizardfishes arose during the Early Cretaceous/Late Jurassic in a marine environment with separate sexes, and laterally directed, round eyes. Keywords: Tubular eyes have arisen independently at different times in three deep-sea pelagic predatory aulopiform Phylogenetics lineages. Simultaneous hermaphroditism evolved a single time in the stem species of the suborder Character evolution Deep-sea Alepisauroidei, the clade of deep-sea aulopiforms during the Early Cretaceous. This result indicates the Euteleostei oldest known evolutionary event of simultaneous hermaphroditism in vertebrates, with the Alepisauroidei Hermaphroditism being the largest vertebrate clade with this reproductive strategy. Divergence times Ó 2010 Elsevier Inc. -

Cain on Linnaeus: the Scientist-Historian As Unanalysed Entity

Stud. Hist. Phil. Biol. & Biomed. Sci., Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 239–254, 2001 Pergamon 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain 1369-8486/01 $ - see front matter www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc Cain on Linnaeus: The Scientist-Historian as Unanalysed Entity Mary P. Winsor* Zoologist A. J. Cain began historical research on Linnaeus in 1956 in connection with his dissatisfaction over the standard taxonomic hierarchy and the rules of binomial nomenclature. His famous 1958 paper ‘Logic and Memory in Linnaeus’s System of Taxonomy’ argues that Linnaeus was following Aristotle’s method of logical division without appreciating that it properly applies only to ‘analysed entities’ such as geo- metric figures whose essential nature is already fully known. The essence of living things being unanalysed, there is no basis on which to choose the right characters to define a genus nor on which to differentiate species. Yet Cain’s understanding of Aristotle, which depended on a 1916 text by H. W. B. Joseph, was fatally flawed. In the 1990s Cain devoted himself to further historical study and softened his verdict on Linnaeus, praising his empiricism. The idea that Linnaeus was applying an ancient and inappropriate method cries out for fresh study and revision. 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: A. J. Cain; Linnaeus; Aristotle; Essentialism; Systematics; Logic. The category to which the following belongs is not the history of systematics but the history of the history of systematics. I have just one small tale to tell, but I suspect there are similar tales scattered about unnoticed in the history of other sciences, and it seems to me they are worth uncovering.