WIDER Working Paper 2014/023 Aid and Policy Preference in Oil-Rich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy in Indonesia

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1994-06 Democracy in Indonesia Kusmayati, Anne Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/28094 DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY CA 93943-5101 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Democracy In Indonesia by Anne JKusmayati Civilian Staff, Indonesian Department of Defense Engineering in Community Nutrition and Family Resources, Bogor Agricultural University, 1983. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN INTERNATIONAL RESOURCE PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT from the NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL June, 1994 David R. Wfiipple, Jr.,j£hairman REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204. Arlington. VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 1994. Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA 6. AUTHOR(S): Anne Kusmayati 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION Monterey CA 93943-5000 REPORT NUMBER SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

General Nasution Brig.Jen Sarwo Edhie Let.Gen Kemal Idris Gen

30 General Nasution Brig.Jen Sarwo Edhie Let.Gen Kemal Idris Gen Simatupang Lt Gen Mokoginta Brig Jen Sukendro Let.Gen Mokoginta Ruslan Abdulgani Mhd Roem Hairi Hadi, Laksamana Poegoeh, Agus Sudono Harry Tjan Hardi SH Letjen Djatikusumo Maj.Gen Sutjipto KH Musto'in Ramly Maj Gen Muskita Maj Gen Alamsyah Let Gen Sarbini TD Hafas Sajuti Melik Haji Princen Hugeng Imam Santoso Hairi Hadi, Laksamana Poegoeh Subchan Liem Bian Kie Suripto Mhd Roem Maj.Gen Wijono Yassien Ron Hatley 30 General Nasution (24-7-73) Nasution (N) first suggested a return to the 1945 constitution in 1955 during the Pemilu. When Subandrio went to China in 1965, Nasution suggested that if China really wanted to help Indonesia, she should cut off supplies to Hongkong. According to Nasution, BK was serious about Maphilindo but Aidit convinced him that he was a world leader, not just a regional leader. In 1960 BK became head of Peperti which made him very influential in the AD with authority over the regional commanders. In 1962 N was replaced by Yani. According to the original concept, N would become Menteri Hankam/Panglima ABRI. However Omar Dhani wrote a letter to BK (probably proposed by Subandrio or BK himself). Sukarno (chief of police) supported Omar Dhani secara besar). Only Martadinata defended to original plan while Yani was 'plin-plan'. Meanwhile Nasution had proposed Gatot Subroto as the new Kasad but BK rejected this because he felt that he could not menguasai Gatot. Nas then proposed the two Let.Gens. - Djatikusuma and Hidayat but they were rejected by BK. -

INDO 33 0 1107016894 89 121.Pdf (1.388Mb)

PATTERNS OF MILITARY CONTROL IN THE INDONESIAN HIGHER CENTRAL BUREAUCRACY John A. MacDougall* Summary This article analyzes current military penetration of Indonesia's higher central government bureaucracy. Any civilian or military officeholder in this bureaucracy is referred to as a karyawan. The article focuses on the incumbent Cabinet and topmost echelon of civil service officials. Findings are based on public biographies of these persons and published specialized secondary sources on the Indonesian military. The principal conclusions follow below. The Higher Central Bureaucracy The Indonesian military has long played a "dual civil and military function." Military karyawan, active duty and retired officers in civilian assignments, comprise an increasingly visible, influential, and strategic segment of the dominant military faction, that of President Suharto and his 1945 Generation supporters. --The military karyawan in the higher central bureaucracy are especially critical actors in maintaining the Suharto regime. --Together with their civilian karyawan colleagues, virtually all of them wield decision-making powers of some considerable degree. --Some mix of military and civilian karyawan occurs in all Cabinet Departments except the Department of Defense and Security, now entirely military-controlled. --The Indonesian armed forces' doctrinal commitment to preventing civilian con trol of the military has resulted in the Department of Defense and Security be coming effectively equivalent to the consolidated armed forces' staff and command structure. Extent of Military Penetration Active and retired military karyawan now occupy half the positions in the Indo nesian higher central bureaucracy. --At the highest levels, military penetration remains near complete (the President and his principal immediate aides) or has increased (Coordinating Ministers) over the course of the New Order regime (1966 to the present). -

The Existence of the State Minister in the Government System After the Amendment to the 1945 Constitution

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 5, Series. 1 (May. 2020) 51-78 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Existence of the State Minister in the Government System after the Amendment to the 1945 Constitution ParbuntianSinaga Doctor of Law, UniversitasKrisnadwipayana Jakarta Po Box 7774 Jat Cm Jakarta 13077, Indonesia Abstract: Constitutionally, the existence of ministers called cabinet or council of ministers in a presidential government system is an inseparable part of the executive power held by the President. The 1945 Constitution after the amendment, that the presence of state ministers as constitutional organs is part of the power of the President in running the government. This study aims to provide ideas about separate arrangements between state ministries placed separately in Chapter V Article 17 to Chapter III of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia concerning the authority of the state government or the power of the President, and also regarding the formation, amendment and dissolution of the ministries regulated in legislation. This study uses a normative juridical research approach. The results of the study show that the Minister of State is the President's assistant who is appointed and dismissed to be in charge of certain affairs in the government, which actually runs the government, and is responsible to the President. The governmental affairs referred to are regulated in Law No. 39 of 2008 concerning the State Ministry, consisting of: government affairs whose nomenclature is mentioned in the 1945 NRI Constitution, government affairs whose scope is mentioned in the 1945 NRI Constitution, and government affairs in the context of sharpening, coordinating, and synchronizing government programs. -

THE NEW ORDER and the ECONOMY J. Panglaykim and K. D

THE NEW ORDER AND THE ECONOMY J. Panglaykim and K. D. Thomas It is rather ironic to recall President Sukarno’s "banting stir" speech of April 11, 1965. Just one year and a day after that speech, the Sultan of Jogjakarta, Presidium member for economic and financial affairs outlined the economic policy of the "perfected" Dwikora cabinet, which was formed as a result of the first major cabinet reshuffle after the abortive coup. In it, the Sultan envisaged a substantial "turn of the wheel", but it was a "banting stir" in a direction not intended by the President the previous year when he had concentrated his attacks on foreign capital and private entrepreneurs. In the months that followed the Sultan’s speech, there was a vigorous debate among the nation’s intellectuals on the content of In donesian socialism in the new era and the way in which the "just and prosperous society" so dear to the President1 was to be attained. Prominent in the debates were several groups of intellec tuals scattered throughout the capital city: some affiliated to political parties, others in such organizations as the In tellectuals’ Action Group (KASI). Membership in the various groups is not mutually exclusive. It is possible for a per son to belong to a political party and also to be an active participant in several formal and informal groups interested in discussing economic problems and taking steps to influence the government. So a program issued under the name of a par ticular organization cannot be regarded as the brain-child of that group alone. -

H. Bachtiar Bureaucracy and Nation Formation in Indonesia In

H. Bachtiar Bureaucracy and nation formation in Indonesia In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 128 (1972), no: 4, Leiden, 430-446 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 09:13:37AM via free access BUREAUCRACY AND NATION FORMATION IN INDONESIA* ^^^tudents of society engaged in the study of the 'new states' in V J Asia and Africa have often observed, not infrequently with a note of dismay, tihe seeming omnipresence of the government bureau- cracy in these newly independent states. In Indonesia, for example, the range of activities of government functionaries, the pegawai negeri in local parlance, seems to be un- limited. There are, first of all and certainly most obvious, the large number of people occupying official positions in the various ministries located in the captital city of Djakarta, ranging in each ministry from the authoritative Secretary General to the nearly powerless floor sweepers. There are the territorial administrative authorities, all under the Minister of Interna! Affairs, from provincial Governors down to the village chiefs who are electecl by their fellow villagers but who after their election receive their official appointments from the Govern- ment through their superiors in the administrative hierarchy. These territorial administrative authorities constitute the civil service who are frequently idenitified as memibers of the government bureaucracy par excellence. There are, furthermore, as in many another country, the members of the judiciary, personnel of the medical service, diplomats and consular officials of the foreign service, taxation officials, technicians engaged in the construction and maintenance of public works, employees of state enterprises, research •scientists, and a great number of instruc- tors, ranging from teachers of Kindergarten schools to university professors at the innumerable institutions of education operated by the Government in the service of the youthful sectors of the population. -

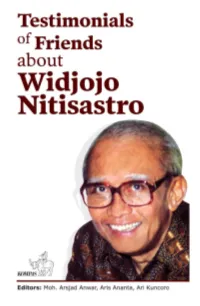

Prof. Dr. Widjojo Nitisastro

Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, Januari 2008 Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Publishing by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, Januari 2008 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70008004 Translated: Harry Bhaskara Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editors: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. Rahmawanta Cover foto by: family document All rights reserved. -

Biography Kh. Idham Chalid: Study the Value of Nationalism As a Learning

The Kalimantan Social Studies Journal Vol. 1, (1), Oct 2019 BIOGRAPHY KH. IDHAM CHALID: STUDY THE VALUE OF NATIONALISM AS A LEARNING RESOURCE ON SOCIAL STUDIES Bambang Subiyakto [email protected] Social Studies Department, FKIP Lambung Mangkurat University Mutiani [email protected] Social Studies Department, FKIP Lambung Mangkurat University Reni Ridati [email protected] Social Studies Department, FKIP Lambung Mangkurat University Abstract Integrasi nilai nasionalisme dari Idham Chalid sebagai sumber belajar IPS dimaksudkan agar khalayak mendapat pengetahuan dan pemahaman pentingnya nilai nasionalisme dan menghargai perjuangan pahlawan nasional dari Kalimantan Selatan. Pendekatan kualitatif dan metode biografi digunakan pada penelitian ini. Teknik pengumpulan data dilakukan melalui tiga tahapan, yaitu: observasi, wawancara, dan dokumentasi. Analisis data dipakai dengan model Miles dan Huberman yakni: reduksi data, penyajian data, dan verifikasi. Adapun uji keabsahan data yang dilakukan adalah triangulasi teknik. Hasil penelitian dipaparkan menjadi dua bagian, yaitu: 1) biografi Idham Chalid dari mulai pada masa kecil sampai wafat, dan 2) nilai nasionalisme yang muncul dari biografi Idham Chalidberupa kerelaan berkorban, bangga sebagai bangsa Indonesia, dan sifat berani. Keseluruhan nilai ini relevan dijadikan sumber belajar IPS. Relevansi nilai nasionalisme sebagai sumber belajar IPS didasari oleh analisis muatan materi pelajaran IPS pada kelas VIII. Dengan demikian, penelitian berkontribusi bagi guru dan peserta didik karena dapat mengintegrasikan nilai nasionalisme pada pembelajaran IPS sebagai sumber belajar. Keywords: Biography, Value Nationalism and Learning Resources on Social Studies. PRELIMINARY Talking about nationalism in the life of the nation in the era of globalization always has appeal. Starting with many opinions regarding nationalism the younger generation began to fade. -

Rhere Were Also Rumours in Early 1967 (Eg in El Bahar) About the Brawidjaya

Liem Bian Kee (Jusuf Wanandi) 11 February 1971 At first no one in Kap-Gestapu thought of opposing BK, including Subchan. It was only in February when BK criticised the demonstators along with Chaeral and Subandrio at a Front Nasional meeting that they became anti-BK. Chaerul Saleh was strongly anti-PK!. But he was not strongly with the Kap-Gestapu. In November Ali Murtopo went to him for money for the big Kap-Gestapu rally. He asked Chaerul whether he was pro or anti-Suharto. Eventually Chaerul gave the money. Earlier he had refused LBK when LBK asked. Various Partindo people such as Amunanto (and one other who was more important?) were behind the ideal of the Front Nasional Gaya Baru, which was to be organised like the army with Seksi/lntell, Seksi II? Etc. It was to be the Barisan Soekarno setjara fisik. Ultimately the political parties would e greatly weakened in such a Front. This was put forward by Chaerul in the rally in Feb 66. Ruslan was a rival of Subandrio. Unlike Chaerul, Ruslan cultivated good relations with Yani. After the coup, Ruslan was often used by Suharto to make approaches quietly to Sukarno, especially in the field of foreign policy. When Nasution was dismissed from Cabinet in Feb 66, Suharto told him to refuse; however Nasution was not prepared to force a showdown. Thus Suharto was forced to go slowly. The SUAD decided on a plan to metjulik and maybe kill Subandrio, Jusuf Muda Dalam and some other ministers. Suharto was present at the meeting. -

Explaining Indonesia's Relations with Singapore During the New Order Period:The Case of Regime Maintenance and Foreign Policy

No. 10 Explaining Indonesia’s Relations with Singapore During the New Order Period: The Case of Regime Maintenance and Foreign Policy Terence Lee Chek Liang Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Singapore MAY 2001 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies. IDSS Working Paper Series 1. Vietnam-China Relations Since The End of The Cold War (1998) Ang Cheng Guan 2. Multilateral Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific Region: (1999) Prospects and Possibilities Desmond Ball 3. Reordering Asia: “Cooperative Security” or Concert of Powers? (1999) Amitav Acharya 4. The South China Sea Dispute Re-visited (1999) Ang Cheng Guan 5. Continuity and Change In Malaysian Politics: Assessing the Buildup (1999) to the 1999-2000 General Elections Joseph Liow Chin Yong 6. ‘Humanitarian Intervention in Kosovo’ as Justified, Executed and (2000) Mediated by NATO: Strategic Lessons for Singapore Kumar Ramakrishna 7. Taiwan’s Future: Mongolia or Tibet? (2001) Chien-peng (C.P.) Chung 8. Asia-Pacific Diplomacies: Reading Discontinuity in Late-Modern (2001) Diplomatic Practice Tan See Seng 9. Framing “South Asia”: Whose Imagined Region? (2001) Sinderpal Singh 10. Explaining Indonesia’s Relations with Singapore During the New (2001) Order Period : The Case of Regime Maintenance and Foreign Policy Terence Lee Chek Liang The Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies was established in 1996 to: • Conduct research on security and strategic issues pertinent to Singapore and the region. • Provide general and post-graduate training in strategic studies, defence management, and defence technology. -

Table of Contents

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Elites and economic policies in Indonesia and Nigeria, 1966-1998 Fuady, A.H. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Fuady, A. H. (2012). Elites and economic policies in Indonesia and Nigeria, 1966-1998. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Elites and Policies Economicin Indonesiaand Nigeria, 1966 Elites and Economic Policies in Indonesia and Nigeria, 1966-1998 Ahmad Helmy Fuady - 1998 A . H . Fuady 2012 Elites and Economic Policies in Indonesia and Nigeria, 1966-1998 Ahmad Helmy Fuady Copyright © 2012 Ahmad Helmy Fuady. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronics, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the proprietor. -

Archipelagic Networks of Power: Village Electrification, Politics, Ideology, and Dual National Identity in Indonesia (1966-1998)

ARCHIPELAGIC NETWORKS OF POWER: VILLAGE ELECTRIFICATION, POLITICS, IDEOLOGY, AND DUAL NATIONAL IDENTITY IN INDONESIA (1966-1998) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Yulianto Salahuddin Mohsin January 2015 © 2015 Yulianto Salahuddin Mohsin ARCHIPELAGIC NETWORKS OF POWER: VILLAGE ELECTRIFICATION, POLITICS, IDEOLOGY, AND DUAL NATIONAL IDENTITY IN INDONESIA (1966-1998) Yulianto Salahuddin Mohsin, Ph.D. Cornell University 2015 This dissertation examines Indonesia’s Village Electrification Program in the so-called “New Order” period (1966-1998) under Soeharto. I investigate the New Order government’s motives to supply electricity to the countryside, the ways it built the electrical infrastructure to light the villages, and the meanings attributed to electricity by some of the country’s leaders, bureaucrats, the Indonesian State Electricity Company (PLN) engineers, and villagers. I argue that the Soeharto government’s rural electrification project was entangled with narratives of Indonesia’s dual national identity. Domestically, Soeharto’s program to light rural areas was governed by an overwhelming desire to establish an internal national identity as a “developing Pancasila nation,” i.e. as a developmental nation- state based on the state ideology Pancasila. The principles heavily influenced the program and resulted in a “grid without a grid,” i.e. a network of mostly diesel power generating stations that were not all connected physically. Instead PLN linked these power plants organizationally by operating and maintaining them. In addition, nationally the New Order government also connected the provision of electricity in the villages with electoral politics.