Prof. Dr. Widjojo Nitisastro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Thee Kian Wie's Major

Economics and Finance in Indonesia Vol. 61 No. 1, 2015 : 41-52 p-ISSN 0126-155X; e-ISSN 2442-9260 41 The Indonesian Economy from the Colonial Extraction Period until the Post-New Order Period: A Review of Thee Kian Wie’s Major Works Maria Monica Wihardjaa,∗, Siwage Dharma Negarab,∗∗ aWorld Bank Office Jakarta bIndonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) Abstract This paper reviews some major works of Thee Kian Wie, one of Indonesia’s most distinguished economic historians, that spans from the Colonial period until the post-New Order period. His works emphasize that economic history can guide future economic policy. Current problems in Indonesia were resulted from past policy failures. Indonesia needs to consistently embark on open economic policies, free itself from "colonial period mentality". Investment should be made in rebuilding crumbling infrastructure, improving the quality of health and education services, and addressing poor law enforcement. If current corruption persists, Indone- sia could not hope to become a dynamic and prosperous country. Keywords: Economic History; Colonial Period; Industrialization; Thee Kian Wie Abstrak Tulisan ini menelaah beberapakarya besar Thee Kian Wie, salah satu sejarawan ekonomi paling terhormat di Indonesia, mulai dari periode penjajahan hingga periode pasca-Orde Baru. Karya Beliau menekankan bahwa sejarah ekonomi dapat memberikan arahan dalam perumusan kebijakan ekonomi mendatang. Permasalahan yang dihadapi Indonesia dewasa ini merupakan akibat kegagalan kebijakan masa lalu. In- donesia perlu secara konsisten menerapkan kebijakan ekonomi terbuka, membebaskan diri dari "mentalitas periode penjajahan". Investasi perlu ditingkatkan untuk pembangunan kembali infrastruktur, peningkatan kualitas layanan kesehatan dan pendidikan, serta pembenahan penegakan hukum. Jika korupsi saat ini berlanjut, Indonesia tidak dapat berharap untuk menjadi negara yang dinamis dan sejahtera. -

Title First Name Last (Family) Name Officecountry Jobtitle Organization 1 Mr. Sultan Abou Ali Egypt Professor of Economics

Last (Family) # Title First Name OfficeCountry JobTitle Organization Name 1 Mr. Sultan Abou Ali Egypt Professor of Economics Zagazig University 2 H.E. Maria del Carmen Aceña Guatemala Minister of Education Ministry of Education 3 Mr. Lourdes Adriano Philippines Poverty Reduction Specialist Asian Development Bank (ADB) 4 Mr. Veaceslav Afanasiev Moldova Deputy Minister of Economy Ministry of Economy Faculty of Economics, University of 5 Mr. Saleh Afiff Indonesia Professor Emeritus Indonesia 6 Mr. Tanwir Ali Agha United States Executive Director for Pakistan The World Bank Social Development Secretariat - 7 Mr. Marco A. Aguirre Mexico Information Director SEDESOL Palli Karma Shahayak Foundation 8 Dr. Salehuddin Ahmed Bangladesh Managing Director (PKSF) Member, General Economics Ministry of Planning, Planning 9 Dr. Quazi Mesbahuddin Ahmed Bangladesh Division Commission Asia and Pacific Population Studies 10 Dr. Shirin Ahmed-Nia Iran Head of the Women’s Studies Unit Centre Youth Intern Involved in the 11 Ms. Susan Akoth Kenya PCOYEK program Africa Alliance of YMCA Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 12 Ms. Afrah Al-Ahmadi Yemen Head of Social Protection Unit Social Development Fund Ministry of Policy Development and 13 Ms. Patricia Juliet Alailima Sri Lanka Former Director General Implementation Minister of Labor and Social Affairs and Managing Director of the Socail 14 H.E. Abdulkarim I. Al-Arhabi Yemen Fund for Development Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs 15 Dr. Hamad Al-Bazai Saudi Arabia Deputy Minister Ministry of Finance 16 Mr. Mohammad A. Aldukair Saudi Arabia Advisor Saudi Fund for Development 17 Ms. Rashida Ali Al-Hamdani Yemen Chairperson Women National Committee Head of Programming and Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 18 Ms. -

July 2009 Bi -Weekly Bulletin Issue 13 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun

Political Issues Environment Issues Economic Issues Regional/International Issues RELATED EVENTS TO INDONESIA: Socio-Cultural Issues Useful links of Indonesia: Government July 2009 Bi -Weekly Bulletin www.indonesia.go.id Issue 13 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Indonesia News & Views 1 2 3 4 5 July 1, 2009 Department of Foreign Affairs www.indonesian-embassy.fi www.deplu.go.id 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Top quotes inside this issue: Ministry of Cultural and Tourism ♦ "The upcoming presidential 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 election must be able to www.budpar.go.id , produce a national leadership www.my-indonesia.info that can improve the people's 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 welfare based on the principles of justice and civil National Agency for Export rights ." (page 1) Development 27 28 29 30 31 ♦ ”Border issues cannot be www.nafed.go.id settled through negotiations in a short time. It's not something we start one day and the next Investment Coordinating Board >>> July 17-19, 2009 South Sumatra day we are finished. It's not www.bkpm.go.id Kerinci Cultural Festival, Jambi only we and Malaysia, but Further information, please visit One of the greatest kingdoms in Indonesian history, the Buddhist Empire of many other countries www.pempropjambi.go.id Sriwijaya, prospered along the banks of Musi River in South Sumatra over a experienced this.” (page 3) thousand years ago. ♦ ”Indonesia is experiencing a Located on the southern-most rim of the South China Sea, close to the one of positive trend as indicated by the world’s busiest shipping lanes linking the Far East with Europe, the the improvement in the com- Location: Raja Ampat, Papua, Indonesia Region’s historical background is rich and colourful. -

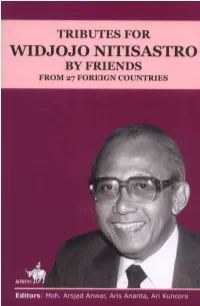

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

00 Seasians ASEM.Indd 10 9/18/14 10:52:23 AM

00 SEAsians_ASEM.indd 10 9/18/14 10:52:23 AM ecollections Reproduced from Recollections: The Indonesian Economy, 1950s-1990s, edited by Thee Kian Wie (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2003). This version was obtained electronically direct from the publisher on condition that copyright is not infringed. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior permission of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Individual articles are available at < http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg > The Indonesia Project is a major international centre of research and graduate training on the economy of Indonesia. Established in 1965 in the Division of Economics of the Australian National University’s Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, the Project is well known and respected in Indonesia and in other places where Indonesia attracts serious scholarly and official interest. Funded by ANU and the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), it monitors and analyses recent economic developments in Indonesia; informs Australian governments, business, and the wider community about those developments, and about future prospects; stimulates research on the Indonesian economy; and publishes the respected Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) in Singapore was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia, particularly the many-faceted problems of stability and security, economic development, and political and social change. ISEAS is a major publisher and has issued over 1,000 books and journals on Southeast Asia. The Institute’s research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). -

Negotiating Polygamy in Indonesia

Negotiating Polygamy in Indonesia. Between Muslim Discourse and Women’s Lived Experiences Nina Nurmila Dra (Bandung, Indonesia), Grad.Dip.Arts (Murdoch University, Western Australia), MA (Murdoch University) Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2007 Gender Studies - Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Unlike most of the literature on polygamy, which mainly uses theological and normative approaches, this thesis is a work of social research which explores both Indonesian Muslim discourses on polygamy and women’s lived experiences in polygamous marriages in the post-Soeharto period (after 1998). The thesis discusses the interpretations of the Qur’anic verses which became the root of Muslim controversies over polygamy. Indonesian Muslim interpretations of polygamy can be divided into three groups based on Saeed’s categorisation of the Muslim approaches to the Qur’an (2006b: 3). First, the group he refers to as the ‘Textualists’ believe that polygamy is permitted in Islam, and regard it as a male right. Second, the group he refers to as ‘Semi-textualists’ believe that Islam discourages polygamy and prefers monogamy; therefore, polygamy can only be permitted under certain circumstances such as when a wife is barren, sick and unable to fulfil her duties, including ‘serving’ her husband’s needs. Third, the group he calls ‘Contextualists’ believe that Islam implicitly prohibits polygamy because just treatment of more than one woman, the main requirement for polygamy, is impossible to achieve. This thesis argues that since the early twentieth century it was widely admitted that polygamy had caused social problems involving neglect of wives and their children. -

Indonesia Assessment 1991

Indonesia Assessment 1991 Hal Hill, editor Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Indonesia Assessment 1991 Proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Indonesia Project, Department of Economics and Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU Hal Hill (ed.) Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University Canberra, 1991 © Hal Hill and the several authors each in respect of the papers contributed by them; for the full list of the names of such copyright owners and the papers in respect of which they are the copyright owners see the Table of Contents of this volume. This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealings for the purpose of study, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries may be made to the publisher. First published 1991, Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University. Printed and manufactured in Australia by Panther Publishing and Press. Distributed by Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University GPO Box 4 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia (FAX: 06-257-1 893) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry Indonesia Update Conference (1991 Australian National University). Indonesia Assessment, proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Bibliography. Includes index ISBN 0 7315 1291 X 1. Education, Higher - Indonesia - Congresses. 2. Indonesia - Economic conditions - 1966- - Congresses. 3. Indonesia - Politics and government- 1%6- - Congresses. I. -

Sector Ienvironmental Impact Assessment

The Study on Comprehensive Water Management of Main Report Musi River Basin in the Republic of Indonesia Final Report CHAPTER 3 PRESENT CONDITION OF THE BASIN AND BASIC ANALYSIS 3.1 General Natural Conditions The general natural condition described in this section mainly refers to the Musi River Basin Study in 1989, updating the information and data. 3.1.1 Topography The Musi River Basin covers a total of 59,942 km2 in the south of Sumatra Island between 2°17’ and 4°58’ South latitude and between 102°4’ and 105°20’ East Longitude. It covers most of South Sumatra Province, and only small parts of the Bengkulu, Jambi and Lampung provinces as shown in the Location Map. The topography of the Musi River Basin can be broadly divided into five zones; namely, from the west, the Mountain Zone, the Piedmont Zone, the Central Plains, the Inland Swamps and the Coastal Plains. The Mountain Zone comprises the northwestern to southwestern part of the study area and is composed of valleys, highland plateaus and volcanic cones. The Piedmont Zone is an approximately 40 km wide transition belt between the Mountain Zone and the Central Plains. It is an undulating to hilly area with some flat plains. The central plains consist of three sections, uplands, flood plains and river levees. The Inland Swamps comprise the natural river levees and back swamps. The back swamps are less elevated than the river level and flooded during the rainy season. The Coastal Plain comprises the lowlands along the coast and the deltaic northeastern lowlands, naturally covered with peat swamp forest. -

The Indonesia Atlas

The Indonesia Atlas Year 5 Kestrels 2 The Authors • Ananias Asona: North and South Sumatra • Olivia Gjerding: Central Java and East Nusa Tenggara • Isabelle Widjaja: Papua and North Sulawesi • Vera Van Hekken: Bali and South Sulawesi • Lieve Hamers: Bahasa Indonesia and Maluku • Seunggyu Lee: Jakarta and Kalimantan • Lorien Starkey Liem: Indonesian Food and West Java • Ysbrand Duursma: West Nusa Tenggara and East Java Front Cover picture by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA. All other images by students of year 5 Kestrels. 3 4 Welcome to Indonesia….. Indonesia is a diverse country in Southeast Asia made up of over 270 million people spread across over 17,000 islands. It is a country of lush, wild rainforests, thriving reefs, blazing sunlight and explosive volcanoes! With this diversity and energy, Indonesia has a distinct culture and history that should be known across the world. In this book, the year 5 kestrel class at Nord Anglia School Jakarta will guide you through this country with well- researched, informative writing about the different pieces that make up the nation of Indonesia. These will also be accompanied by vivid illustrations highlighting geographical and cultural features of each place to leave you itching to see more of this amazing country! 5 6 Jakarta Jakarta is not that you are thinking of.Jakarta is most beautiful and amazing city of Indonesia. Indonesian used Bahasa Indonesia because it is easy to use for them, it is useful to Indonesian people because they used it for a long time, became useful to people in Jakarta. they eat their original foods like Nasigoreng, Nasipadang. -

Democracy in Indonesia

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1994-06 Democracy in Indonesia Kusmayati, Anne Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/28094 DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY CA 93943-5101 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Democracy In Indonesia by Anne JKusmayati Civilian Staff, Indonesian Department of Defense Engineering in Community Nutrition and Family Resources, Bogor Agricultural University, 1983. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN INTERNATIONAL RESOURCE PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT from the NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL June, 1994 David R. Wfiipple, Jr.,j£hairman REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204. Arlington. VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 1994. Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA 6. AUTHOR(S): Anne Kusmayati 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION Monterey CA 93943-5000 REPORT NUMBER SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Fifty Years of Indonesian Development: "One Nation," Under Capitalism

Fifty Years of Indonesian Development: "One Nation," Under Capitalism ... by Brian McCormack Department of Political Science Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona 85287-2001 USA e-mail: [email protected] Cite: McCormack, Brian. (1999). "Fifty Years oflndoncsian Development: 'One Nation,' Under Capitalism ... " Journal of World-Systems Research http://jwsr.ucr.edu/ 5: 48-73. (cJ 1999 Brian McCormack. [Page 48] Journal o.lWorld-Systems Research In Indonesia much uncertainty remains in the wake of the dramatic changes that unfolded in the latter half of the l990's. By the end of the 20th century, the Indonesian economy was in ruins. The concept of democracy remained contested. The transportation and communication system that once at lea'lt minimall y linked the diverse and at times disparate area'l and peoples of the Indonesian archipelago into an Andcrsonian imagined national community collapsed, making more likely movcmcnt'l for regional autonomy, in turn, making the status of an Indonesian nation itself uncertain. One thing that is certain, however, is that Socharto, the "Father of Development," is history. As political and economic policy makers in Indonesia, the United States, and around the world, and more importantly, Indonesia's men, women, and children pick up the pieces, it is our responsibility to look back and consider the past fifty years. Indonesian development ha'l been marked by a struggle between two opposing forces: one that is commensurate with self-reliance predicated upon an ideology of nationalism, and another that positions Indonesia within global capitalism. The issue that I shall address here is the degree to which the strategies of development were determined by a culture of capitalism or, alternatively, by a culture of nationalism. -

Indonesian Authors in Geneeskundige Tijdschrift Voor Nederlands Indie As Constructors of Medical Science

Volume 16 Number 2 ISSN 2314-1234 (Print) Page October 2020 ISSN 2620-5882 (Online) 123—142 Indonesian Authors in Geneeskundige Tijdschrift voor Nederlands Indie as Constructors of Medical Science WAHYU SURI YANI Alumny History Department, Universitas Gadjah Mada Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract Access to the publication Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië (GTNI), Keywords: a Dutch Indies medical journal, was limited to European doctors. Although Stovia Bahder Djohan; (School ter Opleiding van Inlandsche Artsen) was established to produce indigenous Constructor; (Bumiputra) doctors, its students and graduates were not given access to GTNI. In GTNI; response, educators at Stovia founded the Tijdschrift Voor Inlandsche Geneeskundigen Leimena; (TVIG) as a special journal for indigenous doctors. Due to limited funds, TVIG – Stovia; Pribumi the only scientific medical publication for indigenous doctors – ceased publication Doctors; TVIG in 1922. The physicians formed Vereeniging van Inlandsche Geneeskundigen (VIG) an association for pribumi (native) doctors to express various demands for equal rights, one of which was the right to access GTNI. The protests and demands of the bumiputra doctors resulted not only in being granted reading access rights but also being able to become writers for GTNI. Bumiputra doctors who contributed to GTNI included Bahder Djohan and Johannes Leimena. However, they were not the only authors who contributed to GTNI during the Dutch East Indies era. After Indonesia became independent, both doctors played major roles in laying the foundation for Indonesia’s health education system and implementing village-based health policies. This article is part of a research project on Indonesia’s health history using the archives of the GTNI, TVIG and books written by doctors who contributed to GTNI which were published from the early twentieth century onwards.