Downloaded from the Innovations for Successful Societies Website, Users Must Read and Accept the Terms on Which We Make These Items Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nabbs-Keller 2014 02Thesis.Pdf

The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Author Nabbs-Keller, Greta Published 2014 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2823 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366662 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By GRETA NABBS-KELLER October 2013 The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Greta Nabbs-Keller B.A., Dip.Ed., M.A. School of Government and International Relations Griffith Business School Griffith University This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 2013 Abstract How democratisation affects a state's foreign policy is a relatively neglected problem in International Relations. In Indonesia's case, there is a limited, but growing, body of literature examining the country's foreign policy in the post- authoritarian context. Yet this scholarship has tended to focus on the role of Indonesia's legislature and civil society organisations as newly-empowered foreign policy actors. Scholars of Southeast Asian politics, meanwhile, have concentrated on the effects of Indonesia's democratisation on regional integration and, in particular, on ASEAN cohesion and its traditional sovereignty-based norms. For the most part, the literature has completely ignored the effects of democratisation on Indonesia's foreign ministry – the principal institutional actor responsible for foreign policy formulation and conduct of Indonesia's diplomacy. Moreover, the effect of Indonesia's democratic transition on key bilateral relationships has received sparse treatment in the literature. -

Indonesian Technocracy in Transition: a Preliminary Analysis*

Indonesian Technocracy in Transition: A Preliminary Analysis* Shiraishi Takashi** Indonesia underwent enormous political and institutional changes in the wake of the 1997–98 economic crisis and the collapse of Soeharto’s authoritarian regime. Yet something curious happened under President Yudhoyono: a politics of economic growth has returned in post-crisis decentralized, democratic Indonesia. The politics of economic growth is politics that transforms political issues of redistribution into problems of output and attempts to neutralize social conflict in favor of a consensus on growth. Under Soeharto, this politics provided ideological legitimation to his authoritarian regime. The new politics of economic growth in post-Soeharto Indo- nesia works differently. Decentralized democracy created a new set of conditions for doing politics: social divisions along ethnic and religious lines are no longer suppressed but are contained locally. A new institutional framework was also cre- ated for the economic policy-making. The 1999 Central Bank Law guarantees the independence of the Bank Indonesia (BI) from the government. The Law on State Finance requires the government to keep the annual budget deficit below 3% of the GDP while also expanding the powers of the Ministry of Finance (MOF) at the expense of National Development Planning Agency. No longer insulated in a state of political demobilization as under Soeharto, Indonesian technocracy depends for its performance on who runs these institutions and the complex political processes that inform their decisions and operations. Keywords: Indonesia, technocrats, technocracy, decentralization, democratization, central bank, Ministry of Finance, National Development Planning Agency At a time when Indonesia is seen as a success story, with its economy growing at 5.9% on average in the post-global financial crisis years of 2009 to 2012 and performing better * I would like to thank Caroline Sy Hau for her insightful comments and suggestions for this article. -

Pacnet Number 48 July 7, 2009

Pacific Forum CSIS Honolulu, Hawaii PacNet Number 48 July 7, 2009 campaign, pollsters still believe that SBY could still win with The Indonesian Presidential Election: SBY Cruising to a 60 percent of the vote. Second Term? By Alphonse F. La Porta The issues favor SBY and his running mate. The top three Alphonse F. La Porta ([email protected]) is a retired qualities sought by the voters, according to LSI, are integrity, U.S. Foreign Service Officer, who has served as ambassador empathy, and competence. SBY has staked his campaign on a to Mongolia, president of the U.S.-Indonesia Society, and in strong anti-corruption platform, and he has bolstered the Indonesia and other Southeast Asian posts. He recently government’s performance during his first term and returned from a visit to Jakarta. deliberately chose “Mr. Clean” – Boediono – as his running Not surprisingly, the Indonesian presidential election to be mate to underscore his determination to pursue wrongdoers held on July 8 looks differently in Jakarta than from abroad. (including his son’s father-in-law, who was sent to jail last Foreign observers, bolstered by optimistic polling data, see week on a graft charge). In comparison, all the opposition President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, or SBY as he is candidates are vulnerable on integrity issues. familiarly known, cruising to a first-round victory with a Campaigning and the Media majority close to the 61 percent he garnered in 2004. Backing by media moguls and businessmen, including The view from Jakarta, however, is much more Surya Paloh, the owner of Indonesia’s largest private complicated. -

Democratization and Decentralization in Post-Soeharto Indonesia: Understanding Transition Dynamics Author(S): Paul J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of the South Pacific Electronic Research Repository Democratization and Decentralization in Post-Soeharto Indonesia: Understanding Transition Dynamics Author(s): Paul J. Carnegie Source: Pacific Affairs, Vol. 81, No. 4 (Winter, 2008/2009), pp. 515-525 Published by: Pacific Affairs, University of British Columbia Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40377625 Accessed: 11-08-2016 02:45 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40377625?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Pacific Affairs, University of British Columbia is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Pacific Affairs This content downloaded from 144.120.77.73 on Thu, 11 Aug 2016 02:45:50 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PERSPECTIVES Democratization and Decentralization in Post-Soeharto Indonesia: Understanding Transition Dynamics Paul J. Carnegie 1998, following Soeharto's demise, Indonesia underwent a transition from authoritarian rule amidst much anticipation but no small amount of concern.1 Thankfully, in the intervening years, it has now become the world's third largest democracy.2 Yet, how and why the archipelago's democratic institutions became established and accepted remain difficult questions to answer. -

Voters and the New Indonesian Democracy

VOTERS AND THE NEW INDONESIAN DEMOCRACY Saiful Mujani Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI) R. William Liddle The Ohio State University November 2009 RESEARCH QUESTIONS • WHY HAVE INDONESIAN VOTERS VOTED AS THEY HAVE IN THREE PARLIAMENTARY AND TWO DIRECT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS IN 1999, 2004, AND 2009? • WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THESE PATTERNS OF VOTING BEHAVIOR FOR THE QUALITY OF INDONESIAN DEMOCRACY? THE EMPIRICAL RESEARCH SIX NATIONAL LSI OPINION SURVEYS: ONE IN 1999, THREE IN 2004, TWO IN 2009. FACTORS EXAMINED: SOCIOLOGICAL (RELIGION/ALIRAN, REGION/ETHNICITY, SOCIAL CLASS) LEADERS/CANDIDATES PARTY ID MEDIA CAMPAIGN (2009) INCUMBENT’S PERFORMANCE Parties in post-transition democratic Indonesian parliamentary elections: percent of votes (and seats) PARTIES 1999 2004 2009 votes (seats) votes (seats) votes (seats) PDIP 34 (33) 18.5 (20) 14 (17) GOLKAR 22 (26) 22 (23) 14 (19) PKB 13 (11) 11 (10) 5 (5) PPP 11 (13) 8 (11) 5 (7) PAN 7 (7) 6 (10) 6 (8) PK/PKS 2 7 (8) 8 (10) DEMOKRAT - 7 (10) 21 (26) GERINDRA - - 5 (5) HANURA - - 4 (3) OTHER 14 (8) 20 (9) 28 (-) TOTAL 100.0 100.0 100.0 Vote for presidents/vice-presidents in democratic Indonesian elections 2004-2009 (%) President-Vice President Pairs 2004 2004 2009 First Round Second Round Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono- 34 61 61 Jusuf Kalla (2004); Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono- Boediono (2009) Megawati Sukarnoputri- 26 39 27 Hasyim Muzadi (2004); Megawati Sukarnoputri- Prabowo Subianto (2009) Wiranto-Solahuddin Wahid 24 12 (2004); Jusuf Kalla-Wiranto (2009) Amien Rais-Siswono 14 Yudhohusodo Hamzah Haz-Agum -

Backlash Against Foreign Investment Regime: Indonesia’S Experience

Backlash against Foreign Investment Regime: Indonesia’s Experience Herliana A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Dongsheng Zang, Chair John O. Haley Melissa Durkee Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Law ©Copyright 2017 Herliana ii University of Washington Abstract Backlash against Foreign Investment Regime: Indonesia’s Experience Herliana Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Dongsheng Zang School of Law This study investigates Indonesia’s changing attitude from embracing to repudiating foreign direct investments. Opened its door for foreign investment in the late of 1960s and enjoyed significant economic growth as the result, the country suddenly changed its foreign investment policy in 2012 to be more protectionist towards domestic investors and skeptical towards foreign investors. The essential issues to be discussed in this research are: what motivates Indonesia to move away from global investment regime; what actions the country has taken as manifestation of resentment against the regime; and who are the actors behind such a backlash. This is a qualitative study which aims at gaining a deep understanding of a legal development of Indonesia’s foreign investment. It aims to provide explanation of the current phenomenon taking place in the country. Data were collected through interviews and documents. This research reveals that liberalization of foreign investment law has become the major cause of resentment towards the foreign investment. Liberalization which requires privatization and openness toward foreign capital has failed to deliver welfare to the Indonesian people. Instead, foreign investors have pushed local business players, especially small and medium enterprises, out of the market. -

Australia and Indonesia Current Problems, Future Prospects Jamie Mackie Lowy Institute Paper 19

Lowy Institute Paper 19 Australia and Indonesia CURRENT PROBLEMS, FUTURE PROSPECTS Jamie Mackie Lowy Institute Paper 19 Australia and Indonesia CURRENT PROBLEMS, FUTURE PROSPECTS Jamie Mackie First published for Lowy Institute for International Policy 2007 PO Box 102 Double Bay New South Wales 2028 Australia www.longmedia.com.au [email protected] Tel. (+61 2) 9362 8441 Lowy Institute for International Policy © 2007 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part Jamie Mackie was one of the first wave of Australians of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including but not limited to electronic, to work in Indonesia during the 1950s. He was employed mechanical, photocopying, or recording), without the prior written permission of the as an economist in the State Planning Bureau under copyright owner. the auspices of the Colombo Plan. Since then he has been involved in teaching and learning about Indonesia Cover design by Holy Cow! Design & Advertising at the University of Melbourne, the Monash Centre of Printed and bound in Australia Typeset by Longueville Media in Esprit Book 10/13 Southeast Asian Studies, and the ANU’s Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. After retiring in 1989 he National Library of Australia became Professor Emeritus and a Visiting Fellow in the Cataloguing-in-Publication data Indonesia Project at ANU. He was also Visiting Lecturer in the Melbourne Business School from 1996-2000. His Mackie, J. A. C. (James Austin Copland), 1924- . publications include Konfrontasi: the Indonesia-Malaysia Australia and Indonesia : current problems, future prospects. -

The Social Economic and Environmental Impacts of Trade

Journal of Business and Economics, ISSN 2155-7950, USA February 2021, Volume 12, No. 2, pp. 183-199 DOI: 10.15341/jbe(2155-7950)/02.12.2021/009 © Academic Star Publishing Company, 2021 http://www.academicstar.us The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Macroeconomic Resilience and Solution Steps Untung Lasiyono (Faculty of Economics and Business, University of PGRI ADI BUANA Surabaya, Indonesia) Abstract: This article describes the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on macroeconomic resilience and steps to solve it in Indonesia. The fact that is the problem is that this pandemic causes a threat to human life, so the Indonesian government makes policies so that human lives that are at risk can be saved. However, with this government policy there is an impact, namely the existence of restrictions on human activities including work activities, so that the absence of human work will result in loss of income and the effect of weakening the macro economy in Indonesia. The economies affected by the pandemic were rising inflation, weakening trade balance, weakening interest rates, decreasing foreign exchange, increasing unemployment. Seeing the weakening of the economy, steps that need to be taken are improving the community-based economic system, empowering micro, small and medium enterprises, empowering cooperative business entities, optimizing the use of natural resources and mastering information technology in the economic system, micro, small and medium enterprises and cooperatives. Key words: Covid-19, macroeconomic resilience JEL codes: D 1. Introduction In developments in Indonesia, COVID-19 has started to emerge since February until now it still shows a significant increase because it spreads to almost all provinces in Indonesia and data from the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia shows that Indonesia’s population has tested positive and died from COVID-19. -

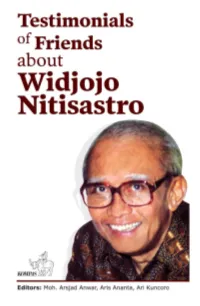

Prof. Dr. Widjojo Nitisastro

Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, Januari 2008 Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Publishing by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, Januari 2008 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70008004 Translated: Harry Bhaskara Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editors: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. Rahmawanta Cover foto by: family document All rights reserved. -

Asia Pacific Bulletin

Asia Pacific Bulletin Number 42 | August 17, 2009 The United States-Indonesia Comprehensive Partnership and the New Yudhoyono Administration BY THOMAS B. PEPINSKY Indonesia’s July 2009 presidential election confirmed that Indonesia has joined the ranks of the world’s consolidated democracies. Indonesia’s popular incumbent president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (known locally as SBY), appears to have easily won a Thomas B. Pepinsky, second term in office. As SBY prepares for his second term, the United States and assistant professor of Indonesia are planning a new “comprehensive partnership” to strengthen bilateral government at Cornell relations. At the same time, Indonesia faces a number of challenges—among them, the acute challenge of a global economic crisis, the chronic challenges of administering a University, explains that “All large and diverse developing country, and the renewed threat of terrorism—that will signs indicate that Susilo test SBY’s administration. SBY’s responses to these challenges will shape the course of Bambang Yudhoyono’s future U.S.-Indonesian bilateral relations. All signs indicate that SBY’s platforms for pursuing economic development, reform, and security at home are just right for forging platforms for pursuing Indonesia’s new partnership with the United States. economic development, reform, and security at home The global economic crisis has mostly spared Indonesia, due in no small part to Indonesia’s large internal markets and its relative insulation from toxic loans. Yet its are just right for forging economy still faces significant economic hurdles. Indonesia’s central bank, Bank Indonesia’s new partnership Indonesia, estimates that first quarter 2009 exports plummeted 30% from first quarter with the United States.” 2008, and that investment will grow only marginally in 2009 after several years of double-digit growth. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Berantas

The London School of Economics and Political Science Berantas Korupsi: A Political History of Governance Reform and Anti-Corruption Initiatives in Indonesia 1945-2014 Vishnu Juwono A Thesis Submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, May 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of words <98,911> words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Mrs. Demetra Frini 2 Abstract This thesis examines the efforts to introduce governance reform and anti-corruption measures from Indonesia‘s independence in 1945 until the end of the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono‘s (SBY‘s) presidency in 2014. It is divided into three main parts covering Sukarno‘s ‗Old Order‘, Suharto's ‗New Order‘, and the reform period. -

No. 277 Explaining the Trajectory of Golkar's Splinters in Post-Suharto Indonesia Yuddy Chrisnandi and Adhi Priamarizki S. Ra

The RSIS Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed in this publication are entirely those of the author(s), and do not represent the official position of RSIS. If you have any comments, please send them to [email protected]. No. 277 Explaining the Trajectory of Golkar’s Splinters in Post-Suharto Indonesia Yuddy Chrisnandi and Adhi Priamarizki S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 17 July 2014 ABOUT RSIS The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous school within the Nanyang Technological University. Known earlier as the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies when it was established in July 1996, RSIS‘ mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia Pacific. To accomplish this mission, it will: Provide a rigorous professional graduate education with a strong practical emphasis Conduct policy-relevant research in defence, national security, international relations, strategic studies and diplomacy Foster a global network of like-minded professional schools GRADUATE PROGRAMMES RSIS offers a challenging graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. The Master of Science degree programmes in Strategic Studies, International Relations, Asian Studies, and International Political Economy are distinguished by their focus on the Asia Pacific, the professional practice of international affairs, and the cultivation of academic depth. Thus far, students from more than 50 countries have successfully completed one of these programmes. In 2010, a Double Masters Programme with Warwick University was also launched, with students required to spend the first year at Warwick and the second year at RSIS.