Pre-Colonial Elitism: a Study in Traditional Model of Governance in Akokoland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

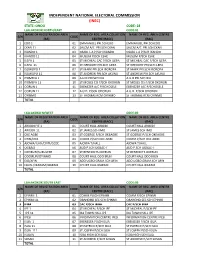

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

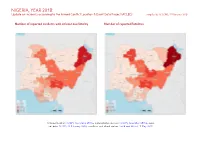

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 22 February 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 705 566 2853 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 474 373 2470 Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 2 Protests 427 3 3 Riots 213 61 154 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 117 3 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 100 84 759 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 2036 1090 6243 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). 2 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

Land Accessibility Characteristics Among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 2(1): 1-12, 2017; Article no.ARJASS.30086 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Land Accessibility Characteristics among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria Gbenga John Oladehinde 1* , Kehinde Popoola 1, Afolabi Fatusin 2 and Gideon Adeyeni 1 1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out collaboratively by all authors. Author GJO designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KP and AF supervised the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches while author GA led and managed the data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2017/30086 Editor(s): (1) Raffaela Giovagnoli, Pontifical Lateran University, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano 4, Rome, Italy. (2) Sheying Chen, Social Policy and Administration, Pace University, New York, USA. Reviewers: (1) F. Famuyiwa, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (2) Lusugga Kironde, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17570 Received 16 th October 2016 Accepted 14 th January 2017 Original Research Article st Published 21 January 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The study investigated challenges of land accessibility among migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. Methodology: Data were obtained through questionnaire administration on a Migrant household head. Multistage sampling technique was used for selection of 161 respondents for the study. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Integrated Geophysical Investigation of a Suspected Spring in Igbokoran, Ikare-Akoko, Southwestern Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics (IOSR-JAGG) e-ISSN: 2321–0990, p-ISSN: 2321–0982.Volume 3, Issue 5 Ver. I (Sep. - Oct. 2015), PP 83-91 www.iosrjournals.org Integrated Geophysical Investigation of a Suspected Spring in Igbokoran, Ikare-Akoko, Southwestern Nigeria Onoja S.O1, Osifila A.J2, 1(Department of Physics, kogi State University Anyigba,Nigeria) 2(Department of Applied Geophysics, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria) Abstract: An integrated geophysical investigation involving self potential (SP), very low frequency electromagnetic (VLF-EM) and electrical resistivity methods (VES) were conducted around a suspected spring in Igbokoran, Ikare Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria in other to understand the nature of the spring as well as evaluate the feasibility of ground water development in the area. Three geophysical traverses of length 240m each were established in the study area in approximately E-W direction. VLF-EM measurements with station spacing of 10m was used as reconnaissance to delineate conductive zones between 70-160m along traverse 1, 80-170 m along traverse 2 and 60-180m along traverse 3.This was then followed by a total of six (6) VES stations along traverses 2 and 3 using the Schlumberger array with electrode spacing (AB/2) ranging from 1 to 150m. Three geoelectric layers (Top layer, weathered layer, and fresh basement) were delineated along all traverses and a suspected fractured basement along traverse three .The Self Potential (SP) measurements were carried out at 5m electrode separation employing the total fixed base array. SP profiles were generated which show anomalies with short negative amplitudes some of which coincides with the spring zone. -

The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Media Adverts

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 4, No. 2; 2014 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Media Adverts Joseph Babasola Osoba1 1 Department of English, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria Correspondence: Joseph Babasola Osoba, Department of English, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: November 27, 2013 Accepted: February 1, 2014 Online Published: March 26, 2014 doi:10.5539/ijel.v4n2p26 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v4n2p26 Abstract The use of Nigerian Pidgin seems to have gained a wider currency since Nigeria’s independence in 1960. Among the educated and barely educated, the pidgin is used profusely in many spheres of life, especially in informal situations. In the mass media (television, radio, magazines and newspapers), schools, higher institutions of learning, government offices, etc., pidgin discourse abounds. In fact, despite the fact that it is not yet an official lingua franca in the country, it is a daily phenomenon in every day affair of an average Nigerian. The nature of Nigerian Pidgin, its easy mode of acquisition as well as the multilingual background of Nigerians may have been responsible for its present status and functions. In the light of the above, I am interested in how meaning is assigned to a piece of pidgin discourse, especially an advert in Nigerian Pidgin. Thus the goal of this paper is to establish how pidgin adverts communicate the intended meaning of their advertisers and how the audiences perceive them through an application of “Presupposition” and “Implicature” as conceptual or theoretical tools. -

The Sahel and West Africa Club

2011 – 2012 WORK PRIORITIES GOVERNANCE THE CLUB AT A GLANCE SAHEL AND WEST AFRICA Club he Strategy and Policy Group (SPG) brings together Club Members twice a year Secretariat 1973. Extreme drought in the Sahel; creation of the “Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Food security: West African Futures Tto defi ne the Club’s work priorities and approve the programme of work and Control in the Sahel” (CILSS). The Club’s work focuses on settlement trends and market dynamics, analysing how budget as well as activity and fi nancial reports. Members also ensure the Club’s these two factors impact agricultural activities and food security conditions in smooth functioning through their fi nancial contributions (minimum contribution 1976. Creation of the “Club du Sahel” at the initiative of CILSS and some OECD member countries aiming West Africa. Building on a literature review and analyses of existing information, agreed upon by consensus) and designate the Club President. The position is at mobilising the international community in support of the Sahel. it questions the coherence of data currently used for policy and strategy design. It currently held by Mr. François-Xavier de Donnea, Belgian Minister of State. Under Secrétariat du also highlights the diffi culty of cross-country comparisons, which explains why the management structure of the OECD Secretariat for Global Relations, the SWAC THE SAHEL 1984. Another devastating drought; creation of the “Food Crisis Prevention Network” (RPCA) at the DU SAHEL ET DE it is almost impossible to construct a precise description of regional food security Secretariat is in charge of implementing the work programme. -

Hydro-Geochemical Evaluation of Groundwater Quality in Akoko North West Local Government Area of Ondo State, Nigeria

ISSN = 1980-993X – doi:10.4136/1980-993X www.ambi-agua.net E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (12) 3625-4212 Hydro-geochemical evaluation of groundwater quality in Akoko North West local government area of Ondo State, Nigeria (http://dx.doi.org/10.4136/ambi-agua.851) Temitope D. T. Oyedotun1; Opeyemi Obatoyinbo2 1Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, P. M. B. 001, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected]; 2Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, Adekunle Ajasin University, P. M. B. 001, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT A sudden geometric increase in population of Akoko North West Local Government Area of Ondo State has led to an increase in demand for water and harnessing of subsurface water reserve. A total of twenty six water samples obtained from both boreholes and hand-dug wells were analyzed for their physico-chemical characteristics with the aim of assessing their quality, usability and also to determine the level of their contamination in the local government which is dominated by granite gneisses, charnockites, and augen gneisses as the main rock types. The following physico-chemical properties were analyzed for in the samples collected: electrical conductivity (EC), pH, total alkalinity (TA), total dissolved solids (TDS), total suspended solids (TSS), acid neutralizing capacity (ANC) with major cations (Na+, 2+ 2+ 3- - 3- 2+ 2+ + + Mg , Ca ), anions (PO4 , HCO3 , SO4 ) and several heavy metals -

Print This Article

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 3 No. 4; July 2014 Copyright © Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Lexical Variation in Akokoid Fádorò, Jacob Oludare Department of Linguistics and African Languages, University of Ibadan, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Received: 15-02- 2014 Accepted: 01-04- 2014 Published: 01-07- 2014 doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.3n.4p.198 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.3n.4p.198 Abstract Language contact among Akokoid, Yoruboid and Edoid has resulted in extensive borrowing from Yoruboid and Edoid to Akokoid. Thus, the speech forms subsumed under Akokoid exhibit lexical items which are similar to Yoruboid and Edoid. To the best of our knowledge, no other scholarly work has addressed the concept ‘lexical variation in these speech forms, hence, the need for this present effort. Twenty lexical items were carefully selected for analysis in this paper. Data were elicited from 34 informants who are competent speakers of Akokoid. Apart from the linguistic data, these informants, including traditional rulers, supplied us with historical facts about the migration patterns of the progenitors of Akokoid. The historical facts coupled with the linguistic data helped us to arrive at the conclusion that some of the words used in contemporary Akokoid found their way into Akokoid as a result of the contact between Akokoid and their neighbours, Yoruboid and Edoid. Keywords: Akokoid, Language Contact, Lexical Variation, Yoruboid, Edoid 1. Introduction 1.1 The Sociolinguistic Situation in Akokoid As hinted in Fadọrọ $, 2010 & 2012, Akoko is the most linguistically diverse area of Yorùbáland. -

Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 9, No. 4, 2013, pp. 23-29 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020130904.2598 www.cscanada.org Yoruba Culture of Nigeria: Creating Space for an Endangered Specie Adepeju Oti[a],*; Oyebola Ayeni[b] [a]Ph.D, Née Aderogba. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. [b] INTRODUCTION Ph.D. Lead City University, Ibadan, Nigeria. *Corresponding author. Culture refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, Received 16 March 2013; accepted 11 July 2013 hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects Abstract and possessions acquired by a group of people in the The history of colonisation dates back to the 19th course of generations through individual and group Century. Africa and indeed Nigeria could not exercise striving (Hofstede, 1997). It is a collective programming her sovereignty during this period. In fact, the experience of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group of colonisation was a bitter sweet experience for the or category of people from another. The position that continent of Africa and indeed Nigeria, this is because the ideas, meanings, beliefs and values people learn as the same colonialist and explorers who exploited the members of society determines human nature. People are African and Nigerian economy; using it to develop theirs, what they learn, therefore, culture ultimately determine the quality in a person or society that arises from a were the same people who brought western education, concern for what is regarded as excellent in arts, letters, modern health care, writing and recently technology. -

Country School Name Level

List of Schools Eligible to Participate in TSL 2021 Debates Country School name Level Australia Manly Selective Campus NBSC Secondary Bangladesh Engineering University School and College Secondary Belarus School #71 of Minsk Primary School #1 named after M. M. Gruzhevsky Secondary School 151 Minsk Secondary Belgium European School Brussels 3 Secondary Bulgaria 128 SU 'Albert Einstein' Secondary PGT Asen Zlatarov Secondary Secondary School of Economics Georgi St. Rakovski Secondary Canada Island ConnectED K-12 School Secondary Paul Kane Secondary China Victoria Shanghai Academy Secondary Dominica Dominica Grammar School Secondary Egypt The International School of Elite Education Primary Alsadat Sec for Girls in Damro Secondary Bishbish Secondary common School Secondary El Gdeda Secondary School Secondary Ismailia STEM High School Secondary Obour STEM School Secondary Sharkia STEM School Secondary STEM Sharkia Secondary The International School of Elite Education Secondary Ghana Presbyterian Boys' Senior High School Secondary Tsito Senior High Technical School Secondary Greece Doukas School Secondary Honduras Alison Bixby Stone School Secondary India Aurum the Global School Primary & Secondary Dl. Dav Model School Primary & Secondary List of Schools Eligible to Participate in TSL 2021 Debates Ann Mary School Secondary Avasarshala Secondary Bharath Senior Secondary School Secondary Bhartiyam International School Secondary Bhavan Vidyalaya Secondary Hill Spring International School Secondary Individual Entry Secondary Jay Pratap Singh Public