Teaching Information Ethics in Library and Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About the Contributors

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS Michael Cross began his career as lecturer at the Faculty of Education, University of the Witwatersrand in 1986. He has been awarded teaching and research fellowships in several institutions including the Johns Hopkins University and North- western University. He was a visiting scholar at Stanford University, Stockholm University and Jules-Vernes University in Amiens. Winner of the 1911–12 award as most Outstanding Mentor of Educational Researchers in Africa from the Association for Educational Development in Africa (ADEA), Professor Cross is author and co- author of several books, book chapters and numerous articles in leading scholarly journals. He has served as an education specialist in several major national education policy initiatives in South Africa, such as the National Commission on Higher Education and the Technical Committee on Norms and Standards for Educators. He is currently the Director of the Ali Mazrui Centre for Higher Education Studies at the University of Johannesburg. James Otieno Jowi is the founding Executive Director/Secretary General of the African Network for Internationalization of Education (ANIE), an African network focused on the international dimension of higher education in Africa. He heads the ANIE Secretariat based at Moi University, Kenya, and is responsible for the implementation of ANIE activities. He also teaches Comparative and International Education at the School of Education, Moi University. He has published on internationalization of higher education, governance, management and leadership in higher education. He was member of the IAU Task Force on the 3rd and 4th Global Surveys on Internationalization of Higher Education. He is also a member of the IAU Ad-hoc Expert Group on Rethinking Internationalization. -

Gender Center and Gender Mainstreaming

Gender Center and Gender Mainstreaming Educational level: University | Beneficiaries: Students, faculty, and staff Background Assessments of universities such as Jimma University1 and the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM)2 that found sexual harassment and violence and high attrition of female students played a role in developing gender centers.1 At the University of Western Cape, campus activism on issues including gender imbalances in salary and career development, sexual harassment, and maternity leave and child care contributed to the creation of a gender center.3 In other institutions, national and institutional commitment was key. For example, one of the objectives of the Presidential Working Party to establish Moi University was to develop a gender center, and the university’s 2005-2014 strategic plan committed to incorporating gender issues in policy decision-making processes.4 Makerere University also enjoyed a supportive national legislative environment in Uganda.5 Description Many institutions, including Jimma University, Moi University, UDSM, and Makerere University, note the role of the gender centers in promoting gender mainstreaming. The gender centers, offices, and committees at the institutions included in this review shared some common functions, including gender equality-related policy development, provision of training, skills-building, mentoring, counseling services, networking, information sharing, and research. Some institutions also provide scholarships to female students (Jimma University,6 Makerere University,5 University of Toronto7); facilitate housing for female faculty (Jimma University,6 University of Western Cape3); develop curricula on gender-related issues (the University of Ghana8); and develop proposals for “gender sensitive infrastructure within the University”9 (Sokoine University of Agriculture). The University of Toronto has multiple offices that work on diversity and equity issues. -

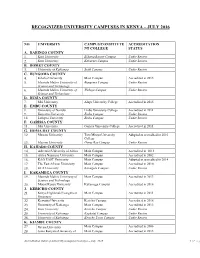

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Registered Participant List

AORTIC 2019 Registered Participant List ~As of 1 November 2019~ First Name Last Name Organisation Country Kunuz Abdella American Cancer Society Ethiopia Fatimah Abdulkareem College of Medicine University of Lagos Nigeria Habiba Ibrahim Abdullahi University of Abuja Teaching Hospital Nigeria Christian Abnet National Cancer Institute United States Natasha Abraham National Cancer Registry South Africa Mustapha Abubakar National Cancer Institute United States Dafalla Omer Elmustafa Abuidris Gezira University Sudan Emmah Achieng AMPATH Kenya Esther Serwaa Ackah Roche Products Ghana Ghana Briony Ackroyd Malawi College of Medicine United Kingdom Abdullahi Adamu Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital Nigeria Danladi Adamu Gombe State University | University of Edinburgh United Kingdom Adebola Adedimeji Albert Einstein College of Medicine United States Babatunde Adedokun University of Chicago United States Ayodeji Adefemi Lagos State University Teaching Hospital Nigeria Bolanle Comfort Adegboyega Lagos University Teaching Hospital Nigeria Prisca Adejumo University of Ibadan Nigeria Taiwo Adegbola Adejuyigbe Dynamicgoogleintr Nigeria Adenike Adeniji-Sofoluwe University of Ibadan Nigeria Henry Adeola University of Cape Town South Africa Adekunle Adesina Baylor College of Medicine United States Margaret Adhiambo AIC Kijabe Hospital Kenya Amalia Adler-Waxman Teva Pharmaceuticals Israel Kasimu Adoke Government Nigeria Ben Adusei 37 Military Hospital Ghana Melhaoui Adyl Centre National de Réhabilitation Morocco Ilir Agalliu Albert Einstein College -

Research Article the Challenges of Student Affairs at Kenyan Public Universities

Journal of Student Affairs in Africa | Volume 1 (1&2) 2013, 33–48 | ISSN 2307-6267 | DOI: 10.14426/jsaa.v1i1-2.34 research article The challenges of student affairs at Kenyan public universities Tamara Yakaboski* and Matthew Birnbaum** Abstract Kenya is increasingly turning to the promise of mass higher education to help solve a range of economic and social issues. These efforts have had profound effects on university students, faculty and professionals who provide the vital student support services necessary for academic success. This case study explores the challenges that face Kenyan student services professionals within the context of the country’s history and cultures. Kenya’s student service professionals face four major challenges: the increasing costs of attendance, the resulting impact on student behaviours and actions, lack of training and senior leadership, and regular campus closures. Keywords student affairs, accommodation, student housing, student services, university environment, higher education. The challenges of student affairs at Kenyan public universities Kenya is increasingly turning to the promise of mass higher education, meaning a shift from an elite to an open system of access, to help solve a range of economic and social problems (Jowi, 2009; Kenya Vision 2030, 2007). The national government has made its commitment to post-secondary education evident through the addition of over 25 public universities and constituent colleges since 1994 and its adoption of policies encouraging rapid enrolment growth in nearly all post-secondary institutions. Between 2010 and 2013, Kenya made nearly 20 constituent colleges and branch campuses into stand-alone universities. Even with this growing capacity, Kenya’s demand for access to affordable higher education far exceeds the system’s ability to deliver quality instruction and student support (Ngolovoi, 2010; Owuor, 2012). -

Toward an Online Master of Public Health Degree in Kenya: Moi University’S Path

International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 2018, Vol. 14, Issue 1, pp. 17-32 Toward an online Master of Public Health degree in Kenya: Moi University’s path Peter Koskei and Rose Ruto-Korir Moi University, Kenya Carol Carrier and Gregory Sales University of Minnesota, USA ABSTRACT As higher education institutions around the world strive to ensure they remain relevant By meeting the needs of today’s digitally-focused students, the numBer of online courses and degree programs is increasing dramatically. Not surprisingly, given this trend, in recent years the School of Public Health at Moi University, in Eldoret, Kenya, has received inquiries from students across Kenya and the neighboring countries of Rwanda, Zambia, and Malawi about the availability of online courses. Recognizing the Benefits to Both potential students and the institution, SPH set a goal to join the trend to offer online courses. This article details SPH’s path toward that end. It discusses the rationale for this decision, examines the state of ICT in Africa in general and Kenya more specifically, the activities undertaken by SPH, resources that have Been devoted to the effort, progress made, challenges faced, and the status of the work to date. Keywords: Online Learning; Online MPH; Kenya; One Health; e-learning INTRODUCTION Officially inaugurated on DecemBer 6, 1985, Moi University has its main campuses in Eldoret, Kenya, was. Growing from a school of agriculture a little over 30 years ago, Moi University now has a total of 15 Schools, 9 Directorates and 2 Institutes. It currently serves more than 52,000 students (Moi University 2017). -

Unai Members List August 2021

UNAI MEMBER LIST Updated 27 August 2021 COUNTRY NAME OF SCHOOL REGION Afghanistan Kateb University Asia and the Pacific Afghanistan Spinghar University Asia and the Pacific Albania Academy of Arts Europe and CIS Albania Epoka University Europe and CIS Albania Polytechnic University of Tirana Europe and CIS Algeria Centre Universitaire d'El Tarf Arab States Algeria Université 8 Mai 1945 Guelma Arab States Algeria Université Ferhat Abbas Arab States Algeria University of Mohamed Boudiaf M’Sila Arab States Antigua and Barbuda American University of Antigua College of Medicine Americas Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Facultad Regional Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Universidad Abierta Interamericana Americas Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa Americas Argentina Universidad Católica de Salta Americas Argentina Universidad de Congreso Americas Argentina Universidad de La Punta Americas Argentina Universidad del CEMA Americas Argentina Universidad del Salvador Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cordoba Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de la Pampa Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Rosario Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de -

Awareness and Attitude of Undergraduates Toward Serial Publications in Kwara State University Library Qudus Bankole [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln May 2019 Awareness and Attitude of Undergraduates toward Serial Publications in Kwara State University Library Qudus Bankole [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Bankole, Qudus, "Awareness and Attitude of Undergraduates toward Serial Publications in Kwara State University Library" (2019). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 2438. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2438 AWARENESS AND ATTITUDE OF UNDERGRADUATES TOWARD SERIAL PUBLICATIONS IN KWARA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Abstract This study examined the awareness and attitude of undergraduates toward Serial Publications in Kwara State University Library. Descriptive survey research method was adopted and questionnaire was administered to 360 undergraduates of Kwara State university to obtain the required data. The objectives of the study were to ascertain the level of awareness of serials publications, the rate of serial accessibility, attitude of student towards serial publications, constraints faced in the use of serials and types of serials used by student and its influence on their academic performance. The result revealed that journals and newspapers are the mostly patronized types of serials by undergraduate students. More than half of the undergraduates have access to serial like journals, newspapers and government publications. Also fair size of the respondents attested that serial publications have positive impact on their academic performance to some extent. The study also revealed that the respondents have negative attitude toward serial publication in the library. The major constraint associated with the use of serial publications was inadequate infrastructure for accessing serials electronically and many of the serials are not well displayed in the library. -

'The Art & Science of Fundraising'

‘The Art & Science of Fundraising’ A Study Visit to New York for Executives from African Universities and Cultural Institutions New York City Funded through the generous support of List of participants in the 2013 to 2018 study visit programs (Titles and affiliations as of year of participation) Prof. Otlogetswe Totolo, Vice-Chancellor, Botswana International University of Science & Technology, Botswana, 2016 Prof. Thabo Fako, Vice-Chancellor, University of Botswana, Botswana, 2013 Mr. Dawid B. Katzke, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Finance & Administration, University of Botswana, Botswana, 2013 Dr. Baagi T. Mmereki, Director, University of Botswana Foundation, University of Botswana, Botswana, 2013 Ms. Pamela Khumbah, Director, Office of Advancement & Development, Catholic University Institute of Buea, Cameroon, 2016 Prof. Edward Oben Ako, Rector, University of Maroua, Cameroon, 2017 Ms. Djalita Fialho, Board Member, Pedro Pires Leadership Institute, Cape Verde, 2018 Amb. Honorat Emmanuel Koffi-Abeni, International Relations Advisor, MDE Business School (IHE-Afrique), Côte d'Ivoire, 2017 Mr. Didier Raux-Yao, Chief of Finance and Fundraising Officer, MDE Business School (IHE-Afrique), Côte d'Ivoire, 2017 Prof. Saliou Toure, President, International University of Grand-Bassam, Côte d'Ivoire, 2018 Mr. Samuel Koffi, Chief Operating Officer, International University of Grand-Bassam, Côte d'Ivoire, 2018 Ms. Ramatou Coulibaly-Gauze, Dir. of Admin. & Finance, International University of Grand-Bassam, Côte d'Ivoire, 2018 Prof. Léonard Santedi Kinkupu, Rector, Catholic University of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2017 Dr. Ese Diejomaoh, Projects Coordinator, Centre Congolais de Culture de Formation et de Développement, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2016 Ms. Nicole Muyulu, Nurse Educator & Hygienist, Centre Congolais de Culture de Formation et de Développement, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2016 Prof. -

Determinants of E-Services Use in Higher Education: a Case of a Kenyan University Academic and Non Academic Staff

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 2 No. 5 May 2014 Determinants of E-Services Use in Higher Education: A case of a Kenyan University Academic and Non Academic Staff Corresponding Author Edna J. M., University of Nairobi Email: [email protected] Gikandi J.W., Mt. Kenya University Email: [email protected] Solomon K. N., Moi University Email:[email protected] Key words: e-service, academic staff, non academic staff, constraints ABSTRACT The establishment of electronic services (e-services) has been an important policy goal in many universities worldwide. This notwithstanding, staff access to e-services and its reliability still remains an issue of concern that can hinder use of these services. The use of e-services in operational processes of teaching and administration can support staff to improve their work performance and promote competitive advantage for the university. However, many factors determine the use of e-services for staff in their day-to-day operations. This study is focused on towards academic and non academic staff of the University of Nairobi, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences (CAVS). Specifically, the aim was to identify the factors that determine e- services use. An empirical study was carried out whereby data was collected through a survey questionnaire administered face to face with a total of 100 academic and non academic staff users of e-services. The results were obtained from econometric modelling that is Logit regression. The evidence from staff in CAVS gave a set of factors that included staff characteristics and organizational constraining factors of e-services. -

Sessional Paper No………………

REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION, SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY SESSIONAL PAPER NO……………….. of 2012 A POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR EDUCATION AND TRAINING Reforming Education and Training in Kenya. TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFINITIONS OF TERMS .......................................................................................................... viii SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER ONE: BACKGROUND TO THE EDUCATION AND TRAINING SECTOR IN KENYA.......................................................................................................................................... 1 Basic Education ......................................................................................................................... 2 The Tertiary Sector .................................................................................................................... 2 The TIVET Sector...................................................................................................................... 3 Teacher Education, Development and Management. ................................................................ 3 Teacher Management ................................................................................................................. 3 University Education ................................................................................................................. 3 Kenya Qualifications Framework ............................................................................................. -

Introducing Icoe Real Periperi U Periperi U Approved As IRDR International Centre of Excellence IRDR - HQ Other Icoe Periperi U

Introducing ICoE REaL Periperi U Periperi U Approved as IRDR International Centre of Excellence IRDR - HQ Other ICoE Periperi U Academy of Sciences in Taipei, Taiwan VaRM -University of South Carolina, Columbia, USA UR & S - National University of Colombia, Colombia * Periperi U Consortium Joint Centre for Disaster Research - Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand * Periperi U Consortium: Bahir Dar University - Ethiopia, University of Science and Technology – Houari Boumediene - Algeria, Ardhi University – Tanzania, Makerere University – Uganda, University of Antananarivo – Madagascar, University of Ghana – Ghana, University of Gaston Berger – Senegal, Technical University of Mozambique – Mozambique, Moi University – Kenya, Ahmadu Bello University – Nigeria, University of Stellenbosch – South Africa An African Partnership of 11 HEIs 1. Bahir Dar Univ. 2.•Makerere? Conclusion Univ. slide 3. Moi Univ. 4. Ardhi Univ. 11 5. Technical Univ. Mozambique 6. Univ. of Antananarivo 7. Stellenbosch Univ. 8. Univ. of Ghana 9. Gaston Berger Univ. 10.Univ. Science & Technology Houari Boumediene 11. Ahmadu Bello Univ. … ‘virtual centre’ for DRM capacity building in Africa Periperi U Partner Staff Salary Periperi U Facts Sources Full Funding from USAID 11 African universities 26% 42% Partial Funding (USAID and University/ 168 core & adjunct staff external) Full funding from 32% University/ External 8 languages of instruction source Core and Adjunct staff, and total staff per partner 45 40 35 30 25 Core staff 20 15 Adjunct staff 10 Total staff 5 0 Logic Model for Purposive Engagement of HEIs Achievements Short Courses 57 2011-2014? Participants 1,417 Growing global Academic progs/modules 18 visibility & confidence in African scholarship Students registered 870 in this field.