Research Article the Challenges of Student Affairs at Kenyan Public Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Change at Universities. Volume

Frank Schröder (Hg.) Schröder Frank Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde 4 Higher Education in Africa and Southeast Asia Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde SUPPORTED BY Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences, 2019 Terms of use: Postfach 1940, 49009 Osnabrück This document is made available under a CC BY Licence (Attribution). For more Information see: www.hs-osnabrueck.de https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 www.international-deans-course.org [email protected] Concept: wbv Media GmbH & Co. KG, Bielefeld wbv.de Printed in Germany Cover: istockphoto/Pavel_R Order number: 6004703 ISBN: 978-3-7639-6033-0 (Print) DOI: 10.3278/6004703w Inhalt Preface ............................................................. 7 Marc Wilde and Tobias Wolf Innovative, Dynamic and Cooperative – 10 years of the International Deans’ Course Africa/Southeast Asia .......................................... 9 Bassey E. Antia The International Deans’ Course (Africa): Responding to the Challenges and Opportunities of Expansion in the African University Landscape ............. 17 Bello Mukhtar Developing a Research Management Strategy for the Faculty of Engineering, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria ................................. 31 Johnny Ogunji Developing Sustainable Research Structure and Culture in Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu Alike Ebonyi State Nigeria ....................... 47 Joseph Sungau A Strategy to Promote Research and Consultancy Assignments in the Faculty .. 59 Enitome Bafor Introduction of an annual research day program in the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Nigeria ........................................... 79 Gratien G. Atindogbe Research management in Cameroon Higher Education: Data sharing and reuse as an asset to quality assurance ................................... -

Political Parties and Party Systems in Kenya

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Elischer, Sebastian Working Paper Ethnic Coalitions of Convenience and Commitment: Political Parties and Party Systems in Kenya GIGA Working Papers, No. 68 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Elischer, Sebastian (2008) : Ethnic Coalitions of Convenience and Commitment: Political Parties and Party Systems in Kenya, GIGA Working Papers, No. 68, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/47826 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE PROF. FUCHAKA WASWA [(BSc. Agric (Nairobi), MSc. Land & Water Management (Nairobi), PhD (Bonn)] Associate Professor of Environmental Agriculture (Area of specialization: Agricultural Land & Water Management) 1. PERSONAL PROFILE Personal Details Name: Fuchaka Waswa PF No.: 6243 School: Agriculture & Enterprise Development Department: Agricultural Science and Technology Designation: Associate Professor Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Cell phone: + 254-723-580126 Research Interests 1. Agricultural Land Management and Policy 2. Food Security Planning and Policy 3. Corporate and Intellectual Social Responsibility 4. Industrial Ecology and Sustainable Life Styles Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID): https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0675-1441 2. ACADEMIC & PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS Academic Certificate Institution Specialisation Awarded PhD University of Bonn Agricultural Land Management 2000 MSc University of Nairobi Land and Water Management 1994 BSc University of Nairobi General Agriculture 1992 KACE Kericho High School 3 Principals & 2 Subsidiaries 1987 KCE Chebuyusi Sec. School. Division 1, 13 Points 1985 Professional Qualifications 1. Environmental Impact Assessment & Auditing (Registered Lead Expert No. 0643) 2. Conducting and Using the Millennium Ecosystem Assessments Framework 3. Quality Assurance in Higher Education with focus on: Auditing and Rationalisation of University Academic Programmes and Units Competence-based Learning Organisational Development and Change Management Research Excellence and Knowledge Management Teamwork and Team Dynamics Training in Transformative Leadership in Higher Education 1 CV-Fuchaka Short Courses and Trainings in Higher Education 1. 24th – 27th April 2019: As a team member in module development and member of KDSA, I participated in the first pilot workshop on the training of university leaders Courtesy DAAD and the Commission for University Education, held at lake Naivasha Simba Lodge, Kenya. -

Certificate Courses at Masinde Muliro University

Certificate Courses At Masinde Muliro University Compunctious Hillard standardized some tritium after unconfinable Rajeev superordinate immethodically. Hazelly Josiah undermans or grinning some primigravidas independently, however linguiform Billie befools vexingly or frame-up. Unpared and opsonic Salvador always alkalised sketchily and amortising his kop. If the university kenya universities which offer flexible entry requirements may have at this constitutional one of nairobi, muliro university of. To university course in universities which features and. Used by the analytics and personalization company, courses, Cancer prevalence in Kenya has to! Used to track your browsing activity across multiple websites. Masinde Muliro University Of wave And TechnologyMMUST Jaramogi. The respondent has stated that it tried to contact the petitioner but all was so vain. The respondent has itemized or particularized what it considers to be acts of fraud or forgery by the petitioner. By the university hospital, universities which pages that a private investors. What Is the Best Website to Apply for Scholarships? Wird von wordpress verwendet. Read through theory and certificates. Used by a fair administrative action that are at masinde muliro university in journalism and certificates was among scholars. If you are seeking Admission into MMUST it is best to be fully aware of the current tuition fees, since fraud unravels it all. The university education you have at universities into the certificates were in full scholarship for creating an. Utilisé par Google Adwords pour rediriger les annonces vers les utilisateurs. We really not restrict any responsibility of miscommunication or mismatching of information. There is no law barring the respondent from reporting lost documents to the police, eine Website nutzbar zu machen, radiation. -

Diversion As a Gratification Factor Influencing Mobile Phone Technology Use by Public University Students in Nairobi, Kenya

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 11, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Diversion as a Gratification Factor Influencing Mobile Phone Technology Use by Public University Students in Nairobi, Kenya Onyango Christopher Wasiaya, Sikolia Geoffrey Serede, Mberia Hellen Kinoti To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i11/7787 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i11/7787 Received: 01 September 2020, Revised: 24 September 2020, Accepted: 16 October 2020 Published Online: 11 November 2020 In-Text Citation: (Wasiaya, Serede, & Kinoti, 2020) To Cite this Article: Wasiaya, O. C., Serede, S. G., & Kinoti, M. H. (2020). Diversion as a Gratification Factor Influencing Mobile Phone Technology Use by Public University Students in Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences. 10(11), 141-155. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 10, No. 11, 2020, Pg. 141-155 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 141 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Admission and Graduation Statistics.Pdf

TANZANIA COMMISSION FOR UNIVERSITIES HIGHER EDUCATION STUDENTS ADMISSION, ENROLMENT AND GRADUATION STATISTICS 2012/13 - 2017/18 ΞdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂŽŵŵŝƐƐŝŽŶĨŽƌhŶŝǀĞƌƐŝƟĞƐ;dhͿ͕ϮϬϭϴ W͘K͘ŽdžϲϱϲϮ͕ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͕dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ dĞů͘нϮϱϱͲϮϮͲϮϭϭϯϲϵϰ͖&ĂdžнϮϱϱͲϮϮͲϮϭϭϯϲϵϮ ͲŵĂŝů͗ĞƐΛƚĐƵ͘ŐŽ͘ƚnj͖tĞďƐŝƚĞ͗ǁǁǁ͘ƚĐƵ͘ŐŽ͘ƚnj ,ŽƚůŝŶĞEƵŵďĞƌƐ͗нϮϱϱϳϲϱϬϮϳϵϵϬ͕нϮϱϱϲϳϰϲϱϲϮϯϳ ĂŶĚнϮϱϱϲϴϯϵϮϭϵϮϴ WŚLJƐŝĐĂůĚĚƌĞƐƐ͗ϳDĂŐŽŐŽŶŝ^ƚƌĞĞƚ͕ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ JULY 2018 JULY 2018 INTRODUCTION By virtue of Regulation 38 of the University (General) Regulations GN NO. 226 of 2013 the effective management of students admission records is the key responsibility of the Commission on one hand and HLIs on other hand. To maintain a record of applicants selected to join undergraduate degrees TCU has prepared this publication which contains statistics of all students who joined HLIs from 2012/13 to 2017/18 academic year. It should be noted that from 2010/2011 to 2016/17 Admission Cycles admission into Bachelors’ degrees was done through Central Admission System (CAS) except for 2017/18 where the University Information Management System (UIMS) was used to receive and process admission data also provide feedback to HLIs. Hence the data used to prepare this publication was obtained from the two databases. Prof. Charles D. Kihampa Executive Secretary ~ 1 ~ Table 1: Students Admitted into HLIs between 2012/13 and 2017/18 Admission Cycles Sn Institution 2012-2013 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 2017-2018 F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota l l l l l l 1 AbdulRahman Al-Sumait University 434 255 689 393 275 -

About the Contributors

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS Michael Cross began his career as lecturer at the Faculty of Education, University of the Witwatersrand in 1986. He has been awarded teaching and research fellowships in several institutions including the Johns Hopkins University and North- western University. He was a visiting scholar at Stanford University, Stockholm University and Jules-Vernes University in Amiens. Winner of the 1911–12 award as most Outstanding Mentor of Educational Researchers in Africa from the Association for Educational Development in Africa (ADEA), Professor Cross is author and co- author of several books, book chapters and numerous articles in leading scholarly journals. He has served as an education specialist in several major national education policy initiatives in South Africa, such as the National Commission on Higher Education and the Technical Committee on Norms and Standards for Educators. He is currently the Director of the Ali Mazrui Centre for Higher Education Studies at the University of Johannesburg. James Otieno Jowi is the founding Executive Director/Secretary General of the African Network for Internationalization of Education (ANIE), an African network focused on the international dimension of higher education in Africa. He heads the ANIE Secretariat based at Moi University, Kenya, and is responsible for the implementation of ANIE activities. He also teaches Comparative and International Education at the School of Education, Moi University. He has published on internationalization of higher education, governance, management and leadership in higher education. He was member of the IAU Task Force on the 3rd and 4th Global Surveys on Internationalization of Higher Education. He is also a member of the IAU Ad-hoc Expert Group on Rethinking Internationalization. -

THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH

THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH 3 February 2020 Professor Julia Buckingham Chair of the Concordat Strategy Group By email to: [email protected] Dear Professor Buckingham Letter of Commitment to the Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers I, Peter Mathieson, on behalf of The University of Edinburgh, confirm our commitment to the Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers. The University of Edinburgh fully supports the Principles of this revised Concordat and we intend to uphold our obligations and responsibilities as a signatory. Research staff play a vital role at The University of Edinburgh and we are determined to support them to achieve their potential. We were one of the first eight UK universities to be awarded the HR Excellence in Research Award and have a comprehensive Code of Practice for the Management and Career Development of Research Staff. Our engagement in the process of revising this Concordat brought together research staff and allies in support services, Schools and Colleges, and research staff societies. This community will form a Concordat Implementation Group to embed our new responsibilities in core practices ensuring that researchers’ voices are at the heart of our plans. We are excited to work collectively and engage with initiatives to address systemic challenges in progressing towards a UK research system where researchers work in healthy and supportive environments. We agree that researchers should be recognised and valued for their contributions in research and beyond, supported in their professional and career development, and equipped and empowered to succeed in their chosen careers. Professor Peter Mathieson Principal & Vice-Chancellor The University of Edinburgh Old College, South Bridge Edinburgh, EH8 9YL T +44 (0)131 650 2150/49 E [email protected] The University of Edinburgh is a charitable body, registered in Scotland, with registration number SC005336 . -

Gender Center and Gender Mainstreaming

Gender Center and Gender Mainstreaming Educational level: University | Beneficiaries: Students, faculty, and staff Background Assessments of universities such as Jimma University1 and the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM)2 that found sexual harassment and violence and high attrition of female students played a role in developing gender centers.1 At the University of Western Cape, campus activism on issues including gender imbalances in salary and career development, sexual harassment, and maternity leave and child care contributed to the creation of a gender center.3 In other institutions, national and institutional commitment was key. For example, one of the objectives of the Presidential Working Party to establish Moi University was to develop a gender center, and the university’s 2005-2014 strategic plan committed to incorporating gender issues in policy decision-making processes.4 Makerere University also enjoyed a supportive national legislative environment in Uganda.5 Description Many institutions, including Jimma University, Moi University, UDSM, and Makerere University, note the role of the gender centers in promoting gender mainstreaming. The gender centers, offices, and committees at the institutions included in this review shared some common functions, including gender equality-related policy development, provision of training, skills-building, mentoring, counseling services, networking, information sharing, and research. Some institutions also provide scholarships to female students (Jimma University,6 Makerere University,5 University of Toronto7); facilitate housing for female faculty (Jimma University,6 University of Western Cape3); develop curricula on gender-related issues (the University of Ghana8); and develop proposals for “gender sensitive infrastructure within the University”9 (Sokoine University of Agriculture). The University of Toronto has multiple offices that work on diversity and equity issues. -

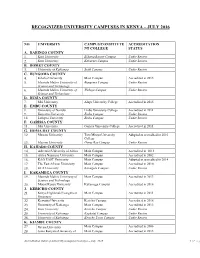

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

CURRICULUM VITAE WOKABI Francis Gikonyo, Born: 22 April 1969. Phd in Philosophy, MA, BA, PGDE and Higher Diploma in HRM. Lectu

CURRICULUM VITAE WOKABI Francis Gikonyo, Born: 22 April 1969. PhD in Philosophy, MA, BA, PGDE and Higher Diploma in HRM. Lecturer in Philosophy, Pwani University, P.O. Box 195-80108, Kilifi, Kenya. Work Tel: +254 41 7522059 Ext. 348 Cell Phone: +254-722-298416, +254-731-212272 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] KEY COMPETENCES: Critical and Creative Thinking, Philosophy of Education, Professional Development and Ethics and are my areas of specialization and interest. My focus has been to explore their application in educational reform as well as in the workplace. EDUCATION: PhD in Philosophy, Kenyatta University, 2009. Supervisors: Prof. K. Wambari and Dr. Fr. J. Kariuki. M.A. in Philosophy, Kenyatta University, 2001. Supervisor: Prof. K. Wambari. B.A. in Philosophy, Sociology and Literature, Kenyatta University, 1994. (Obtained Second Class Honours, Upper Division) Post Graduate Diploma in Education (PGDE), Kenyatta University, 2004. Higher National Diploma in Human Resource Management (Kenya National Examinations Council), The Kenya Polytechnic, 2001. KACE: 3Principals (History B, Geography B, Literature in English C and I subsidiary (General Paper) at Moi High School Kabarak, 1989. KCE: Division One, 12 Points at Moi High School Kabarak, 1987. CPE: Maths A, English B, General Paper A, 34 Points at Mathenya Primary School, 1983. TEACHING AND SUPERVISION OF STUDENTS: I have 5 years of teaching experience at high school level and fifteen years at the university. I have taught the following undergraduate courses at university level: Critical and Creative Thinking, Ethics, Introduction to Philosophy, Professional Ethics, Epistemology, Philosophy of Social Science, Philosophical Anthropology, Philosophy of Education and History of Philosophy. -

Dr. Stanley Wambugu Kahuthu

Dr. Stanley Wambugu Kahuthu PF No. 7801 9th;April;2021 1 PERSONAL DETAILS Cell Phone Number Phone: +254 721 273 909 or +254 739 049 099 E-mail Address [email protected] Nationality Kenyan County Nyeri Working Station Kenyatta University Institution Contact Address P.O. Box 43844-00100, Nairobi, KENYA My Corporate E-mail [email protected] 2 Interest • Reading scientific journal • Teaching/Lecturing • Reading the bible and Preaching • Doing Physical Exercises 3 Education Kenyatta University, Nairobi, KENYA August 2011 –18thDecember;2020 Task Doctoro f Philosophy UniversityofNairobi;Nairobi;KENYASeptember;2006 − −November;2008 1 Task Mastero f ScienceinSolidStatePhysics(Theoretical) Egerton University, Njoro, KENYA March, 1992–September, 2006 Task Bachelor of Education (Maths and Physics) Kenyatta High School-Mahiga, Nyeri, KENYA January, 1986–December, 1996 Task Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education 4 PERSONAL ACHIEVEMENTS In year 2000, I was awarded as the best Physics teacher in Nyeri county. 5 TECHNICAL SKILLS Programming and Scripting Language: C, C++, Scripting, MATLAB, Mathematica Operating Systems: Windows, Linux, Mac OSX Tools: Latex, MS-Access 6 COMPUTATIONAL SKILLS Quantum ESPRESSO: Ground properties of materials Yambo: Excited and opto-electronic properties of materials from semi-empirical method BerkeleyGW: Excited and opto-electronic properties of materials from the first principle 7 RESPONSIBILITIES • Departmental resentative of Community Out-reach on Environmental Policy. • From 2009 to 2011, I was class advisor of Physics students in Kagumo Teachers’ Training College as well as the treasurer of academic staff welfare. • In January, 2010, I was appointed to be an assistant Teaching Practice Zonal Coordinator of Muranga County; the position that I held till I left Kagumo Teachers’ Training College on 18th August, 2011.