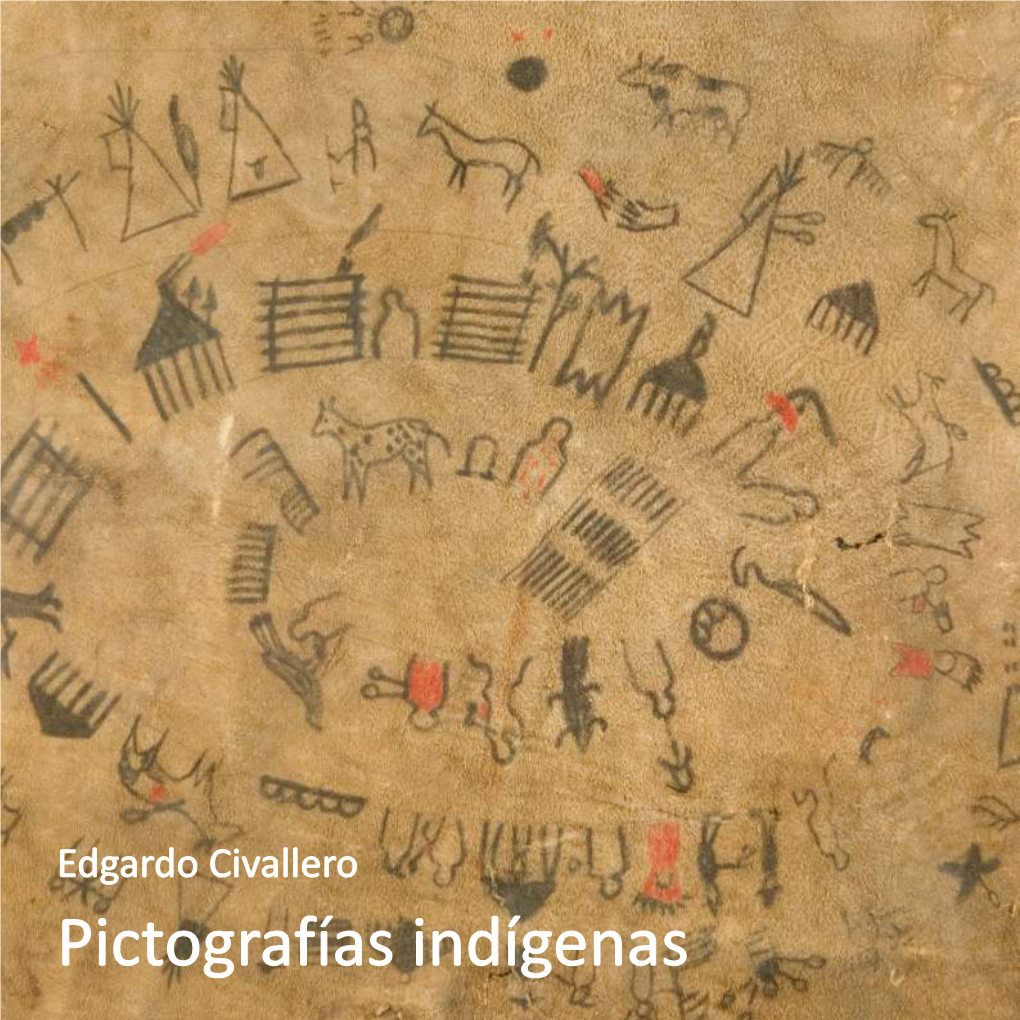

Edgardo Civallero Pictografías Indígenas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

187 1 Yale Deron Belanger a Thesis

Saulteaw land use within the Interîake Region of Manitoba: 1842- 187 1 BY Yale Deron Belanger A Thesis Submitted to the Department ofNative Studies and Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fdfïhent of the Requirements For the Degree of Interdiscipluiary Master of Arts in Native Studies At The University of Manitoba Department of Native Studies, Political Studies and Anthropology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba August 28,2000 O Yale Belanger National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*m of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtorr Ottawa ON Kl A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownenhip of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULT'Y -

June 2008 in the NEWS Anishinabek Nation Will Decide Who Are Citizens by Michael Purvis Citizenship

Volume 20 Issue 5 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 June 2008 IN THE NEWS Anishinabek Nation will decide who are citizens By Michael Purvis citizenship. Grand Council Chief John Sault Star The law proposes to do Beaucage said it’s time First There’s something troubling to several things, chief among them Nations start looking at citizenship Wayne Beaver about the high rate throwing out in the same way as nations like at which Alderville First Nation the concept Canada do. members are marrying people of status and “Right now we somewhat from outside the community. replacing buy into the aspect of status with It’s not the fact that youth are it with the Indian Act: Our membership looking to outsiders for mates citizenship clerks fi ll in the federal government that raises alarm bells — that’s akin to that forms and send them in to Ottawa expected, Beaver said, in a of the world’s and people get entered into a list,” community of just 300 people. sovereign Wayne Beaver said Beaucage. The problem is, if what the nations. “Well, once we have our studies say is true, Alderville “Under the present defi nition, citizenship law, we’re not going faces a future without any status the grandchildren of women such to do that; we’re not going to fi ll Indians as long as the federal as me, who marry non-Indians, those forms in and send them in Barack Black Eagle government’s defi nition of Indian will lose their status,” said to Ottawa.” MISSOULA, Mt.– Democratic party presidential candidate Barack status continues to hold sway, he Corbiere-Lavell. -

History7 Enhancements

NELSON HISTORY7 ENHANCEMENTS AUTHOR AND ADVISOR TEAM Stan Hallman-Chong James Miles Jan Haskings-Winner Deneen Katsitsyon:nio Montour, Charlene Hendricks Rotinonhsyón:ni, Kanyen’kehaka (Mohawk Nation), Turtle Clan, Heidi Langille, Nunatsiavutmiut Six Nations of the Grand River Territory Dion Metcalfe, Nunatsiavutmiut Kyle Ross Benny Michaud,DRAFT Métis Nation SAMPLE REVIEWERS Jan Beaver, Zaawaakod Aankod Kwe, Yellow Cloud Woman, Bear Clan, Alderville First Nation Dr. Paige Raibmon, University of British Columbia A special thank you to our Authors, Advisors, and Reviewers for sharing their unique perspectives and voices in the development of these lessons. Nelson encourages students to work with their teachers as appropriate to seek out local perspectives in their communities to further their understanding of Indigenous knowledge. TABLE OF Nelson History7 Enhancements CONTENTS Authors and Advisors Stan Hallman-Chong Benny Michaud Jan Haskings-Winner James Miles Charlene Hendricks Deneen Katsitsyon:nio Montour Heidi Langille Kyle Ross Dion Metcalfe UNIT 1: NEW FRANCE AND BRITISH NORTH Reviewers Jan Beaver AMERICA: 1713-1800 Dr. Paige Raibmon What Were the Spiritual Practices and Beliefs of The lessons in this resource have been written and developed Indigenous Peoples? 2 with Indigenous authors, educators, and advisors, and are to be What Is the Significance of the Covenant Chain, used with Nelson History7. Fort Stanwix, and British–Inuit Treaties? 10 Senior Publisher, Social Studies Senior Production Project Manager Cover Design Paula -

Two Late Woodland Midewiwin Aspects from Ontario

White Dogs, Black Bears, and Ghost Gamblers: Two Late Woodland Midewiwin Aspects from Ontario JAMES B. BANDOW Museum of Ontario Archaeology, University of Western Ontario INTRODUCTION Historians and ethnographers have debated the antiquity of the Midewiwin. Entrenched in historical discourse is Hickerson’s (1962, 1970) theory that the Midewiwin was a recent native resistance movement, a socio-evolutionary response to the changing culture patterns resulting from culture contact with Europeans. Other scholars view the Midewiwin as a syncretism, suggesting that a prehistoric component became intertwined with Christian influences that resulted in the ceremonial practices observed by ethnohistorians (Mason 2009; Aldendefer 1993; Dewdney 1975; Landes 1968). Recent critiques, however, provide evidence from material culture studies and center on the largely Western bias inherent in Hickerson’s diffusionist argument surrounding the post-contact origin of the Midewiwin. These arguments note structural similarities observed in birch bark scroll depictions, rock paintings and pictographs with historical narratives, ethnographic accounts, and oral history. These multiple perspectives lead some historians to conclude the practice was a pre-contact phenomenon (e.g., Angel 2002:68; Peers 1994:24; Schenck 1997:102; Kidd 1981:43; Hoffman 1891:260). Archaeological and material culture studies may provide further insight into understanding the origins of the Midewiwin. Oberholtzer’s (2002) recent overview of dog burial practices, for instance, compared prehistoric ritual patterns with the known historical practices and concluded that the increased complexity of the Midewiwin Society is an elaboration of substantive indigenous practices that must predate any European influence. This paper documents the archaeological continuity and syncretism of Mide symbolism observed from the Great Lakes region. -

Ojibwe and Dakota Relations: a Modern Ojibwe Perspective Through

Ojibwe miinawa Bwaanag Wiijigaabawitaadiwinan (Ojibwe and Dakota Relations) A Modern Ojibwe Perspective Through Oral History Ojibwe miinawa Bwaanag Wiijigaabawitaadiwinan (Ojibwe and Dakota Relations) A Modern Ojibwe Perspective Through Oral History Jason T. Schlender, History Joel Sipress, Ph.D, Department of Social Inquiry ABSTRACT People have tried to write American Indian history as the history of relations between tribes and non-Indians. What is important is to have the history of the Ojibwe and Dakota relationships conveyed with their own thoughts. This is important because it shows the vitality of Ojibwe oral history conveyed in their language and expressing their own views. The stories and recollections offer a different lens to view the world of the Ojibwe. A place few people have looked at in order to understand the complicated web of relationships that Ojibwe and Dakota have with one another. Niibowa bwaanag omaa gii-taawag. Miish igo gii-maajinizhikawaawaad iwidi mashkodeng. Mashkodeng gii-izhinaazhikawaad iniw bwaanan, akina. Miish akina imaa Minisooding gii-nagadamowaad mitigokaag, aanjigoziwaad. Mii sa naagaj, mii i’iw gaa- izhi-zagaswe’idiwaad ingiw bwaanag, ingiw anishinaabeg igaye. Gaawiin geyaabi wii- miigaadisiiwag, wiijikiwendiwaad. A lot of Sioux lived here. Then they chased them out to the prairies, all of them. They [were forced] to move and abandon the forests there in Minnesota. But later on, they had a [pipe] ceremony, the Sioux and Chippewa too. They didn’t fight anymore, [and] made friends.1 Introduction (Maadaajimo) There is awareness of a long history, in more modern times, a playful lack of trust between the Ojibwe and Dakota. Historians like William Warren documented Ojibwe life while Samuel Pond did the same with the Dakota. -

![People of the Three Fires: the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan.[Workbook and Teacher's Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7487/people-of-the-three-fires-the-ottawa-potawatomi-and-ojibway-of-michigan-workbook-and-teachers-guide-1467487.webp)

People of the Three Fires: the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan.[Workbook and Teacher's Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 321 956 RC 017 685 AUTHOR Clifton, James A.; And Other., TITLE People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan. Workbook and Teacher's Guide . INSTITUTION Grand Rapids Inter-Tribal Council, MI. SPONS AGENCY Department of Commerce, Washington, D.C.; Dyer-Ives Foundation, Grand Rapids, MI.; Michigan Council for the Humanities, East Lansing.; National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-9617707-0-8 PUB DATE 86 NOTE 225p.; Some photographs may not reproduce ;4011. AVAILABLE FROMMichigan Indian Press, 45 Lexington N. W., Grand Rapids, MI 49504. PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides '.For Teachers) (052) -- Guides - Classroom Use- Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MFU1 /PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; *American Indian History; American Indians; *American Indian Studies; Environmental Influences; Federal Indian Relationship; Political Influences; Secondary Education; *Sociix- Change; Sociocultural Patterns; Socioeconomic Influences IDENTIFIERS Chippewa (Tribe); *Michigan; Ojibway (Tribe); Ottawa (Tribe); Potawatomi (Tribe) ABSTRACT This book accompanied by a student workbook and teacher's guide, was written to help secondary school students to explore the history, culture, and dynamics of Michigan's indigenous peoples, the American Indians. Three chapters on the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway (or Chippewa) peoples follow an introduction on the prehistoric roots of Michigan Indians. Each chapter reflects the integration -

The Prophecy of the Seven Fires of the Anishinaabe

The Prophecy of the Seven Fires of the Anishinaabe Then seven prophets appeared to the people. The First Prophet told the people that in the time of the First Fire they would leave their homes by the sea and follow the sign of the megis. They were to journey west into strange lands in search of a island in the shape of a turtle. This island will be linked to the purification of the earth. Such an island was to be found at the beginning and at the end of their journey. Along the way they would find a river connecting two large sweet water seas. This river would be narrow and deep as though a knife had cut through the land. They would stop seven times to create villages but they would know that their journey was complete when they found food growing on the water. If they did not leave, there would be much suffering and they would be destroyed. And they would be pursued and attacked by other nations along the way so they must be strong and ready to defend themselves. The Second Prophet told them they could recognize the Second Fire because while they were camped by a sweet water sea they would lose their direction and that the dreams of a little boy would point the way back to the true path, the stepping stones to their future. The Third Prophet said that in the Third Fire the Anishinabe would find the path to the lands prepared for them and they would continue their journey west to the place where food grows upon the water. -

NOVEMBER 2012 More Tinkering in Brief with Indian Act First Nations Citizens Are Once Called Outdated and Racist

Page 1 Volume 24 Issue 9 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 NOVEMBER 2012 More tinkering In Brief with Indian Act First Nations citizens are once called outdated and racist. Clarke served as chairman of the Senate again watching from the sidelines is a citizen of Muskeg Lake First Aboriginal Peoples Committee, in- as Canadian Parliamentarians de- Nation in Saskatchewan. troduced a self-government bill the bate what they think is best for The Act outlines the relation- same week as he retired from the them – this time in putting for- ship between Canada and its First Upper Chamber at the mandatory ward three legislative proposals to Nations peoples. It restricts the age of 75. eliminate the 136-year-old Indian power of band councils, governs Grand Council Chief Patrick Act. land use and housing on reserves, Wedaseh Madahbee was shaking Calling the act an "interna- and created a system of residential his head at the ongoing efforts of tional embarrassment," interim schools that historians say caused the Stephen Harper government to Russell Means, 72 Liberal leader Bob Rae introduced untold damage to aboriginal com- ignore First Nations input in deal- Russell C. Means, the Oglala Sioux who was one of the key a private member's bill that would munities across Canada. ing with their issues. American Indian Movement (AIM) leaders of the 71-day 1973 pro- eliminate and replace the law, Rae's proposal would give the “The Conservative govern- test at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, has died at the age of 72. -

Native People of Wisconsin Teacher's Guide

Revised and Expanded Native People of Wisconsin Teacher’s Guide and Student Materials Patty Loew ♦ Bobbie Malone ♦ Kori Oberle Welcome to the Native People of Wisconsin Teacher’s Guide and Student Materials DVD. This format will allow you to browse the guide by chapter. See the following sections for each chapter’s activities. Before You Read Activities Copyright Resources and References Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press Publishers since 1855 © 2016 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin Permission is granted to use the materials included on this disc for classroom use, either for electronic display or hard copy reproduction. For permission to reuse material for commercial uses from Native People of Wisconsin: Teacher’s Guide and Student Materials, 978-0-87020-749-5, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for- profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users. Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Society’s collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706. CD cover and splash page: The Whitebear family (Ho-Chunk) as photographed by Charles Van Schaick, ca. 1906, WHi 61207. CD Splash page, from left to right: Chief Oshkosh, Wisconsin Historical Museum 1942.59; Waswagoning Village, photo by Kori Oberle; girl dancing, RJ and Linda Miller, courtesy -

An Analysis of Traditional Ojibwe Civil Chief Leadership

An Analysis of Traditional Ojibwe Civil Chief Leadership A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Giniwgiizhig - Henry Flocken IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Frank Guldbrandsen, Adviser May, 2013 © Giniwgiizhig - Henry Flocken 2013 i Acknowledgements My wife, Clarice Mountain, endured the weight of my absence. Her strength helps me succeed. I love her immensely. My children, Terry, Tashina, Samara, Bobbi, Ricky, Ryan, Lisa, Ashley, and Desi, also felt my absence. Marcy Ardito instilled in me that I was smart and could do anything. Dr. Frank Guldbrandsen is a friend and an intellectual guerrilla emancipating cattle from slaughter. ii Dedication This work is dedicated to the late Albert Churchill, a spiritual leader, and his great family. Albert kept traditional ceremonies alive and always shared knowledge with those who asked. Knowledge is useless unless it is shared. He said if we do not share our knowledge, then the flow of new knowledge will be blocked and we will not learn. He always said, “Together we can do anything.” iii Abstract Little is known about traditional Ojibwe civil chief leadership. This critical ethnography is an analysis of traditional Ojibwe civil chief leadership. Hereditary chiefs are interviewed. Chief leadership lies nested in the Anishinaabe Constitution. It is clan-based and value-based. It includes all of creation. Leadership is emergent and symbolic. Chiefs symbolized and are spokespersons for the will of the people. They were selected based on their virtues. The real power is in the people, in clans in council. -

Midewiwin Society Birch Bark Rattle Midewiwin Society Copenhagen

Paying it Forward – free for non-commercial use: www.brucebarryart.com Midewiwin Society • What is it? 1 • Traditionally, the Grand Medicine Society was an esoteric group, including shamans, prophets, and seers, as well as others who successfully undertook the initiation process. The society was thus both a centre of spiritual knowledge and, likely, a source of social prestige. Midewiwin Society • NOT secret society – a discreet group Birch Bark Rattle • History • Was response to Colonization. • Current Status Society? Still Active Copenhagen Chew Lids• Rattle (note snuff can lids)? • 1822: George Weyman begins producing Copenhagen Snuff in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. • Jingle Dress: the traditional way — from the lids of Copenhagen snuff cans. • Now you can buy ‘fake’ lids to make jingle dresses QUESTIONS: 1. is the use of snuff can lids Indigenous people ‘appropriating’ another culture? NOTE: All cultures advance by ‘appropriating’ aspects of other cultures. Note ‘Hoop dancing’ – from Southwest / the Pueblo people that are responsible for the popularity and revival of the hoop dance now / World Champion x2 from Alberta / Hoop dance is still one of the most important healing dances in the White Mountain Apache. 2 Original painting (Kehewin Reserve, Alberta. Cree Territory: Sweet Grass Elder funeral) 3 “After you turn to go, do not look Sand hill back. Your love will keep them 4 Crane Tobacco Ties here”. Feathers Grave Spirit Coloured Houses Ribbons Christian Turtle Crosses Shell Sweetgrass Elk Hide Eagle Midewiwin Society Scraper Feather Dream Catcher Birch Bark Rattle (asabikeshiinh) Student Handout Page 5 vocabulary/language Ojibwe Syllabics: ᑫᑭᓄᐅ' ᐊᒪᐎᓐd ᐏᐃgᐘᐊᐢ Standard Roman Orthography: gekinoo’amawind wiigwaas English: learner: student birCh bark; pieCe of birCh bark Practice Area: BACKGROUND: WIIGWAASABAK (Ojibwe language, plural: wiigwaasabakoon) are birch bark scrolls, on which the Ojibwa (Anishinaabe) people of North America wrote complex geometrical patterns and shapes. -

An Examination of How the Anishinaabe Smudging Ceremony Is

An Examination of the Integration Processes of Anishinaabe Smudging Ceremonies in Northeastern Ontario Health Care Facilities by Amy Shawanda A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Indigenous Relations Faculty of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario, Canada ©Amy Shawanda, 2017 THESIS DEFENCE COMMITTEE/COMITÉ DE SOUTENANCE DE THÈSE Laurentian Université/Université Laurentienne Faculty of Graduate Studies/Faculté des études supérieures Title of Thesis Titre de la thèse An Examination of the Integration Processes of Anishinaabe Smudging Ceremonies in Northeastern Ontario Health Care Facilities Name of Candidate Nom du candidat Shawanda, Amy Degree Diplôme Master of Department/Program Date of Defence Département/Programme Indigenous Relations Date de la soutenance July 21, 2017 APPROVED/APPROUVÉ Thesis Examiners/Examinateurs de thèse: Dr. Darrel Manitowabi (Supervisor/Directeur de thèse) Dr. Thom Alcoze (Committee member/Membre du comité) Dr. Kevin Fitzmaurice (Committee member/Membre du comité) Approved for the Faculty of Graduate Studies Dr. Marion Marr Approuvé pour la Faculté des études supérieures (Committee member/Membre du comité) Dr. David Lesbarrères Monsieur David Lesbarrères Dr. Julie Pelletier Dean, Faculty of Graduate Studies (External Examiner/Examinateur externe) Doyen, Faculté des études supérieures ACCESSIBILITY CLAUSE AND PERMISSION TO USE I, Amy Shawanda, hereby grant to Laurentian University and/or its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my thesis, dissertation, or project report in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or for the duration of my copyright ownership. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis, dissertation or project report.