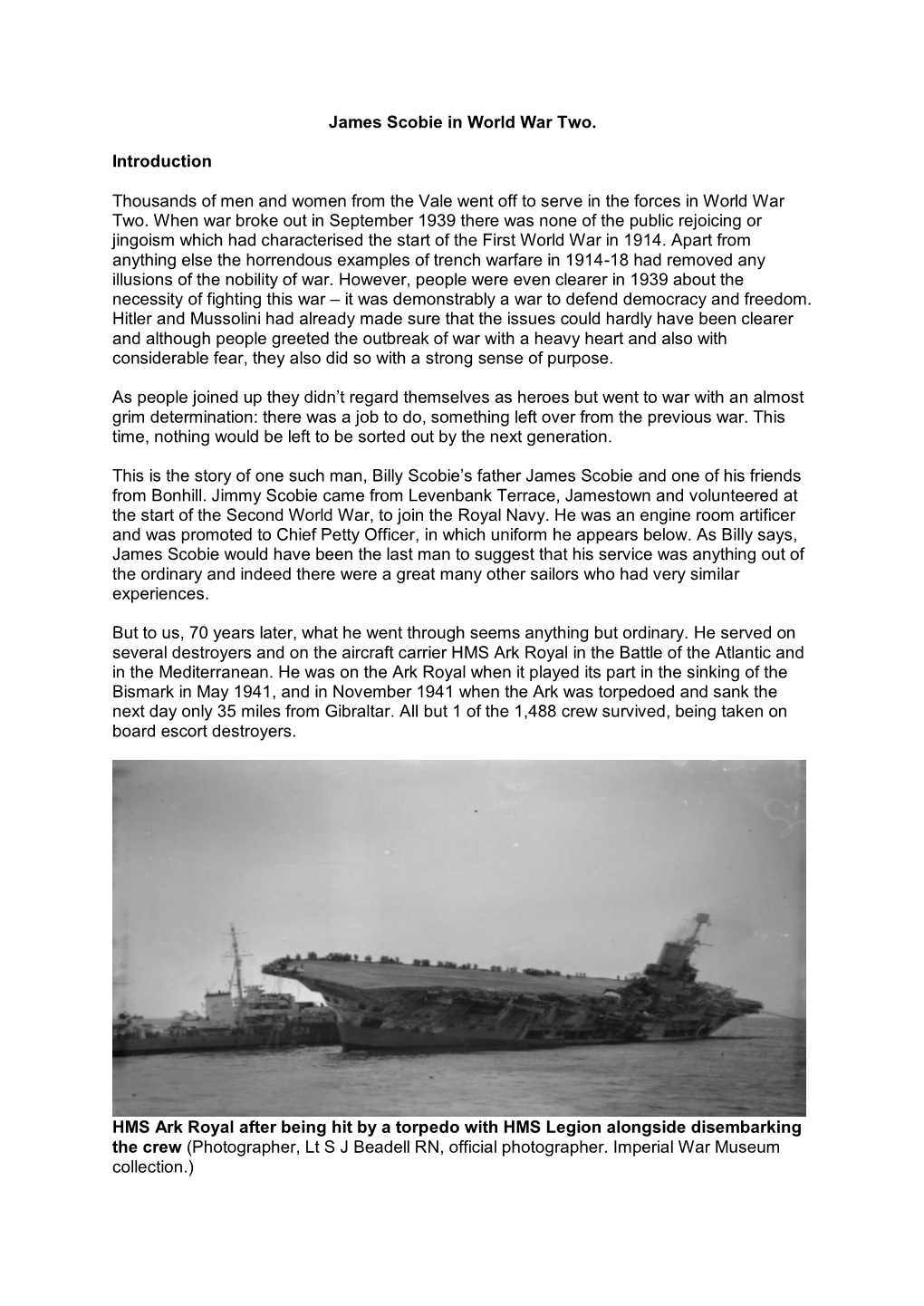

James Scobie in World War Two. Introduction Thousands of Men And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UK National Archives Or (Mainly) 39

Date: 20.04.2017 T N A _____ U.K. NATIONAL ARCHIVES (formerly known as the "PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE") NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES Chancery Lane Ruskin Avenue London WC2A 1LR Kew Tel.(01)405 0741 Richmond Surrey TW9 4DU Tel.(01)876 3444 LIST OF FILES AT THE U.K. NATIONAL ARCHIVES, THE FORMER 'PRO' (PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE) FOR WHICH SOME INFORMATION IS AVAILABLE (IN MOST CASES JUST THE RECORD-TITLE) OR FROM WHICH COPIES WERE ALREADY OBTAINED. FILES LISTED REFER MAINLY TO DOCUMENTS WHICH MIGHT BE USEFUL TO A PERSON INTERESTED IN GERMAN WARSHIPS OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR AND RELATED SUBJECTS. THIS LIST IS NOT EXHAUSTIVE. RECORDS LISTED MAY BE SEEN ONLY AT THE NA, KEW. THERE ARE LEAFLETS (IN THE LOBBY AT KEW) ON MANY OF THE MOST POPULAR SUBJECTS OF STUDY. THESE COULD BE CHECKED ALSO TO SEE WHICH CLASSES OF RECORDS ARE LIKELY TO BE USEFUL. * = Please check the separate enclosure for more information on this record. Checks by 81 done solely with regard for attacks of escort vessels on Uboats. GROUP LIST ADM - ADMIRALTY ADM 1: Admiralty, papers of secretariat, operational records 7: Miscellaneous 41: Hired armed vessels, ships' muster books 51: HM surface ship's logs, till ADM54 inclusive 91: Ships and vessels 92: Signalling 93: Telecommunications & radio 116: Admiralty, papers of secretariat, operational records 136: Ship's books 137: Historical section 138: Ships' Covers Series I (transferred to NMM, Greenwhich) 173: HM submarine logs 177: Navy list, confidential edition 178: Sensitive Admiralty papers (mainly court martials) 179: Portsmouth -

Supplement To

Bumb, 38331 3683 SUPPLEMENT TO Of TUESDAY, the 22nd of JUNE, 1948 by Registered as a newspaper WEDNESDAY, 23 JUNE, 1948 RAID ON MILITARY AND ECONOMIC OBJECTIVES IN THE LOFOTEN ISLANDS. The following Despatch was submitted to the wind or tide. I would stress moreover that Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on the any less time than was allowed for rehearsal ^th April, 1941, by Admiral Sir JOHN C. and planning, and it was two days less than TOVEY, KC.B., D.S.O., Commander-in- originally planned, would have been quite Chief, Home Fleet unacceptable. H.M.S. KING GEORGE V. 3. I would mention the valuable part played t by the submarine SUNFISH in her role as a qth April, 1941. D/F beacon.* This scheme worked well, and OPERATION " CLAYMORE " although in the event the force was able to fix by sights, had this not been possible they Be pleased to lay before Their Lordships the would have been in an uncomfortable position enclosed report of Operation " Claymore "* without the SUNFISH'S aid prepared by the Captain (D), 6th Destroyer Flotilla, H.M S. SOMALI, in command of the 4. iWith reference to paragraph 29 of Captain operation. I concur fully in the report and in D.6's report, I had laid particular emphasis in the remarks of the Rear Admiral (D), Home my verbal instructions on the importance of Fleet, in his Minute II, particularly in punctuality in withdrawing all forces at the paragraph 2. end of the agreed time, and I endorse the opinion that it was necessary to sink the HAM- 2. -

Monitoring of Underwater Archaeological Sites with the Use of 3D Photogrammetry and Legacy Data Case Study: HMS Maori (Malta)

Monitoring of Underwater Archaeological Sites with the use of 3D Photogrammetry and Legacy Data Case study: HMS Maori (Malta) By Djordje Cvetkovic Monitoring of Underwater Archaeological Sites with the use of 3D Photogrammetry and Legacy Data Case study: HMS Maori (Malta) Author: Djordje Cvetkovic Supervisors: Dr Timmy Gambin Dr Kotaro Yamafune Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Global Maritime Archaeology Word Count: 25,499 words Department of Classics and Archaeology University of Malta March, 2020 Abstract A photogrammetric survey has proven to be a reliable method for documenting underwater archaeological sites. Still, the potential which photogrammetry could have in the monitoring of underwater cultural heritage has been just briefly discussed in the past. The purpose of this dissertation is to test if a cost-effective and time-efficient monitoring scheme can be created, for a modern shipwreck site such as HMS Maori, by using photogrammetry and legacy data. The credibility of legacy data (old video footage) was explored, alongside software capable of producing deviation analysis (Cloud Compare). Some of the key findings of this research confirmed that it is possible to geo-reference and extract information from legacy data 3D models by using the method of ‘common points’ (PhotoScan/Metashape). Also, a comparative study confirmed that deviation analysis could generate quantitative data of an underwater archaeological site. This research demonstrated that a reliable monitoring scheme could be constructed with the help of legacy data and deviation analysis. The application of this methodology provided a better understanding of the change that is continuously happening at the shipwreck site of HMS Maori. -

THE ROYAL NAVY and the MEDITERRANEAN VOLUME II: November1940-December 1941 the ROYAL NAVY and the MEDITERRANEAN VOLUME II: November 1940-December1941

WHITEHALL HISTORIES: NAVAL STAFF HISTORIES SeriesEditor: Capt. ChristopherPage ISSN: 1471-0757 THE ROYAL NAVY AND THE MEDITERRANEAN VOLUME II: November1940-December 1941 THE ROYAL NAVY AND THE MEDITERRANEAN VOLUME II: November 1940-December1941 With an Introduction by DAVID BROWN Former Head ofthe Naval Historical Branch, Ministry ofDefence i~ ~~o~~~;n~~~up LONDON AND NEW YORK NAVAL STAFF HISTORIES SeriesEditor: Capt. ChristopherPage ISSN: 1471-0757 Naval Staff Historieswere producedafter the SecondWorld War in orderto provide as full an accountof thevarious actions and operations as was possible at the time. In some casesthe Historieswere basedon earlierBattle Summarieswritten much soonerafter the event,and designedto provide more immediateassessments. The targetaudience for theseNaval Staff Historieswas largely servingofficers; someof the volumeswere originally classified,not to restrict their distribution but to allow the writers to be as candidas possible. The Evacuationfrom Dunkirk: Operation 'Dynamo: 26May-4 June 1940 With a prefaceby W. J. R. Gardner Naval Operationsof the Campaignin Norway, April-June 1940 With a prefaceby ChristopherPage The RoyalNavy and the Mediterranean,Vol. I: September1939-0ctober 1940 With an introductionby David Brown The RoyalNavy and the Mediterranean,Vol. II· November1940-December 1941 With an introductionby David Brown German Capital Shipsand Raidersin World War II: VolumeI: From Gra! Speeto Bismarck,1939-1941 VolumefL· From Scharnhorstto Tirpitz, 1942-1944 With an introductionby Eric Grove The RoyalNavy and the PalestinePatrol With a prefaceby Ninian Stewart During the productionof this Naval Staff History, it was learnedwith greatregret that David Brown, OBE FRHistS,the authorof the new Introductionto this volume, died on 11 August 2001. He had dedicatedhis life to naval history and was Headof the Naval Historical Branchof the Ministry of Defencefor more than a quarterof a century. -

Patrick Joseph Mooney 1910 – 1959 Details of RN Service 1939 -1941

Patrick Joseph Mooney 1910 – 1959 Details of RN Service 1939 -1941 Pembroke I - 19 Sep 39 - 19 Mar 40 Lynx (Brilliant) - 20 Mar 40 - 30 Sep 40 Pembroke - 1 Oct 40 - 8 Dec 40 Pembroke (Legion) - 9 Dec 40 - 10 Mar 41 Pembroke - 11 Mar 41 - 14 Jun 41 Curacoa - 15 Jun 41 - 13 Aug 41 - "R" The “R” is an abbreviation for "RUN” which is the way the RN indicated that someone had deserted. Where the name of a ship appears in brackets it means that it is the ship served in. The name preceding it is that of the accounting base responsible for pay, etc. Some vessels, from the smallest up to destroyers, (which invariably operated in squadrons or flotillas, had insufficient working space on board, i.e. no victualing office, no stores office and only the tiniest ship's office on the larger frigates and destroyers, to look after the Captain's correspondence, daily orders for the ship etc., and didn't have sufficient sleeping and living accommodation to carry the victualling, stores and writer ratings necessary to fill the positions, i.e. these ships were designed purely as fighting machines - and the people who would organize the pay and service documents for the ship's company, victualing accounts and menus and all the various stores that a ship requires to operate, lived ashore in say Pembroke, where they could look after far more people than they could have done had they lived on board, i.e. there was a saving in manpower e.g. 1 Petty Officer Writer and 1 writer could look after the pay documents for 500 officers and ratings - which would be the pay for several ships - depending on the size of the ship's company. -

The Battle for Convoy HG-75, 22-29 October 1941 David Syrett

The Battle for Convoy HG-75, 22-29 October 1941 David Syrett In the autumn of 1941 Nazi Germany was victorious. All of continental Europe, from the Iberian Peninsula to the gates of Moscow, with the exception of Sweden and Switzerland, was under German control. The United States was neutral and Russia, reeling under the impact of German invasion, appeared on the verge of defeat while Britain, aided by its Empire and Commonwealth, fought a desperate battle for existence. Key to the continued survival of Britain was the ability, in the face of attack by German U-boats, to sail convoys of merchant ships to and from the island kingdom. The German navy in the autumn of 1941 had every reason to believe that Britain could be defeated by attacking the island's seaborne supply lines with U-boats. In September of 1941, with about eighty operational U-boats, the Germans sank fifty-three British and Allied merchant ships amounting to 202,820 tons, while in the period from 1 January to 31 September 1941 the British had managed to sink only thirty-one Axis U-boats.' The battle with the U-boats was a conflict the British had to win, for without a constant flow of supplies, transported by merchant ships, Britain would have been forced to surrender, for the civilian population would have starved and all industry would have ground to a halt. Britain's continued survival thus depended on the Royal Navy's ability to escort merchant ships to and from British ports.' To combat U-boat attacks on merchant shipping the British had adopted a strategy of convoys.' These had been employed by the British in the great naval wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as well as in World War I. -

Background – the 'L' Class Destroyers: by 1937, the New Tribal

Background – The ‘L’ class destroyers: By 1937, the new Tribal and ‘J’ class destroyers then under construction were the Royal Navy’s response to the new large destroyers being built in Germany, Japan, and the USA; two more destroyer flotillas were to be ordered for the 1937 program. The first was the ‘K’ class (a repeat of the ‘J’s). For the ‘L’ class, something different was required. The appearance of the French Mogador class with four twin 5.5” guns, ten 21.7” torpedo tubes, and a speed of 39 knots appeared to hopelessly outclass the newest Royal Navy designs. Speeds of all capital ships were going up and destroyers needed a good margin for daylight torpedo attacks; upwards of 40 knots was proposed. A new weatherproof twin 4.7” mount was also being developed in light of experience with the open 4.7” mount then being fitted to the Tribal and ‘J’ classes. Various design studies were pursued, but to carry the new gun mounts at the higher speed would require a much larger ship than the already large Tribal class. It was also felt that the new weatherproof mounting with its maximum elevation of 500 was not sufficient to deal with the increasing threat from the air. A super destroyer was then proposed that could carry three twin 5.25” mounts with a speed of 40 knots. These ships would have been close to 3,000 tons and over 420 feet in length; more of a light cruiser than a destroyer. The commanders of the Home and Mediterranean fleets were in favour of a smaller destroyer as they quite rightly felt that Britain could not afford to engage in the arms race that would result if the super destroyers were to be built. -

The Semaphore Circular No 678 the Beating Heart of the RNA April 2018

The Semaphore Circular No 678 The Beating Heart of the RNA April 2018 The view from RNA Central Office as the ‘Beast from the East’ hits Portsmouth. In the background you can see HMS Queen Elizabeth, testing her evacuation slides (similar to aircraft slides – but with added liferafts! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. Branch and Recruitment and Retention Advisor 2. Veterans Gateway and Preserved Pensions 3. Welfare Seminar 4. Standing Orders Committee Vacancies 5. 2018 Dublin Conference 6. RNVC AB William Savage VC 7. RNBT Assistance with Care Home Fees 8. Charity Donations 9. Finance Corner 10. Naval Recruiting with Ray 11. RNRM Widows’ Association 12. Joke – News Flash 13. National Standard Bearer 2018 14. Joke – Two Brooms 15. RNA Cycling Team 16. Guess Where 17. The RNA Riders Branch 18. Joke – Indian Memory Man 19. RNRMC Twickenham 100 20. Victory Walk 21. Spot the Difference Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of -

Series April May Jun July August September Totals Notes ADM 2022 1934 1015 4971 Includes Ships' Logs AIR 55 143 198 AVIA 29 29 DEFE 465 713 72 1250 Includes UFO Files

Actual Delivery to TNA for period April 2016 to August 2016 Details listed on Individual Series Tabs Series April May Jun July August September Totals Notes ADM 2022 1934 1015 4971 Includes Ships' Logs AIR 55 143 198 AVIA 29 29 DEFE 465 713 72 1250 Includes UFO files. SUPP 1 1 WO 157 157 Total Files 0 0 465 2977 2149 1015 6606 Projected Delivery to TNA for period September 2016 to March 2017 Series October November December January February March Totals Notes The majority of these files will be ADM 53 records (Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy ADM 1143 1000 1000 1000 1000 1000 6143 Department: Ships' Logs) The majority of these files will be AIR 81 records (Air Ministry: Casualty Branch P4(Cas): Enquiries AIR 1614 175 454 1417 1000 4660 into Missing Personnel, 1939-1945 War) DEFE 240 526 908 648 136 96 2554 Various series and files. A large portion of these files will be WO 364 records (War Office: Soldiers' Documents from Pension WO 43 202 1392 559 239 2435 Claims, First World War (Microfilm Copies)) Total Files 3040 1701 2110 3494 3112 2335 15792 Total Files Transferred 3986 Series Piece No File Title ADM 53 199074 HMS Cornwall ADM 53 199075 HMS Cornwall ADM 53 199076 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199077 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199078 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199079 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199080 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199081 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199082 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199083 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199084 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199085 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199086 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199087 HMS Cottesmore ADM 53 199088 HMS Exeter ADM 53 -

{Download PDF} British Aircraft Carriers 1939-45

BRITISH AIRCRAFT CARRIERS 1939-45 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Angus Konstam,Tony Bryan | 48 pages | 20 Jul 2010 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781849080798 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom List of aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy - Wikipedia Other books in this series. Add to basket. Tanks in the Battle of the Bulge Steven J. British Battleships 2 : Vol. German E-boats Gordon Williamson. Technicals Leigh Neville. Japanese Tanks Steven Zaloga. Armored Trains Steven Zaloga. Review quote "This excellent survey of the craft's capabilities is a must for any in-depth military, aircraft or World War II collection! One that will be pulled from the shelves time after time and one I can highly recommend to you. About Angus Konstam Angus Konstam is an acclaimed military and naval historian, and one of Osprey's most experienced and respected authors, with over 35 titles in print. These Osprey titles include British Battlecruisers , British Motor Torpedo Boats , and the forthcoming two-volume study; British Battleships , all of which form part of the New Vanguard list. He has also written over two dozen larger books for other publishers. A former naval officer, underwater archaeologist and maritime museum curator, Angus has a long and passionate love affair with the sea, maritime history and warships. He makes regular television and radio appearances, and has held events at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. Angus is now a full-time writer and historian, as well as being a board member of the Society of Authors, and Publishing Scotland. He currently lives in Edinburgh. For more details visit the author's website at www. -

CLAN CAMPBELL, PAMPAS and TALABOT (Norwegian) Left Alexandria, 16

fcumb. 4371 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the i6th of SEPTEMBER, 1947 by Registered as a newspaper THURSDAY, 18 SEPTEMBER, 1947 THE BATTLE OF SIRTE OF 22ND MARCH, available forces to fight the convoy through, 1942. and to reinforce this escort at dawn D.3 by The following Despatch was submitted to the Force K* from Malta. The route was chosen Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on the with a view to:— 2nd June, 1942, by Admiral Sir Henry H. (a) arriving at Malta at dawn, Harwood, K.C.B., O.B.E., Commander-in- (b) being as far to the westward by dark- Chief, Mediterranean Station. ness on D.2 as was possible consistent with remaining within range of long-range fighter protection during daylight, Mediterranean, (c) taking advantage of a suspected weak- 2nd June, 1942. ness in the enemy's air reconnaissance of the Be pleased to lay before Their Lordships the area between Crete and Cyrenaica, and at the attached reports of proceedings during Opera- same time avoiding suspected U-boat areas, tion M.G. One between igth March and 28th (d) keeping well south during the passage March, 1942.* This operation was carried out of the central basin to increase -the distance with the object of passing a convoy (M.W.io) to be covered by surface forces attempting to of four ships to Malta, where it was most intercept. urgently required. In the course of the opera- tion a greatly superior Italian surface force 4. To reduce the scale of air attack on the which attempted to intercept the convoy was convoy, the Eighth Army were to carry out a driven off. -

Sea History Index Issues 1-168

SEA HISTORY INDEX ISSUES 1-168 Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations Numbers 1st World Congress on Maritime Heritage, 165:46 9/11 terrorist attacks, 99:2, 99:12–13, 99:34, 102:6, 103:5 “30 Years after the Exxon Valdez Disaster: The Coast Guard’s Environmental Protection Mission,” 167:18–20 “The 38th Voyagers: Sailing a 19th-Century Whaler in the 21st Century,” 148:34–35 40+ Fishing Boat Association, 100:42 “100 Years of Shipping through the Isthmus of Panama,” 148:12–16 “100th Anniversary to Be Observed Aboard Delta Queen,” 53:36 “103 and Still Steaming!” 20:15 “1934: A New Deal for Artists,” 128:22–25 “1987 Mystic International,” 46:26–28 “1992—Year of the Ship,” 60:9 A A. B. Johnson (four-masted schooner), 12:14 A. D. Huff (Canadian freighter), 26:3 A. F. Coats, 38:47 A. J. Fuller (American Downeaster), 71:12, 72:22, 81:42, 82:6, 155:21 A. J. McAllister (tugboat), 25:28 A. J. Meerwald (fishing/oyster schooner), 70:39, 70:39, 76:36, 77:41, 92:12, 92:13, 92:14 A. S. Parker (schooner), 77:28–29, 77:29–30 A. Sewall & Co., 145:4 A. T. Gifford (schooner), 123:19–20 “…A Very Pleasant Place to Build a Towne On,” 37:47 Aalund, Suzy (artist), 21:38 Aase, Sigurd, 157:23 Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987, 39:7, 41:4, 42:4, 46:44, 51:6–7, 52:8–9, 56:34–35, 68:14, 68:16, 69:4, 82:38, 153:18 Abbass, D.