Arxiv:2007.06219V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 23 Aug 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Insurance Zagreb

Health Insurance for LES Embassy of the United States of America Zagreb, Croatia Combined Synopsis and Solicitation 19GE5021R0013 Questions and Answers Q1: Please provide five years of loss data(table 1) by year of account including annual net premium (for the same period), incurred claims and membership history. For membership history (Table 2) please provide the number of Employees with single coverage and with family coverage at the end of each year. Please do not include any confidential information, just the overall statistics for the group. Claims information is critical to our pricing and the relationship of claims to employee growth or shrinkage is part of the claims analysis. Table 1 Contractual year Total claims Retention Total Net gain Net gain paid (local amount premium (local USD or EUR currency) (local paid to currency) currency) Insurer (local currency) dd/mm/2016 – dd/mm/2017 dd/mm/2017 – dd/mm/2018 dd/mm/2018 – dd/mm/2019 dd/mm/2019 – dd/mm/2020 dd/mm/2020 – dd/mm/2021 Table 2 Contractual year Single Self plus ONE Family plans dd/mm/2016 – dd/mm/2017 dd/mm/2017 – dd/mm/2018 dd/mm/2018 – dd/mm/2019 dd/mm/2019 – dd/mm/2020 dd/mm/2020 – dd/mm/2021 A1: This is a first-time post is contracting this service, historical data is not available. Q2 : We would like to know if you have been informed of Catastrophic cases, such as: Hemodynamics, Open Heart Surgery, Orthopedic Mayor Surgeries, Organ Transplant, Traumatic Accident, Cancer and Oncology Cases (Radio and Chemotherapy), and hospitalizations with more than 10 days A2: The U.S. -

English No. ICC-01/04-01/06 A7 A8 Date: 18 July 2019 the APPEALS CHAMBER Before

ICC-01/04-01/06-3466-Red 18-07-2019 1/137 NM A7 A8 Statute Original: English No. ICC-01/04-01/06 A7 A8 Date: 18 July 2019 THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Piotr Hofmański, Presiding Judge Chile Eboe-Osuji Judge Howard Morrison Judge Luz del Carmen Ibáñez Carranza Judge Solomy Balungi Bossa SITUATION IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO IN THE CASE OF THE PROSECUTOR v. THOMAS LUBANGA DYILO Public redacted Judgment on the appeals against Trial Chamber II’s ‘Decision Setting the Size of the Reparations Award for which Thomas Lubanga Dyilo is Liable’ No: ICC-01/04-01/06 A7 A8 1/137 ICC-01/04-01/06-3466-Red 18-07-2019 2/137 NM A7 A8 Judgment to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: Legal Representatives of V01 Victims Counsel for the Defence Mr Luc Walleyn Ms Catherine Mabille Mr Franck Mulenda Mr Jean-Marie Biju-Duval Legal Representatives of V02 Victims Trust Fund for Victims Ms Carine Bapita Buyangandu Mr Pieter de Baan Mr Joseph Keta Orwinyo Office of Public Counsel for Victims Ms Paolina Massidda REGISTRY Registrar Mr Peter Lewis No: ICC-01/04-01/06 A7 A8 2/137 ICC-01/04-01/06-3466-Red 18-07-2019 3/137 NM A7 A8 J u d g m e n t ................................................................................................................... 4 I. Key findings ........................................................................................................... 5 II. Introduction to the appeals ..................................................................................... 6 III. Preliminary issues ............................................................................................... 8 A. OPCV’s standing to participate in these appeals ............................................ 8 B. Admissibility of the OPCV’s Consolidated Response to the Appeal Briefs in respect of Mr Lubanga’s Appeal Brief ................................................................... -

Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 – 2030)

Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 – 2030) Republic of Croatia MINISTRY OF THE SEA, TRANSPORT AND INFRASTRUCTURE Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 - 2030) 2nd Draft April 2017 The project is co-financed by the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund. Republic of Croatia Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure I Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 – 2030) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background on development of a Croatian Comprehensive National Transport Plan .................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Transport Development Strategy (TDS 2016) ............................. 4 1.3 Revision of the TDS (2016) Ex-Ante conditionality .................................................. 4 1.4 Methodology for the development of the TDS (2016) ............................................ 5 2 Analysis .................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 General aspects of transport ................................................................................... 7 2.2 Public transport and zero-emission modes ........................................................... 34 2.3 Rail Transport......................................................................................................... 72 2.4 Road transport -

Route Evaluation Report Croatia Eurovelo 8 – Mediterranean Route

Route Evaluation Report Croatia EuroVelo 8 – Mediterranean Route MEDCYCLETOUR Project Davorin Belamarić April 27th 2018 Contents 1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Mission of the project and report objectives ................................................................. 5 1.2 Organization ................................................................................................................ 7 1.3 Brief methodological explanations ................................................................................ 8 1.3.1 Different phases of the route evaluation ................................................................ 8 1.3.2 ECS – European Certification Standard used for this evaluation ........................... 9 1.3.3 Used tools and equipment, photographs ..............................................................10 1.4 Overview of the sections .............................................................................................10 2 Infrastructure ......................................................................................................................16 2.1 Existing route infrastructure ........................................................................................16 2.1.1 Public transport ....................................................................................................19 2.2 Critical deficiencies .....................................................................................................30 -

Croatia National Report 2007

CROATIA NATIONAL REPORT 2007 I Network The total length of motorway network, as completed by the end of 2007 in Croatia, amounts to 1163.5 km. In 2007, 75,9 km of new motorways and 3,8 km of semi motorways were built (as compared to 43 km that were built in 2006), and 15,7 km of existing roads were upgraded to the full motorway profile: On the Motorway A1: Zagreb - Split - Ploče; Dugopolje-Bisko-Šestanovac Sections (37 km) - opened to traffic in full profile in 06/2007 On the Motorway A2: Zagreb - Macelj Krapina-Macelj Section (17.2 km) –13,4 km was completed as full motorway and 3,8 km as semi motorway On the Motorway A5: Beli Manastir-Osijek-border with Bosnia and Herzegovina Sredanci-Đakovo Section (23 km) – opened to traffic as full motorway in 11/2007 On the Motorway A6: Zagreb - Rijeka - on the Vrbovsko-Bosiljevo Section (8,44 km) – upgrade to the full motorway profile of the viaduct Zeceve Drage, tunnel Veliki Gložac, viaduct Osojnik and viaduct Severinske Drage together with corresponding motorway segments in 06/2007 - on the Oštrovica-Kikovica Section (7,25 km) - upgrade to the full motorway profile in 11/2007 On the Motorway A11: Zagreb – Sisak On the Jakuševec-Velika Gorica South Section – completion of the interchange Velika Gorica South and 2,5 km of a motorway segment in 5/2007 and in 09/2007 In Croatia, motorways are operated by 4 companies, i.e. by Hrvatske autoceste d.o.o. (operates all toll motorways except for those in concession) and by three concession companies BINA-ISTRA d.d. -

Supplementary Regulations

SUPPLEMENTARY REGULATIONS INTERNATIONAL RALLY FIA CENTRAL EUROPEAN ZONE RALLY CHAMPIONSHIP INTERNATIONAL ZONE CROATIAN CHAMPIONSHIP CROATIAN NATIONAL RALLY CHAMPIONSHIP MITROPA RALLY CUP BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA NATIONAL RALLY CHAMPIONSHIP BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA RALLY CUP Organizer: Automobile club “Opatija” Co-organizers: 28. R A L L Y OPATIJA 2019 - SUPPLEMENTARY REGULATIONS CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 3. PROGRAMME ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 4. ENTRIES ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 5. INSURENCE ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 6. ADVERTISING AND IDENTIFICATION .......................................................................................................................... 7 7. TRYES ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Croatia National Report 2008

CROATIA NATIONAL REPORT 2008 I Current state of the network At the start of 2009, the total length of the motorway network in Croatia amounted to 1.198,7 km. The following new roadways were opened to traffic in 2008: - 41.5 km of new motorways - 36.9 km of widening of existing road sections to the full motorway profile At the motorway A1: Zagreb-Split - Ploče the Šestanovac – Zagvozd - Ravča sections (40 km) - were opened to traffic in full profile in 12/2008. At the motorway A4: Zagreb - Goričan the section from Goričan to Hungarian border (1,5 km) with the bridge over the Mura River was opened to traffic in 10/2008. At the motorway A6: Zagreb-Rijeka the total of 36,9 km were widened to the full motorway profile (Phase II B) A part of the Oštrovica - Vrata section (12,44 km) – in 09/2008 Vrata - Delnice section (8,93 km) – in 06/2008 Delnice - Kupjak section (7,92 km) – in 06/2008 a part of the Kupjak - Vrbovsko section (7,59 km) – in 06/2008 In Croatia, motorways are operated by 4 companies, i.e. by Hrvatske autoceste d.o.o. (operates all toll motorways except for those in concession) and by three concession companies BINA-ISTRA d.d. Pula (operates the so called Istrian Upsilon - A8 and A9), Autocesta Rijeka-Zagreb d.d. (A6 and A7) and Autocesta Zagreb-Macelj d.o.o. (A2). Number of motorway kilometres - Company 2007. 2008. Tolled facilities total Tolled facilities total 1. HAC d.o.o. 780,0 816,0 2. -

Zagreb Deep Sea Container Terminal Transaction Rijeka, Croatia

Zagreb Deep Sea Container Terminal Transaction Rijeka, Croatia March 2019 Agenda Zagreb Deep Sea Container terminal - unique opportunity State Road D-403 Railway infrastructure Port of Rijeka Development Projects Intermodal yard – Off Dock Terminal 2 20 March 2019 - Zagreb Deep Sea Container Terminal Zagreb Deep Sea Container Terminal Terminal specifications allow for handling of more than 400,000 TEU in phase 1, and 800,000 – 1.000,000 TEU in phase 2, depending on TO technology Phase 1+1A: Phase 2: • Opening: 2023 • Opening: Investor responsibility • Quay length: 400 meters • Quay length: additional 280 meters • Depth alongside: CD -20.0 meters • Depth alongside: CD -20.0 meters • Area: 13.6 hectares • Area: additional 3.7 hectares • Ground slots: 1,968 TEU GS • Ground slots: additional 504 TEU GS • Capacity: > 400,000 TEU • Capacity: > 400,000 – 600,000 TEU, • Intermodal Yard (IY) 2.5 hectares depending on TO technology Intermodal Yard Phase 1A Phase 2 Phase 1 3 ZDSCT Transaction Approach A 2-step Transaction Approach ensures competitiveness and commitments in the bidding process and ensures compliancy with PRAs objectives Approach of the 2-step approach to this container terminal PPP transaction: • General process (below) • Transaction process & phases • Planning aligned with critical path (road D403) Transaction Step Transaction Document Intended Readers Project Information Market Consultation Market Parties (10-25) Memorandum (PIM) Request for Expression Qualification of Interest (RfEoI) Candidates (1-15) Request for Proposal Selection -

Općina Za Ugodan Život I Kvalitetno Poslovanje

Prijedlog strateškog razvojnog programa Općine Matulji za razdoblje od 2016. do 2020. za javnu raspravu - Analiza stanja – Dokument 1 Općina za ugodan život i kvalitetno poslovanje NARUČITELJ: OPĆINA MATULJI Općinski načelnik Mario Ćiković IZRAĐIVAČ: EKONOMSKI FAKULTET SVEUČILIŠTE U RIJECI Dr. sc. Danijela Sokolić, voditeljica projekta Dr. sc. Igor Cvečić Hrvoje Katunar Jana Katunar Vinko Zaninović Petra Adelajda Mirković RADNI TIM: OPĆINA MATULJI Mario Ćiković, Općinski načelnik Eni Šebalj, Zamjenica općinskog načelnika Vedran Kinkela, Zamjenik općinskog načelnika Astra Gašparini, Viša savjetnica za gospodarstvo i potporu razvojnim projektima, koordinatorica projekta Biserka Gadžo, Pročelnica Jedinstvenog upravnog odjela Općine Matulji Ronald Puharić, Rukovoditelj odsjeka za komunalni sustav Helena Stanić, Rukovoditeljica odsjeka za proračun i financije Smiljana Veselinović, Referentica za prostorno uređenje Rijeka, 2016. STRATEŠKI RAZVOJNI PROGRAM OPĆINE MATULJI ZA RAZDOBLJE OD 2016. DO 2020. Dokument 1: Analiza stanja u Općini Matulji Sadržaj 1. Uvod ....................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Opći podaci i zadaci Općine ................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Osnivanje Općine ........................................................................................................... 8 2.2. Ustrojstvo, tijela i nadležnosti ....................................................................................... -

Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 – 2030)

Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 – 2030) Republic of Croatia MINISTRY OF THE SEA, TRANSPORT AND INFRASTRUCTURE Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 - 2030) May 2017 The project is co-financed by the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund. Republic of Croatia Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure I Transport Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (2017 – 2030) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background on development of a Croatian Comprehensive National Transport Plan .................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Transport Development Strategy (TDS 2016) ............................. 4 1.3 Revision of the TDS (2016) Ex-Ante conditionality .................................................. 4 1.4 Methodology for the development of the TDS (2016) ............................................ 5 2 Analysis .................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 General aspects of transport ................................................................................... 7 2.2 Public transport and zero-emission modes ........................................................... 34 2.3 Rail Transport......................................................................................................... 72 2.4 Road transport ...................................................................................................... -

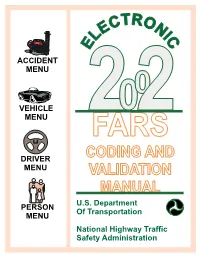

Coding and Validation Manual

TRO EC N L IC E ACCIDENT MENU 2002 VEHICLE MENU FARS CODING AND DRIVER MENU VALIDATION MANUAL U.S. Department PERSON Of Transportation MENU National Highway Traffic Safety Administration ACCIDENT LEVEL VEHICLE LEVEL DRIVER LEVEL PERSON LEVEL APPENDIX LEVEL 2002 MANUAL CHANGES Below is a list of FARS elements that have substantial changes for 2002. These changes, as well as others, are highlighted within the manual by bold/italic type and are marked in the margin with a pointing hand graphic. ELEMENT # ELEMENT NAME NEW/ NEW/ REVISED REVISED COMMENTS VALUES REMARKS A15 Global Positioning X Geo-Locator tool A18 Manner of Collision X X All new codes and remarks A29 Traffic Control Device X New code 41-Electronic Warning Sign A33 Hit-and-Run X X Revised wording of Code 2 New code 4 A39 Related Factors-Accident X X New layout for codes (Example Level Table moved to front of element) New or combined codes Deleted codes V7, V8, V9 Make/Model/Body Type X Updated for 2002 Vehicles Table V16 Vehicle Maneuver X X Code 09 – Controlled Maneuver to Avoid… V21 Vehicle Role X Relating to front-to-front (head- on) collisions V29 Gross Vehicle Weight X Coding of element on power Rating unit only. V34 Related Factors-Vehicle X X New layout for codes (Example Level Table moved to front of element) New or combined codes Deleted codes D12 Driver Height X Revised remarks D13 Driver Weight X Revised remarks D14-18 Driver Level Counters X Previous Recorded Suspensions and Revocations – Can code up to 10 instances without being questioned by Edit Check D22 Related Factors-Driver X X New layout for codes (Example Level Table moved to front of element) New or combined codes Deleted codes P9 Seating Position X X Code 51 should be used for coding passengers in 5th row of 15-seat, 5-row vans. -

Transport and Logistics in Croatia Flanders Investment & Trade Market Survey

TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS IN CROATIA FLANDERS INVESTMENT & TRADE MARKET SURVEY TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS IN CROATIA September 2016 Yazmin Valleyo Sarmiento, Ivan Vandija, Marija Grsetic Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 CROATIA OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Economic Profile ................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Economic Environment Overview ............................................................................................................................................ 11 Croatian Economic Environment SWOT Analysis ......................................................................................................... 12 Croatia SWOT ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 13 CROATIAN TRANSPORT SECTOR ....................................................................................................................................................14 Introduction to the Transport Sector in Croatia .........................................................................................................