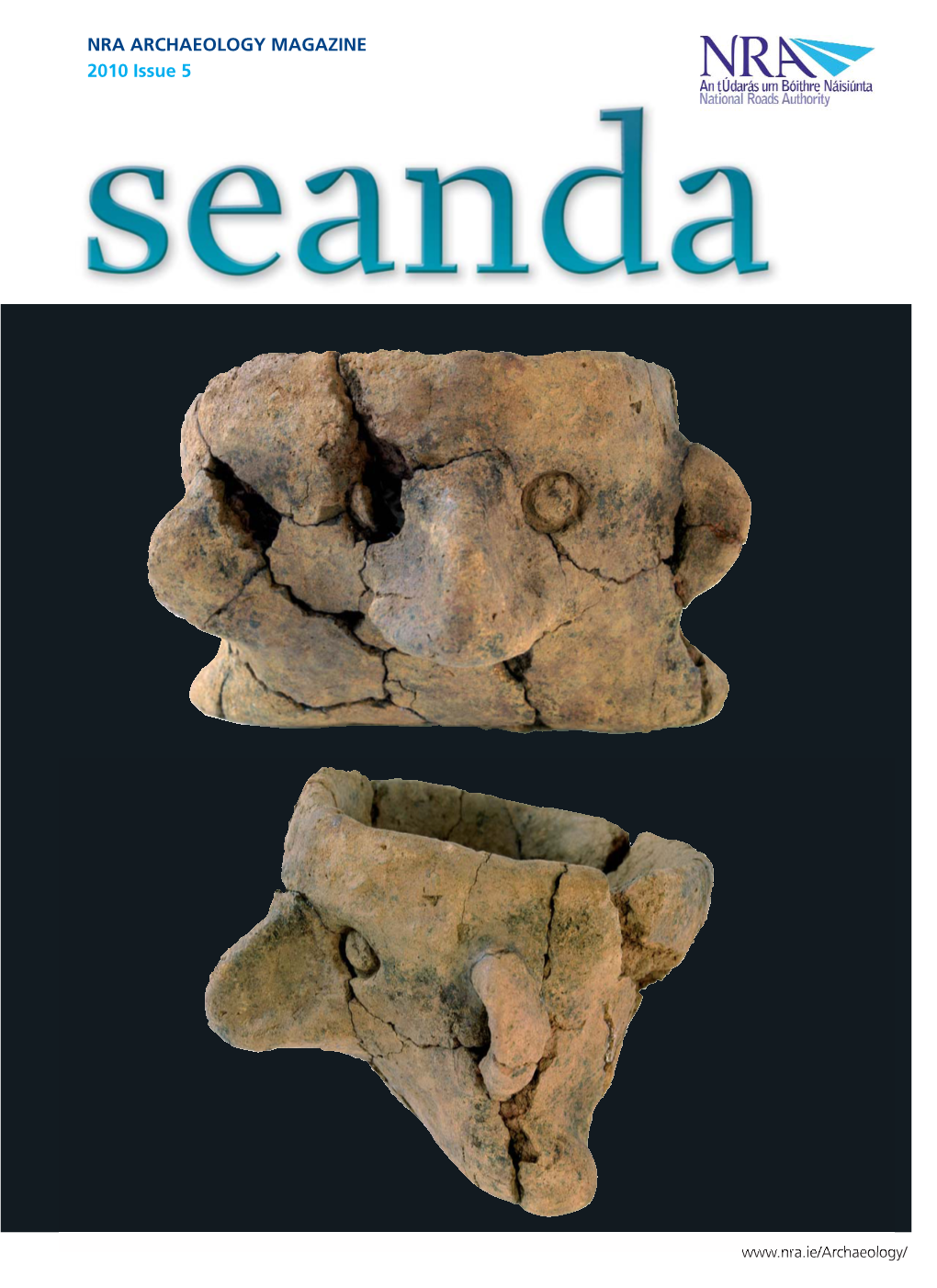

Seadna Cover:Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuarascáil Bhliantúil Annual Report 2014

TUARASCÁIL BHLIANTÚIL ANNUAL REPORT 2014 COMHAIRLE CONTAE LÚ LOUTH COUNTY COUNCIL COUNCIL COAT OF ARMS The Arms of the County, as granted by the Chief Herald to the Council in 1976, are derived as follows:- “Vert a besant charged with a Dexter Hand aversant coupled at the wrist proper” This is the description of the lower part of the shield which is coloured green (vert) and on which is imposed a heraldic expression of the Dextera Dei or Right Hand of God from Muireadach’s Cross at Monasterboice. As on the latter, the armorial design shows the hand against a circular background or nimbus. This section of the Arms represents in particular the rural (or County Health District) part of the County. Chief Sable, two ancient ships, sails set argent The top part of the Arms is black in colour commemorating Muirthemne, the old Irish name of the sea off the County Louth Coast, and which translated into English means the “darkness of the sea”. The ships are inspired by the Coat of Arms of the Borough of Drogheda, which includes a ship anchored at a quayside. Each ship can be taken to represent respectively the Borough of Drogheda and the Urban District of Dundalk, both areas comprised within the administrative County. The ships are also representational of the fact that the County has always been a great centre of trade and commerce. The Crest The Crest incorporates a sword, the symbol of administration, surrounded by ears of barley. This design at once illustrates the nature of the Coat of Arms as a symbol of a civic administration, and the importance of agriculture in the life of the County. -

In the Greater Carlow Town Area Identification of Suitable Sites For

Identification of Suitable Sites for the Location of a Logistics Park in the Greater Carlow Town Area FINAL CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to this Document 1.2 Structure of this Document 2.0 DESCRIPTION 2.1 Definition 2.1.1 Examples of Logistics Parks in Ireland 2.2 Location of Logistics Parks 2.2.1 Strategic Planning Considerations 2.2.2 Local Planning Considerations 2.2.3 Transport Links and Quality 2.2.4 Multi and Inter Modality Potential 3.0 SITE SELECTION 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Methodology 3.3 Site Selection 3.3.1 Step One: Creating Catchments 3.3.2 Step Two: Catchments and Development Exclusion Zones Overlain 3.3.3 Step Three: Application of Constraints Criteria 3.4 Identified Sites 4.0 ASSESSMENT OF IDENTIFIED SITES 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Description of Sites 4.2.1 Site A 4.2.2 Site B 4.3 Selection of a Preferred Site 5.0 CONCLUSION | Study of Possible Sites for the Location of a Logistics Park Proximate to Carlow Town 1 Executive summary This document presents an assessment tool in identifying the most appropriate site for the location of a logistics park in the greater Carlow Town area. It first defines a logistics park and then identifies the locational requirements necessary to accommodate such a use. A Geographical Information System (GIS) is used to identify a series of catchment areas for desirable locational requirements such as roads, rail and services infrastructure. The GIS is also used to determine a series of development exclusion zones around heritage items. -

Frances Lambe Ireland B. 1961 Education Selected Collections

“Oval forms occur in the natural world and are found in cells, pollen grains, seeds, eggs and skulls. These have structures that have evolved to contain matter and provide protection. My hollow sculpted forms explore the theme of containment. Constructed walls form a ‘taut membrane’, which is pierced and made permeable. Intricacy of surface detail is counterbalanced by Duo, 2016 the simplicity of the ovoid form.” Ceramic stoneware, 17 H x 40 W x 27 D cm Frances Lambe Ireland b. 1961 Frances Lambe studied at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. She works with a variety of different clays from terracotta through to white stoneware and porcelain. Frances usually leaves her work unglazed except for the occasional application of oxides. A hallmark of her work is the delicate finish, she pays particular attention to ensure that surface texture unites with form. Her source of inspiration is the natural world, in particular the sea. Her ceramic forms describe an underwater world, the sphere, the oval and undulating forms are recurring themes. Their purity of form recalls stones that have been polished by the movement of water and sand. Frances’ work is in public and private collections including the National Museum of Ireland, the Department of Foreign Affairs of Ireland, the Office of Public Works, and the National Museum of Northern Ireland. Frances Lambe works from her studio in Co. Louth, Ireland. Education 1979 ‐ 83 Diploma in Art Education, National College of Art and Design, Dublin 1983 ‐ 84 Principles of Teaching Art, National -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic. -

External Competitiveness, Internal Cohesion Southern & Eastern

External Competitiveness, Internal Cohesion Southern & Eastern Regional Needs Analysis 2007-13 Brendan Kearney and Associates February 2006 EXTERNAL COMPETITIVENESS, INTERNAL COHESION S& E REGIONAL NEEDS ANALYSIS 2007-13 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 IRELAND’S DRIVING REGION................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NEW INVESTMENT PERIOD 2007-13 ........................................................................................................ 1 1.3 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND REQUIREMENTS............................................................................................. 2 1.4 METHOD, SCOPE AND WORK PROGRAMME ............................................................................................. 3 1.5. WORK PROGRAMME ................................................................................................................................5 1.6 REPORT STRUCTURE................................................................................................................................7 2. REGIONAL PROFILE AND TRENDS.....................................................................................................8 2.1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 AREA AND SPATIAL STRUCTURE -

Biography Anthony Haughey Is an Artist and Lecturer in the Dublin Institute of Technology Where He Supervises Practice-Based Phd’S

Anthony Haughey | Biography Anthony Haughey is an artist and lecturer in the Dublin Institute of Technology where he supervises practice-based PhD’s. He was Senior Research Fellow (2005-8) at the Interface Centre for Research in Art, Technologies and Design in Belfast School of Art, where he completed a PhD in 2009. His artworks and research have been widely exhibited and published nationally and internationally, including, ‘An Act of Hospitality can only be Poetic’, Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda, ‘UNresolved’, video installation, Athens Biennial, ‘The Politics of Images’, Belo Horizonte, Brazil (2017) and ‘Proclamation’ (2016), which toured widely internationally throughout 2016 where he premiered his new video ‘Manifesto’, which was acquired for the permanent collection of The Arts Council / An Chomhairle Ealaíon. Other recent exhibitions include, ‘Uncovering History’, Kunsthaus Graz, ‘Excavation’, Limerick City Gallery, ‘Making History’ and Colombo Art Biennale (2014) as well as a major British Council exhibition ‘Homelands’, touring South Asia. His artworks and scholarly writing has been published in more than eighty publications and his artworks are represented in many important national and international public and private collections. Recent chapter contributions and journal articles include, ‘Imaging the Unimaginable: Returning to the scene of a crime’, Život Umjetnosti art journal, Zagreb, ‘A Landscape of Crisis: Photographing Post Celtic Tiger Ghost Estates’, Canadian Journal of Irish Studies (2017) and ‘Imagining Irish Suburbia’ (Palgrave 2017). He is an editorial advisor for the Routledge journal, ‘Photographies’, a board member of Fire Station Artist Studios, and a member of the Arts Council Acquisitions Committee. He was recipient of Create ‘Arts and Cultural Diversity Award’ (2014) and was lead curator for a major 1916 Commemorative exhibition, ‘Beyond the Pale: The art of revolution’, Highlanes Gallery Drogheda. -

Biography Anthony Haughey Is an Artist, Researcher and a Lecturer in the Dublin Institute of Technology Where He Supervises

Biography Anthony Haughey is an artist, researcher and a lecturer in the Dublin Institute of Technology where he supervises doctoral practice-based projects. He was a Research Fellow (2005-8) at the Interface Centre for Research in Art, Technologies and Design at the University of Ulster Belfast, where he completed a PhD in 2009. His work has been widely exhibited nationally and internationally, most recently Uncovering History, curated by Camera Austria in Kuunsthaus Graz, Excavation, Limerick City Gallery, where he premiered his new film, Unresolved, twenty years after the Srebrenica genocide, Making History, Colombo Art Biennale (2014), Art of the Troubles, Ulster Museum, Belfast (2014), Settlement in Belfast Exposed, Northern Ireland: 30 years of photography in the MAC and Belfast Exposed, New Irish Landscapes, Three Shadows Gallery, Beijing, Homelands, a major British Council exhibition touring South Asia, Citizen in Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda and MCAC, Portadown, Strike!, Labour and Lockout, Upending – an exhibition of enquiries in Limerick City Gallery of Art. He recently completed a commission for the Aftermath project, which toured galleries in Ireland throughout 2014. A publication (out of print) from this commission was launched in January 2015, available at: http://issuu.com/anthonyhaughey/docs/ah_aftermath_issuu His photographs and writings have been published in more than seventy publications (including eight in 2014). Monographs include The Edge of Europe (1996), Disputed Territory (2006) and an artist’s book State (2011). His work is represented in many international public and private collections and he is an editorial advisor for the Routledge journal, Photographies. He has published several chapter contributions including, ‘Dislocations: Participatory Media with Refugees in Ireland and Malta’, in Goodnow, K. -

N9/N10 Kilcullen to Waterford Scheme, Phase 4 – Knocktopher to Powerstown (Figure 1)

N9/N10 KILCULLEN TO WATERFORD SCHEME, PHASE 4 – KNOCKTOPHER TO POWERSTOWN Ministerial Direction A032 Scheme Reference No. Registration No. E3614 Site Name AR074, Ennisnag 1 Townland Ennisnag County Kilkenny Excavation Director Richard Jennings NGR 251417 145689 Chainage 33740 FINAL REPORT ON BEHALF OF KILKENNY COUNTY COUNCIL MARCH 2011 N9/N10 Phase 4: Knocktopher to Powerstown Ennisnag 1, E3614, Final Report PROJECT DETAILS N9/N10 Kilcullen to Waterford Scheme, Project Phase 4 – Knocktopher to Powerstown Ministerial Direction Reference No. A032 Excavation Registration Number E3614 Excavation Director Richard Jennings Senior Archaeologist Tim Coughlan Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd, 120b Greenpark Road, Consultant Bray, Co. Wicklow Client Kilkenny County Council Site Name AR074, Ennisnag 1 Site Type Prehistoric structure Townland(s) Ennisnag Parish Ennisnag County Kilkenny NGR (easting) 251417 NGR (northing) 145689 Chainage 33740 Height OD (m) 62.521 RMP No. N/A Excavation Dates 20–31 August 2007 Project Duration 20 March 2007–18 April 2008 Report Type Final Report Date March 2011 Richard Jennings and Tim Report By Coughlan Jennings, R. and Coughlan, T. 2011 E3614 Ennisnag 1 Final Report. Unpublished Final Report. National Report Reference Monuments Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd i N9/N10 Phase 4: Knocktopher to Powerstown Ennisnag 1, E3614, Final Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This final report has been prepared by Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in compliance with the directions issued to Kilkenny County Council by the Minister for Environment, Heritage and Local Government under Section 14A (2) of the National Monuments Acts 1930–2004 and the terms of the Contract between Kilkenny County Council and Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd. -

8 Infrastructure and Environment

Kilkenny City &Environs Draft Development Plan 8. Infrastructure & Environment 8 Infrastructure and Environment 8.1 Transport The principal transport aim of Kilkenny Borough Council and Kilkenny County Council is to develop an efficient, sustainable and integrated multi-modal transport and communications system facilitating the movement of people, goods and services in the City and Environs. This is essential for the economic and social development of the City, its Environs and the county as a whole. Different types of land uses, by facilitating economic activity, will give rise to demands for travel and transport provision. Equally the provision of transport services will give rise to changes in land uses. In its transport policies and objectives, Kilkenny Borough Council and Kilkenny County Council will seek to reduce the reliance on private motor vehicles and will promote an increased use of public transport, walking and cycling. 8.1.1 Climate Change The Council has had regard to the National Climate Change Strategy (2007-2012) in framing its policies and objectives in this Development Plan and will seek to play its part towards the achievement of the national targets set out in therein. Two principles as espoused in the NSS have been applied to reduce transport-related energy consumption; • The formulation of a settlement strategy which is intended to guide urban and rural settlement patterns and communities to reduce distance from employment, services and leisure facilities and to make use of existing and future investments in public services; including public transport. • Maximising access to, and encouraging use of, public transport, cycling and walking. In addition, the Councils support of renewable technologies and encouragement of more sustainable energy-efficient building methods will further reduce our dependence on non-renewable energy sources. -

Monaghan County Museum Handling Collection

Applying for Loans It is essential to make a booking for all loans from the Handling Collection. At least two to three days notice is required by the Education and Outreach Officer but you are advised to book as early as possible to avoid disappointment. To borrow material, a list of items required should be telephoned or preferably emailed to the Education and Outreach Officer stating the date you wish to collect loans and when they will be returned. Items can be borrowed as themed groups or as individual pieces. Duration of Loans Objects may be borrowed for a period of time up to a maximum of one month. This time may be reduced subject to demand and waiting lists. Collection & Return of Loans Booked loans can be collected from and returned to the Museum between 9.15am and 4.00pm from Monday to Friday or on Saturday by prior agreement. Loans must be returned no later than 4.30 on the last day of the agreed loan period and must be accepted by a member of staff. It is essential to return the items on or before the agreed date to facilitate other bookings. Any borrower who retains material beyond the loan period may not be eligible for future loans. Archaeology 2 Transport 8 Communication 14 handling Household and Agriculture 18 collection Schools and Education 22 Politics and Conflict 24 28 Monaghan County Museum’s Natural History Handling Service was established in 1982, with a small number of items. Folklife 30 A successful application to the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht was made to Towns, Villages and Estates 34 expand this service. -

Kilkenny City & Environs Draft Development Plan Deletions in Strikethrough Proposed Insertions in Italics

Proposed Amendments City & Environs Plan 22nd April 2008 Kilkenny City & Environs Draft Development Plan Where an issue was raised as part of a submission to the Draft Plan the reference number of the corresponding submission has been given e.g. (Dxxx). Deletions in strikethrough Proposed Insertions in italics Chapter 1: Strategic Context Following consideration of the Manager’s Report the following change was agreed: Strategic goals • To provide the highest quality living environments possible to all the citizens of Kilkenny City and Environs members of our community. New Section 1.9 Monitoring and review (D229) The purpose of monitoring and evaluation is to assess the effectiveness or otherwise of policies and objectives in terms of achieving stated aims. Section 15(2) of the Act states that the manager shall, not later than 2 years after the making of a development plan, give a report to the members of the authority on the progress achieved in securing the objectives and section 95(3)(a) of the Act expressly requires that the 2 year report includes a review of progress on the housing strategy. Following adoption of the Plan key information requirements will be identified focusing on those policies and objectives central to the aims and strategy of the plan. These information requirements identified will be evaluated on an annual basis during the plan period. 1 Proposed Amendments City & Environs Plan 22nd April 2008 Chapter 3 Map change – show employment centres Following consideration of the Manager’s Report the following change was agreed: 3.4 Development Strategy As part of the development strategy the major employment areas are shown on the Map 3.1. -

Learning and Access in Museums

Northern Ireland Museums Council Learning and Access in Museums Case Studies from Northern Ireland Bringing together, for the first time, examples of a range of learning projects provided right across the Northern Ireland museums sector. Learning and Access in Museums 01 Case Studies from Northern Ireland Contents 01 Causeway Museum Service 3 Community Outreach Project 02 Derry City Council Heritage and Museum Service 12 Flight of the Earls 2007 Education and Outreach Project 03 Derry City Council Heritage & Museum Service 16 Good Relations Programme at the Tower Museum 04 Down County Museum 20 Downpatrick Young Archaelogists’ 05 Fermanagh County Museum and Cavan County Museum 24 Connecting Peoples, Places & Heritage 06 Irish Linen Centre and Lisburn Museum 27 Education for Employability 07 Mid-Antrim Museums Service 30 Making History Community History Programme 08 National Museums Northern Ireland 38 Coming to Our Senses 09 National Museums Northern Ireland: Ulster Folk & Transport Museum 44 Travelling Times Exhibition 10 National Museums Northern Ireland: Ulster Museum 47 Outreach Art Project 11 National Museums Northern Ireland: Ulster Museum Belfast Parks 51 and Belfast Zoo Rainforest 12 National Museums Northern Ireland: Ulster Museum 54 Sure Start Project 13 National Trust Castle Ward 57 Sort It Out! Conflict Resolution Programme 14 National Trust Florence Court 61 The Wedding Breakfast, Community Relations Programme 15 Naughton Gallery at Queen’s University 64 Community Alphabets Project 16 Naughton Gallery at Queen’s University