External Competitiveness, Internal Cohesion Southern & Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CMATS Public Consultation

Bonneagar Iompair Eireann Transport Infrastructure Ireland CORK METROPOLITAN AREA DRAFT TRANSPORT STRATEGY 2040 - PUBLIC CONSULTATION DOCUMENT LRT Cork City Council Black Ash Park & Ride Comhairle Cathairle Chaorcaí PUBLIC CONSULTATION We would like to know you views on the draft Cork Metropolitan Area Transport Strategy and any items of interest or concern. All comments will be considered and will inform the finalisation of the Cork Metropolitan Area Transport Strategy. The public consultation will run from 15th May - 28th June 2019. Full details of the draft Cork Metropolitan Submissions Public Information Events Area Transport Strategy can be found at Submissions are welcomed from the public Public Information Events will be held the following link: up until 5pm, Friday 28th June 2019, send between 3pm - 8pm at the following www.nationaltransport.ie/public- your submission online, by email or post. locations on the following dates: consultations/current • Wednesday 5th June Website: Imperial Hotel, Cork City Consultation material will be available www.nationaltransport.ie/public- to view at Cork City Hall and Cork consultations/current • Thursday 6th June County Hall for the duration of the Oriel House Hotel, Ballincollig consultation period. Email: • Wednesday 12th June [email protected] The complete set of CMATS background Radisson Hotel, Little Island reports area as follows: Post: • Thursday 13th June • Baseline Conditions Report; Cork Metropolitian Area Transport Strategy, Carrigaline Court Hotel, Carrigaline • Planning Datasheet Development Report; National Transport Authority, • Wednesday 19th June • Demand Analysis Report; Dún Scéine, Blarney Castle Hotel, Blarney. • Transport Modelling Report; Harcourt Lane, • Transport Options Development Report; Dublin 2, D02 WT20. • Supporting Measures Report; • Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA); and • Appropriate Assessment (AA). -

In the Greater Carlow Town Area Identification of Suitable Sites For

Identification of Suitable Sites for the Location of a Logistics Park in the Greater Carlow Town Area FINAL CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to this Document 1.2 Structure of this Document 2.0 DESCRIPTION 2.1 Definition 2.1.1 Examples of Logistics Parks in Ireland 2.2 Location of Logistics Parks 2.2.1 Strategic Planning Considerations 2.2.2 Local Planning Considerations 2.2.3 Transport Links and Quality 2.2.4 Multi and Inter Modality Potential 3.0 SITE SELECTION 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Methodology 3.3 Site Selection 3.3.1 Step One: Creating Catchments 3.3.2 Step Two: Catchments and Development Exclusion Zones Overlain 3.3.3 Step Three: Application of Constraints Criteria 3.4 Identified Sites 4.0 ASSESSMENT OF IDENTIFIED SITES 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Description of Sites 4.2.1 Site A 4.2.2 Site B 4.3 Selection of a Preferred Site 5.0 CONCLUSION | Study of Possible Sites for the Location of a Logistics Park Proximate to Carlow Town 1 Executive summary This document presents an assessment tool in identifying the most appropriate site for the location of a logistics park in the greater Carlow Town area. It first defines a logistics park and then identifies the locational requirements necessary to accommodate such a use. A Geographical Information System (GIS) is used to identify a series of catchment areas for desirable locational requirements such as roads, rail and services infrastructure. The GIS is also used to determine a series of development exclusion zones around heritage items. -

Spotlight on Cork

SPOTLIGHT ON CORK WELCOME TO CORK, IRELAND Cork is a proud city of approximately 150,000 people that sits on the River Lee and at the head of Cork Harbour, the second biggest natural harbor in the world. It is a city of renowned learning with a world-class university and many specialist colleges. It is home to a thriving business economy that includes giants in the pharmaceutical and technology industries. With more than 24 festivals, a rich music and arts history, and successful professional sports teams, Cork was recently named the European Capital of Culture. Contents Climate and Geography 02 Cost of Living and Transportation 03 Visa, Passport, Language, and Currency Information 04 Lifestyle, Sports, and Attractions 05 Culture, Shopping, and Dining 06 Schools and Education 07 GLOBAL MOBILITY SOLUTIONS l SPOTLIGHT ON CORK l 01 SPOTLIGHT ON CORK Cork Climate Graph 100oF 10 in. CLIMATE 80oF 8 in. The climate of Cork, like the rest of Ireland, is mild oceanic and changeable with abundant rainfall and a lack of temperature extremes. Temperatures 60oF 6 in. below 32°F (0°C) or above 77°F (25 °C) are rare. 40oF 4 in. Cork has an average of roughly 48 inches (1,228 mm) of precipitation annually, most of which is 20oF 2 in. rain. The low altitude of the city, and moderating influences of the harbor, mean that lying snow very rarely occurs in the city itself. Cork is also a JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC generally foggy city, with an average of 97 days High Temp Low Temp Precipitation of fog a year, most common during mornings and during winter. -

Final Combined Amendment No. 2 Midleton LAP.Pdf

Cork County Council Amendment No2 to Midleton Electoral Area Local Area Plan 2011 (Carrigtwohill North Framework Masterplan and Water‐Rock Framework Masterplan) Prepared by Cork County Council Planning Policy Unit November 2015 Amendment No2 Midleton Electoral Area Local Area Plan 2011, Section 3: Settlements and Other Locations Main Settlement: Carrigtwohill the commuter rail link, with the additional growth occurring mainly line runs to the north. The town lies on an undulating plain with the after 2014. The population growth targets are predicated on the hills rising steeply to the north of the rail line providing a backdrop to delivery of the masterplan for the lands north of the rail line as the town. The town has developed in a linear fashion with the N25 1 Carrigtwohill originally identified in the 2005 SLAP. CASP Update also highlights taking an alignment to the south and largely providing the town’s the need for additional focus on the provision of hard and soft southern boundary. Encouraged by the Cork Land Use & infrastructure, including self-sustaining retail and service functions. Transportation Studies of 1978 and 1992, the IDA Business park has 1.1 VISION AND CONTEXT been developed as a large area of modern, technology based, 1.1.5. As well as functioning as a main town, Carrigtwohill is industrial development at the western end of the town and a designated as a Strategic Employment Centre in the 2009 County significant landbank of industrial land also demarcates the eastern Development Plan, as one of the primary locations for large scale The overall aims for Carrigtwohill are to realise the significant extent of the town. -

Cork Conference Bid Document Template

Sample - Cork Conference Bid Document – “Conference Name” – Cork, Ireland, 3-7 October 2010 1 | 54 – Contents Executive Summary 3 Invitation Letters of Invitation and Endorsement 7 Introduction 9 Conference Topic 10 Welcome to Cork Welcome to Cork 14 What Cork Offers 16 International Conferences held in Cork 17 Cork Access 18 Why Ireland? Welcome to Ireland 23 The Conference Conference Dates 27 Venues & Facilities 28 Conference Organising Committee 31 Conference Schedule 34 Social Events 36 Benefits of Ireland hosting the Conference 37 Cork Accommodation & Venues 38 Budget and Event Promotion Budget 42 Available Support 44 Preliminary Budget 46 Marketing & Promotion 47 Visitor Information Pre and post-event tours 50 Testimonials 52 Visitor Information on Cork and Ireland 53 2 | 54 – Executive Summary Ireland and Cork in particular, is recognised internationally and regarded as a very popular destination, with superb conference facilities, unparalleled hospitality and scenic beauty. This reputation leads in general to increased conference attendance for both delegates and accompanying persons. Observing the trend of increased delegate numbers, Cork is equipped to handle increased delegate numbers based on forward projections. Cork, located on Ireland's south coast, is the Republic of Ireland's second largest city and capital of the province of Munster. Ireland ideally located on the edge of Europe, is less than an hour from London, less than two hours from Paris or Brussels and just six hours from the east coast of the US by air. Cork Airport is just 10 minutes drive from Cork City. The Airport has flights to & from 40 scheduled destinations in Ireland, the UK and continental Europe, with up to ten flights a day to Dublin, 12 flights to London, and daily departures for Amsterdam, Paris, Prague, Munich, Rome, Malaga, Belfast, Birmingham, and Manchester with connecting flights to other European and American destinations. -

N9/N10 Kilcullen to Waterford Scheme, Phase 4 – Knocktopher to Powerstown (Figure 1)

N9/N10 KILCULLEN TO WATERFORD SCHEME, PHASE 4 – KNOCKTOPHER TO POWERSTOWN Ministerial Direction A032 Scheme Reference No. Registration No. E3614 Site Name AR074, Ennisnag 1 Townland Ennisnag County Kilkenny Excavation Director Richard Jennings NGR 251417 145689 Chainage 33740 FINAL REPORT ON BEHALF OF KILKENNY COUNTY COUNCIL MARCH 2011 N9/N10 Phase 4: Knocktopher to Powerstown Ennisnag 1, E3614, Final Report PROJECT DETAILS N9/N10 Kilcullen to Waterford Scheme, Project Phase 4 – Knocktopher to Powerstown Ministerial Direction Reference No. A032 Excavation Registration Number E3614 Excavation Director Richard Jennings Senior Archaeologist Tim Coughlan Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd, 120b Greenpark Road, Consultant Bray, Co. Wicklow Client Kilkenny County Council Site Name AR074, Ennisnag 1 Site Type Prehistoric structure Townland(s) Ennisnag Parish Ennisnag County Kilkenny NGR (easting) 251417 NGR (northing) 145689 Chainage 33740 Height OD (m) 62.521 RMP No. N/A Excavation Dates 20–31 August 2007 Project Duration 20 March 2007–18 April 2008 Report Type Final Report Date March 2011 Richard Jennings and Tim Report By Coughlan Jennings, R. and Coughlan, T. 2011 E3614 Ennisnag 1 Final Report. Unpublished Final Report. National Report Reference Monuments Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd i N9/N10 Phase 4: Knocktopher to Powerstown Ennisnag 1, E3614, Final Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This final report has been prepared by Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd in compliance with the directions issued to Kilkenny County Council by the Minister for Environment, Heritage and Local Government under Section 14A (2) of the National Monuments Acts 1930–2004 and the terms of the Contract between Kilkenny County Council and Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd. -

8 Infrastructure and Environment

Kilkenny City &Environs Draft Development Plan 8. Infrastructure & Environment 8 Infrastructure and Environment 8.1 Transport The principal transport aim of Kilkenny Borough Council and Kilkenny County Council is to develop an efficient, sustainable and integrated multi-modal transport and communications system facilitating the movement of people, goods and services in the City and Environs. This is essential for the economic and social development of the City, its Environs and the county as a whole. Different types of land uses, by facilitating economic activity, will give rise to demands for travel and transport provision. Equally the provision of transport services will give rise to changes in land uses. In its transport policies and objectives, Kilkenny Borough Council and Kilkenny County Council will seek to reduce the reliance on private motor vehicles and will promote an increased use of public transport, walking and cycling. 8.1.1 Climate Change The Council has had regard to the National Climate Change Strategy (2007-2012) in framing its policies and objectives in this Development Plan and will seek to play its part towards the achievement of the national targets set out in therein. Two principles as espoused in the NSS have been applied to reduce transport-related energy consumption; • The formulation of a settlement strategy which is intended to guide urban and rural settlement patterns and communities to reduce distance from employment, services and leisure facilities and to make use of existing and future investments in public services; including public transport. • Maximising access to, and encouraging use of, public transport, cycling and walking. In addition, the Councils support of renewable technologies and encouragement of more sustainable energy-efficient building methods will further reduce our dependence on non-renewable energy sources. -

Kilkenny City & Environs Draft Development Plan Deletions in Strikethrough Proposed Insertions in Italics

Proposed Amendments City & Environs Plan 22nd April 2008 Kilkenny City & Environs Draft Development Plan Where an issue was raised as part of a submission to the Draft Plan the reference number of the corresponding submission has been given e.g. (Dxxx). Deletions in strikethrough Proposed Insertions in italics Chapter 1: Strategic Context Following consideration of the Manager’s Report the following change was agreed: Strategic goals • To provide the highest quality living environments possible to all the citizens of Kilkenny City and Environs members of our community. New Section 1.9 Monitoring and review (D229) The purpose of monitoring and evaluation is to assess the effectiveness or otherwise of policies and objectives in terms of achieving stated aims. Section 15(2) of the Act states that the manager shall, not later than 2 years after the making of a development plan, give a report to the members of the authority on the progress achieved in securing the objectives and section 95(3)(a) of the Act expressly requires that the 2 year report includes a review of progress on the housing strategy. Following adoption of the Plan key information requirements will be identified focusing on those policies and objectives central to the aims and strategy of the plan. These information requirements identified will be evaluated on an annual basis during the plan period. 1 Proposed Amendments City & Environs Plan 22nd April 2008 Chapter 3 Map change – show employment centres Following consideration of the Manager’s Report the following change was agreed: 3.4 Development Strategy As part of the development strategy the major employment areas are shown on the Map 3.1. -

Acomprehensivemobilit Yplanforcountykilkenn Y

A COMPREHENSIVE MOBILITY PLAN FOR COUNTY KILKENNY A Comprehensive Mobility Plan for County Kilkenny “If our lives are dominated by a search for happiness, then perhaps few activities reveal as much about the dynamics of this quest – in all its ardour and paradoxes – than our travels.” The Art of Travel, Alain de Botton alternatively… “Transport, motorways and tramlines starting and then stopping taking off and landing the emptiest of feelings Disappointed People…” Let Down, Radiohead 1 A Comprehensive Mobility Plan for County Kilkenny This plan was commissioned by Kilkenny LEADER Partnership CLG on behalf of a number of stakeholders comprising the Kilkenny Integrated Transport Action Group. The plan was authored by Ian Dempsey, Prescience, between January and May 2018. Prescience wishes to acknowledge the contribution of many organisations and individuals who gave willingly of their time, information, perspective and ambition. www.prescience.eu This project was part funded by Kilkenny LEADER Partnership through the European Agriculture Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural areas” 2 A Comprehensive Mobility Plan for County Kilkenny Table of Contents Chapter Page 1. Executive Summary 4 2. Defining the Scope of a Mobility Plan 6 3. Context and Rationale 11 4. A Socio-economic profile of Kilkenny 38 5. Transport Infrastructure & Metrics in Kilkenny 55 6. Travel Dynamics, Mode and Metrics 71 7. Provision of and Access to Key Services 83 8. Public Realm and Streetscape 97 9. Transit Design, Integration & Connectivity 102 10. Licensed Public Transport Provision 113 11. Deprivation, Disadvantage and Access to Transport 133 12. Recommendations 149 Appendices 164 3 A Comprehensive Mobility Plan for County Kilkenny 1. -

ZD2/RZD2012.Pdf, .PDF Format 1063KB

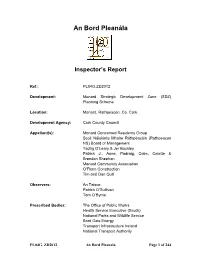

An Bord Pleanála Inspector’s Report Ref.: PL04G.ZD2012 Development: Monard Strategic Development Zone (SDZ) Planning Scheme Location: Monard, Rathpeacon, Co. Cork. Development Agency: Cork County Council Appellant(s): Monard Concerned Residents Group Scoil Náisiúnta Mhuire Ráthpéacáin (Rathpeacon NS) Board of Management Tadhg O’Leary & Jer Buckley Patrick J., Anne, Padraig, Colm, Colette & Brendan Sheehan Monard Community Association O’Flynn Construction Tim and Dan Quill Observers: An Taisce Patrick O’Sullivan Tom O’Byrne Prescribed Bodies: The Office of Public Works Health Service Executive (South) National Parks and Wildlife Service Bord Gais Energy Transport Infrastructure Ireland National Transport Authority PL04G. ZD2012 An Bord Pleanala Page 1 of 244 INSPECTOR: Robert Speer Date of Site Inspection: 20th November, 2015 Date of Oral Hearing: 24th - 27th November, 2015, 2nd December, 2015 & 14th January, 2016 PL04G. ZD2012 An Bord Pleanala Page 2 of 244 Contents: 1.0 Introduction 2.0 The Monard Strategic Development Zone 3.0 Site Location and Description 4.0 Relevant Planning History 5.0 The Planning Scheme 6.0 Appeals 7.0 Observations 8.0 Response to Grounds of Appeal 9.0 Policy Context 10.0 Oral Hearing 11.0 Assessment 12.0 Conclusions and Recommendation PL04G. ZD2012 An Bord Pleanala Page 3 of 244 1.0 INTRODUCTION: 1.1 This report relates to 7 No. appeals lodged under Section 169 of the Planning and Development Act, 2000, as amended, against the adoption of the Planning Scheme for the Monard Strategic Development Zone pursuant to the provisions of Section 169(4)(b) of the Act. In this respect it should be noted that although a Draft Planning Scheme for the Monard Strategic Development Zone was published by the Development Agency in April, 2015, on the basis that Cork County Council decided by resolution on 27th July, 2015 not to make a formal decision on the Draft Planning Scheme under the provisions of Section 169(4) of the Act, the Scheme was deemed to have been made on 11th August, 2015 by way of a legislative ‘default mechanism’. -

Carrigtwohill SLAP 2005.Pdf

Carrigtwohill Special Local Area Plan This Special Local Area Plan has been prepared in accordance with the Planning and Development Act 2000 (as amended). It is one of three Special Local Area Plans prepared to guide development at important locations along the Blarney – Midleton rail corridor. Local Area Plans were also prepared for each of the 10 Electoral Areas in County Cork. It should also be noted that where indicative diagrams are included in the plan these are for illustrative purposes only and the map entitled ‘Zoning Map’ is the official legal map. Schedule Issue Date Containing No. 1 September, 2005 Adopted Carrigtwohill Special Local Area Plan April, 2006 Amendment 1: Ballyadam Copyright © Cork County Council 2006 – all rights reserved Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2004/07CCMA/Cork County Council Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright © Ordnance Survey Ireland, 2006 Printed on 100% Recycled Paper Carrigtwohill Special Local Area Plan, September, 2005 Carrigtwohill Special Local Area Plan, September, 2005 FOREWORD Note From The Mayor Note From The Manager The adoption of these Special Local Area Plans is a significant milestone in the joint efforts of the The framework established by the Cork Area Strategic Plan, County Development Plan 2003, and the County Council and Iarnród Éireann to secure the establishment of a suburban rail network for Cork. Feasibility Study commissioned by Iarnród Éireann guides these Special Local Area Plans. They form They also follow an extensive process of public consultation with a broad range of interested a critical part of our sustainable rail network for Cork because they ensure that future population will be individuals, groups and organisations who put forward their views and ideas on the future development focused in the hinterland of the new rail stations of this area and how future challenges should be tackled. -

28 – 29 MAIN STREET, Midleton, Co

28 – 29 MAIN STREET, Midleton, Co. Cork For Sale By Private Treaty Location The property occupies a central location on the east side of Main Street, between its junctions with Oliver Plunkett Place and Connolly Street. The property also enjoys vehicular access to the rear via Drury’s Avenue. This is a central location with a good volume of passing traffic, both pedestrian and vehicular. On-street parking is available to both sides of Main Street and adjacent occupiers include Boots and Vodafone. The Property N.B. For identification purposes only. Not to scale. Transport Midleton is adjacent to the N25 which links Cork City with Rosslare Europort. The town’s railway station is on the Cork Suburban Rail network and is one of two termini (the other being Cobh) into and out of Cork Kent railway station. Bus Eireann also run a number of routes serving the town with destinations to include Ballycotton, Whitegate, Cork City, Waterford, Ballinacurra and Carrigtwohill. Description 28-29 Main Street comprises a three storey mid-terrace building with additional dormer space at roof level. The original building appears to be of traditional masonry construction with plastered elevations and a pitched slate covered roof incorporating six dormer windows. A single storey extension has been added to the rear of the ground floor which appears to be of concrete block construction with plastered elevations and flat asphalt covered roof. Internally the property provides a ground floor retail unit with suspended ceilings. All upper floors are in office accommodation. Total floor areas extend to approximately 377 Sq.