Epilogue the Aftermath and the Romanticization of the Liang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Third Series • Volume Xxiii Part 1 • Third Series Third

part 1 volume xxiii • academia sinica • taiwan • 2010 INSTITUTE OF HISTORY AND PHILOLOGY third series asia major • third series • volume xxiii • part 1 • 2010 xiao tong’s preface to tao yuanming ji ping wang Between Reluctant Revelation and Disinterested Disclosure: Reading Xiao Tong’s Preface to Tao Yuanming ji iao Tong 蕭統 (501–531), posthumously the Crown Prince of Re- X .splendent Brilliance (Zhaoming taizi 昭明太子) of the Liang dynasty (502–557), is most famous for his compilation of the Wen xuan 文選, one of the most important anthologies in the Chinese literary tradi- tion.1 Yet the Liang prince made another contribution to the world of letters, namely, his fervent praise of Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 (365–427) that serves as a crucial link in the reception history of one of the great- est poets in China. The prince’s promotion of Tao Yuanming is seen in three interrelated activities: rewriting Tao Yuanming’s biography, collecting Tao’s works, and composing for the collection a long pref- ace (referred to here as the Preface). While the biography has proved a useful point of comparison for studying the canonization history of Tao Yuanming as a poet,2 the Preface attracts scholarly attention for a I would like to thank David R. Knechtges, Paul W. Kroll, Martin Kern, Susan Naquin, Ben- jamin Elman, Willard Peterson, and Paul R. Goldin, who read and commented on this paper. Their feedback has benefited me greatly in the process of revision. I also owe thanks to the editors and anomymous readers at Asia Major for comments and suggestions. -

Xiao Gang (503-551): His Life and Literature

Xiao Gang (503-551): His Life and Literature by Qingzhen Deng B.A., Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute, China, 1990 M.A., Kobe City University of Foreign Languages, Japan, 1996 Ph.D., Nara Women's University, Japan, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2013 © Qingzhen Deng, 2013 ii Abstract This dissertation focuses on an emperor-poet, Xiao Gang (503-551, r. 550-551), who lived during a period called the Six Dynasties in China. He was born a prince during the Liang Dynasty, became Crown Prince upon his older brother's death, and eventually succeeded to the crown after the Liang court had come under the control of a rebel named Hou Jing (d. 552). He was murdered by Hou before long and was posthumously given the title of "Emperor of Jianwen (Jianwen Di)" by his younger brother Xiao Yi (508-554). Xiao's writing of amorous poetry was blamed for the fall of the Liang Dynasty by Confucian scholars, and adverse criticism of his so-called "decadent" Palace Style Poetry has continued for centuries. By analyzing Xiao Gang within his own historical context, I am able to develop a more refined analysis of Xiao, who was a poet, a filial son, a caring brother, a sympathetic governor, and a literatus with broad and profound learning in history, religion and various literary genres. Fewer than half of Xiao's extant poems, not to mention his voluminous other writings and many of those that have been lost, can be characterized as "erotic" or "flowery". -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Preface of Selections of Refined Literature”

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 416 4th International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2020) Exploration on the Completion Time of the “Preface of Selections of Refined Literature” Yong Yu The College of Literature and Journalism Sichuan University Chengdu, China Abstract—The opinions on the completion time of the At the end of the "Preface of Selections of Refined "Preface of Selections of Refined Literature" have always been Literature", it describes the beginning year and end year of divergent and inconsistent. To examine its completion time, it the works collected in "Selections of Refined Literature" and is necessary to combine various internal and external factors the total number of volumes, and explains the basis of the such as the preface, the compilation style of "Selections of style order arrangement. Especially, the poems are Refined Literature", the life story of the editor, and the process subdivided into subtypes and sequenced according to the of writing the book. It helps to make clear the long-standing times. Obviously, it is neither possible for the editor to related disputes in the researches on "anthologizing presume the total number of volumes compiled before principles". completion of "Selections of Refined Literature" nor possible Keywords: “Preface of Selections of Refined Literature”, to previously have an idea of subdividing poems into Xiao Tong, completion time subtypes. If the "Preface of Selections of Refined Literature" was written in the compilation process but before completion I. INTRODUCTION of "Selections of Refined Literature", the editor would also not available to conclude that the total number of volumes is When was the "Preface of Selections of Refined thirty. -

A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments

2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE 2011) Wuhan, China 10 - 12 May 2011 Pages 1 - 867 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1129C-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-5088-6 1/7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALGORITHMS, MODELS, SOFTWARE AND TOOLS IN BIOINFORMATICS: A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments ............................................................1 Hongbin Lee, Bo Wang, Xiaoming Wu, Yonggang Liu, Wei Gao, Huili Li, Xu Wang, Feng He A New Promoter Recognition Method Based On Features Optimal Selection.................................................................5 Lan Tao, Huakui Chen, Yanmeng Xu, Zexuan Zhu A Center Closeness Algorithm For The Analyses Of Gene Expression Data ...................................................................9 Huakun Wang, Lixin Feng, Zhou Ying, Zhang Xu, Zhenzhen Wang A Novel Method For Lysine Acetylation Sites Prediction ................................................................................................ 11 Yongchun Gao, Wei Chen Weighted Maximum Margin Criterion Method: Application To Proteomic Peptide Profile ....................................... 15 Xiao Li Yang, Qiong He, Si Ya Yang, Li Liu Ectopic Expression Of Tim-3 Induces Tumor-Specific Antitumor Immunity................................................................ 19 Osama A. O. Elhag, Xiaojing Hu, Weiying Zhang, Li Xiong, Yongze Yuan, Lingfeng Deng, Deli Liu, Yingle Liu, Hui Geng Small-World Network Properties Of Protein Complexes: Node Centrality And Community Structure -

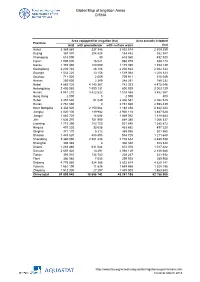

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

(Shijing): on “Filling out the Missing Odes” by Shu Xi

Righting, Riting, and Rewriting the Book of Odes (Shijing): On “Filling out the Missing Odes” by Shu Xi Thomas J. MAZANEC University of California, Santa Barbara1 A series of derivative verses from the late-third century has pride of place in one of the foundational collections of Chinese poetry. These verses, “Filling out the Missing Odes” by Shu Xi, can be found at the beginning of the lyric-poetry (shi 詩) section of the Wenxuan. This essay seeks to understand why such blatantly imitative pieces may have been held in such high regard. It examines how Shu Xi’s poems function in relation to the Book of Odes, especially their use of quotation, allusion, and other intertextual strategies. Rather than imitate, borrow, or forge, the “Missing Odes” seek to bring the idealized world of the Odes into reality by reconstructing canonical rites with cosmic implications. In so doing, they represent one person’s attempt to stabilize the chaotic political center of the Western Jin in the last decade of the third century. The “Missing Odes” reveal that writing, rewriting, ritualizing, and anthologizing are at the heart of early medieval Chinese ideas of cultural legitimation. Introduction If one were to open the Wenxuan 文選, the foundational sixth-century anthology compiled by Crown Prince Xiao Tong 蕭統 (501–531), and turn to the section on shi- poetry 詩 in hopes of understanding early medieval lyricism, the first pages would present one with a curious series of six poems, different in style and tone from the more famous works that follow. This set of tetrametric verses by Shu Xi 束皙 (ca. -

Sun Tzu the Art Of

SUN TZU’S BILINGUAL CHINESE AND ENGLISH TEXT Art of war_part1.indd i 28/4/16 1:33 pm To my brother Captain Valentine Giles, R. C., in the hope that a work 2400 years old may yet contain lessons worth consideration to the soldier of today, this translation is affectionately dedicated SUN TZU BILINGUAL CHINESE AND ENGLISH TEXT With a new foreword by John Minford Translated by Lionel Giles TUTTLE Publishing Tokyo Rutland, Vermont Singapore ABOUT TUTTLE “Books to Span the East and West” Our core mission at Tuttle Publishing is to create books which bring people together one page at a time. Tuttle was founded in 1832 in the small New England town of Rutland, Vermont (USA). Our fundamental values remain as strong today as they were then—to publish best-in-class books informing the English-speaking world about the countries and peoples of Asia. The world has become a smaller place today and Asia’s economic, cultural and political infl uence has expanded, yet the need for meaning- ful dialogue and information about this diverse region has never been greater. Since 1948, Tuttle has been a leader in publishing books on the cultures, arts, cuisines, lan- guages and literatures of Asia. Our authors and photographers have won numerous awards and Tuttle has published thousands of books on subjects ranging from martial arts to paper crafts. We welcome you to explore the wealth of information available on Asia at www.tuttlepublishing.com. Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Distributed by Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. North America, Latin America & Europe www.tuttlepublishing.com Tuttle Publishing 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon Copyright © 2008 Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York *SUBJECT to GENERAL and SPECIFIC NOTES to THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 *SUBJECT TO GENERAL AND SPECIFIC NOTES TO THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY OF AMENDED SCHEDULES An asterisk (*) found in schedules herein indicates a change from the Debtor's original Schedules of Assets and Liabilities filed December 30, 2005. Any such change will also be indicated in the "Amended" column of the summary schedules with an "X". Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, C, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor's assets. Add the amounts from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor's liabilities. AMOUNTS SCHEDULED NAME OF SCHEDULE ATTACHED NO. OF SHEETS ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER YES / NO A - REAL PROPERTY NO 0 $0 B - PERSONAL PROPERTY YES 30 $6,002,376,477 C - PROPERTY CLAIMED AS EXEMPT NO 0 D - CREDITORS HOLDING SECURED CLAIMS YES 2 $79,537,542 E - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED YES 2 $0 PRIORITY CLAIMS F - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED NON- YES 356 $5,366,962,476 PRIORITY CLAIMS G - EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED YES 2 LEASES H - CODEBTORS YES 1 I - CURRENT INCOME OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) J - CURRENT EXPENDITURES OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) Total number of sheets of all Schedules 393 Total Assets > $6,002,376,477 $5,446,500,018 Total Liabilities > UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 GENERAL NOTES PERTAINING TO SCHEDULES AND STATEMENTS FOR ALL DEBTORS On October 17, 2005 (the “Petition Date”), Refco Inc. -

Study on the Rise and Fall of the Duyi Fu and Geography Record of the Pre-Tang Dynasty and the Mutual Influence

2017 International Conference on Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities (SSAH 2017) Study on the Rise and Fall of the Duyi Fu and Geography Record of the Pre-Tang Dynasty and The Mutual Influence Tongen Li College of Chinese Language and Literature of Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, Gansu, 730070 Keywords: The Duyi Fu, The Geography Record, The Earthly Consciousness, The Literariness, The Mutual Influence Abstract. There are two important regional works in the Tang Dynasty. As an important subject of Fu literature, it has a close relationship with the flourishing period of the Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties. Both have a common origin, but also has a different development track; both self-contained, but also mutual influence. The artistic nature of the city and the nature of the material are permeated with each other, and the development and new changes are promoted. Introduction Duyi Fu, including Jingdu Fu and Yi Ju Fu, began in the Western Han Dynasty, to Yang Xiong "Shu Du Fu" as the earliest. Xiao Tong "anthology" received more than 90 articles, divided into 15 categories, the first category of "Kyoto", income 8; Li Fang and others compiled "Wen Yuan Yinghua" sub-43, "Kyoto" Yi "in the head; Chen Yuan-long series of" calendar Fu "column" city "head, a total of 10 volumes of 70 articles. Duyi Fu mainly revolves around the geography, politics, culture and social life of the metropolis,used for singing praises of the emperor and boast of their homelands, with obvious geographical characteristics. Geography Record also known as the geography, geography or geography book, "Sui Shu · books catalogue" called it "geography". -

Risen from Chaos: the Development of Modern Education in China, 1905-1948

The London School of Economics and Political Science Risen from Chaos: the development of modern education in China, 1905-1948 Pei Gao A thesis submitted to the Department of Economic History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, March 2015 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 72182 words. I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Eve Richard. Abstract My PhD thesis studies the rise of modern education in China and its underlying driving forces from the turn of the 20th century. It is motivated by one sweeping educational movement in Chinese history: the traditional Confucius teaching came to an abrupt end, and was replaced by a modern and national education model at the turn of the 20th century. This thesis provides the first systematic quantitative studies that examine the rise of education through the initial stage of its development.