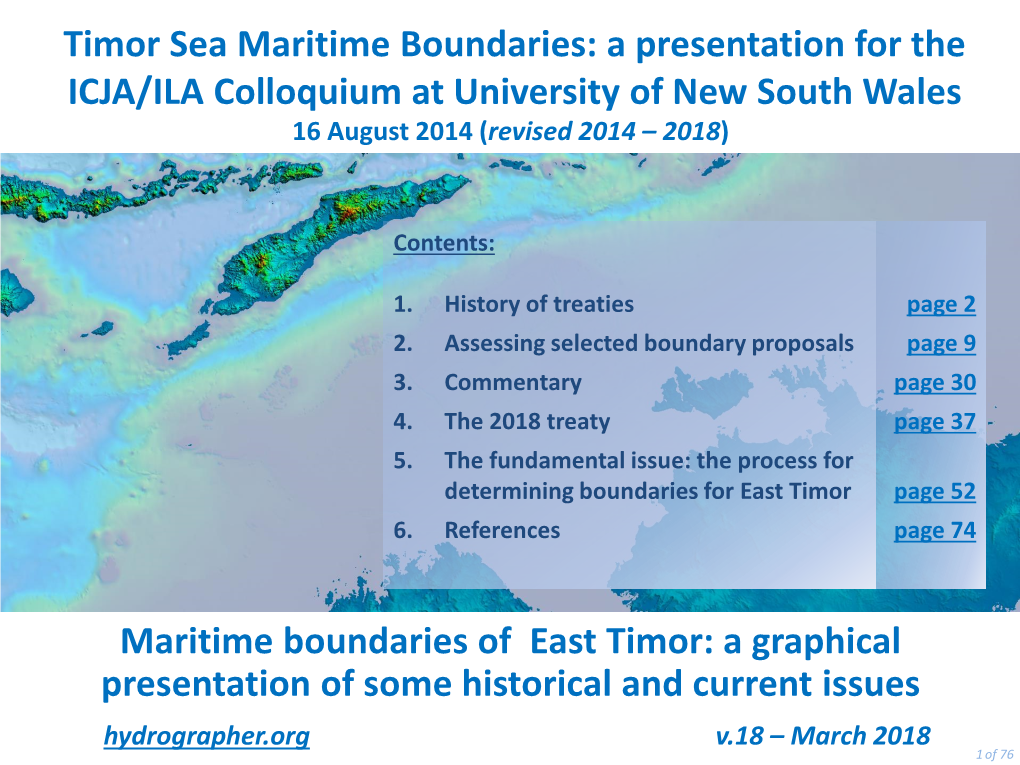

Colloquium at University of New South Wales 16 August 2014 (Revised 2014 – 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Development and Economic Transition Under International Governance: the Case of East Timor

Revised August 22 2000 National development and economic transition under international governance: the case of East Timor Jorge Braga de Macedo Institute of Tropical Research and Nova University at Lisbon José Braz TEcFinance Ltd, Lisbon Rui Sousa Monteiro Nova University at Lisbon Introduction East Timor evolved as a nation over several centuries, with a strong spiritual identity making up for colonial neglect. The occupation by neighboring Indonesia also contributed to solidify the national identity of East Timor. In their intervention over the past year, international agencies have been slow in recognizing that this is an asset for the democratic governance of the new state that is unique in post-conflict situations. Ignoring this initial condition of national development can have adverse consequences for the choice of an economic transition path. In the current international governance setup, military intervention may already have been excessive relative to the empowerment of the CNRT (National Council for Timorese Resistance). The consequence was a waste of time and financial resources. The fact that East Timor already existed as a nation obviates the need for the manifestations of economic nationalism usually present in recently constituted nation- states. In their strategy for national development, democratically elected authorities can avoid the temptation to create an autonomous currency, to nationalize significant economic sectors or to implement other protectionist measures. Such a national development strategy has direct implications on fiscal policy. Without a need to finance heavy government intervention in economic life, tax design can be guided by principles of simplicity and have relatively low rates. Rather than relying on a complex progressive personal and corporate tax collection system, the royalties from oil and gas exploration can then perform the distributive functions. -

![GEOGRAPHY)] Born with the Vision of “Enabling a Person Located at the Most Remote Destination a Chance at Cracking AIR 1 in IAS”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8566/geography-born-with-the-vision-of-enabling-a-person-located-at-the-most-remote-destination-a-chance-at-cracking-air-1-in-ias-1088566.webp)

GEOGRAPHY)] Born with the Vision of “Enabling a Person Located at the Most Remote Destination a Chance at Cracking AIR 1 in IAS”

IASBABA.COM 2018 IASBABA [IASBABA’S 60 DAYS PLAN-COMPILATION (GEOGRAPHY)] Born with the vision of “Enabling a person located at the most remote destination a chance at cracking AIR 1 in IAS”. IASbaba’s 60 Days Plan – (Geography Compilation) 2018 Q.1) Consider the following. 1. Himalayas 2. Peninsular Plateau 3. North Indian Plains Arrange the following in chronological order of their formations. a) 1-3-2 b) 2-1-3 c) 2-3-1 d) 3-2-1 Q.1) Solution (b) The oldest landmass, (the Peninsula part), was a part of the Gondwana land. The Gondwana land included India, Australia, South Africa, South America and Antarctica as one single land mass. The northward drift of Peninsular India resulted in the collision of the plate with the much larger Eurasian Plate. Due to this collision, the sedimentary rocks which were accumulated in the geosyncline known as the Tethys were folded to form the mountain system of western Asia and Himalayas. The Himalayan uplift out of the Tethys Sea and subsidence of the northern flank of the peninsular plateau resulted in the formation of a large basin. In due course of time this depression, gradually got filled with deposition of sediments by the rivers flowing from the mountains in the north and the peninsular plateau in the south. A flat land of extensive alluvial deposits led to the formation of the northern plains of India. Do you know? Geologically, the Peninsular Plateau constitutes one of the ancient landmasses on the earth’s surface. It was supposed to be one of the most stable land blocks. -

Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in Figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011

37 Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 FAO WATER Irrigation in Southern REPORTS and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 37 Edited by Karen FRENKEN FAO Land and Water Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2012 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107282-0 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

Thesis Is Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia

LEADERSHIP AT THE PRIMARY SCHOOL LEVEL IN POST-CONFLICT TIMOR-LESTE: A STUDY OF THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, RECENT DEVELOPMENTS AND CURRENT CONCERNS OF SCHOOL LEADERS Shayla Maria Babo Ribeiro Master of Business Administration Master of Management Bachelor of Science (Cartography) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia Graduate School of Education Faculty of Arts, Business, Law and Education 2019 THESIS DECLARATION I, Shayla Maria Babo Ribeiro, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by The University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval #: RA/4/1/7396. Written patient consent was obtained and archived for the research involving patient data reported in this thesis. -

Download Article (PDF)

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 170 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL. SURVEY.... OF -INDIA Geographical distribution .and Zoogeography of Odonata (Insecta). of Meghalaya, India TRIDIB RANJAN MITRA ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 170 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Geographical distribution and Zoogeography of Odonata (Illsecta) of Meghalaya, India TRIDIB RANJAN MITRA Zoological Sitrvey of India, Calcutta Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of Indirz, Calcutta Zoological Survey of India Calcutta 1999 Published: March. 1999 ISBN· 81-85874-11- 5 © Goverllnlent of India, 1999 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in a retrieval system or translnitted, in any form or by any means, ele~tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold hired out or otherwise disposed of wit~out the publisher's consent, in any form of bindi~g or cover other than that in which.it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price i ndicaled by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable PRICE: Rs. 100/· S 6 £4 Published at the Publication Division ~y the Director, Zoological Survey of India, 234/4 AJC Bose Road, 2nd MSO Building (13th Floor), Nizaln Palace, Calcutta-700 020 after laser typesetting by Krishna Printing Works, 106 Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-700 006 and printed by Hooghly Printing Co. Ltd. -

Mountains of Asia a Regional Inventory

International Centre for Integrated Asia Pacific Mountain Mountain Development Network Mountains of Asia A Regional Inventory Harka Gurung Copyright © 1999 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development All rights reserved ISBN: 92 9115 936 0 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226 Kathmandu, Nepal Photo Credits Snow in Kabul - Madhukar Rana (top) Transport by mule, Solukhumbu, Nepal - Hilary Lucas (right) Taoist monastry, Sichuan, China - Author (bottom) Banaue terraces, The Philippines - Author (left) The Everest panorama - Hilary Lucas (across cover) All map legends are as per Figure 1 and as below. Mountain Range Mountain Peak River Lake Layout by Sushil Man Joshi Typesetting at ICIMOD Publications' Unit The views and interpretations in this paper are those of the author(s). They are not attributable to the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and do not imply the expression of any opinion concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Preface ountains have impressed and fascinated men by their majesty and mystery. They also constitute the frontier of human occupancy as the home of ethnic minorities. Of all the Mcontinents, it is Asia that has a profusion of stupendous mountain ranges – including their hill extensions. It would be an immense task to grasp and synthesise such a vast physiographic personality. Thus, what this monograph has attempted to produce is a mere prolegomena towards providing an overview of the regional setting along with physical, cultural, and economic aspects. The text is supplemented with regional maps and photographs produced by the author, and with additional photographs contributed by different individuals working in these regions. -

Geography of World and India

MPPSCADDA 1 GEOGRAPHY OF WORLD AND INDIA CONTENT WORLD GEOGRAPHY ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ INDIAN GEOGRAPHY ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ 2 MPPSCADDA 3 GEOGRAPHY WORLD 1. UNIVERSE INTRODUCTION TO GEOGRAPHY • The word ‘Geography’ is a combination of two Greek words "geo" means Earth and "graphy" means write about. • Geography as a subject not only deals with the features and patterns of surface of Earth, it also tries to scientifically explain the inter-relationship between man and nature. • In the second century, Greek scholar Eratosthenes (Father of Geography) adopted the term 'Geography'. BRANCHES OF GEOGRAPHY Physical Geography Human Geography Bio - Geography Cultural Geography Climatology Economic Geography Geomorphology Historical Geography Glaciology Political Geography Oceanography Population Geography Biogeography Social Geography Pedology Settlement Geography PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY It deals with the physical environment and various processes that bring about changes in the physical environment on the Earth's surface. It includes: 1. Bio-Geography: The study of the geographic distribution of organisms. 2. Climatology: The study of climate or weather conditions averaged over a period of time. 3. Geomorphology or Physiographic: The scientific study of landforms and processes that shape them. 4. Glaciology: The study of glaciers and ice sheets. 5. Oceanography: The study of all aspects of the ocean including temperature, ocean current, salinity, fauna and flora, etc. 6. Pedology: The study of various types of Soils. 4 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY Human geography deals with the perspective of human and its functions as well as its interaction with the environment. It studies people, communities and cultures with an emphasis on relations of land across space. It includes: 1. Cultural Geography: The study of the spatial variations among cultural groups and spatial functioning of the society. -

Maritime Boundaries of East Timor: a Graphical Presentation of Some Historical and Current Issues Hydrographer.Org V.16A –May 2016 1 of 57 Up

Timor Sea Maritime Boundaries: a presentation for the ICJA/ILA Colloquium at University of New South Wales 16 August 2014 Contents: 1. History of Treaties page 2 2. Assessing selected boundary proposals page 9 3. Commentary page 26 4. The fundamental issue: the process for determining boundaries for East Timor page 33 5. References page 55 Maritime boundaries of East Timor: a graphical presentation of some historical and current issues hydrographer.org v.16a –May 2016 1 of 57 Up 1. History of Treaties 2. Assessing selected boundary proposals 3. Commentary 4. The fundamental issue: the process for determining boundaries for East Timor 5. References hydrographer.org 2 of 57 Agreement between Australia and Indonesia establishing Certain Seabed Boundaries in the Area of the Timor and Arafura Seas 1972 (entry into force 1973) Boundaries between the area of seabed that is adjacent to and appertains to the Commonwealth of Australia and the area of seabed that is adjacent to and appertains to the Republic of Indonesia. The boundary is interrupted in the “Timor Gap”. The dashed yellow line is the published Indonesian baseline. The dashed red line is the Australian baseline. 3 of 57 Treaty between Australia and Indonesia on the Zone of Cooperation in an Area between the Indonesian Province of East Timor and Northern Australia [Timor Gap Treaty] 1989 (entry into force 1991) The treaty establishes in the “Timor Gap” a zone of cooperation with 3 areas: Area A (central area, with equal sharing of the benefits of exploitation of petroleum resources); Area B (southern area, Australia paying Indonesia 10% of gross Resource Rent Tax); Area C (northern area, Indonesia paying Australia 10% of Contractor’ Income Tax). -

Cultivating Plantations and Subjects in East Timor: a Genealogy

bki Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 169 (2013) 326-361 brill.com/bki Cultivating Plantations and Subjects in East Timor: A Genealogy Christopher J. Shepherd and Andrew McWilliam1 Australian National University [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract This article traces the emergence and institutionalization of plantation systems and cash crops in East Timor over two centuries. It examines the continuities, ruptures and shifting politics across successive plantation styles and political regimes, from Portuguese colonial- ism through Indonesian occupation to post-colonial independence. In following plantation agriculture from its origins to the present, the article explores how plantation subjects have been formed successively through racial discourse, repressive discipline, technical authority and neoliberal market policies. We argue that plantation politics have been instrumental in reproducing the class distinctions that remain evident in East Timor today. Keywords East Timor, plantations, history, governmentality we should try to grasp subjection in its material instance as a constitution of subjects. (Foucault 1980: 97) Introduction In 2008, civil society organizations in East Timor got wind of secret deal- ings between the Timorese government and an Indonesian company con- cerning plans to establish a number of large sugar-cane plantations on East Timor’s south coast. A controversy between civil society and government quickly erupted. Over the ensuing months, arguments around employment 1 For the first-named -

The Meeting of the Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka (BBINS) Malaria Drug Resistance Monitoring Network

In the Asia-Pacific region, the monitoring of the efficacy of antimalarial drugs including artemisinins and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) has become a routine activity of the national malaria programs using a standardized WHO therapeutic efficacy study (TES) protocol. It aims to identify early signs of resistance of recommended treatment regimens to drive evidence-based review and update of a country's national drug policy. The 4th Meeting of the BBINS Malaria Drug Resistance Monitoring Network (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka) convened in New Delhi, India on 15–16 October 2019. The discussions highlighted the results of therapeutic efficacy studies including updates on molecular markers for drug resistance, showing that the 1st-line artemisinin-based combinations therapies (ACT) in all countries are currently effective against both P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria; countries to further strengthen The Meeting of the Bangladesh, Bhutan, malaria microscopy QA; and adopt iDES for monitoring of malaria drug efficacy in areas with low malaria cases as part of the programme's elimination surveillance activities. India, Nepal, Sri Lanka (BBINS) Also discussed were workplans for continuing studies over the next two years. Malaria Drug Resistance Monitoring Network A Report New Delhi, India, 15–16 October 2019 SEA-MAL-283 SEA-MAL-283 The Meeting of the Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka (BBINS) Malaria Drug Resistance Monitoring Network A Report New Delhi, India, 15–16 October 2019 The Meeting of the Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka (BBINS) Malaria Drug Resistance Monitoring Network SEA-MAL-283 © World Health Organization 2020 Some rights reserved. -

Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in Figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011

37 Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 FAO WATER Irrigation in Southern REPORTS and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 37 Edited by Karen FRENKEN FAO Land and Water Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2012 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107282-0 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy.