Mountains of Asia a Regional Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

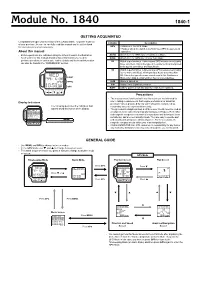

Module No. 1840 1840-1

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Leonetti-Geo3.Pdf

GEO 3 Il Mondo: i paesaggi, la popolazione e l'economia 3 media:-testo di Geografia C3 pag. 2 Geo 3: Il Mondo I paesaggi, la popolazione, l’economia Per la Scuola Secondaria di Primo Grado a cura di Elisabetta Leonetti Coordinamento editoriale: Antonio Bernardo Ricerca iconografica: Cristina Capone Cartine tematiche: Studio Aguilar Copertina Ginger Lab - www.gingerlab.it Settembre 2013 ISBN 9788896354513 Progetto Educationalab Mobility IT srl Questo libro è rilasciato con licenza Creative Commons BY-SA Attribuzione – Non commerciale - Condividi allo stesso modo 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/legalcode Alcuni testi di questo libro sono in parte tratti da Wikipedia Versione del 11/11/2013 Modificato da [email protected] – 23/9/15 INDICE GEO 3 Glossario Mappe-Carte AulaVirtuale 3 media:-testo di Geografia C3 pag. 3 Presentazione Questo ebook fa parte di una collana di ebook con licenza Creative Commons BY-SA per la scuola. Il titolo Geo C3 vuole indicare che il progetto è stato realizzato in modalità Collaborativa e con licenza Creative Commons, da cui le tre “C” del titolo. Non vuole essere un trattato completo sull’argomento ma una sintesi sulla quale l’insegnante può basare la lezione, indicando poi testi e altre fonti per gli approfondimenti. Lo studente può consultarlo come riferimento essenziale da cui partire per approfondire. In sostanza, l’idea è stata quella di indicare il nocciolo essenziale della disciplina, nocciolo largamente condiviso dagli insegnanti. La licenza Creative Commons, con la quale viene rilasciato, permette non solo di fruire liberamente l’ebook ma anche di modificarlo e personalizzarlo secondo le esigenze dell’insegnante e della classe. -

Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010

LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 MATERIALS / 6 / MATERIALS Col·lecció Materials, 6 Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010 Col·lecció Materials, 6 Primera edició: febrer de 2011 Editat per: Amb el suport de : Coordinació editorial: Josep Cru i Lachman Khubchandani Traduccions a l’anglès: Kari Friedenson i Victoria Pounce Revisió dels textos originals en anglès: Kari Friedenson Revisió dels textos originals en francès: Alain Hidoine Disseny i maquetació: Monflorit Eddicions i Assessoraments, sl. ISBN: 978-84-15057-12-3 Els continguts d’aquesta publicació estan subjectes a una llicència de Reconeixe- ment-No comercial-Compartir 2.5 de Creative Commons. Se’n permet còpia, dis- tribució i comunicació pública sense ús comercial, sempre que se’n citi l’autoria i la distribució de les possibles obres derivades es faci amb una llicència igual a la que regula l’obra original. La llicència completa es pot consultar a: «http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/es/deed.ca» LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 Centre UNESCO de Catalunya Barcelona, 2011 4 CONTENTS PRESENTATION Miquel Àngel Essomba 6 FOREWORD Josep Cru 8 1. THE HISTORY OF LINGUAPAX 1.1 Materials for a history of Linguapax 11 Fèlix Martí 1.2 The beginnings of Linguapax 14 Miquel Siguan 1.3 Les débuts du projet Linguapax et sa mise en place 17 au siège de l’UNESCO Joseph Poth 1.4 FIPLV and Linguapax: A Quasi-autobiographical 23 Account Denis Cunningham 1.5 Defending linguistic and cultural diversity 36 1.5 La defensa de la diversitat lingüística i cultural Fèlix Martí 2. GLIMPSES INTO THE WORLD’S LANGUAGES TODAY 2.1 Living together in a multilingual world. -

Shankar Ias Academy Test 18 - Geography - Full Test - Answer Key

SHANKAR IAS ACADEMY TEST 18 - GEOGRAPHY - FULL TEST - ANSWER KEY 1. Ans (a) Explanation: Soil found in Tropical deciduous forest rich in nutrients. 2. Ans (b) Explanation: Sea breeze is caused due to the heating of land and it occurs in the day time 3. Ans (c) Explanation: • Days are hot, and during the hot season, noon temperatures of over 100°F. are quite frequent. When night falls the clear sky which promotes intense heating during the day also causes rapid radiation in the night. Temperatures drop to well below 50°F. and night frosts are not uncommon at this time of the year. This extreme diurnal range of temperature is another characteristic feature of the Sudan type of climate. • The savanna, particularly in Africa, is the home of wild animals. It is known as the ‘big game country. • The leaf and grass-eating animals include the zebra, antelope, giraffe, deer, gazelle, elephant and okapi. • Many are well camouflaged species and their presence amongst the tall greenish-brown grass cannot be easily detected. The giraffe with such a long neck can locate its enemies a great distance away, while the elephant is so huge and strong that few animals will venture to come near it. It is well equipped will tusks and trunk for defence. • The carnivorous animals like the lion, tiger, leopard, hyaena, panther, jaguar, jackal, lynx and puma have powerful jaws and teeth for attacking other animals. 4. Ans (b) Explanation: Rivers of Tamilnadu • The Thamirabarani River (Porunai) is a perennial river that originates from the famous Agastyarkoodam peak of Pothigai hills of the Western Ghats, above Papanasam in the Ambasamudram taluk. -

Edgar Alexander Mearns Papers, Circa 1871-1916, 1934 and Undated

Edgar Alexander Mearns Papers, circa 1871-1916, 1934 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series 1: General Correspondence, 1886-1909, and undated................................. 3 Series 2: Biographical Material, 1879, 1885-1900, 1934......................................... 4 Series 3: Field Notes, Research Notes, Specimen Lists, Manuscripts, and Reprints, 1871-1911, and undated.......................................................................................... 5 Series 4: United States-Mexican International Boundary Survey, 1892-1894. Correspondence, Photographs, Drawings, and Research Data on Mammals, circa 1891-1907................................................................................................................ -

Los Cien Montes Más Prominentes Del Planeta D

LOS CIEN MONTES MÁS PROMINENTES DEL PLANETA D. Metzler, E. Jurgalski, J. de Ferranti, A. Maizlish Nº Nombre Alt. Prom. Situación Lat. Long. Collado de referencia Alt. Lat. Long. 1 MOUNT EVEREST 8848 8848 Nepal/Tibet (China) 27°59'18" 86°55'27" 0 2 ACONCAGUA 6962 6962 Argentina -32°39'12" -70°00'39" 0 3 DENALI / MOUNT McKINLEY 6194 6144 Alaska (USA) 63°04'12" -151°00'15" SSW of Rivas (Nicaragua) 50 11°23'03" -85°51'11" 4 KILIMANJARO (KIBO) 5895 5885 Tanzania -3°04'33" 37°21'06" near Suez Canal 10 30°33'21" 32°07'04" 5 COLON/BOLIVAR * 5775 5584 Colombia 10°50'21" -73°41'09" local 191 10°43'51" -72°57'37" 6 MOUNT LOGAN 5959 5250 Yukon (Canada) 60°34'00" -140°24’14“ Mentasta Pass 709 62°55'19" -143°40’08“ 7 PICO DE ORIZABA / CITLALTÉPETL 5636 4922 Mexico 19°01'48" -97°16'15" Champagne Pass 714 60°47'26" -136°25'15" 8 VINSON MASSIF 4892 4892 Antarctica -78°31’32“ -85°37’02“ 0 New Guinea (Indonesia, Irian 9 PUNCAK JAYA / CARSTENSZ PYRAMID 4884 4884 -4°03'48" 137°11'09" 0 Jaya) 10 EL'BRUS 5642 4741 Russia 43°21'12" 42°26'21" West Pakistan 901 26°33'39" 63°39'17" 11 MONT BLANC 4808 4695 France 45°49'57" 06°51'52" near Ozero Kubenskoye 113 60°42'12" c.37°07'46" 12 DAMAVAND 5610 4667 Iran 35°57'18" 52°06'36" South of Kaukasus 943 42°01'27" 43°29'54" 13 KLYUCHEVSKAYA 4750 4649 Kamchatka (Russia) 56°03'15" 160°38'27" 101 60°23'27" 163°53'09" 14 NANGA PARBAT 8125 4608 Pakistan 35°14'21" 74°35'27" Zoji La 3517 34°16'39" 75°28'16" 15 MAUNA KEA 4205 4205 Hawaii (USA) 19°49'14" -155°28’05“ 0 16 JENGISH CHOKUSU 7435 4144 Kyrghysztan/China 42°02'15" 80°07'30" -

Reisverslag Georgië

REISVERSLAG Bestemming LAND: GEORGIE STREEK/STAD: Tblisi – Signagi – Kazbegi (Stepantsminda) –Vardzia – Gori TRAJECT: Brugge – Brussel – Istanbul – Tblisi – Signagi – Kazbegi – Vardzia – Gori – Tblisi – Istanbul – Brussel – Brugge Periode van 27/09/2019 tot 05/10/2019 Was je daar reeds voorheen? X nee Reisgezelschap X Alleen O met partner O met vriend Aard van de Reis X Individueel O Georganiseerd (er wordt beroep gedaan op een reisorganisator voor vervoer en logies): Wat boekte je precies bij je reisagent? X transport O logies O rondreis Logies werden allemaal via Internet gereserveerd (booking.com). Autohuur werd via de website van de verhuurmaatschappij GSServices geboekt. Wat was: - het reisbureau: Kilroy online. - de vervoersmaatschappij (trein, bus, vliegtuig,...): Turkish Airlines. Wat is je oordeel erover? Zie bijgaand verslag. Transport Welk transportmiddel gebruikte je en wat kostte dat? - heen en terug naar Georgië: vliegtuig met Turkish Airlines van Brussel naar Tblisi en terug (de verbinding verliep via Istanbul): 316 € (taks inclusief), geen dossierkosten, noch kosten voor gebruik Mastercard. Annulatieverzekering werd niet genomen, ik beschik over een VAB jaarpolis. - Het vliegtuigticket werd gekozen in functie van vlotte verbindingen, vluchtduur en goede vertrek- en aankomsttijden. Op die manier was het ticket duurder (+80 euro) dan bijvoorbeeld met Pegasus waar je een nacht in Istanbul vast zat. - ter plaatse in Georgië: huurauto 6 dagen (SUV 4x4, Toyota Rav4) 1029 GEL (= 320 euro) vanaf Tblisi centrum bij GSServices (online via mail geboekt), alle verzekeringen inclusief. Borg bij ophaling bedraagt 200 US$. GEO10 – Ivan Verschoote 1/25 © Copyright bij de auteur. Dit reisverslag wordt u aangeboden door Wegwijzer Reisinfo vzw. De auto werd door hen aan mijn hotel in Tblisi gebracht en na 6 dagen daar terug afgehaald zonder meerkost. -

The Spatial Differentiation of the Suitability of Ice-Snow Tourist Destinations Based on a Comprehensive Evaluation Model in China

sustainability Article The Spatial Differentiation of the Suitability of Ice-Snow Tourist Destinations Based on a Comprehensive Evaluation Model in China Jun Yang 1,*, Ruimeng Yang 1, Jing Sun 1, Tai Huang 2,3,* and Quansheng Ge 3 1 Liaoning Key Laboratory of Physical Geography and Geomatics, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian 116029, China; [email protected] (R.Y.); [email protected] (J.S.) 2 Department of Tourism Management, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, China 3 Key Laboratory of Land Surface Patterns and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (T.H.) Academic Editors: Jun Liu, Gang Liu and This Rutishauser Received: 1 February 2017; Accepted: 4 May 2017; Published: 8 May 2017 Abstract: Ice, snow, and rime are wonders of the cold season in an alpine climate zone and climate landscape. With its pure, spectacular, and magical features, these regions attract numerous tourists. Ice and snow landscapes can provide not only visually-stimulating experiences for people, but also opportunities for outdoor play and movement. In China, ice and snow tourism is a new type of recreation; however, the establishment of snow and ice in relation to the suitability of the surrounding has not been clearly expressed. Based on multi-source data, such as tourism, weather, and traffic data, this paper employs the Delphi-analytic hierarchy process (AHP) evaluation method and a spatial analysis method to study the spatial differences of snow and ice tourism suitability in China. China’s ice and snow tourism is located in the latitude from 35◦N to 53.33◦N and latitude 41.5◦N to 45◦N and longitude 82◦E to 90◦E, with the main focus on latitude and terrain factors. -

Supplement of a Systematic Examination of the Relationships Between CDOM and DOC in Inland Waters in China

Supplement of Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 5127–5141, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-5127-2017-supplement © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Supplement of A systematic examination of the relationships between CDOM and DOC in inland waters in China Kaishan Song et al. Correspondence to: Kaishan Song ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 3.0 License. Figure S1. Sampling location at three rivers for tracing the temporal variation of CDOM and DOC. The average widths at sampling stations are about 1020 m, 206m and 152 m for the Songhua River, Hunjiang River and Yalu River, respectively. Table S1 the sampling information for fresh and saline water lakes, the location information shows the central positions of the lakes. Res. is the abbreviation for reservoir; N, numbers of samples collected; Lat., latitude; Long., longitude; A, area; L, maximum length in kilometer; W, maximum width in kilometer. Water body type Sampling date N Lat. Long. A(km2) L (km) W (km) Fresh water lake Shitoukou Res. 2009.08.28 10 43.9319 125.7472 59 17 6 Songhua Lake 2015.04.29 8 43.6146 126.9492 185 55 6 Erlong Lake 2011.06.24 6 43.1785 124.8264 98 29 8 Xinlicheng Res. 2011.06.13 7 43.6300 125.3400 43 22 6 Yueliang Lake 2011.09.01 6 45.7250 123.8667 116 15 15 Nierji Res. 2015.09.16 8 48.6073 124.5693 436 83 26 Shankou Res. -

1. Linguistics

Topical Report 1. Linguistics MILTON E. BARKER Received I6 April I962 The linguistic sessions of the Tenth Pacific Science Congress, held in Honolulu from 21 August to 6 September 1961, were well attended; and those present report an increased interest in the field of linguistics. The following resolutions were approved and adopted at the closing Plenary Session of the Congress: Current research on Austronesian and Papuan languages is inadequate for scientific needs, and some of them face imminent extinction unless prompt action is taken. Though estimates place the number of languages in the area close to a thousand, ap proximately a fourth or a fifth of the total for the entire world, only a few of the world's small group of linguists have worked in the Oceanic area. As prehistoric population movements in Oceania have been a major interest of this Congress, and as linguistic information constitutes a principal line of evidence toward the reconstruction of po pulation movements, large-scale expansion of bothdescriptive and comparativelinguistic studies is essential to the efficient exploitation of linguistic evidence. RESOLVED that all possible steps be taken to expand research on Pacific languages. Further linguistic surveys in Southeast Asia are needed. RESOLVED that every possible assistance and encouragement be given to institutions of the new nations of Southeast Asia wishing to make linguistic surveys of their peoples. A number of linguists interested in the languages of the Pacific Islands and neighbouring areas held a series of discussions at the Tenth Pacific Science Con gress how to keep themselves informed of each other's work and finally decided to produce a bibliographical publication to be called Oceanic Linguistics whose primary purpose is to provide up-to-date information on research in progress, recently completed, or recently published anywhere in the world. -

North and Central Asia FAO-Unesco Soil Tnap of the World 1 : 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia FAO - Unesco Soil Map of the World

FAO-Unesco S oilmap of the 'world 1:5 000 000 Volume VII North and Central Asia FAO-Unesco Soil tnap of the world 1 : 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia FAO - Unesco Soil map of the world Volume I Legend Volume II North America Volume III Mexico and Central America Volume IV South America Volume V Europe Volume VI Africa Volume VII South Asia Volume VIIINorth and Central Asia Volume IX Southeast Asia Volume X Australasia FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION FAO-Unesco Soilmap of the world 1: 5 000 000 Volume VIII North and Central Asia Prepared by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Unesco-Paris 1978 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not irnply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations or of the United Nations Educa- tional, Scientific and Cultural Organization con- cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delirnitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Printed by Tipolitografia F. Failli, Rome, for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Published in 1978 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris C) FAO/Unesco 1978 ISBN 92-3-101345-9 Printed in Italy PREFACE The project for a joint FAO/Unesco Soil Map of vested with the responsibility of compiling the techni- the World was undertaken following a recommenda- cal information, correlating the studies and drafting tion of the International Society of Soil Science. -

Thirteen Nations on Mount Everest John Cleare 9

Thirteen nations on Mount Everest John Cleare In Nepal the 1971 pre-monsoon season was notable perhaps for two things, first for the worst weather for some seventy years, and second for the failure of an attempt to realise a long-cherished dream-a Cordee internationale on the top of the world. But was it a complete failure? That the much publicised International Himalayan Expedition failed in its climbing objectives is fact, but despite the ill-informed pronouncements of the headline devouring sceptics, safe in their arm-chairs, those of us who were actually members of the expedition have no doubt that internationally we did not fail. The project has a long history, and my first knowledge of it was on a wet winter's night in 1967 at Rusty Baillie's tiny cottage in the Highlands when John Amatt explained to me the preliminary plans for an international expedi tion. This was initially an Anglo-American-Norwegian effort, but as time went by other climbers came and went and various objectives were considered and rejected. Things started to crystallise when Jimmy Roberts was invited to lead the still-embryo expedition, and it was finally decided that the target should be the great South-west face of Mount Everest. However, unaware of this scheme, Norman Dyhrenfurth, leader of the successful American Everest expedition of 1963-film-maker and veteran Himalayan climber-was also planning an international expedition, and he had actually applied for per mission to attempt the South-west face in November 1967, some time before the final target of the other party had even been decided.