Thirteen Nations on Mount Everest John Cleare 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLACIERS of NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range

Glaciers of Asia— GLACIERS OF NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range By Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, JR., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–F–6 CONTENTS Glaciers of Nepal — Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range, by Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi ----------------------------------------------------------293 Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------293 Use of Landsat Images in Glacier Studies ----------------------------------293 Figure 1. Map showing location of the Nepal Himalaya and Karokoram Range in Southern Asia--------------------------------------------------------- 294 Figure 2. Map showing glacier distribution of the Nepal Himalaya and its surrounding regions --------------------------------------------------------- 295 Figure 3. Map showing glacier distribution of the Karakoram Range ------------- 296 A Brief History of Glacier Investigations -----------------------------------297 Procedures for Mapping Glacier Distribution from Landsat Images ---------298 Figure 4. Index map of the glaciers of Nepal showing coverage by Landsat 1, 2, and 3 MSS images ---------------------------------------------- 299 Figure 5. Index map of the glaciers of the Karakoram Range showing coverage -

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

Review: KE007 a Conspiracy of Circumstance, by Murray Sayle

Review: KE007 A Conspiracy of Circumstance, By Murray Sayle The New York Review of Books // April 25, 1985 Black Box: KAL 007 and the Superpowers, by Alexander Dallin // University of California Press, 130 pp., $7.95 (paper) KAL Flight 007: The Hidden Story, by Oliver Clubb // Permanent Press, 174 pp., $16.95 Final Report of Investigation as Required in the Council Resolution of September 16, 1983 [C-WP/7764] International Civil Aviation Organization (Montreal), 113, restricted, but available on serious request pp. 1818th Report to Council by the President of the Air Navigation Commission [C-WP/7809] International Civil Aviation Organization (Montreal), 23, restricted, but available on serious request pp. North Atlantic Airspace Operations Manual-Fourth Edition Civil Aviation Authority (London), 32, available on request pp. NOPAC Route Systems Operations Handbook Administration Anchorage Air Route Traffic Control Center, Federal Aviation, 16, available on request pp. 1. Shortly before dawn on September 1, 1983, a Boeing 747 Flight KE007 of Korean Air Lines was shot down over Sakhalin Island in the Soviet Far East by an SU-15 fighter of the Soviet Air Force, with the loss of all 269 passengers and crew on board. The incident set off a contest in vituperation between the super-powers, which, a year and a half later, still reverberates. President Reagan called the shoot-down "a terrorist act to sacrifice the lives of innocent human beings," while the Soviets have never ceased charging that the aircraft was engaged on a "special mission" of electronic espionage on behalf of the United States, thus by implication justifying what they call their "termination" of the flight. -

Everest Base Camp Challenge Trip

everest base camp Sub‑continent Himalaya Indian challenge trip highligh ts Experience the stunning views of Mount Everest, a truly once in a lifetime opportunity! Test yourself in one of the world’s most challenging regions and raise money for a great cause Discover the hopsitable and proud culture of our local Sherpa guides Enjoy spectacular surroundings and wild views from Namche Bazaar Witness the tranquil surroundings of the Thyangboche Monastery Fully supported camping based trek in private eco campsites Enjoy three hearty meals every day prepared by our cooks Climb Kala Pattar & visit Everest Base Camp Himalayan Mountain flight from Kathmandu to Lukla Sightseeing in Kathmandu ‑ Pashupatinath (a major Hindu shrine) and the giant Buddhist stupa at Boudhanath Trip Duration 18 days Trip Code: SOG3690 Grade Moderate Activities Trekking Summary 18 day Challenge, 14 day trek, 3 nights hotels, 11 nights private eco campsites and 3 nights eco lodge welcome to why travel with World Expeditions? World Expeditions have been pioneering treks in Nepal since 1975. World Expeditions Our extra attention to detail and seamless operations on the ground Thank you for your interest in our Everest Base Camp Challenge trip. ensure that you will have a memorable trekking experience. Every At World Expeditions we are passionate about our off the beaten trek is accompanied by an experienced local leader trained in remote track experiences as they provide our travellers with the thrill of wilderness first aid, as well as knowledgeable crew that share a passion coming face to face with untouched cultures as well as wilderness for the region in which they work, and a desire to share it with you. -

Everest Book Three the Summit

364910_FM_v1_. 10/13/11 10:44 PM Page iii GORDON KORMAN EVEREST BOOK THREE THE SUMMIT SCHOLASTIC INC. New York Toronto London Auckland Sydney Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong 364910_FM_v2_. 11/2/11 11:25 PM Page iv For Daisy Samantha Korman My Summit If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any pay- ment for this “stripped book.” No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. ISBN 978-0-545-39234-1 Copyright © 2002 by Gordon Korman. All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc. SCHOLASTIC and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 12 13 14 15 16 17/0 Printed in the U.S.A. 40 This edition first printing, March 2012 364910_Text_v1.qxd_. 10/13/11 10:41 PM Page 1 PROLOGUE The wind pounced on them above twenty-five thousand feet. As the youngest expedition in Everest history scrambled up the Geneva Spur, the onslaught be- gan — overpowering, unpredictable gusts that threatened to pluck the climbers off the mountain and hurl them into space. Amazingly, this was nothing new to them. -

Dream Merchants

DREAM MERCHANTS I N V E S T I G A T I N G T H E M Y S T E R I O U S D E A T H S O F T H R E E J A P A N E S E C L I M B E R S ON DENALI IN 1989 BY JON WATERMAN Kahiltna Pass, 10,000 feet, lower left with trail to 11,200-foot camp and up West Buttress; Denali Pass visible upper left. TOM FALLEY 22 ASCENT 2020 ASCENT 2020 23 This photograph and another shot from the The 17-man rescue team hauls the bodies of air show that none of the deceased climbers Yamada, Saegusa and Komatsu to a waiting helicopter. Cyclonic winds delayed the body recovery held their knees or burrowed or assumed for over a month. The three climbers were found just the fetal position of those trying to shelter 15 minutes from their last camp. from the extreme cold. Nor had they begun removing their clothing in the frequent final act of “paradoxical undressing” by translated), were weirdly incomplete. It was hypothermic victims flushed by dilated blood as if Yamada’s deferential Japanese supporters vessels that cause a burning sensation. could not dig up or divulge how the men really From my experience as a Denali perished. WHEN NORBORU YAMADA and his two mountaineering ranger performing scores of Several accounts of successful winter Japanese companions didn’t return from searches for climbers, rescues or recoveries— climbs on Denali serve as noteworthy and theW West Buttress, Denali’s easiest route, in along with a study of accident victims for even inspirational models, such as the book February 1989, no one could understand my book Surviving Denali—I wanted Minus 148 (detailing how three climbers what had happened. -

Jim's 1985 Book Reviews Debunk the Conspiracies

An abridged version of the following review appeared in ‘The American Spectator’, October 1985, pp 36-39. The second review is from ’National Review’ magazine, March 27, 1987. Sense, Nonsense, and Pretense on the Korean Airliner Atrocitv -- A Reader's Guide to the Literature, by James E. Oberg // date: July 31, 1985 "Reassessing the Sakhalin incident“, P. Q. Mann (pseudonym). Defence Attache, No. 3. (May-June) 1984, pp 41-56. "K.A.L. 007: What the U.S. Knew and When We Knew It", David Pearson. The Nation, Aug 18-25, 1984, pp 105-124. "Sakhalin Sense and Nonsense", J. E. Oberg, Defence Attache, No. 1 (Jan-Feb) 1985. pp 37-47. KAL FLIGHT 007: The Hidden Story, by Oliver Clubb, Permanent Press, Sag Harbor, New York, April 1965, 174 pages, $16.95. Black Box: KAL 007 and the Superpowers. by Alexander Dallin. University of California Press, Berkeley. California. 1985, 130 pages, $14.95. Day of the Cobra The True Story of KAL Flight 007, by Jeffrey St. John, Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville, Tennessee, 1984, 254 pages, $11.95. Massacre 747: The Story of Korean Airlines Flight 007, by Richard Rohmer, Paperjacks Ltd., Markham, Ontario. May 1964, 213 pages paperback, $3.95. The Curious Flight, of KAL 007, by Conn Hallinan, U. S. Peace Council, New York, NY, 1984, 6 pages. The President's Crime: The Provocation with the South Korean Airliner Carried Out by Order of Reagan, by "Akio Takahashi", Novosti Publishers,Moscow, 1984, 126 pages, 30 kopecks. "KE007 -- A Conspiracy of Circumstance", Murray Sayle, The New York Review of Books, April 25, 1965, pages 44-54. -

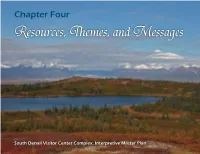

Chapter Four

Chapter Four South Denali Visitor Center Complex: Interpretive Master Plan Site Resources Tangible Natural Site Features 1. Granite outcroppings and erratic Resources are at the core of an boulders (glacial striations) interpretive experience. Tangible resources, those things that can be seen 2. Panoramic views of surrounding or touched, are important for connecting landscape visitors physically to a unique site. • Peaks of the Alaska Range Intangible resources, such as concepts, (include Denali/Mt. McKinley, values, and events, facilitate emotional Mt. Foraker, Mt. Hunter, Mt. and meaningful experiences for visitors. Huntington, Mt. Dickey, Moose’s Effective interpretation occurs when Erratic boulders on Curry Ridge. September, 2007 Tooth, Broken Tooth, Tokosha tangible resources are connected with Mountains) intangible meanings. • Peters Hills • Talkeetna Mountains The visitor center site on Curry Ridge maximizes access to resources that serve • Braided Chulitna River and valley as tangible connections to the natural and • Ruth Glacier cultural history of the region. • Curry Ridge The stunning views from the visitor center site reveal a plethora of tangible Mt. McKinley/Denali features that can be interpreted. This Mt. Foraker Mt. Hunter Moose’s Tooth shot from Google Earth shows some of the major ones. Tokosha Ruth Glacier Mountains Chulitna River Parks Highway Page 22 3. Diversity of habitats and uniquely 5. Unfettered views of the open sky adapted vegetation • Aurora Borealis/Northern Lights • Lake 1787 (alpine lake) • Storms, clouds, and other weather • Alpine Tundra (specially adapted patterns plants, stunted trees) • Sun halos and sun dogs • High Brush (scrub/shrub) • Spruce Forests • Numerous beaver ponds and streams Tangible Cultural Site Features • Sedge meadows and muskegs 1. -

Everest – South Col Route – 8848M the Highest Mountain in the World South Col Route from Nepal

Everest – South Col Route – 8848m The highest mountain in the world South Col Route from Nepal EXPEDITION OVERVIEW Join Adventure Peaks on their twelfth Mt Everest Expedition to the world’s highest mountain at 8848m (29,035ft). Our experience is amongst the best in the world, combined with a very high success rate. An ultimate objective in many climbers’ minds, the allure of the world’s highest summit provides a most compelling and challenging adventure. Where there is a will, we aim to provide a way. Director of Adventure Peaks Dave Pritt, an Everest summiteer, has a decade of experience on Everest and he is supported by Stu Peacock, a regular and very talented high altitude mountaineer who has led successful expeditions to both sides of Everest as well as becoming the first Britt to summit Everest three times on the North Side. The expedition is a professionally-led, non-guided expedition. We say non-guided because our leader and Sherpa team working with you will not be able to protect your every move and you must therefore be prepared to move between camps unsupervised. You will have an experienced leader who has previous experience of climbing at extreme high altitude together with the support of our very experienced Sherpa team, thus increasing your chance of success. Participation Statement Adventure Peaks recognises that climbing, hill walking and mountaineering are activities with a danger of personal injury or death. Participants in these activities should be aware of and accept these risks and be responsible for their own actions and involvement. Adventure Travel – Accuracy of Itinerary Although it is our intention to operate this itinerary as printed, it may be necessary to make some changes as a result of flight schedules, climatic conditions, limitations of infrastructure or other operational factors. -

Threading the Needle Skiing Lhotse's Dream Line

AAC Publications Threading the Needle Skiing Lhotse's Dream Line ON SEPTEMBER 30, at about 2 p.m., Jim Morrison and I pulled off our overboots, clicked into our ski bindings, and laboriously buckled our boots. Our oxygen masks were off, making every action at 27,940 feet, on the summit of Lhotse, extremely slow and difficult. I reached for my backpack, so much lighter now that my skis were on my feet, and swung it over my right shoulder, then slowly buckled the waist and chest straps. I slid my oxygen mask back over my face, stuck my right hand on the summit cornice, and soaked up the view one last time. Exactly four weeks earlier, on August 31, our team of four—Jim and I, along with photographers Dutch Simpson and Nick Kalisz—left the U.S. from various points and convened at the Kathmandu airport. Jim and I went straight from the hotel to the Nepal Ministry of Tourism to register for our expedition, pay garbage fees, meet our liaison officer, and finalize the two necessary permits for Lhotse: one for climbing and one for skiing back down. We took another full day to organize in Kathmandu before heading to the airport to fly into the Khumbu and begin our trek to base camp. Our goal for this expedition was simple: Jim and I wanted to ski the Lhotse Couloir from the summit in as pure a fashion as we could muster. Forming a super-direct narrow line from the upper Lhotse Face to the summit, the couloir was a dream line for skiing and the complete descent had been attempted several times. -

EVEREST – Film at CONCA VERDE on 11.01.16 – Talk by Peter Anderson (From Wikipedia)

EVEREST – Film at CONCA VERDE on 11.01.16 – Talk by Peter Anderson (from Wikipedia) Everest is a 2015 survival film directed by Baltasar Kormákur and written by William Nicholson and Simon Beaufoy. The film stars are Jason Clarke, Josh Brolin, John Hawkes, Robin Wright, Michael Kelly, Sam Worthington, Keira Knightley, Emily Watson, and Jake Gyllenhaal. The film opened the 72nd Venice International Film Festival on September 2, 2015, and was released theatrically on September 18, 2015. It is based on the real events of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, and focuses on the survival attempts of two expedition groups, one led by Rob Hall (Jason Clarke) and the other by Scott Fischer (Jake Gyllenhaal). Survival films The survival film is a film genre in which one or more characters make an effort at physical survival. It often overlaps with other film genres. It is a subgenre of the adventure film, along with swashbuckler films (film di cappa e spada – like Zorro or Robin Hood), war films, and safari films. Survival films are darker than most other adventure films which usually focuses its storyline on a single character, usually the protagonist. The films tend to be "located primarily in a contemporary context" so film audiences are familiar with the setting, meaning the characters' activities are less romanticized. Thomas Sobchack compared the survival film to romance: "They both emphasize the heroic triumph over obstacles which threaten social order and the reaffirmation of predominant social values such as fair play and respect for merit and cooperation." [2] The author said survival films "identify and isolate a microcosm of society", such as the surviving group from the plane crash in The Flight of the Phoenix (1965) or those on the overturned ocean liner in The Poseidon Adventure (1972). -

Sheryl Falk: a Data Privacy Lawyer & Mount Everest Climber

Free Speech, Due Process and Trial by Jury Sheryl Falk: A Data Privacy Lawyer & Mount Everest Climber Sheryl Falk at a memorial to perished Everest climbers By Natalie Posgate (Jan. 25) – It’s not very often that Sheryl Falk gets to slow Winston’s firmwide mentoring program targeted at down, turn off her phone and think in-depth about her helping young associates. She also informally mentors life. As co-leader of Winston & Strawn’s global privacy several associates at the firm. and data security task force, the Houston partner is always on the go – traveling almost every week, She was inspired to open this new chapter in her career speaking at various conferences and ending her nights while trekking in the shadow of Mount Pumori, which staying abreast of all her work emails. lies eight kilometers west of Mount Everest. Named after the daughter of George Mallory, the famed British But Falk recently had an off-the-grid opportunity when mountaineer who was a leading member of the first she traded two-and-a-half weeks of billable hours for few expeditions of Mount Everest, Pumori means her No. 1 bucket list item: making the climb to Everest “Mountain Daughter” in the Sherpa language. Base Camp. “The mountains are so tall and glorious that you’re Falk returned from the trek not only fulfilling a lifelong literally trekking in the shadow of giants,” Falk told The dream but also with a new career goal: help advance Texas Lawbook. more younger women attorneys. “As I was trekking I was just in gratitude – I’m living the Falk is now part of the faculty of the University of life of my dreams, I’ve accomplished everything I’ve Texas’s 2019 Women in Law Institute, a full-day wanted.