RE:MARKS from EAST TIMOR: a Field Guide to East Timor’S Graffiti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Development and Economic Transition Under International Governance: the Case of East Timor

Revised August 22 2000 National development and economic transition under international governance: the case of East Timor Jorge Braga de Macedo Institute of Tropical Research and Nova University at Lisbon José Braz TEcFinance Ltd, Lisbon Rui Sousa Monteiro Nova University at Lisbon Introduction East Timor evolved as a nation over several centuries, with a strong spiritual identity making up for colonial neglect. The occupation by neighboring Indonesia also contributed to solidify the national identity of East Timor. In their intervention over the past year, international agencies have been slow in recognizing that this is an asset for the democratic governance of the new state that is unique in post-conflict situations. Ignoring this initial condition of national development can have adverse consequences for the choice of an economic transition path. In the current international governance setup, military intervention may already have been excessive relative to the empowerment of the CNRT (National Council for Timorese Resistance). The consequence was a waste of time and financial resources. The fact that East Timor already existed as a nation obviates the need for the manifestations of economic nationalism usually present in recently constituted nation- states. In their strategy for national development, democratically elected authorities can avoid the temptation to create an autonomous currency, to nationalize significant economic sectors or to implement other protectionist measures. Such a national development strategy has direct implications on fiscal policy. Without a need to finance heavy government intervention in economic life, tax design can be guided by principles of simplicity and have relatively low rates. Rather than relying on a complex progressive personal and corporate tax collection system, the royalties from oil and gas exploration can then perform the distributive functions. -

Catalogue of the Exhibition

Cover Image: Clive Hyde, The Eyes Have It, 1982; ‘Lindy Chamberlian is driven away in a prison vehicle after the guilty verdict at the Northern Territory Supreme Court, 1982’ INTRODUCTION The ‘Top End’ is a broad canvas, stretching across based Frédéric Mit interpret the ‘Top End’ quite the NT, WA and Qld and, depending on your literally through their iPhone ‘snaps’ comparing a vantage point, also inclusive of Australia’s northern year of skies in both cities, while award-winning neighbours: East Timor, Indonesia and Papua New photographer/writer Andrew Quilty’s Cyclone Guinea, for example. Onto this broad canvas lies Yasi Aftermath investigates the fallout from more a myriad of lives and landscapes, layers of history menacing skies in the cyclone-prone tropics. and drama both epic and everyday. How we see or understand this region and its people is largely the challenge of the photojournalist, charged with From Megan Lewis’s award-winning Conversations capturing the sense of a real-life character or event with the Mob series/publication, portraying Martu Exhibited at Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA) and Darwin Waterfront, May/June 2014 through the lens of their camera and their readiness life in the Great Sandy Desert, to Martine Perret’s Curated by Maurice O’Riordan, Crystal Thomas & Glenn Campbell to put themselves ‘there’. acclaimed Trans Dili series focusing on transgender life in East Timor, to Ed Wray’s disturbing Monkey NCCA, 3 May to 1 June 2014 Town exposé of a street performing monkey in Glenn Campbell, Brian Cassey, -

![GEOGRAPHY)] Born with the Vision of “Enabling a Person Located at the Most Remote Destination a Chance at Cracking AIR 1 in IAS”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8566/geography-born-with-the-vision-of-enabling-a-person-located-at-the-most-remote-destination-a-chance-at-cracking-air-1-in-ias-1088566.webp)

GEOGRAPHY)] Born with the Vision of “Enabling a Person Located at the Most Remote Destination a Chance at Cracking AIR 1 in IAS”

IASBABA.COM 2018 IASBABA [IASBABA’S 60 DAYS PLAN-COMPILATION (GEOGRAPHY)] Born with the vision of “Enabling a person located at the most remote destination a chance at cracking AIR 1 in IAS”. IASbaba’s 60 Days Plan – (Geography Compilation) 2018 Q.1) Consider the following. 1. Himalayas 2. Peninsular Plateau 3. North Indian Plains Arrange the following in chronological order of their formations. a) 1-3-2 b) 2-1-3 c) 2-3-1 d) 3-2-1 Q.1) Solution (b) The oldest landmass, (the Peninsula part), was a part of the Gondwana land. The Gondwana land included India, Australia, South Africa, South America and Antarctica as one single land mass. The northward drift of Peninsular India resulted in the collision of the plate with the much larger Eurasian Plate. Due to this collision, the sedimentary rocks which were accumulated in the geosyncline known as the Tethys were folded to form the mountain system of western Asia and Himalayas. The Himalayan uplift out of the Tethys Sea and subsidence of the northern flank of the peninsular plateau resulted in the formation of a large basin. In due course of time this depression, gradually got filled with deposition of sediments by the rivers flowing from the mountains in the north and the peninsular plateau in the south. A flat land of extensive alluvial deposits led to the formation of the northern plains of India. Do you know? Geologically, the Peninsular Plateau constitutes one of the ancient landmasses on the earth’s surface. It was supposed to be one of the most stable land blocks. -

Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in Figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011

37 Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 FAO WATER Irrigation in Southern REPORTS and Eastern Asia in figures AQUASTAT Survey – 2011 37 Edited by Karen FRENKEN FAO Land and Water Division FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2012 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107282-0 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

Thesis Is Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia

LEADERSHIP AT THE PRIMARY SCHOOL LEVEL IN POST-CONFLICT TIMOR-LESTE: A STUDY OF THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, RECENT DEVELOPMENTS AND CURRENT CONCERNS OF SCHOOL LEADERS Shayla Maria Babo Ribeiro Master of Business Administration Master of Management Bachelor of Science (Cartography) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia Graduate School of Education Faculty of Arts, Business, Law and Education 2019 THESIS DECLARATION I, Shayla Maria Babo Ribeiro, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by The University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval #: RA/4/1/7396. Written patient consent was obtained and archived for the research involving patient data reported in this thesis. -

The Walk on Campus

The Walk on Campus A unique, half-day workshop for educators interested in bringing Paul Salopek’s Out of Eden Walk into the university classroom The Walk on Campus WORKSHOP FOR UNIVERSITY EDUCATORS N PARTNERSHIP WITH THE PULITZER CENTER on Crisis Reporting, the Out of Eden Walk is offering half-day workshops on university campuses designed to share Pulitzer Prize-winner Paul Salopek’s style of “slow” journalism on digital platforms. We invite professors across disciplines to join us, whether in journalism, geography, international studies, anthropology, environmental science, education, or other fields. In this practical, fast-pacedI workshop, journalist Grounded in the Walk’s literature and spirit of and educator Don Belt of the University of Rich- innovation, Belt developed his curriculum at mond shares ideas on using Salopek’s historic, Virginia Commonwealth University and the seven-year, 22,000-mile reportage to teach stu- University of Richmond in close collaboration dents to slow down, carefully observe, and use the with Salopek, who is supported by the Knight digital tools in their hip pockets to tell the subtle, Foundation, the National Geographic Society, powerful stories that “fast” journalists often over- the Pulitzer Center, and others. look in the rush to feed a 24/7 news cycle. The Walk on Campus Workshop draws from Belt’s classroom experience and Salopek’s rich “We were inspired by Paul’s work body of work, including more than 150 dispatches to apply the philosophy of slow and feature articles and ongoing innovations in the use of digital cartography, photography, journalism to covering the streets videography, language translations, sound record- and neighborhoods of our ings, social media, and own city. -

Download Article (PDF)

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 170 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL. SURVEY.... OF -INDIA Geographical distribution .and Zoogeography of Odonata (Insecta). of Meghalaya, India TRIDIB RANJAN MITRA ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 170 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Geographical distribution and Zoogeography of Odonata (Illsecta) of Meghalaya, India TRIDIB RANJAN MITRA Zoological Sitrvey of India, Calcutta Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of Indirz, Calcutta Zoological Survey of India Calcutta 1999 Published: March. 1999 ISBN· 81-85874-11- 5 © Goverllnlent of India, 1999 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in a retrieval system or translnitted, in any form or by any means, ele~tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold hired out or otherwise disposed of wit~out the publisher's consent, in any form of bindi~g or cover other than that in which.it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price i ndicaled by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable PRICE: Rs. 100/· S 6 £4 Published at the Publication Division ~y the Director, Zoological Survey of India, 234/4 AJC Bose Road, 2nd MSO Building (13th Floor), Nizaln Palace, Calcutta-700 020 after laser typesetting by Krishna Printing Works, 106 Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-700 006 and printed by Hooghly Printing Co. Ltd. -

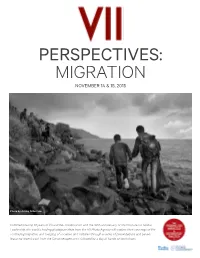

Vii-Migration-Program Copy 3

PERSPECTIVES: MIGRATION NOVEMBER 14 & 15, 2015 Photo by Ashley Gilbertson Commemorating 10 years of VII and IGL collaboration and the 30th anniversary of the Institute for Global Leadership, the world’s leading photojournalists from the VII Photo Agency will explore their coverage of the continuing migration and merging of societies and cultures through a series of presentations and panels featuring recent work from the Syrian refugee crisis followed by a day of hands on workshops. THE AGENDA Saturday, November 14: SEMINARS 1:15 PM: PART ONE – HISTORY: The First Migration Sunday, November 15: Man has been seeking better opportunities since our ancestors’ first migration out WORKSHOPS of Africa. John Stanmeyer is documenting man’s journey and subsequent evolution with National Geographic’s Out of Eden Project – an epic 21,000-mile, 11:00 AM: Street Photography seven year odyssey from Ethiopia to South America. Ed Kashi and Maciek Nabrdalik will 2:00 PM: PART TWO – CRISIS: The European Refugee Crisis lead students around Boston and guide them on how to approach VII photographers are documenting the developing refugee crisis from its origins subjects, compose their frames, and in the Syrian uprising to the beaches of Greece and beyond. Technology has both find new and unexpected angles. An expanded the reach and immediacy of their work while challenging our definition editing critique with the of a true image. photographers will follow the VII Photographers: Ron Haviv, Maciek Nabrdalik, Franco Pagetti and Ashley shooting session. Gilbertson Panelist: Glenn Ruga, Founder of Social Documentary Network and ZEKE 11:00 AM: Survival: The Magazine Complete Travel Toolkit Moderated by Sherman Teichman, Founding Director, Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University Ron Haviv will share tips and tricks on how best to survive and thrive in the 3:30 PM Break before, during, and after of a shoot. -

Networked Governance of Freedom and Tyranny: Peace in Timor-Leste

Networked Governance of Freedom and Tyranny Peace in Timor-Leste Networked Governance of Freedom and Tyranny Peace in Timor-Leste John Braithwaite, Hilary Charlesworth and Adérito Soares Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Braithwaite, John. Title: Networked governance of freedom and tyranny : peace in Timor-Leste / John Braithwaite, Hilary Charlesworth and Adérito Soares. ISBN: 9781921862755 (pbk.) 9781921862762 (ebook) Series: Peacebuilding compared. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Timor-Leste--Politics and government. Timor-Leste--Autonomy and independence movements. Timor-Leste--History. Timor-Leste--Relations--Australia. Australia--Relations--Timor-Leste. Other Authors/Contributors: Charlesworth, H. C. (Hilary C.) Soares, Adérito. Dewey Number: 320.95987 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover photo: Veronica Pereira Maia, Sydney, 1996. ‘I wove this tais and wove in the names of all the victims of the massacre in Dili on 12 November 1991. When it touches my body, I’m overwhelmed with sadness. I remember the way those young people lost their lives for our nation.’ Photo: Ross Bird Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Dedication vii Preface ix Advisory Panel xv Glossary xvii Map xxi 1. A Political Puzzle 1 2. -

Mountains of Asia a Regional Inventory

International Centre for Integrated Asia Pacific Mountain Mountain Development Network Mountains of Asia A Regional Inventory Harka Gurung Copyright © 1999 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development All rights reserved ISBN: 92 9115 936 0 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226 Kathmandu, Nepal Photo Credits Snow in Kabul - Madhukar Rana (top) Transport by mule, Solukhumbu, Nepal - Hilary Lucas (right) Taoist monastry, Sichuan, China - Author (bottom) Banaue terraces, The Philippines - Author (left) The Everest panorama - Hilary Lucas (across cover) All map legends are as per Figure 1 and as below. Mountain Range Mountain Peak River Lake Layout by Sushil Man Joshi Typesetting at ICIMOD Publications' Unit The views and interpretations in this paper are those of the author(s). They are not attributable to the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and do not imply the expression of any opinion concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Preface ountains have impressed and fascinated men by their majesty and mystery. They also constitute the frontier of human occupancy as the home of ethnic minorities. Of all the Mcontinents, it is Asia that has a profusion of stupendous mountain ranges – including their hill extensions. It would be an immense task to grasp and synthesise such a vast physiographic personality. Thus, what this monograph has attempted to produce is a mere prolegomena towards providing an overview of the regional setting along with physical, cultural, and economic aspects. The text is supplemented with regional maps and photographs produced by the author, and with additional photographs contributed by different individuals working in these regions. -

Future Directions for Educational Research Michael Samuel

Opening address at the 2014 SAERA conference Angels in the wind: future directions for educational research Michael Samuel (Chair of the Local Organizing Committee) Stanmeyer, John 2013. ‘Sign’, National Geographic An annual prestigious event in the calendar of professional press photographers, photojournalists and documentary photographers is the World Press Photo Award. This event in 2013 was co-ordinated by the World Press Photo Office in Amsterdam and attracted 98 671 submitted images by 5 754 photographers from 132 countries (http://www.worldpressphoto.org/awards/2014). The independent jury of judges for the 57th annual event selected this photograph above by John Stanmeyer, a USA journalist of the National Geographic as the wining photographic image in the category ‘Contemporary issues’. Stanmeyer had 148 Journal of Education, No. 61, 2015 simply titled his image ‘Sign’. It was accompanied by the explanation of his attempt to capture the challenges facing the would-be migrants alongside the coast of Djibouti (North East Africa). These haunting ‘army of shadows’ (RADAR Worldwide, 2014) reflects groups of prospective migrants who are aiming to make the journey to better life opportunities by crossing over the oceans into the Middle East or beginning the journey into Europe. Coming from the surrounding countries of Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea, this image depicts a new kind of Exodus facing the participants who stand alongside the shores searching for signals on the cellphones, aiming to connect a last call to family and friends back home, aiming to connect with the traffickers who had promised a safe passage (legal or not) into the lands of prospects.