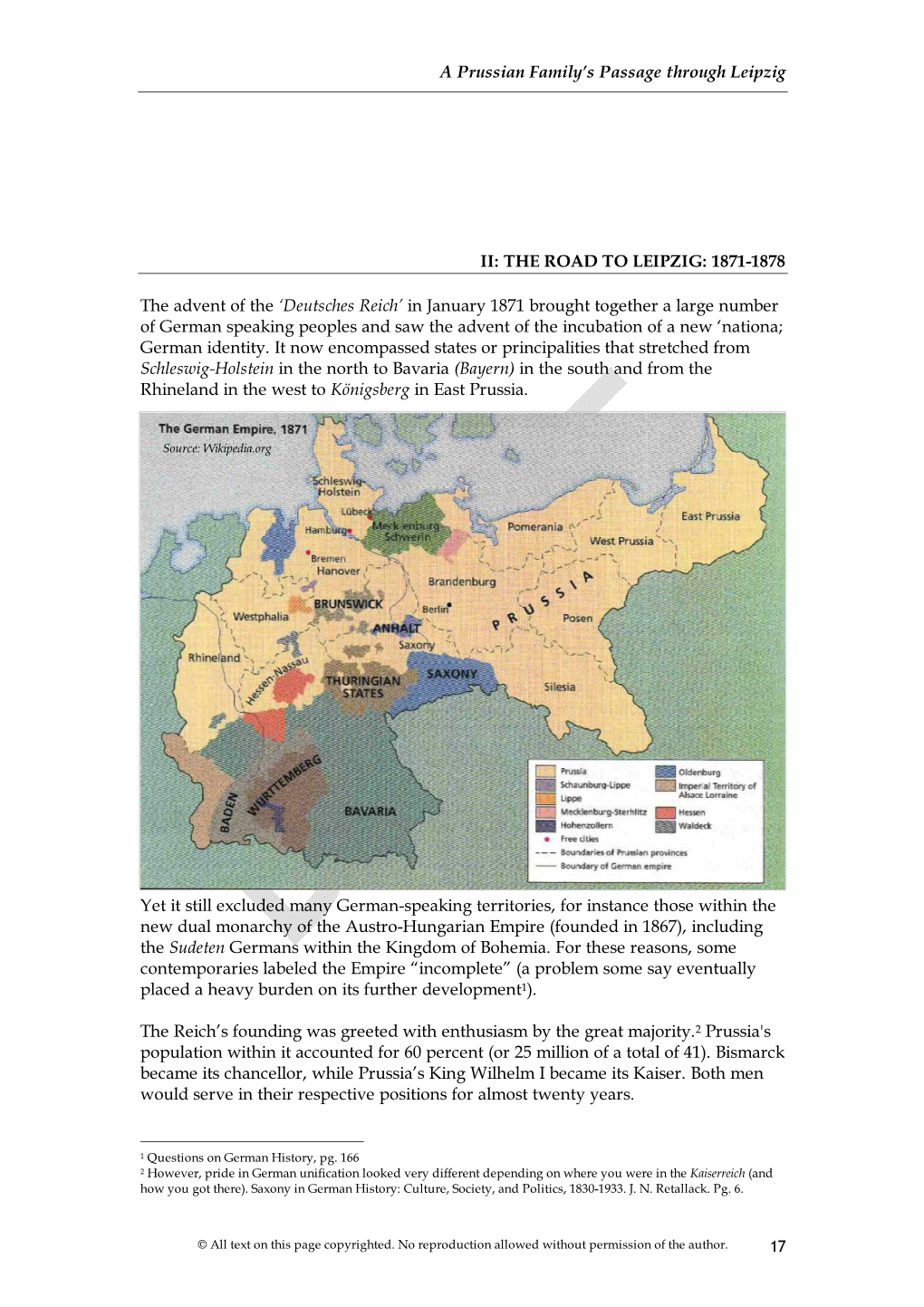

The Road to Leipzig: 1871-1878

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volební Geografie CDU/CSU – Situace Za Vlády Angely Merkelové

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra politologie Obor Politologie Volební geografie CDU/CSU – situace za vlády Angely Merkelové Bakalářská práce Monika Bělašková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Michal Pink, Ph.D. UČO: 397600 Obor: Politologie Imatrikulační ročník: 2011 Brno, 29. 4. 2014 1 Prohlášení o autorství práce Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma Volební geografie CDU/CSU – situace za vlády Angely Merkelové vypracovala samostatně a použila jen zdroje uvedené v seznamu literatury. V Brně, 29. 4. 2014 Podpis:............................................ 2 Poděkování Ráda bych zde poděkovala za užitečné rady a odborné připomínky vedoucímu práce Mgr. Michalu Pinkovi, Ph.D. 3 Anotace Tato práce se zabývá volebními výsledky Křesťansko-demokratické unie a Křesťansko-sociální unie ve Spolkové republice Německo od nástupu Angely Merkelové do kancléřského úřadu. Cílem je zjištění vývoje volební podpory křesťanských stran v průběhu vlády první ženské kancléřky, tedy od r. 2005 do posledních spolkových voleb r. 2013. Práce vychází ze zjišťování volební podpory strany na úrovni volebních obvodů pomocí volební geografie. Závěrečným výstupem je analýza volební podpory strany a nárůstu volebních zisků v průběhu vlády. Annotation This work deals with the election results of the Christian-Democratic Union and Christian-Social Union in the Federal Republic of Germany since Angela Merkel started in the Chanccellor´s Office. Primary aim is detection of the development of electoral support of Christian parties during the government of the first female Chancellor, so from year 2005 until the last Federal votes in the year 2013. The work is based on detection of the election support of the party at the degree of the electoral district using the electoral geography. -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001

ICPSR 2683 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001 Virginia Sapiro W. Philips Shively Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 4th ICPSR Version February 2004 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 www.icpsr.umich.edu Terms of Use Bibliographic Citation: Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Secretariat. COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS, 1996-2001 [Computer file]. 4th ICPSR version. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies [producer], 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2004. Request for Information on To provide funding agencies with essential information about use of Use of ICPSR Resources: archival resources and to facilitate the exchange of information about ICPSR participants' research activities, users of ICPSR data are requested to send to ICPSR bibliographic citations for each completed manuscript or thesis abstract. Visit the ICPSR Web site for more information on submitting citations. Data Disclaimer: The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for uses of this collection or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. Responsible Use In preparing data for public release, ICPSR performs a number of Statement: procedures to ensure that the identity of research subjects cannot be disclosed. Any intentional identification or disclosure of a person or establishment violates the assurances of confidentiality given to the providers of the information. -

14-01 Oberbürgermeisterwahlen 2020

14-01 Oberbürgermeisterwahlen 2020 Oberbürgermeisterwahl Oberbürgermeisterneuwahl Wahlkennziffern / Kandidaten / Parteien am 02.02.2020 am 01.03.2020 absolut Prozent absolut Prozent Wahlberechtigte 469 225 x 469 269 x Wahlbeteiligung 230 201 49,1 227 353 48,4 davon: ungültige Stimmen 815 0,4 1 235 0,5 gültige Stimmen 229 386 99,6 226 118 99,5 davon: Burkhard Jung (SPD) 68 288 29,8 110 965 49,1 Franziska Riekewald (DIE LINKE) 31 038 13,5 nicht angetreten Katharina Krefft (GRÜNE) 27 481 12,0 nicht angetreten Sebastian Gemkow (CDU) 72 430 31,6 107 611 47,6 Christoph Neuman (AfD) 19 854 8,6 nicht angetreten Marcus Viefeld (FDP) 2 739 1,2 nicht angetreten Katharina Subat (Die PARTEI) 5 467 2,4 nicht angetreten Ute Elisabeth Gabelmann (PIRATEN) 2 089 0,9 7 542 3,3 Herr Burkhard Jung (SPD) wurde damit erneut zum Oberbürgermeister der Stadt Leipzig gewählt. Quelle: Amt für Statistik und Wahlen Leipzig Im Ergebnis des ersten Wahlganges vom 02.02 2020 erhielt keiner der Bewerber die erforderliche absolute Mehrheit der abgegebenen gültigen Stimmen. So fand gemäß den Vorschriften des Sächsischen Kommunalwahlgesetzes vier Wochen nach dem ersten Wahltermin eine Neuwahl statt. Statistisches Jahrbuch 2020 (Vorabversion) 14-02 Stadtratswahl 2014 und 2019 Wahl am 25.05.2014 / 12.10.2014 Wahl am 26.05.2019 Wahlkennziffern absolut Prozent Sitze absolut Prozent Sitze Wahlberechtigte 441 513 x x 466 442 x x Wahlbeteiligung 179 941 40,8 x 278 667 59,7 x davon: ungültige Stimmzettel 2 902 1,6 x 3 751 1,3 x gültige Stimmzettel 177 039 98,4 x x Gültige Stimmen -

And Long-Term Electoral Returns to Beneficial

Supporting Information: How Lasting is Voter Gratitude? An Analysis of the Short- and Long-term Electoral Returns to Beneficial Policy Michael M. Bechtel { ETH Zurich Jens Hainmueller { Massachusetts Institute of Technology This version: May 2011 Abstract This documents provides additional information referenced in the main paper. Michael M. Bechtel is Postdoctoral Researcher, ETH Zurich, Center for Comparative and International Studies, Haldeneggsteig 4, IFW C45.2, CH-8092 Zurich. E-mail: [email protected]. Jens Hainmueller is Assistant Professor of Political Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Mas- sachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139. E-mail: [email protected]. I. Potential Alternative Explanation for High Electoral Returns in Affected Regions Some have pointed out that the SPD's victory in 2002 may have simply resulted from Gerhard Schr¨oder(SPD) being much more popular than his political opponent Edmund Stoiber and not from the incumbent's massive and swift policy response to the Elbe flooding. For this argument to be valid we should see a differential reaction to the announcement of Stoiber's candidacy in affected and control regions. We use state-level information on the popularity of chancellor Schr¨oderfrom the Forsa survey data to explore the validity of this argument. Figure 2 plots monthly Schr¨oder'sapproval ratings in affected and unaffected states in 2002. Figure 1: Popularity Ratings of Gerhard Schr¨oderand Flood Onset 60 55 50 45 Schroeder Popularity in % 40 35 2002m1 2002m3 2002m5 2002m7 2002m9 2002m2 2002m4 2002m6 2002m8 Treated states (>10% of districts affected) Controls Election Flood Note: Percent of voters that intend to vote for Gerhard Schr¨oderwith .90 confidence envelopes. -

Assessing the 2009 German Federal Elections: How the SPD's Failure To

Assessing the 2009 German Federal Election: How the SPD’s Failure to Coordinate the Left Put the Right in Power Andrew J. Drummond1 University of Arkansas at Little Rock The recent 2009 German Federal Elections provided a decisive electoral victory for the Christian Democrats, who returned to power without the Social Democrats for the first time in more than a decade. But this shift from grand coalition to center-right cabinet is not the only change in the German electoral landscape─in retrospect, the 2009 election may prove to be a historic turning point in the German party system. The election marked the low water marks in the percentage of list votes won by the CDU and the CSU since the founding democratic election of 1949, when the German party system was in its infancy and party attachments not yet mature. The 2009 election also saw the worst performance in terms of list votes for the SPD since the close of WWII, and the highest percentage of list votes registered by the FDP, the Greens, and die Linke (the former Communists) in German history. In this paper I examine district level returns for clues of how the left is fracturing and what a divided left may mean for the future of German electoral politics. I argue this election may in fact signal a significant and perhaps imminent turning point in partisan attachment on the left that will have wide-ranging implications for the SPD’s electoral and coalition building strategies in the future. Introduction The 2009 general election campaign in Germany was by many accounts a timid affair─some even suggested it was “boring” (Cohen, 2009)2 The Christian Democrats (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands/CDU)─along with their perennial Bavarian partners3, the Christian Socialists (Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern / CSU)─had been locked in a grand coalition with the Social Democrats (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands/SPD) since 2005, and there were 1A previous version of this paper was delivered at the annual meetings of the Arkansas Political Science Association, February 26-27, 2010, Jonesboro, AR. -

Contributions to the Measurement of Public Opinion in Subpopulations

Contributions to the Measurement of Public Opinion in Subpopulations Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Sozialwissenschaen vorgelegt von Simon Munzert an der Sektion Politik – Recht – Wirtscha Fachbereich Politik- und Verwaltungswissenscha Tag der mundlichen¨ Prufung:¨ þÉ. Juli óþÕ¢ Õ. Referent: Prof. Dr. Susumu Shikano, Universitat¨ Konstanz ó. Referent: Prof. Dr. Peter Selb, Universitat¨ Konstanz ì. Referent: Prof. Michael D. Ward, PhD, Duke University Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-296799 To Stefanie Acknowledgments I would not have been able to write and nish this dissertation without the help and support of many people. First of all, I want to thank my collaborators, Peter Selb and Paul Bauer, for their great work and support. eir contributions to the research presented in this thesis are of no small concern. e single papers received manifold and invaluable feedback over the course of their cre- ation. In particular, Peter Selb and I are grateful to Michael Herrmann, omas Hinz, Winfried Pohlmeier, Susumu Shikano as well as the editors and reviewers of Political Analysis for helpful comments and support. is work was also supported by the Center for Quantitative Methods and Survey Research at the University of Konstanz. e second paper that I wrote together with Paul Bauer also got valuable support. We are grateful to Delia Baldassarri for providing materials of her and Andrew Gelman’s analysis to us. We give the raters of the ALLBUS survey items our most sincere thanks for their contribution. Furthermore, we thank Klaus Armingeon, Matthias Fatke, Markus Freitag, Birte Gundelach, Daniel Stegmuller,¨ Richard Traunmuller¨ and Eva Zeglovits for helpful comments on previ- ous versions of this paper. -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES Original CSES file name: cses2_codebook_part3_appendices.txt (Version: Full Release - December 15, 2015) GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Publication (pdf-version, December 2015) ============================================================================================= COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS (CSES) - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS APPENDIX II: PRIMARY ELECTORAL DISTRICTS FULL RELEASE - DECEMBER 15, 2015 VERSION CSES Secretariat www.cses.org =========================================================================== HOW TO CITE THE STUDY: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE [dataset]. December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15 These materials are based on work supported by the American National Science Foundation (www.nsf.gov) under grant numbers SES-0451598 , SES-0817701, and SES-1154687, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, the University of Michigan, in-kind support of participating election studies, the many organizations that sponsor planning meetings and conferences, and the many organizations that fund election studies by CSES collaborators. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. =========================================================================== IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING FULL RELEASES: This dataset and all accompanying documentation is the "Full Release" of CSES Module 3 (2006-2011). Users of the Final Release may wish to monitor the errata for CSES Module 3 on the CSES website, to check for known errors which may impact their analyses. To view errata for CSES Module 3, go to the Data Center on the CSES website, navigate to the CSES Module 3 download page, and click on the Errata link in the gray box to the right of the page. -

City in Focus: Perspectives of the National Urban Development Policy

City in Focus | Perspectives of the National Urban Development Policy Positions of the Policy Board 1 Imprint Publisher Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) within the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (BBR) Deichmanns Aue 31–37 53179 Bonn Scientific Consultants Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) Division I 2: Urban Development Stephan Willinger Contact Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Division SW I 1 Dr. Oliver Weigel Tilman Buchholz Contractors and Authors Team Prof. Dr. Franz Pesch pp a|s pesch partner architekten stadtplaner GmbH and Prof. Peter Zlonicky Office for Urban Planning and Research Editing Elke Wendt-Kummer Holger Everz Translation Michael Cullen, Berlin Layout Doris Fischer-Pesch, Dortmund Status June 2017 Print Domröse druckt, Hagen Orders to: [email protected] Stichwort: Stadt im Fokus Requests for Reprints and Distribution All rights reserved Reprints solely permitted with exact source. Two copies of reprints requested. The ideas of the contractors are not necessarily those of the publisher. ISBN 978-3-87994-206-0 Bonn 2017 City in Focus Perspectives of the National Urban Development Policy Positions of the Policy Board A publication within the framework of the National Urban Development Policy of the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Protection, Construction and Reactor Safety (BMUB), supervised by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Develop- ment (BBSR) within the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (BBR) GREETING This year the National Urban Development Policy in Germany celebrates its 10th anniver- sary. -

And Long-Term Electoral Returns to Beneficial Policy

Supporting Information: How Lasting is Voter Gratitude? An Analysis of the Short- and Long-term Electoral Returns to Beneficial Policy Michael M. Bechtel { ETH Zurich Jens Hainmueller { Massachusetts Institute of Technology This version: May 2011 Abstract This documents provides additional information referenced in the main paper. Michael M. Bechtel is Senior Researcher, ETH Zurich, Center for Comparative and International Studies, IFW C45.2, CH-8092 Zurich. E-mail: [email protected]. Jens Hainmueller is Assistant Professor of Political Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massa- chusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139. E-mail: [email protected]. I. Potential Alternative Explanation for High Electoral Returns in Affected Regions Some have pointed out that the SPD's victory in 2002 may have simply resulted from Gerhard Schr¨oder(SPD) being much more popular than his political opponent Edmund Stoiber and not from the incumbent's massive and swift policy response to the Elbe flooding. For this argument to be valid we should see a differential reaction to the announcement of Stoiber's candidacy in affected and control regions. We use state-level information on the popularity of chancellor Schr¨oderfrom the Forsa survey data to explore the validity of this argument. Figure 2 plots monthly Schr¨oder'sapproval ratings in affected and unaffected states in 2002. Figure 1: Popularity Ratings of Gerhard Schr¨oderand Flood Onset 60 55 50 45 Schroeder Popularity in % 40 35 2002m1 2002m3 2002m5 2002m7 2002m9 2002m2 2002m4 2002m6 2002m8 Treated states (>10% of districts affected) Controls Election Flood Note: Percent of voters that intend to vote for Gerhard Schr¨oderwith .90 confidence envelopes. -

The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand Manuscript Fragment (MS L): New Evidence Concerning Luther, the Poet, and Ottonian Heritage

The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand manuscript fragment (MS L): New evidence concerning Luther, the poet, and Ottonian heritage by Timothy Blaine Price A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Irmengard Rauch, Chair Professor Thomas F. Shannon Professor John Lindow Spring 2010 The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand manuscript fragment (MS L): New evidence concerning Luther, the poet, and Ottonian heritage © 2010 by Timothy Blaine Price Abstract The Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand manuscript fragment (MS L): New evidence concerning Luther, the poet, and Ottonian heritage by Timothy Blaine Price Doctor of Philosophy in German University of California, Berkeley Professor Irmengard Rauch, Chair Begun as an investigation of the linguistic and paleographic evidence on the Old Saxon Leipzig Heliand fragment, the dissertation encompasses three analyses spanning over a millennium of that manuscript’s existence. First, a direct analysis clarifies errors in the published transcription (4.2). The corrections result from digital imaging processes (2.3) which reveal scribal details that are otherwise invisible. A revised phylogenic tree (2.2) places MS L as the oldest extant Heliand document. Further buoying this are transcription corrections for all six Heliand manuscripts (4.1). Altogether, the corrections contrast with the Old High German Tatian’s Monotessaron (3.3), i.e. the poet’s assumed source text (3.1). In fact, digital analysis of MS L reveals a small detail (4.2) not present in the Tatian text, thus calling into question earlier presumptions about the location and timing of the Heliand’s creation (14.4). -

Beschlussempfehlung Und Bericht Des Innenausschusses (4

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 14/5202 14. Wahlperiode 01. 02. 2001 Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Innenausschusses (4. Ausschuss) 1. zu dem Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen SPD und BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN – Drucksache 14/4497 – Entwurf eines Sechzehnten Gesetzes zur Änderung des Bundeswahlgesetzes 2. zu der Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung – Drucksache 14/4031 – Ergänzender Bericht der Wahlkreiskommission für die 14. Wahlperiode des Deutschen Bundestages gemäß § 3 Abs. 4 Satz 3 Bundeswahlgesetz (BWG) A. Problem Aufgrund der Bevölkerungsentwicklung in den Bundesländern sowie in eini- gen Wahlkreisen ist die Einteilung der Wahlkreise für die Wahl zum Deutschen Bundestag gemäß der Anlage zu § 2 Abs. 2 Bundeswahlgesetz (BWG) nicht mehr im Einklang mit den Grundsätzen für die Wahlkreiseinteilung nach § 3 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 2 und 3 BWG. Insbesondere wegen Gebiets- und Verwal- tungsreformen in manchen Ländern, aber auch aufgrund von nach der gelten- den Abgrenzung vereinzelt ohnehin bestehendem Änderungsbedarf, muss die Wahlkreiseinteilung im Hinblick auf die Regelung in § 2 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 5 BWG besser an regionale und kommunale Gebiets- und Verwaltungsstrukturen angepasst werden. Ebenfalls aufgrund der Gebiets- und Verwaltungsreformen in verschiedenen Ländern ist die Beschreibung mehrerer Wahlkreise nicht mehr zutreffend. B. Lösung 1. Durch Änderung der Anlage zu § 2 Abs. 2 BWG werden, soweit erforderlich, Bundestagswahlkreise neu eingeteilt und neu beschrieben. 2. Der ergänzende Bericht der Wahlkreiskommission wird zur Kenntnis genom- men. Drucksache 14/5202 – 2 – Deutscher Bundestag – 14. Wahlperiode Zustimmung zu dem Gesetzentwurf in der Fassung der Ausschussbe- ratung mit den Stimmen der Fraktionen SPD und BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN gegen die Stimmen der Fraktion der CDU/CSU bei Enthaltung der Fraktionen der F.D.P. -

(1876): 153-193

]87'6.] TISCHENDORF. 158 in the lowest depths of history, will not be left to languish for lack of the paltry pittance needed to carry it on. The intelligent piety of our country will assuredly appreciate the work, and see that it wants for not.hing that can make it more abundantly successful. [NOTL - In the citations made from different authora in the preceding Article, the orthography adopted by those authors has been designedly retained, although it differs from the orthography adopted in the main body of the Article. Hence arise the discrepancies which are seen in the method of spelling the proper names.] ARTICLE VII. TISCHENDORF.l BT CA.IIPU uri GRaGORT, LBIPZIG, GB... AIfT. THE life of Tischendorf falls natUrally into two parts, one of preparation, and one of work; though the former shows work enough to have made the name and filled the days of a common man. Let us take a general glance at the years, and then follow the;n in detail. L Preparation: Twenty-nine years + (1815-1844). 1. Fourteen yp,ars + (1815-1829): home. 2. Fourteen years + (1829-1844): student-life. (1.) Seven years + (1829-1886): stndies. (2.) Seven years + (1886-1844) : first publications i 1843, Doctor of Theology. n. Wort: Twenty-nine years + (1844-1878). 1. Fourteen years + (1844-1858): two eastern journeys i finds part of great Codex. Extraordinary and Ordinary Honorary Professor. 2. Fourteen years + (1859-1878): third eastern journey i finds larger part of Codex. Ordinary Professor. Applies the Codex to the text of the New Testament. HIIe year + (1878-1874): fatal illness.